Bank-Level Analysis of the Determinants of Lending Rate Stickiness in Uganda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bank of Uganda

Status of Financial Inclusion in Uganda First Edition- March 2014 BANK OFi UGANDA Table of Contents List of Abbreviations and Acronyms ..................................................................................................... iii Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................iv 1.0 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 1 2.0 Concept of Financial Inclusion ......................................................................................................... 1 3.0 Financial Inclusion Landscape for Uganda .................................................................................. 4 3.1 Data Sources ...................................................................................................................................... 4 3.2 Demand Side Indicators ................................................................................................................. 5 3.3 Supply Side Indicators .................................................................................................................... 7 3.3.1 Financial Access Indicators .................................................................................................... 7 3.3.2 Comparison of Access Indicators across Countries. ...................................................................... 14 3.3.3 Geographic Indicators -

Crane Bank to Appeal to Supreme Court

Plot 37/43 Kampala Road, P.O. Box 7120 Kampala Cable Address: UGABANK, Telex: 61069/61244 General Lines: (+256-414) 258441/6, 258061/6, 0312-392000 or 0417-302000. Fax: (+256-414) 233818 Website: www.bou.or.ug E-mail: [email protected] CRANE BANK TO APPEAL TO SUPREME COURT KAMPALA – 30 June 2020 – Bank of Uganda (BoU) wishes to inform the public of its decision to appeal the Court of Appeal’s dismissal of the case filed by Crane Bank Limited (in Receivership) vs. Sudhir Ruparelia and Meera Investments Limited to the Supreme Court. In exercise of its powers under sections 87(3), 88(1)(a)&(b) of the Financial Institutions Act, 2004, BoU placed Crane Bank Ltd (In Receivership) [“Crane Bank”] under Statutory Management on 20th October 2016. This decision was necessary upon discovering that Crane Bank had significant and increasing liquidity problems that could not be resolved without the Central Bank’s intervention given that Crane Bank had failed to obtain credit from anywhere else. An inventory by external auditors found that the assets of Crane Bank were significantly less than its liabilities. In order to protect the financial system and prevent loss to the depositors of Crane Bank, Bank of Uganda had to spend public funds to pay Crane Bank’s depositors. A subsequent forensic investigation as to why Crane Bank became insolvent found a number of wrongful and irregular activities linked to Sudhir Ruparelia and Meera Investments Ltd. These findings form the basis of the claims in the lawsuit by Crane Bank. The suit was necessary for recovery of the taxpayers’ money used to pay depositors’ funds as well as the other liabilities of Crane Bank. -

International Directory of Deposit Insurers

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation International Directory of Deposit Insurers September 2015 A listing of addresses of deposit insurers, central banks and other entities involved in deposit insurance functions. Division of Insurance and Research Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation Washington, DC 20429 The FDIC wants to acknowledge the cooperation of all the countries listed, without which the directory’s compilation would not have been possible. Please direct any comments or corrections to: Donna Vogel Division of Insurance and Research, FDIC by phone +1 703 254 0937 or by e-mail [email protected] FDIC INTERNATIONAL DIRECTORY OF DEPOSIT INSURERS ■ SEPTEMBER 2015 2 Table of Contents AFGHANISTAN ......................................................................................................................................6 ALBANIA ...............................................................................................................................................6 ALGERIA ................................................................................................................................................6 ARGENTINA ..........................................................................................................................................6 ARMENIA ..............................................................................................................................................7 AUSTRALIA ............................................................................................................................................7 -

Uganda Country Strategy Paper 2017-2021

AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK GROUP UGANDA COUNTRY STRATEGY PAPER 2017-2021 RDGE/COUG June 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................. iii I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................. 1 II. THE COUNTRY CONTEXT ......................................................................................................... 1 2.1 Political Context ......................................................................................................................................... 1 2.2 Economic Context ...................................................................................................................................... 2 2.3 Social development and Cross-cutting Issues……………………………………………………………….. .............................................. 5 III. STRATEGIC OPTIONS, PORTFOLIO PERFORMANCE AND LESSONS ........................ 7 3.1 Country Strategic Framework .................................................................................................................. 7 3.2 Aid Coordination and Harmonization ...................................................................................................... 8 3.3 Country Challenges & Weaknesses and Opportunities and Strengths ................................................. 8 3.5 Key Findings of the CSP 2011-16 Country Portfolio Performance Review (CPPR) ......................... -

