The Duels at Silver Creek

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Seven Forms of Lightsaber Combat Hyper-Reality and the Invention of the Martial Arts Benjamin N

CONTRIBUTOR Benjamin N. Judkins is co-editor of the journal Martial Arts Studies. With Jon Nielson he is co-author of The Creation of Wing Chun: A Social History of the Southern Chinese Martial Arts (SUNY, 2015). He is also author of the long-running martial arts studies blog, Kung Fu Tea: Martial Arts History, Wing Chun and Chinese Martial Studies (www.chinesemartialstudies.com). THE SEVEN FORMS OF LIGHTSABER COMBAT HYPER-REALITY AND THE INVENTION OF THE MARTIAL ARTS BENJAMIN N. JUDKINS DOI ABSTRACT 10.18573/j.2016.10067 Martial arts studies has entered a period of rapid conceptual development. Yet relatively few works have attempted to define the ‘martial arts’, our signature concept. This article evaluates a number of approaches to the problem by asking whether ‘lightsaber combat’ is a martial art. Inspired by a successful film KEYWORDs franchise, these increasingly popular practices combine elements of historical swordsmanship, modern combat sports, stage Star Wars, Lightsaber, Jedi, Hyper-Real choreography and a fictional worldview to ‘recreate’ the fighting Martial Arts, Invented Tradition, Definition methods of Jedi and Sith warriors. The rise of such hyper- of ‘Martial Arts’, Hyper-reality, Umberto real fighting systems may force us to reconsider a number of Eco, Sixt Wetzler. questions. What is the link between ‘authentic’ martial arts and history? Can an activity be a martial art even if its students and CITATION teachers do not claim it as such? Is our current body of theory capable of exploring the rise of hyper-real practices? Most Judkins, Benjamin N. importantly, what sort of theoretical work do we expect from 2016. -

1001 Years of Missing Martial Arts

1001 Years of Missing Martial Arts IMPORTANT NOTICE: Author: Master Mohammed Khamouch Chief Editor: Prof. Mohamed El-Gomati All rights, including copyright, in the content of this document are owned or controlled for these purposes by FSTC Limited. In Deputy Editor: Prof. Mohammed Abattouy accessing these web pages, you agree that you may only download the content for your own personal non-commercial Associate Editor: Dr. Salim Ayduz use. You are not permitted to copy, broadcast, download, store (in any medium), transmit, show or play in public, adapt or Release Date: April 2007 change in any way the content of this document for any other purpose whatsoever without the prior written permission of FSTC Publication ID: 683 Limited. Material may not be copied, reproduced, republished, Copyright: © FSTC Limited, 2007 downloaded, posted, broadcast or transmitted in any way except for your own personal non-commercial home use. Any other use requires the prior written permission of FSTC Limited. You agree not to adapt, alter or create a derivative work from any of the material contained in this document or use it for any other purpose other than for your personal non-commercial use. FSTC Limited has taken all reasonable care to ensure that pages published in this document and on the MuslimHeritage.com Web Site were accurate at the time of publication or last modification. Web sites are by nature experimental or constantly changing. Hence information published may be for test purposes only, may be out of date, or may be the personal opinion of the author. Readers should always verify information with the appropriate references before relying on it. -

Silambam Fencing”

Tamil Nadu Physical Education and Sports University Chennai – 600 006. Name of the Course : Diploma in “SILAMBAM FENCING” Educational Qualification : 12th Standard Stream : Distance Education Duration : Six Months Tamil Nadu Physical Education and Sports University Chennai – 600 006. Diploma in “SILAMBAM FENCING” DISTANCE EDUCATION SYLLABUS Paper Code Name of the Subject Total DCISF101 Fundamentals and Methods of Silambam 100 Fencing Practices DCISF102 Anatomy and Physiology 100 DCISF103 Practical I - on Silambam Fencing 100 DCYP104 Practical II – on Silambam Fencing 100 TOTAL 400 Tamil Nadu Physical Education and Sports University Chennai – 600 006. Diploma in “SILAMBAM FENCING” DISTANCE EDUCATION SYLLABUS Paper Name of the Paper Internal External Total No. Marks I. Fundamentals and Methods of 25 75 100 Silambam Fencing II. Anatomy and Physiology 25 75 100 Practical I. Practical – I 25 75 100 II. Practical – II 25 75 100 TOTAL 100 300 400 PAPER I : Fundamentals and Methods of Silambam Fencing Practices Unit I Definition : Silambam – Etymology – Silambam Fencing – Martial Art – Duel – Combat – Need – Scope – Philosophy – Silambalogy Unit II Misconception – Conversion of Silambam Fencing as a Combative Martial Sport since 1940 AD – “Quarter Staff” of England Akin to Silambam Fencing – Benefits of Silambam Fencing. Unit III Aims and Objectives as per the charter of the International Silambam Fencing Association founded on the 14th December 1975 – Benefits:- As 22 Doctors in Physical Education in India and USA. Unit IV Origin and Development -

