Coversheet for Thesis in Sussex Research Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Universidad Peruana De Ciencias Aplicadas Facultad

Caracterización de los procesos de consumo de los K- Dramas y videos musicales de K-Pop, y su incidencia en la construcción de la identidad y formas de socialización en la comunidad Hallyu de Lima. Una aproximación desde los fenómenos de audiencia en K-Dramas Descendants of the Sun y Goblin: The Lonely and Great God, y los fenómenos de tendencia musical de los grupos BIG BANG y Bangtan Boys; Beyond The Scene a.k.a BTS Item Type info:eu-repo/semantics/bachelorThesis Authors Mosquera Anaya, Heidy Winie Publisher Universidad Peruana de Ciencias Aplicadas (UPC) Rights info:eu-repo/semantics/openAccess; Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International Download date 10/10/2021 11:56:20 Item License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10757/648589 UNIVERSIDAD PERUANA DE CIENCIAS APLICADAS FACULTAD DE COMUNICACIONES PROGRAMA ACADÉMICO DE COMUNICACIÓN AUDIOVISUAL Y MEDIOS INTERACTIVOS Caracterización de los procesos de consumo de los K-Dramas y videos musicales de K-Pop, y su incidencia en la construcción de la identidad y formas de socialización en la comunidad Hallyu de Lima. Una aproximación desde los fenómenos de audiencia en K-Dramas Descendants of the Sun y Goblin: The Lonely and Great God, y los fenómenos de tendencia musical de los grupos BIG BANG y Bangtan Boys; Beyond The Scene a.k.a BTS. TESIS Para optar el título profesional de Licenciado en Comunicación Audiovisual y Medios Interactivos AUTOR(A) Mosquera Anaya, Heidy Winie (0000-0003-4569-9612) ASESOR(A) Calderón Chuquitaype, Gabriel Raúl (0000-0002-1596-8423) Lima, 01 de Junio de 2019 DEDICATORIA A mis padres Abraham y Luz quienes con su amor, paciencia y esfuerzo me han permitido llegar a cumplir hoy un sueño más. -

Das Große Archiv Der Deutschen Bahnhöfe

Strüber, Oliver [vormals Preuß, Erich] (Hrsg.): Das große Archiv der deutschen Bahnhöfe. Loseblattsammlung, 8 Bände, Grundwerk bis einschließlich 156. Ergänzungslieferung, Stand 24.08.2021, 7.010 Seiten. GeraNova Zeitschriftenverlag München. Geschichte Bahnhofstypen 4 Hochbauten (Gebäude) 5 Bahnhöfe A - Z Hochbauten (Gebäude) Aufsichtsbuden Bahnhöfe alphabetisch: A B C D E F G H I J K Automatische Ablaufstell- A L M N O P Q R S T U werke Aachen Hbf V W Z Bahnhofsblock Aalen Gesamtregister Lexikon Bahnhofsdesign Adorf (Vogtl) Gleisplan-ABC Bahnhofsgaststätten Ahrensburg Bahnhofshallen Ahrensfelde 1 Inhalt, Vorwort Bahnhofsnamen Aken (Elbe) Inhaltsverzeichnis Bahnhofstoiletten Alexisbad Bahnsteige Allendorf (Eder) 2 Geschichte Bahnsteigmöbel Allersberg (Rothsee) Abfertigungsbefugnisse Bahnsteigsperre Alsfeld (Oberhess) Abfertigungsstellen im Betriebszentrale Altdorf (b Nürnberg) Kleingutverkehr der DR Blockstellen Altefähr Bahn-Agentur DB PlusPunkt. Klein, aber Altenbeken Bahnhofsbuchhandlung variantenreich Altenberg (Erzgeb) Bahnhofsvorplätze Eisenbahnersiedlungen Altenburg Baustile Elektromechanisches Stell- Altenhundem Denkmalpflege werk Altomünster Der sächsische Bahnhofs- Elektronisches Stellwerk Amberg block Gaselan-Stellwerke Andernach Die Aufsicht Geschäfte. Ein neuer Kurs Angermünde Die Bahnhofsmission [für Empfangsgebäude] Anklam Die Leistung eines Bahnhofs Gleisbildstellwerke Annaberg-Buchholz Einführung (Reise-Kathe- Güterabfertigungen Ansbach dralen) Gleisbremsen I Apolda Gleisbremsen Hochbauten Arenshausen Grußpostkarten (Empfangsgebäude, -

