First Contact Between Ya'qūb Beg and the Qing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Selected Works of Chokan Valikhanov Selected Works of Chokan Valikhanov

SELECTED WORKS OF CHOKAN VALIKHANOV CHOKAN OF WORKS SELECTED SELECTED WORKS OF CHOKAN VALIKHANOV Pioneering Ethnographer and Historian of the Great Steppe When Chokan Valikhanov died of tuberculosis in 1865, aged only 29, the Russian academician Nikolai Veselovsky described his short life as ‘a meteor flashing across the field of oriental studies’. Set against his remarkable output of official reports, articles and research into the history, culture and ethnology of Central Asia, and more important, his Kazakh people, it remains an entirely appropriate accolade. Born in 1835 into a wealthy and powerful Kazakh clan, he was one of the first ‘people of the steppe’ to receive a Russian education and military training. Soon after graduating from Siberian Cadet Corps at Omsk, he was taking part in reconnaissance missions deep into regions of Central Asia that had seldom been visited by outsiders. His famous mission to Kashgar in Chinese Turkestan, which began in June 1858 and lasted for more than a year, saw him in disguise as a Tashkent mer- chant, risking his life to gather vital information not just on current events, but also on the ethnic make-up, geography, flora and fauna of this unknown region. Journeys to Kuldzha, to Issyk-Kol and to other remote and unmapped places quickly established his reputation, even though he al- ways remained inorodets – an outsider to the Russian establishment. Nonetheless, he was elected to membership of the Imperial Russian Geographical Society and spent time in St Petersburg, where he was given a private audience by the Tsar. Wherever he went he made his mark, striking up strong and lasting friendships with the likes of the great Russian explorer and geographer Pyotr Petrovich Semyonov-Tian-Shansky and the writer Fyodor Dostoyevsky. -

CORE STRENGTH WITHIN MONGOL DIASPORA COMMUNITIES Archaeological Evidence Places Early Stone Age Human Habitation in the Southern

CORE STRENGTH WITHIN MONGOL DIASPORA COMMUNITIES Archaeological evidence places early Stone Age human habitation in the southern Gobi between 100,000 and 200,000 years ago 1. While they were nomadic hunter-gatherers it is believed that they migrated to southern Asia, Australia, and America through Beringia 50,000 BP. This prehistoric migration played a major role in fundamental dispersion of world population. As human migration was an essential part of human evolution in prehistoric era the historical mass dispersions in Middle Age and Modern times brought a significant influence on political and socioeconomic progress throughout the world and the latter has been studied under the Theory of Diaspora. This article attempts to analyze Mongol Diaspora and its characteristics. The Middle Age-Mongol Diaspora started by the time of the Great Mongol Empire was expanding from present-day Poland in the west to Korea in the east and from Siberia in the north to the Gulf of Oman and Vietnam in the south. Mongols were scattered throughout the territory of the Great Empire, but the disproportionately small number of Mongol conquerors compared with the masses of subject peoples and the change in Mongol cultural patterns along with influence of foreign religions caused them to fell prey to alien cultures after the decline of the Empire. As a result, modern days Hazara communities in northeastern Afghanistan and a small group of Mohol/Mohgul in India, Daur, Dongxiang (Santa), Monguor or Chagaan Monggol, Yunnan Mongols, Sichuan Mongols, Sogwo Arig, Yugur and Bonan people in China are considered as descendants of Mongol soldiers, who obeyed their Khaan’s order to safeguard the conquered area and waited in exceptional loyalty. -

Written Evidence Submitted by East Turkistan Government in Exile (XIN0078)