Chased Away and Left to Die

Chased Away and Left to Die How a National Security Approach to Uganda’s National Digital ID Has Led to Wholesale Exclusion of Women and Older Persons ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Publication date: June 8, 2021 Cover photo taken by ISER. An elderly woman having her biometric and biographic details captured by Centenary Bank at a distribution point for the Senior Citizens’ Grant in Kayunga District. Consent was obtained to use this image in our report, advocacy, and associated communications material. Copyright © 2021 by the Center for Human Rights and Global Justice, Initiative for Social and Economic Rights, and Unwanted Witness. All rights reserved. Center for Human Rights and Global Justice New York University School of Law Wilf Hall, 139 MacDougal Street New York, New York 10012 United States of America This report does not necessarily reflect the views of NYU School of Law. Initiative for Social and Economic Rights Plot 60 Valley Drive, Ministers Village Ntinda – Kampala Post Box: 73646, Kampala, Uganda Unwanted Witness Plot 41, Gaddafi Road Opp Law Development Centre Clock Tower Post Box: 71314, Kampala, Uganda 2 Chased Away and Left to Die ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This report is a joint publication by the Digital Welfare State and Human Rights Project at the Center for Human Rights and Global Justice (CHRGJ) based at NYU School of Law in New York City, United States of America, the Initiative for Social and Economic Rights (ISER) and Unwanted Witness (UW), both based in Kampala, Uganda. The report is based on joint research undertaken between November 2020 and May 2021. Work on the report was made possible thanks to support from Omidyar Network and the Open Society Foundations. -

Increasing Access to Finance in Uganda Intro

DEVELOPMENT IMPACT CASE STUDY DFCU BANK INCREASING ACCESS TO FINANCE IN UGANDA INTRO ABOUT NORFUND Norfund is Norway’s Development Finance Institution and our mandate is to support the building of sustainable businesses in poor countries, thereby contributing to economic growth and poverty reduction. Norfund’s strategy is to invest in the sectors and countries in which we can have the greatest impact; where the private sector is weak and access to capital is scarce. We concentrate our investments in sectors that are important drivers of development: Clean Energy, Financial Institutions, and Food and Agribusiness. FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS Financial institutions contribute to economic growth by promoting access to finance, encouraging enterprise growth and innovation. Access to finance tends to lead to higher employment growth, especially among micro, small, and medium enterprises, and also helps to reduce poverty.1 DEVELOPMENT RATIONALE Financial institutions need access to debt and equity for extending loans to clients. Capital helps finance business development, enables banks to develop products and increase their market reach. One of the targets of the Sustain- able Development Goals set by the United Nations is to “strengthen the capacity of domestic financial institutions to encourage and expand access INVESTMENT for all to banking, insurance and financial services”. Access to finance is often NEED more of a constraint for small companies than for large companies. According to the IFC, more than 200 million micro- to medium-sized enterprises in developing economies lack access to affordable financial services and credit. 2 Norfund invests in banks, micro finance providers, and other financial institutions that target SMEs, the retail market and clients that have not previously had access to financial services. -

OECD International Network on Financial Education

OECD International Network on Financial Education Membership lists as at May 2020 Full members ........................................................................................................................ 1 Regular members ................................................................................................................. 3 Associate (full) member ....................................................................................................... 6 Associate (regular) members ............................................................................................... 6 Affiliate members ................................................................................................................. 6 More information about the OECD/INFE is available online at: www.oecd.org/finance/financial-education.htm │ 1 Full members Angola Capital Market Commission Armenia Office of the Financial System Mediator Central Bank Australia Australian Securities and Investments Commission Austria Central Bank of Austria (OeNB) Bangladesh Microcredit Regulatory Authority, Ministry of Finance Belgium Financial Services and Markets Authority Brazil Central Bank of Brazil Securities and Exchange Commission (CVM) Brunei Darussalam Autoriti Monetari Brunei Darussalam Bulgaria Ministry of Finance Canada Financial Consumer Agency of Canada Chile Comisión para el Mercado Financiero China (People’s Republic of) China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission Czech Republic Ministry of Finance Estonia Ministry of Finance Finland Bank -

Downloads/Press Releases/2014/Jul/Closure- Of-Global-Trust-Bank July-25-2014.Pdf (Last Accessed on 20/8/16)