Misunderstood Mr. Burr: His Duel with Hamilton Clarence J

Notre Dame Law Review Volume 2 | Issue 2 Article 2 12-1-1926 Misunderstood Mr. Burr: His Duel with Hamilton Clarence J. Ruddy Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Clarence J. Ruddy, Misunderstood Mr. Burr: His Duel with Hamilton, 2 Notre Dame L. Rev. 50 (1926). Available at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndlr/vol2/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by NDLScholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Notre Dame Law Review by an authorized administrator of NDLScholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CURIOSITIES OF THE LAW THE MISUNDERSTOOD MR. BURR: HIS DUEL WITH HAMILTON Fifty years ago anyone attempting to defend Aaron Burr of criminality in his duel with Alexander Hamilton would have aroused immediate and vicious antagonism. It was a settled convicton of all men that Burr was a dastardly murderer, and that his part in the lamentable affair with Hamilton was one of the most atrocious crimes ever committed in this country. People profoundly believed that Burr was thoroughly bad-as Benedict Arnold was bad-and anyone who tried to change that belief was himself either an igno- ramus or a perjurer of truth. Few, of course, gave reasons why Burr was wrong and Hamilton right, but reasons were not necessary. The truth was so evident that it needed no philosophic demonstra- tion. Of late, however, people seem less disposed to condemn a man to eternal ignominy upon the doubtful evidence of legend, and pre- fer to study for themselves the reliable documents of our early na- tional life, so that they may decide with a greater probability of being correct, whether Burr really was so base as he has been de- picted. -

Duel of Theobald Versus Seitz – Germany, 1370

Duel of Theobald versus Seitz – Germany, 1370 translation & commentary by Jeffrey Hull This particular account of judicial duel (kampf) from Germany of 1370 is found in Volume II Chapter 14 of the fechtbuch (fight-book) De Arte Athletica (aka Liber Artis Athleticae – Cod.icon. 393 – circa 1542) by that citizen of Augsburg and fencer called Paulus Hector Mair. Although his Latin recounting is nearly two centuries after the event, it does read with authority, as Mair was the practically peerless fencing historian of 16th Century Germany (1). A similar account is found in Augsburger Chronik (circa 1457) by Sigismund Meisterlin (2). Mair’s account is highly interesting, not just for its description of martial techniques, but also for its description of legal proceeding and dueling-day ritual. And indeed, all that Mair describes here is readily corroborated by, or does not conflict with, other fight-books. It is one of many accounts from late 14th Century, during the time when the eventual grandmaster of Kunst des Fechtens, Johann Liechtenauer, must have been ascending as a young knight and martial artist. My translation is based upon Josef Würdinger’s summarising German translation of Mair’s original Latin recounting, but with comparison to Mair’s original made to corroborate and clarify certain points. Würdinger’s translation was reprinted recently (2006) by Hans Edelmaier (see Bibliography). Lastly – I have made occasional interpolations and several textual notes, as such seemed needed to make these events more comprehensible to the modern reader. ~ ***** In the course of one of the feuds which Duke Stephan had to endure and counter by arrests in Swabia (3) during the years 1369 and 1370, this did happen: A Swabian noble, Theobald Giß von Gißenberg, accused his peer, Seitz von Altheim, of robbery (4) in presence of the Duke. -

Stage Combat Character Analysis

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Theatre Faculty Research Theatre 3-2009 A Violent Character: Stage Combat Character Analysis T. Fulton Burns Follow this and additional works at: https://mds.marshall.edu/theatre_faculty Part of the Acting Commons Stage Combat Character Analysis By T. Fulton Burns It is so deceptively easy stating who your character is but it is over looked more often than you may think. A good character analysis is important in the actor/character relationship and here we will look at the key elements of character research and their specific relationships to the stage combatant. If you want a great source to consider I highly recommend Uta Hagen’s Respect for Acting because it has one of the most concise research options available. She lists her character analysis as follows: • Who am I? Character Characters in Romeo and Juliet have • What time is it? Century, year, season, day, minute training in combative techniques and this • Where am I? Country, city, neighborhood, level of expertise even reveals social status. Tybalt is a wonderful example because he house, room, area of room prides himself on his fighting abilities. One • What surrounds? Animate and inanimate objects could even argue that fighting and pride are all that he knows. The hatred he holds • What are the given circumstances? Past, present, future, and the towards another family (Montagues) based events upon principle and/or teaching, also molds him as a character. Also, how he fights is • What is my relationship? Relation to total events, other based upon the training he has received in characters, and to things his formative years. -