Written evidence submitted by East Turkistan Government in Exile (XIN0078) The East Turkistan Problem and How the UK Should Address it East Turkistan Government in Exile The East Turkistan Government in Exile (ETGE) is the democratically elected official body representing East Turkistan and its people. On September 14, 2004, the government in exile was established in Washington, DC by a coalition of Uyghur and other East Turkistani organizations. The East Turkistan Government in Exile is a democratic body with a representative Parliament. The primary leaders — President, Vice President, Prime Minister, Speaker (Chair) of Parliament, and Deputy Speaker (Chair) of Parliament — are democratically elected by the Parliament members from all over the East Turkistani diaspora in the General Assembly which takes place every four years. The East Turkistan Government in Exile is submitting this evidence and recommendation to the UK Parliament and the UK Government as it is the leading body representing the interests of not only Uyghurs but all peoples of East Turkistan including Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, Uzbeks, and Tatars. More importantly, the ETGE has submitted the first ever legal complaint to the International Criminal Court against China and its officials for genocide and other crimes against humanity. We would like the UK Government to assist our community using all available means to seek justice and end to decades of prolonged colonization, genocide, and occupation in East Turkistan. Brief History of East Turkistan and the Uyghurs With a history of over 6000 years, according to Uyghur historians like Turghun Almas, the Uyghurs are the natives of East Turkistan. Throughout the millennia, the Uyghurs and other Turkic peoples have established and maintained numerous independent kingdoms, states, and even empires. -

Doğu Türkistan Tarihinde Kirgizlarin

T. C. ULUDA Ğ ÜNİVERS İTES İ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENST İTÜSÜ TAR İH ANAB İLİM DALI GENEL TÜRK TAR İHİ BİLİM DALI DO ĞU TÜRK İSTAN TAR İHİNDE KIRGIZLARIN TES İRLER İ (1700-1878 ) (YÜKSEK L İSANS TEZ İ) Abdrasul İSAKOV BURSA 2007 T. C. ULUDA Ğ ÜNİVERS İTES İ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENST İTÜSÜ TAR İH ANAB İLİM DALI GENEL TÜRK TAR İHİ B İLİM DALI DO ĞU TÜRK İSTAN TAR İHİNDE KIRGIZLARIN TES İRLER İ (1700-1878 ) (YÜKSEK L İSANS TEZ İ) Danı şman Yrd. Doç. Dr. Sezai SEV İM Abdrasul İSAKOV BURSA 2007 2 T. C. ULUDA Ğ ÜN İVERS İTES İ SOSYAL B İLİMLER ENST İTÜSÜ MÜDÜRLÜ ĞÜNE Tarih Anabilim Dalı, Genel Türk Tarihi Bilim Dalı’nda 700542005 numaralı Abdrasul İsakov’un hazırladı ğı “Do ğu Türkistan Tarihinde Kırgızların Tesirleri (1700-1878)” konulu Yüksek Lisans Çalı şması ile ilgili tez savunma sınavı, …../…../ 20… günü ……- ………..saatleri arasında yapılmı ş, sorulan sorulara alınan cevaplar sonunda adayın çalı şmasının …………….. oldu ğuna …………… ile karar verilmi ştir. İmza Ba şkan …………………………. İmza İmza Üye (Danı şman)………………………………… Üye………………………………. ....../......./ 20..... 3 ÖZET “Do ğu Türkistan Tarihinde Kırgızların Tesirleri (1700-1878)” isimli yüksek lisans çalı şmasında, 1700-1878 yılları arası Do ğu Türkistan’daki siyasi olaylarda Kırgızların tesirleri ara ştırılmak istenmi ştir. Tez: “Do ğu Türkistan Hakkında Genel Bilgi”, “Do ğu Türkistan’da Baskıncılara Kar şı Mücadeleler”, “Do ğu Türkistan’da Kırgızlar” ve “Do ğu Türkistan’da Yapılan Mücadelelerde Kırgızlar” isimli dört ba şlıktan olu şmu ştur. Birinci bölümde, Sakalar devrinden XVIII. yüzyıla kadarki Do ğu Türkistan’ın kısa tarihi, bölgeyi zapt etmi ş olan Kalmuk ve Mançuların tarih sahnesine çıkmaları, ayrı ayrı ele alınmı ş ve ayrıca hocaların men şei ve Do ğu Türkistan’da iktidara gelmeleri anlatılmaya çalı şılmı ştır. -