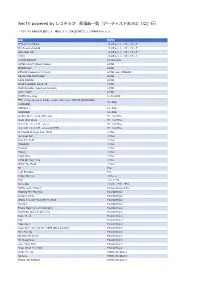

Rectv Powered by レコチョク 配信曲 覧(アーティスト名ヨミ「は」 )

RecTV powered by レコチョク 配信曲⼀覧(アーティスト名ヨミ「は」⾏) ※2021/7/19時点の配信曲です。時期によっては配信が終了している場合があります。 曲名 歌手名 アワイロサクラチル バイオレント イズ サバンナ It's Power of LOVE バイオレント イズ サバンナ OH LOVE YOU バイオレント イズ サバンナ つなぐ バイオレント イズ サバンナ I'M DIFFERENT HI SUHYUN AFTER LIGHT [Music Video] HYDE INTERPLAY HYDE ZIPANG (Japanese Version) HYDE feat. YOSHIKI BELIEVING IN MYSELF HYDE FAKE DIVINE HYDE WHO'S GONNA SAVE US HYDE MAD QUALIA [Japanese Version] HYDE LET IT OUT HYDE 数え切れないKiss Hi-Fi CAMP 雲の上 feat. Keyco & Meika, Izpon, Take from KOKYO [ACOUSTIC HIFANA VERSION] CONNECT HIFANA WAMONO HIFANA A Little More For A Little You ザ・ハイヴス Walk Idiot Walk ザ・ハイヴス ティック・ティック・ブーン ザ・ハイヴス ティック・ティック・ブーン(ライヴ) ザ・ハイヴス If I Could Change Your Mind ハイム Summer Girl ハイム Now I'm In It ハイム Hallelujah ハイム Forever ハイム Falling ハイム Right Now ハイム Little Of Your Love ハイム Want You Back ハイム BJ Pile Lost Paradise Pile I Was Wrong バイレン 100 ハウィーD Shine On ハウス・オブ・ラヴ Battle [Lyric Video] House Gospel Choir Waiting For The Sun Powderfinger Already Gone Powderfinger (Baby I've Got You) On My Mind Powderfinger Sunsets Powderfinger These Days [Live In Concert] Powderfinger Stumblin' [Live In Concert] Powderfinger Take Me In Powderfinger Tail Powderfinger Passenger Powderfinger Passenger [Live At The 1999 ARIA Awards] Powderfinger Pick You Up Powderfinger My Kind Of Scene Powderfinger My Happiness Powderfinger Love Your Way Powderfinger Reap What You Sow Powderfinger Wake We Up HOWL BE QUIET fantasia HOWL BE QUIET MONSTER WORLD HOWL BE QUIET 「いくらだと思う?」って聞かれると緊張する(ハタリズム) バカリズムと アステリズム HaKU 1秒間で君を連れ去りたい HaKU everything but the love HaKU the day HaKU think about you HaKU dye it white HaKU masquerade HaKU red or blue HaKU What's with him HaKU Ice cream BACK-ON a day dreaming.. -