Moss Has Training in Fencing and Stage Combat, and He Regularly Attends

or as long as you’ve been teaching, the students to be safe. They’ll know Moss has training in fencing and you’ve had in your mind that perfect how to make it a part of the show, stage combat, and he regularly attends play to direct—a Shakespearean trag- rather than a fight that interrupts the workshops to keep his skills sharp. “For edy, say. Maybe Romeo and Juliet. acting. They can teach the students me,” he says, “the reality of being in a Now you have the actors who can things the teacher might not know. small school where you’re a one-stop carry it. The administration is behind “We don’t teach you how to fight. shop anyway is when I have money, I you. Your students are thrilled. We teach you how to act with vio- would rather spend it on an expertise I There’s just one problem. Almost lence. You want to learn how to fight, don’t have myself.” before you can bite your thumb, you can go watch wrestling,” says Both Martin and Rodgers hire chore- there’s a brawl with naked blades in New York-based fight director ographers, but they’ve also gained Act I, scene one. The year might be Michael Chin, who recently earned enough experience to teach or choreo- right for Shakespeare, but you have the title of fight master from the Soci- graph some of the basics without out- better things to do than face disas- ety of American Fight Directors. (He’s side help. -

IMCF Rules 2020

International Medieval Combat Federation www.medieval-combat.org [email protected] IMCF Rules and Regulations V.04 Safety, honour, sportsmanship, and fair competition are the hallmarks of the International Medieval Combat Federation (IMCF). All competitors are expected to behave with regard for the wellbeing of other combatants. This sport has inherent risks; it is the duty of the officiating staff to enforce the following to maintain a safe, level playing field in this fierce but honourable contest. Welcome to the family! Table of Contents 1. Equipment ....................................................................................................................................... 2 1.1. Armour .................................................................................................................................... 2 1.1.1. Helmets ........................................................................................................................... 2 1.1.2. Torso and Limbs .............................................................................................................. 2 1.1.3. Hands .............................................................................................................................. 3 1.2. Weapons ................................................................................................................................. 3 1.2.8. Swords ............................................................................................................................. 4 1.2.9. -

Duel Personality

NEW ORLEANS NOSTALGIA Remembering New Orleans History, Culture and Traditions By Ned Hémard Duel Personality In days of yore when a court of law did not seem the appropriate solution to libel or slander, the duel (especially in New Orleans) was considered an excellent resource for recovery of reputation. More duels were fought during the 1830s in the Crescent City than in any other city in the world. Louisiana Historian Alcée Fortier wrote that on a single Sunday in 1839 ten duels were fought in New Orleans. The word duel from the Latin duellum, an archaic form of bellum, originally signified a legal method of solving a private matter. By the time it came to New Orleans it was an extrajudicial avenue for settling a private affront. It was conducted according to twenty-six points of the Code Duello, adopted in 1777 in Ireland, of all places. It seems as if the gentlemen of Tipperary, Galway, Mayo, Sligo and Roscommon needed some ground rules so as to avoid a donnybrook. And it was only for gentlemen since they would only duel those of their own social standing, even though the insults would indicate otherwise. Dueling in City Park in 1841 In 1722, only four years after the founding New Orleans, Bienville outlawed dueling. Both the French and Spanish administrations had tough laws against dueling, but they were not enforced. In 1812, when Louisiana became a state, dueling was illegal. An “Association Against Dueling” was formed in New Orleans in 1834, but Creole tempers still flared. In 1855 the New Orleans police began to enforce the laws on the books against dueling, and a number of arrests and prosecutions were made. -