Home of Parliament Watch Uganda LEGAL ASPECTS OF CENTRAL BANKS’ EMERGENCY RESCUE POWERS IN RESPECT OF DISTRESSED BANKS: LESSONS FOR UGANDA FROM THE SOUTH AFRICAN EXPERIENCE 1 POLICY SERIES PAPERS NUMBER 17 OF 2017 2 Published by CEPA P. O. Box 23276, Kampala Email: [email protected] Web site: http://www.parliamentwatch.ug http://www.cepa.or.ug Silver Kayondo1 Citation Kayondo S, (2017). Legal aspects of central banks’ emergency rescue powers in respect of distressed banks: lessons for Uganda from the South African experience; CEPA Policy Series Papers Number 17 of 2017. Kampala (c) CEPA 2017 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means – electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without prior written permission of the publisher. CEPA Policy Series papers are developed and published with the generous grants from Open Society Institute for East Africa. The reproduction or use of this publication for academic or charitable purpose or for purposes of informing public policy is exempted from the restriction. Valuable inputs from Okello Isaac, Programs Associate, CEPA The views expressed in this publication are neither for the Centre for Policy Analysis nor its partners 1 Master of Laws (University of Pretoria, South Africa), Bachelor of Laws (Uganda Christian University, Mukono), Post Graduate Diploma in Legal Practice (Law Development Centre, Kampala). Holder of an Advanced Certificate in International Insolvency and Restructuring under the Auspices of the South African Restructuring and Insolvency Practitioners Association (SARIPA). Advocate of the Courts of Judicature (Uganda). -

Supervision and Regulation of Financial

BANK REGULATION AND SUPERVISION Supervision entails using the laws, regulations and A – Asset Quality: The financial institution assets The Bank also conducts daily market intelligence CONSUMER PROTECTION Bank of Uganda (BoU) regulates, licenses and guidelines to examine and inspect the affairs of including loan and investment portfolio should be to assess any potential threats to the integrity and The Bank of Uganda ensures that consumers of SFIs with the aim of ensuring regulatory supervises financial institutions in Uganda. This is safe and sound. soundness of the financial institution and financial financial services are protected through; compliance, depositors' funds are protected, and M – Management: The Board and Management of done to protect depositors’ funds and to ensure the system. - Issuance of Financial Consumer Protection stability of the individual financial institutions and the financial institution should be ethical, credible safety and stability of the financial system which in Guidelines that stipulate the rights and obligations the financial sector as a whole. and capable. turn enhances and supports economic growth. Bank of Uganda then proposes measures to of consumers of financial services as well as the THE SUPERVISION FRAMEWORK E – Earnings: This aims at ensuring that financial mitigate potential risks that may have been responsibilities of the financial service providers to The supervised financial institutions (SFIs) include Bank of Uganda utilises a Risk Based Supervision institutions are profitable enough to -

USE Annual Report 2019.Pdf

1 ANNUAL REPORT 2019 2 RAISE CAPITAL WITH CORPORATE BONDS. Bonds are loans with much lower interest rates. FOR MORE (0312) 370815/370817 Table of CONTENT 08 Corporate Information 09 About this Report 10 Who we Are 11 Mission, Vision and Core Values 12 Our Issuers 14 Milestones 16 Chairman’s Statement 20 Chief Executive Officer Statement 3 23 Board of Directors RAISE 26 Management Committee 27 2019 Highlights CAPITAL WITH 29 Business Review 34 Information Systems CORPORATE BONDS. 35 Corporate Governance 43 Risk Management Bonds are loans with much lower interest rates. Audited Financial Statements 102 Notice of Annual General Meeting 103 Proxy Form FOR MORE (0312) 370815/370817 Annual Report 2019 List of TABLES 29 Table 1: Equities Trading by Quarter (2019) 30 Table 2: Equities Trading Turnover by listed Issuer (2019) 31 Table 3: Account Opening Table 4: Broker Rankings in terms of transactions 32 executed in the Depository. 33 Table 5: Immobilization Status 4 List of FIGURES 29 Figure 1: Monthly Turnover Trend (2018 - 2019) 30 Figure 2: 2019 USE Market Indices 31 Figure 3: Distribution of SCD Accounts 2019 32 Figure 4: Distribution of SCD Registrars 33 Figure 5: Shares Deposited in SCD www.use.or.ug 5 ACRONYMS Plot 18 Kampala Road Orient Plaza, Plot 6/6A, Kampala Road P. O. Box 7197, Kampala, Uganda P.O.Box 7539, Kampala, Uganda ARC Audit and Risk Committee Tel: 0414- 237898 Fax: 0414 258 263 TEL: 0417-719144/0417-719133 Email: [email protected] EMAIL: [email protected] ATS Automated Trading System Central Depository & Settlement -