Stardigio Program

スターデジオ チャンネル:408 J-POPピックアップアーティスト 放送日:2021/06/28~2021/07/04 「番組案内 (8時間サイクル)」 開始時間:4:00〜/12:00〜/20:00〜 楽曲タイトル 演奏者名 ■DOBERMAN INFINITY 特集 INFINITY DOBERMAN INFINITY SAY YEAH!! DOBERMAN INFINITY Heartbeat DOBERMAN INFINITY x ELLY (三代目 J Soul Brothers from EXILE TRIBE) JUMP AROUND ∞ DOBERMAN INFINITY いつか DOBERMAN INFINITY GA GA SUMMER DOBERMAN INFINITY D.Island DOBERMAN INFINITY feat. m-flo あの日のキミと今の僕に DOBERMAN INFINITY SUPER BALL DOBERMAN INFINITY YOU & I DOBERMAN INFINITY We are the one DOBERMAN INFINITY 6 -Six- DOBERMAN INFINITY konomama DOBERMAN INFINITY Who the KING? DOBERMAN INFINITY ■FANTASTICS from EXILE TRIBE 特集 OVER DRIVE FANTASTICS from EXILE TRIBE Flying Fish FANTASTICS from EXILE TRIBE Believe in Love FANTASTICS from EXILE TRIBE Dear Destiny FANTASTICS from EXILE TRIBE Every moment FANTASTICS from EXILE TRIBE ターミナル FANTASTICS from EXILE TRIBE Time Camera FANTASTICS from EXILE TRIBE FANTASTIC 9 FANTASTICS from EXILE TRIBE Hey, darlin' FANTASTICS from EXILE TRIBE Winding Road ~未来へ~ FANTASTICS from EXILE TRIBE High Fever FANTASTICS from EXILE TRIBE STOP FOR NOTHING FANTASTICS from EXILE TRIBE Play Back FANTASTICS from EXILE TRIBE M.V.P. FANTASTICS from EXILE TRIBE ■THE RAMPAGE from EXILE TRIBE 特集(1) FIND A WAY THE RAMPAGE from EXILE TRIBE Lightning THE RAMPAGE from EXILE TRIBE ELEVATION THE RAMPAGE from EXILE TRIBE GO ON THE RAMPAGE THE RAMPAGE from EXILE TRIBE FRONTIERS THE RAMPAGE from EXILE TRIBE Knocking Knocking THE RAMPAGE from EXILE TRIBE Dirty Disco THE RAMPAGE from EXILE TRIBE Shangri-La THE RAMPAGE from EXILE TRIBE 100degrees -

Download Bigbang Made Full Album Japanese K2nblog Zinnia Magenta

download bigbang made full album japanese k2nblog Zinnia Magenta. Download Musik, MV/PV Jepang & Korea Full Version + Drama Korea Subtittle Indonesia. Newest Post. Download [Album] BIGBANG - MADE. BIGBANG – MADE [FULL ALBUM] Release Date: 2016.12.13 Genre: Rap / Hip-hop, Ballad, Dance, Folk, Rock Language: Korean Bit Rate: MP3-320kbps + iTunes Plus AAC M4A Big Bang’s tenth anniversary project comes to an end with the last album of the Made series. Besides the Made singles, such as Bang Bang Bang, Loser, Bae Bae and “Let’s Not Fall in Love,” the album also features three new tracks, namely the double title numbers FXXK IT and Last Dance, as well as Girlfriend written by G-Dragon, TOP and YG in-house producer Teddy. Track List: 01. 에라 모르겠다 (FXXK IT) *Title 02. LAST DANCE *Title 03. GIRLFRIEND 04. 우리 사랑하지 말아요 (LET’S NOT FALL IN LOVE) 05. LOSER 06. BAE BAE 07. 뱅뱅뱅 (BANG BANG BANG) 08. 맨정신 (SOBER) 09. IF YOU 10. 쩔어 (ZUTTER) (GD & T.O.P) 11. WE LIKE 2 PARTY. Download Album File: BIGBANG – MADE [Zinnia Magenta].rar Size: 95.9 MB. Download bigbang made full album japanese k2nblog. BIG BANG Albums Download. BIGBANG – Alive (Monster Edition) 1. Still Alive 2. MONSTER 3. FANTASTIC BABY 4. Blue 5. Love Dust 6. FEELING 7. Ain't No Fun 8. BAD BOY 9. EGO 10. Wings 11. Bingle Bingle 12. Haru Haru (Japanese ver.) DOWNLOAD. BIGBANG - Still Alive Special Edition. 1. Still Alive 2. MONSTER 3. Feeling 4. FANTASTIC BABY 5. BAD BOY 6. Blue 7. Round and Round 빙글빙글 (Bingeul Bingeul) 8. -