Grappling As Projected in the Archaeological Finds of Ancient and Medieval India

Grappling as Projected in the Archaeological Finds of Ancient and Medieval India Kush Dhebar1 1. 505, Technology Apartment, 24 IP Extension, Delhi – 110 092, New Delhi, India (Email: [email protected]) Received: 16 July 2018; Revised: 08 September 2018; Accepted: 17 October 2018 Heritage: Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies in Archaeology 6 (2018): 908‐925 Abstract: Grappling as an unarmed form of combat that has been prevalent in India since the ancient times. Grappling included present day forms of wrestling, Pehelvani, Jiu‐Jitsu, Judo and classical pugilism. Ancient Indian literature is full of references of grappling and other martial arts but along with that India has an undying tradition of archaeological evidences of grappling in the form of sculptures and terracotta plates on Indian monuments right from the Sunga‐ Kushana period to the VIjayanagara period. Keywords: Archaeology, Wrestling, Grappling, Jiu‐Jitsu, Iconography, Mallayuddha, Mushti‐Yuddha Introduction Ancient India had great and widespread martial and physical traditions. Martial Arts practiced by martial artists was known as Mallavidya. This mallavidya was practiced in earthen mud pits known as Akhadas in North India, Talim in Maharashtra and Garadi Mane in Karnataka. The mallavidya that we see today is more or less restricted to wrestling and grappling, but during the ancient times there are references of striking like punches, knees and elbows also being used. For example, in the Harivamsha Purana there are famous bouts between Lord Krishna and his brother Balarama and wrestlers Chanura and Mushtika. If one reads the Purana one can see how fists and knees were used by the wrestlers during the bouts. -

If We Allow Football Players and Boxers to Be Paid for Entertaining the Public, Why Donâ•Žt We Allow Kidney Donors to Be

COOK_KRAWIEC_PAGINATED (DO NOT DELETE) 5/9/2018 10:50 AM IF WE ALLOW FOOTBALL PLAYERS AND BOXERS TO BE PAID FOR ENTERTAINING THE PUBLIC, WHY DON’T WE ALLOW KIDNEY DONORS TO BE PAID FOR SAVING LIVES? PHILIP J. COOK & KIMBERLY D. KRAWIEC* I INTRODUCTION The law regulates and sometimes prohibits activities that harm others. In addition, the law occasionally regulates or prohibits activities primarily because they create health and safety risks to the participants themselves. Such paternalistic regulations are readily justified when applied to children, adults who are mentally ill or cognitively limited, or those who are temporarily incapacitated (for example, due to intoxication). When applied to adults of sound mind, however, purely paternalistic laws can be challenged as an over reach of government, an imposition on individual autonomy and liberty.1 Nonetheless, a variety of paternalistic laws are on the books.2 These laws regulate, tax, or prohibit risky activities. We are particularly interested in one of these risky activities, namely kidney donation by living donors. Although living kidney donation is a common medical procedure and donors usually enjoy a full recovery, the loss of a kidney poses long-term health risks, in particular that of renal failure should the donor’s remaining kidney fail.3 In the United States and most every other country (with the notable exception of Iran), kidney donation Copyright © 2018 by Philip J. Cook and Kimberly D. Krawiec. This article is also available online at http://lcp.law.duke.edu/. * Terry Sanford Professor Emeritus of Public Policy, Sanford School of Public Policy, Professor Emeritus of Economics and Sociology, Duke University; Kathrine Robinson Everett Professor of Law, Duke University School of Law, Senior Fellow, Kenan Institute for Ethics, Duke University. -

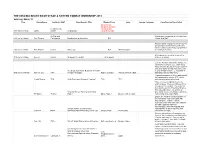

The Virginia Beach Bash Stage & Screen Combat Workshop 2019

THE VIRGINIA BEACH BASH STAGE & SCREEN COMBAT WORKSHOP 2019 Saturday, March 30 Time Venue/Space Instructor/Staff Class/Session Title Weapon/Form Level Camera Coverage Class/Session Description All personal weapons must be Head Intern & checked and 8:00 am to 8:30 am Lobby Interns Registration cleared by staff. All Staff and Workshop is introduced to the Instructors, 8:30 am to 9:00 am Main Theater Participants Introductions & Orientation N/A Interns, and Staff All participants engage mind and body by partipating in mild stretching and a little cardio to warm-up the body in preparation 9:00 am to 9:15 am Main Theater Interns Warm-ups N/A All Participants for the day's activities. All weapons are checked in and out in 9:15 am to 9:30 am Armory Interns Weapons Check-Out All weapons between sessions. Let's use fundamentals and technique as catalyst for delving deeper, challenging focus in nuanced sequencing, precision in targeting, clarity of blade-trajectory, and "Clean up your Act!!!": Bi-Lateral Precision clearity in fight narrative. Let's get rid of 9:30 am to 10:45 am Main Theater Chin in Rapier & Dagger Rapier & Dagger Advanced/Intermediate bad habits and our R&D skills. Preparation session for those participants have arranged to take an SPR; review Studio Theater TBA Skills Proficiency Renewal: Session 1 TBA TBD and choreography is introduced When it comes to fighting for you life anything goes. Marques of Queensbury rules go out the window. You stab, cut, kick, punch, and bite if that what it takes.