Westernisation, Ideology and National Identity in 20Th-Century Chinese Music

Westernisation, Ideology and National Identity in 20th-Century Chinese Music Yiwen Ouyang PhD Thesis Royal Holloway, University of London DECLARATION OF AUTHORSHIP I, Yiwen Ouyang, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: 19 May 2012 I To my newly born baby II ABSTRACT The twentieth century saw the spread of Western art music across the world as Western ideology and values acquired increasing dominance in the global order. How did this process occur in China, what complexities does it display and what are its distinctive features? This thesis aims to provide a detailed and coherent understanding of the Westernisation of Chinese music in the 20th century, focusing on the ever-changing relationship between music and social ideology and the rise and evolution of national identity as expressed in music. This thesis views these issues through three crucial stages: the early period of the 20th century which witnessed the transition of Chinese society from an empire to a republic and included China’s early modernisation; the era from the 1930s to 1940s comprising the Japanese intrusion and the rising of the Communist power; and the decades of economic and social reform from 1978 onwards. The thesis intertwines the concrete analysis of particular pieces of music with social context and demonstrates previously overlooked relationships between these stages. It also seeks to illustrate in the context of the appropriation of Western art music how certain concepts acquired new meanings in their translation from the European to the Chinese context, for example modernity, Marxism, colonialism, nationalism, tradition, liberalism, and so on. -

Controlling Xinjiang: Autonomy on China's “New Frontier”

Controlling Xinjiang: Autonomy on China’s “New Frontier” I. INTRODUCTION II. BACKGROUND A. Chinese Control of Xinjiang: A Brief Political History 1. Early Interactions with Xinjiang 2. Political Integration in the Qing 3. Increased Unrest on the Frontier 4. Liberation B. CCP’S Policy Towards National Minorities 1. The Winding Road Towards “Autonomy” 2. Early Policy: Unify and Conquer: Dangle the Carrot 3. Welcoming Minorities into the Chinese “Family” 4. Creation of the Autonomous Regions III. ANALYSIS A. An Examination of Relevant Laws 1. Introduction 2. Granting Autonomy: “Give and Take” 3. The Law on Regional National Autonomy 4. Does Xinjiang’s Autonomy Meet International Standards? B. Autonomy: A Salve for China’s “Splittist” Headache C. The Party’s Perspective: Stability and Progress IV. CONCLUSION I. INTRODUCTION Along the ancient Silk Road, beyond the crumbling remnants of the Great Wall’s western terminus and the realm of ethnically Han Chinese1 lies Xinjiang: the vast and desolate northwestern province of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and the beginning of Central Asia.2 Strategically located, the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region (XUAR) is a vital component of China’s political and economic stability.3 1 Central Intelligence Agency, World Fact Book, at http://www.cia.gov/cia/publications/factbook (last visited Feb. 8, 2002). Han, the state- recognized majority nationality, comprise approximately 91.9% of China’s almost 1.3 billion people. Id. 2 JACK CHEN, THE SINKIANG STORY xx (1977). Xinjiang covers one-sixth of China’s total land area, and at 660,000 square miles, the province is as big as Britain, France, Germany, and Italy combined. -

The Fight for the Republic in China

The Fight For The Republic In China B.L. Putnam Weale The Fight For The Republic In China Table of Contents The Fight For The Republic In China.....................................................................................................................1 B.L. Putnam Weale........................................................................................................................................1 PREFACE......................................................................................................................................................1 CHAPTER I. GENERAL INTRODUCTION...............................................................................................2 CHAPTER II. THE ENIGMA OF YUAN SHIH−KAI...............................................................................10 CHAPTER III. THE DREAM REPUBLIC.................................................................................................16 CHAPTER IV. THE DICTATOR AT WORK............................................................................................22 CHAPTER V. THE FACTOR OF JAPAN.................................................................................................27 CHAPTER VI. THE TWENTY−ONE DEMANDS...................................................................................33 CHAPTER VII. THE ORIGIN OF THE TWENTY−ONE DEMANDS....................................................50 CHAPTER VIII. THE MONARCHIST PLOT...........................................................................................60 -