The Motion Picture Director (1925-1926)

MOTION PICTURE ^ / rrL£ Annie Beginning a Neiv Series WHY HOLLYWOOD? By EDWIN CAREWE Also Two Notable Serials THUNDERING SILENCE THE NIGHT BRIDE By H. H. Van Loan By Frederic Chapin At The Director’s Service! A new, fast-moving, Portable Unit of tre- mendous power — com- pletely self-contained — for broad SOUND- CASTING, makes its bid for Movie Fame in this issue of The Director. Now you can sway that “seething mob” with absolute comfort to your- self and your staff. Terms of rental on application. TUcker 3148 ? MOTION PICTURE Volume Two September Number Three 19 2 5 Dedicated to the Creation of a Better Understanding Between Those Who Make and Those Who See Motion Pictures OLKS, meet the “new” by and for the people of that Director; new in dress industry, and yet possessing F neither the limitations of the and in its increased num- CONTENTS ber of pages, and new in its strictly class or trade publica- added features of interest and Page tion, nor the diverified appeal entertainment value, but, in of the so-called “fan” maga- IN THE DIRECTOR’S CHAIR 5 spirit of helpfulness and sincere zines. George L. Sargent concern for the best interests Insofar as it may be possible 8 of the industry of which it is A TALE OF TEMPERAMENT The Director will endeavor a part, the same Director you George Landy to steer a middle course between these two have known in the past. CAMERA STUDIES OF SCREEN groups and cordially In the development of the solicits the co-operation of all 9 PERSONALITIES are “new” Director it is our pur- who actively concerned with pose, as we enter upon the WHY HOLLYWOOD? (A Series) 17 the making of motion pictures. -

1 : Daniel Kandi & Martijn Stegerhoek

1 : Daniel Kandi & Martijn Stegerhoek - Australia (Original Mix) 2 : guy mearns - sunbeam (original mix) 3 : Close Horizon(Giuseppe Ottaviani Mix) - Thomas Bronzwaer 4 : Akira Kayos and Firestorm - Reflections (Original) 5 : Dave 202 pres. Powerface - Abyss 6 : Nitrous Oxide - Orient Express 7 : Never Alone(Onova Remix)-Sebastian Brandt P. Guised 8 : Salida del Sol (Alternative Mix) - N2O 9 : ehren stowers - a40 (six senses remix) 10 : thomas bronzwaer - look ahead (original mix) 11 : The Path (Neal Scarborough Remix) - Andy Tau 12 : Andy Blueman - Everlasting (Original Mix) 13 : Venus - Darren Tate 14 : Torrent - Dave 202 vs. Sean Tyas 15 : Temple One - Forever Searching (Original Mix) 16 : Spirits (Daniel Kandi Remix) - Alex morph 17 : Tallavs Tyas Heart To Heart - Sean Tyas 18 : Inspiration 19 : Sa ku Ra (Ace Closer Mix) - DJ TEN 20 : Konzert - Remo-con 21 : PROTOTYPE - Remo-con 22 : Team Face Anthem - Jeff Mills 23 : ? 24 : Giudecca (Remo-con Remix) 25 : Forerunner - Ishino Takkyu 26 : Yomanda & DJ Uto - Got The Chance 27 : CHICANE - Offshore (Kitch 'n Sync Global 2009 Mix) 28 : Avalon 69 - Another Chance (Petibonum Remix) 29 : Sophie Ellis Bextor - Take Me Home 30 : barthez - on the move 31 : HEY DJ (DJ NIKK HARDHOUSE MIX) 32 : Dj Silviu vs. Zalabany - Dearly Beloved 33 : chicane - offshore 34 : Alchemist Project - City of Angels (HardTrance Mix) 35 : Samara - Verano (Fast Distance Uplifting Mix) http://keephd.com/ http://www.video2mp3.net Halo 2 Soundtrack - Halo Theme Mjolnir Mix declub - i believe ////// wonderful Dinka (trance artist) DJ Tatana hard trance ffx2 - real emotion CHECK showtek - electronic stereophonic (feat. MC DV8) Euphoria Hard Dance Awards 2010 Check Gammer & Klubfiller - Ordinary World (Damzen's Classix Remix) Seal - Kiss From A Rose Alive - Josh Gabriel [HQ] Vincent De Moor - Fly Away (Vocal Mix) Vincent De Moor - Fly Away (Cosmic Gate Remix) Serge Devant feat. -