Vote:023 Ministry of Science,Technology and Innovation

Vote Performance Report Financial Year 2018/19 Vote:023 Ministry of Science,Technology and Innovation QUARTER 4: Highlights of Vote Performance V1: Summary of Issues in Budget Execution Table V1.1: Overview of Vote Expenditures (UShs Billion) Approved Cashlimits Released Spent by % Budget % Budget % Releases Budget by End Q4 by End Q 4 End Q4 Released Spent Spent Recurrent Wage 2.060 2.060 2.052 1.368 99.6% 66.4% 66.7% Non Wage 29.354 23.028 24.178 25.124 82.4% 85.6% 103.9% Devt. GoU 24.458 21.982 26.587 21.022 108.7% 86.0% 79.1% Ext. Fin. 114.422 69.372 0.000 0.000 0.0% 0.0% 0.0% GoU Total 55.872 47.071 52.816 47.515 94.5% 85.0% 90.0% Total GoU+Ext Fin 170.295 116.443 52.816 47.515 31.0% 27.9% 90.0% (MTEF) Arrears 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.0% 0.0% 0.0% Total Budget 170.295 116.443 52.816 47.515 31.0% 27.9% 90.0% A.I.A Total 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.0% 0.0% 0.0% Grand Total 170.295 116.443 52.816 47.515 31.0% 27.9% 90.0% Total Vote Budget 170.295 116.443 52.816 47.515 31.0% 27.9% 90.0% Excluding Arrears Table V1.2: Releases and Expenditure by Program* Billion Uganda Shillings Approved Released Spent % Budget % Budget %Releases Budget Released Spent Spent Program: 1801 Regulation 4.01 1.69 1.79 42.1% 44.6% 105.9% Program: 1802 Research and Innovation 143.85 15.49 15.57 10.8% 10.8% 100.5% Program: 1803 Science Entreprenuership 4.56 1.66 1.72 36.3% 37.7% 103.9% Program: 1849 General Administration and Planning 17.88 33.99 28.44 190.1% 159.1% 83.7% Total for Vote 170.29 52.82 47.51 31.0% 27.9% 90.0% Matters to note in budget execution 1/64 Vote Performance Report Financial Year 2018/19 Vote:023 Ministry of Science,Technology and Innovation QUARTER 4: Highlights of Vote Performance In Quarter four FY 2018/19, the Ministry received a total of UShs.4,626,604,127 Under Wage, Non- Wage, Gratuity and Development categories of the Budget. -

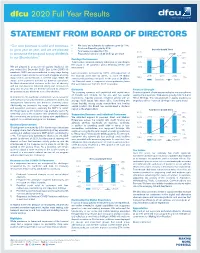

Dfcu 2020 Full Year Results

dfcu 2020 Full Year Results STATEMENT FROM BOARD OF DIRECTORS “Our core business is solid and continues • Net loans and advances to customers grew by 15%. • Customer Deposits grew by 27%. Deposits Growth Trend to grow year on year, and we are pleased • Total assets increased by 18%. 3,515 30% to announce the proposal to pay dividends • Proposed dividend of 50.33 Shillings per share. 27% 2,595 to our Shareholders.” 2,515 20% Earnings Performance 1,979 2,039 Total revenue remained relatively stable year on year despite 1,515 10% the impact of the pandemic and a declining interest rate 3% We are pleased to announce the audited results for the environment. 515 0% year ended 31st December 2020. Due to the COVID-19 0% pandemic, 2020 was unprecedented in many ways having Loan provisions increased by 107% and impairment of an adverse impact across the world and in Uganda affecting the financial asset rose by 400%, to reach 50 Billion 2018 2019 2020 many sectors and livelihoods in different ways. While the (485) -10% consequently posting a net profit for the year of 24 Billion. Deposits% Growth impact of the pandemic affected our business operations, The Financial asset is composed of non-performing loans the Bank demonstrated resilience in the face of adversity that were taken over from the 2017 transaction. and our core business remained strong and continued to grow year on year. We are therefore pleased to announce Dividends Financial Strength the proposal to pay dividends to our Shareholders. The company remained well capitalized with capital ratios Sustained growth of total assets underpins the strength and of 19.34% and 20.94% for tier one and two capital viability of our business.