Birth of Uyghur National History in Semirech'ye

ORIENTE MODERNO Oriente Moderno 96 (�0�6) �8�-�96 brill.com/ormo Birth of Uyghur National History in Semirech’ye Näzärγoja Abdusemätov and His Historical Works Ablet Kamalov Institute of Oriental Studies and University Turan – Almaty [email protected] Abstract The article discusses the birth of a national historical discourse in Central Asia at the turn of the 20th century with special reference to the Taranchi Turks of Russian Semirech’ye (Zhetissu) and early example of Uyghur national history written by the Taranchi intellectual Näzärγoja Abdusemätov (d. 1951). The article shows how intel- lectuals among the Taranchi Turks, an ethnic group who settled in the Semirech’ye oblast of the Russian Empire in late 19th century, became involved in debates on nations and national history organized on the pages of the Tatar newspapers and jour- nals in the Volga region of Russia. Näzärγoja Abdusemätov’s published work Ili Taranchi Türklirining tarihi (‘History of the Taranchi Turks of Ili’) receives particular attention as part of an examination of the evolution of the author’s ideas about an Uyghur nation. Keywords Semirech’ye – Taranchi Turks – Kazakhstan – Uyghur – National history – Näzärγoja Abdusemätov Introduction As Nationalism studies show, history plays a very important role in shaping ethnic and national identity. The spread of nationalistic discourse in Europe was accompanied by the emergence of an ethnocentric vision on the historical past focusing on the real or imagined past of particular ethnic groups imagined now as a ‘nation’. This new vision on the past contrasted with previous narra- tions of history centred mainly on stories of dynasties, outstanding persons © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, ���6 | doi �0.��63/���386�7-��340099 182 Kamalov (‘history of big men’) or other wealthy people. -

Community Matters in Xinjiang 1880–1949 China Studies

Community Matters in Xinjiang 1880–1949 China Studies Published for the Institute for Chinese Studies University of Oxford Editors Glen Dudbridge Frank Pieke VOLUME 17 Community Matters in Xinjiang 1880–1949 Towards a Historical Anthropology of the Uyghur By Ildikó Bellér-Hann LEIDEN • BOSTON 2008 Cover illustration: Woman baking bread in the missionaries’ home (Box 145, sheet nr. 26. Hanna Anderssons samling). Courtesy of the National Archives of Sweden (Riksarkivet) and The Mission Covenant Church of Sweden (Svenska Missionskyrkan). This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bellér-Hann, Ildikó. Community matters in Xinjiang, 1880–1949 : towards a historical anthropology of the Uyghur / by Ildikó Bellér-Hann. p. cm — (China studies, ISSN 1570–1344 ; v. 17) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-16675-2 (hardback : alk. paper) 1. Uighur (Turkic people)—China— Xinjiang Uygur Zizhiqu—Social life and customs. 2. Uighur (Turkic people)—China— Xinjiang Uygur Zizhiqu—Religion. 3. Muslims—China—Xinjiang Uygur Zizhiqu. 4. Xinjiang Uygur Zizhiqu (China)—Social life and customs. 5. Xinjiang Uygur Zizhiqu (China)—Ethnic relations. 6. Xinjiang Uygur Zizhiqu (China)—History—19th century. I. Title. II. Series. DS731.U4B35 2008 951’.604—dc22 2008018717 ISSN 1570-1344 ISBN 978 90 04 16675 2 Copyright 2008 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. -