Planfeststellungsbeschluss Des Eisenbahn-Bundesamtes Vom 19.02.2010 (Az

Außenstelle Berlin Steglitzer Damm 117 12169 Berlin Az. 511ppa/002-436 Datum: 22.05.2017 Ausfertigung Planfeststellungsbeschluss gemäß § 18 AEG für das Vorhaben Ausbau Knoten Berlin, Berlin Südkreuz – Blankenfelde („Dresdner Bahn“), Planfeststellungsabschnitt 1, Abzw Berlin-Mariendorf – EÜ Schichauweg Bahn-km 6,062 – 12,300 der Strecken 6135 Berlin - Elsterwerda 6035 Berlin - Blankenfelde Vorhabensträger: DB Netz AG, DB Station&Service AG, DB Energie GmbH, diese vertreten durch DB Netz AG Regionalbereich Ost Umgehungsstraße 2 12529 Berlin Planfeststellungsbeschluss gemäß § 18 AEG für das Vorhaben "Ausbau Knoten Berlin, Bln Südkreuz – Blankenfelde, PFA 1 Abzw Bln-Mariendorf – EÜ Schichauweg", Bahn-km 6,062 – 12,300 der Strecke 6135 Berlin – Elsterwerda Az. 511ppa/002-436 vom 22.05.2017 Seite 2 von 435 Planfeststellungsbeschluss gemäß § 18 AEG für das Vorhaben "Ausbau Knoten Berlin, Bln Südkreuz – Blankenfelde, PFA 1 Abzw Bln-Mariendorf – EÜ Schichauweg", Bahn-km 6,062 – 12,300 der Strecke 6135 Berlin – Elsterwerda Az. 511ppa/002-436 vom 22.05.2017 INHALTSVERZEICHNIS A. VERFÜGENDER TEIL ........................................................................................... 7 A.1 Feststellung des Plans ........................................................................................... 7 A.1.1 Vorbehaltsauflösung und Änderung des Landschaftspflegerischen Begleitplans zum Planfeststellungsbeschluss für den PFA 2 ...................................................... 8 A.1.2 Vorbehalt bzgl. der Zugänge zum S-Bahnhaltepunkt Buckower -

Einfahrtverbot Für Dampflokgetriebene Züge (Unterirdische Personenverkehrsanlagen)

Personenbahnhöfe der DB Station&Service AG, die von Ziffer 4.7 INBP-BT erfasst sind Einfahrtverbot für dampflokgetriebene Züge (unterirdische Personenverkehrsanlagen) Stand: Juli 2021 Bundesland Bahnhof Baden-Württemberg Filderstadt Baden-Württemberg Stuttgart Feuersee Baden-Württemberg Stuttgart Flughafen Baden-Württemberg Stuttgart Hauptbahnhof * Baden-Württemberg Stuttgart Schwabstraße Baden-Württemberg Stuttgart Stadtmitte Baden-Württemberg Stuttgart Universität Bayern lsmaning Bayern München Flughafen Bayern München Hauptbahnhof * Bayern München lsartor Bayern München Karlsplatz Bayern München Marienplatz Bayern München Rosenheimer Platz Bayern Unterföhring Berlin Berlin Hauptbahnhof (auch oberirdisch) Berlin Berlin Anhalter Bahnhof Berlin Berlin Brandenburger Tor Berlin Berlin Friedrichstraße * Berlin Berlin Nordbahnhof Berlin Berlin Potsdamer Platz Berlin Berlin Oranienburger Straße Berlin Flughafen Berlin Brandenburg Hamburg Hamburg Airport (Flughafen) Hamburg Hamburg Hauptbahnhof * Hamburg Hamburg Altona * Hamburg Hamburg Harburg * Hamburg Harburg Rathaus Hamburg Heimfeld Hamburg Jungfernstieg Hamburg Königstraße Hamburg Landungsbrücken Hamburg Reeperbahn Hamburg Stadthausbrücke Hessen Frankfurt (Main) Flughafen Regionalbahnhof Hessen Frankfurt (Main) Gateway Gardens Hessen Frankfurt (Main) Hauptwache Hessen Frankfurt (Main) Hauptbahnhof * Hessen Frankfurt (Main) Konstablerwache Hessen Frankfurt (Main) Lokalbahnhof Hessen Frankfurt (Main) Mühlberg Hessen Frankfurt (Main) Ostendstraße Hessen Frankfurt (Main) Taunusanlage Hessen -

Upva) Und Oberirdischen Personenverkehrsanlagen Mit Bahnsteighallen

Übersicht zu Bahnhöfen mit unterirdischen Personenverkehrsanlagen (uPVA) und oberirdischen Personenverkehrsanlagen mit Bahnsteighallen Bahnhof mit uPVA Bahnhof mit Bahnsteighalle Berlin Anhalter Bahnhof Aachen Hbf Berlin Brandenburger Tor Alexanderplatz Berlin Hauptbahnhof Bad Ems Berlin Potsdamer Platz Bellevue Berlin-Friedrichstraße Berlin Hauptbahnhof Berlin-Nordbahnhof Berlin Ostbahnhof Dortmund-Dorstfeld Berlin Südkreuz Dortmund-Dorstfeld Süd Berlin Zoologischer Garten Dortmund-Lütgendortmund Berlin-Friedrichstraße Dortmund-Universität Berlin-Spandau Dresden Flughafen Berlin-Westkreuz Filderstadt Bonn Hbf Flughafen München Bremen Hbf Frankfurt (Main) Flughafen Regionalbahnhof Chemnitz Hbf Frankfurt (Main) Gateway Gardens Darmstadt Hbf Frankfurt (Main) Hauptwache Dresden Hbf Frankfurt (Main) Hbf Dresden-Neustadt Frankfurt (Main) Konstablerwache Duisburg Hbf Frankfurt (Main) Lokalbahnhof Düsseldorf Hbf Frankfurt (Main) Mühlberg Elbbrücken Frankfurt (Main) Ostendstraße Erfurt Hbf Frankfurt (Main) Taunusanlage Frankfurt (Main) Hbf Halle-Neustadt Frankfurt (Oder) Hamburg Airport (Flughafen) Frankfurt am Main Flughafen Fernbahnhof Hamburg Hbf Gera Hbf Hamburg-Altona Görlitz Hamburg-Harburg Hackescher Markt Hannover-Flughafen Hagen Hbf Harburg Rathaus Halle (Saale) Hbf Hattingen (Ruhr) Mitte Hamburg Dammtor Heimfeld Hamburg Hbf Ismaning Jannowitzbrücke (S-Bahn Berlin) Jungfernstieg Karlsruhe Hbf DB Station&Service AG Vertrieb Mobility (I.SVM) Europaplatz 1, 10557 Berlin Stand: April 2020 Bahnhof mit uPVA Bahnhof mit Bahnsteighalle Köln/Bonn -