Bee Round 3 Bee Round 3 Regulation Questions

NHBB Nationals Bee 2018-2019 Bee Round 3 Bee Round 3 Regulation Questions (1) This man's alleged last words were \The battle is at its height - wear my armor and beat my war drums. Do not announce my death." After his death, this man was given the title Chunmugong. A double agent plot led to the removal of this man in favor of a commander who was decisively defeated at the Battle of Chilchonryang. This man was killed during his final victory at the Battle of Noryang, after he defeated 330 Japanese ships with 13 at the Battle of Myeongnyang. For the point, name this \Nelson of the East", a Korean admiral who championed turtle ships. ANSWER: Yi Sun-Sin (2) A politician with this surname, the rival of Dave Pearce, had an affair with burlesque performer Blaze Starr. The Wall Street Journal, jokingly labeled a politician with this surname the \fourth branch of government" due to the immense power he wielded as chairman of the Senate Finance Committee. That man's father, another politician with this surname, was assassinated by Carl Weiss. The \Share Our Wealth Plan", which called for making \Every Man A King", was formulated by a member of, for the point, what Louisiana political dynasty whose members included Earl, Russell, and Huey? ANSWER: Long (accept Earl Long; accept Russell Long; accept Huey Long) (3) This region's inhabitants launched raids against its northern neighbors, called \harvesting the steppes," to fuel its slave trade, which was based out of Kefe. Haci Giray [ha-ji ge-rai] established this region's namesake khanate after breaking off from the Golden Horde. -

Mpub10110094.Pdf

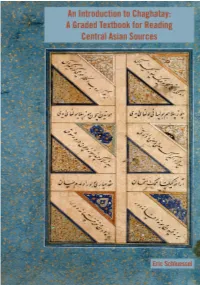

An Introduction to Chaghatay: A Graded Textbook for Reading Central Asian Sources Eric Schluessel Copyright © 2018 by Eric Schluessel Some rights reserved This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, California, 94042, USA. Published in the United States of America by Michigan Publishing Manufactured in the United States of America DOI: 10.3998/mpub.10110094 ISBN 978-1-60785-495-1 (paper) ISBN 978-1-60785-496-8 (e-book) An imprint of Michigan Publishing, Maize Books serves the publishing needs of the University of Michigan community by making high-quality scholarship widely available in print and online. It represents a new model for authors seeking to share their work within and beyond the academy, offering streamlined selection, production, and distribution processes. Maize Books is intended as a complement to more formal modes of publication in a wide range of disciplinary areas. http://www.maizebooks.org Cover Illustration: "Islamic Calligraphy in the Nasta`liq style." (Credit: Wellcome Collection, https://wellcomecollection.org/works/chengwfg/, licensed under CC BY 4.0) Contents Acknowledgments v Introduction vi How to Read the Alphabet xi 1 Basic Word Order and Copular Sentences 1 2 Existence 6 3 Plural, Palatal Harmony, and Case Endings 12 4 People and Questions 20 5 The Present-Future Tense 27 6 Possessive -

These Sources Are Verifiable and Come From

0 General aim: To give institutions a report as unbiased, independent and reliable as possible, in order to raise the quality of the debate and thus the relative political decisions. Specific aims: To circulate this report to mass media and in public fora of various nature (i.e. human rights summits) as well as at the institutional level, with the purpose of enriching the reader’s knowledge and understanding of this region, given its huge implications in the world peace process. As is well known, for some years now highly politicised anti-Chinese propaganda campaigns have targeted the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, often spreading groundless, non-verifiable or outright false information, triggering on these bases a sanctions war and causing serious damage to international relations. There is a dramatic lack of unbiased and alternative documentation on the topic, especially by researchers who have lived and studied in China and Xinjiang. This report aims to fill this gap, by deepening and contextualising the region and its real political, economic and social dynamics, and offering an authoritative and documented point of view vis-à- vis the reports that Western politicians currently have at their disposal. The ultimate goal of this documentation is to promote an informed public debate on the topic and offer policymakers and civil society a different point of view from the biased and specious accusations coming from the Five Eyes countries, the EU and some NGOs and think-tanks. Recently some Swedish researchers have done a great job of deconstructing the main Western allegations about the situation in the autonomous region of Xinjiang.