Standorte Und Rufnummern DB Reinigungsteam

Bahnhof Rufnummer Ahaus +49 157 923 974 02 Ahlen (Westf) +49 157 923 974 02 Ahrensfelde +49 157 923 628 36 Alexanderplatz +49 157 923 628 36 Altena (Westf) +49 157 923 974 02 Altenbeken +49 157 923 974 02 Altenberge +49 157 923 974 02 Altenseelbach +49 157 923 974 02 Altglienicke +49 157 923 628 36 Alt-Reinickendorf +49 157 923 628 36 Ardey +49 157 923 974 02 Arnsberg (Westf) +49 157 923 974 02 Arnsberg-Neheim-Hüsten +49 157 923 974 02 Aschaffenburg Hbf +49 157 923 974 31 Ascheberg (Westf) +49 157 923 974 02 Attendorn +49 157 923 974 02 Attendorn Hohen-Hagen +49 157 923 974 02 Attilastraße +49 157 923 628 36 Aue-Wingeshausen +49 157 923 974 02 Augsburg Hbf +49 157 923 974 31 Babelsberg +49 157 923 628 36 Bad Berleburg +49 157 923 974 02 Bad Driburg (Westf) +49 157 923 974 02 Bad Holzhausen +49 157 923 974 02 Bad Oeynhausen +49 157 923 974 02 Bad Oeynhausen Süd +49 157 923 974 02 Bad Salzuflen +49 157 923 974 02 Bad Sassendorf +49 157 923 974 02 Balve +49 157 923 974 02 Bamberg +49 157 923 974 31 Baumschulenweg +49 157 923 628 36 Beelen +49 157 923 974 02 Bellevue +49 157 923 628 36 Bergfelde (b Berlin) +49 157 923 628 36 Berghausen +49 157 923 974 02 Beringhausen +49 157 923 974 02 Berlin Anhalter Bahnhof +49 157 923 628 36 Berlin Brandenburger Tor +49 157 923 628 36 Berlin Frankfurter Allee +49 157 923 628 36 Berlin Hauptbahnhof +49 157 923 628 36 Berlin Ostbahnhof +49 157 923 628 36 Berlin Potsdamer Platz +49 157 923 628 36 Berlin Südkreuz +49 157 923 628 36 Berlin Zoologischer Garten +49 157 923 628 36 Berlin-Adlershof +49 157 923 628 -

Bigbang Beautiful Hangover

Beautiful Hangover BigBang Kimi wa my beautiful hangover Hangover yeah Kimi wa my beautiful hangover, hangover Kagayaku headlight nemuranai machi e ARE YOU READY? Koko kara ga shoubu ASE-razu ni genkai made zenkai de ikou! Nagareru RADIO chijimeru kyori yo OH OH OH Yukisaki wa mada ienai yo HONEY, CLOSE YOUR EYES We're gonna get down down down! Gimme LOVE LOVE LOVE! Sagashi motometeta Lady Dare ni motomerarenai MAKING LOVE kiga sumumate GO! Kimi wa My Beautiful Hangover(ay) Hangover(ay) yeah Kimi wa my beautiful hangover(ay) hangover(ay) It's me G.D (I know you love me) Ma-Ma-Ma-Ma-Ma beautiful girl 1, 2, 3 to the 4-sho one like you There ain't nobody can do them things you do So true I'm so excited delighted I won't deny it nor fight it Baby you got what I need Got me jumpin' jumpin' off my feet Baby there's no playin' delayin' Always got me feelin' that healin' Everyday I'm smilin' and wildin' When I think about you Think about you Got me flyin' so high'n And I won't stop bringin' and bringin' that (BANG) B.I.G (BANG! ) T.O.P (BANG! ) Baby that's how it be We're gonna get down down down! Gimme love love love! Sagashi motometeta LADY Dare ni motomerarenai MAKING LOVE honoo no yo ni atsuku Kimi wa my beautiful hangover(ay) Hangover(ay) yeah Kimi wa my beautiful hangover(ay) hangover(ay) You got my heart, LOVE GAME Makes me crazy baby Kiss my lips kuruwa se 360° Mou nara you ni naru shikanai, yeah We're gonna get down down down Gimme LOVE LOVE LOVE! Sagashi motometeta Lady Dare ni motomerarenai Making Love kiga sumumate GO! Kimi wa my beautiful(beautiful ay) hangover(hangover) Hangover(hangover) yeah(hangover yo, what?) Kimi wa my beautiful(beautiful ay) hangover(hangover) hangover(hangover) Yeah ready lets go What a life to wake up in love Every time I can't get enough Of your kindness, sweetness, I don't want it ever to end So amazing, all the above, In a way you take you show love You define us and I just..