Never Look Away German Artist Gerhard Richter (B. 1932) May Not

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Never Look Away

NEVER LOOK AWAY An original screenplay by Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck 1. INT. DRESDEN ART MUSEUM – DAY KURT, a small 5-year-old boy with steel grey eyes gazes at the distorted, grimacing faces of soldiers from the hands of Otto Dix, the twisted colors and shapes of Kirchner, Heckel and Schmidt-Rottluff, the bizarre world of Paul Klee. At Kurt's side is his AUNT ELISABETH, an 19 year-old blonde of seductive beauty. They are part of a group of maybe two dozen adults, all ears to a self- confidently eloquent EXHIBITION GUIDE: GUIDE (nodding with regret) Modern art. Yes, ladies and gentlemen. Before the National Socialists took charge, Germany, too, had its share of "modern" art, meaning: something different just about every year - as follows from the word itself. Ironic chuckles from the audience. EXHIBITION GUIDE (CONT'D) But the Germany of National Socialism once again demands a German art which, like the entirety of a nation’s creative values, must be, and shall be, eternal. Bearing no such eternal value for its nation, it can be of no higher value even today. As they stroll past paintings of unconstrained prostitutes, yellow hydrocephalic heads, smirking captains of industry, African-style sculptures… EXHIBITION GUIDE (CONT'D) The German woman is ridiculed and equaled to prostitutes. The paintings appear to confirm this. EXHIBITION GUIDE (CONT'D) The soldier is portrayed either as a murderer or as the victim of senseless slaughter, all this in an attempt to destroy the German people’s deeply rooted respect for a soldier’s bravery. -

Anna Magnani

5 JUL 19 5 SEP 19 1 | 5 JUL 19 - 5 SEP 19 88 LOTHIAN ROAD | FILMHOUSECinema.COM FILMS WORTH TALKING ABOUT HOME OF THE EDINBURGH INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL Filmhouse, Summer 2019, Part II Luckily I referred to the last issue of this publication as the early summer double issue, which gives me the opportunity to call this one THE summer double issue, as once again we’ve been able to cram TWO MONTHS (July and August) of brilliant cinema into its pages. Honestly – and honesty about the films we show is one of the very cornerstones of what we do here at Filmhouse – should it become a decent summer weather-wise, please don’t let it put you off coming to the cinema, for that would be something of an, albeit minor in the grand scheme of things, travesty. Mind you, a quick look at the long-term forecast tells me you’re more likely to be in here hiding from the rain. Honestly…? No, I made that last bit up. I was at a world-renowned film festival on the south coast of France a few weeks back (where the weather was terrible!) seeing a great number of the films that will figure in our upcoming programmes. A good year at that festival invariably augurs well for a good year at this establishment and it’s safe to say 2019 was a very good year. Going some way to proving that statement right off the bat, one of my absolute favourites comes our way on 23 August, Pedro Almodóvar’s Pain and Glory which is simply 113 minutes of cinematic pleasure; and, for you, dear reader, I put myself through the utter bun-fight that was getting to see Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time.. -

Index to Volume 29 January to December 2019 Compiled by Patricia Coward

THE INTERNATIONAL FILM MAGAZINE Index to Volume 29 January to December 2019 Compiled by Patricia Coward How to use this Index The first number after a title refers to the issue month, and the second and subsequent numbers are the page references. Eg: 8:9, 32 (August, page 9 and page 32). THIS IS A SUPPLEMENT TO SIGHT & SOUND SUBJECT INDEX Film review titles are also Akbari, Mania 6:18 Anchors Away 12:44, 46 Korean Film Archive, Seoul 3:8 archives of television material Spielberg’s campaign for four- included and are indicated by Akerman, Chantal 11:47, 92(b) Ancient Law, The 1/2:44, 45; 6:32 Stanley Kubrick 12:32 collected by 11:19 week theatrical release 5:5 (r) after the reference; Akhavan, Desiree 3:95; 6:15 Andersen, Thom 4:81 Library and Archives Richard Billingham 4:44 BAFTA 4:11, to Sue (b) after reference indicates Akin, Fatih 4:19 Anderson, Gillian 12:17 Canada, Ottawa 4:80 Jef Cornelis’s Bruce-Smith 3:5 a book review; Akin, Levan 7:29 Anderson, Laurie 4:13 Library of Congress, Washington documentaries 8:12-3 Awful Truth, The (1937) 9:42, 46 Akingbade, Ayo 8:31 Anderson, Lindsay 9:6 1/2:14; 4:80; 6:81 Josephine Deckers’s Madeline’s Axiom 7:11 A Akinnuoye-Agbaje, Adewale 8:42 Anderson, Paul Thomas Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), Madeline 6:8-9, 66(r) Ayeh, Jaygann 8:22 Abbas, Hiam 1/2:47; 12:35 Akinola, Segun 10:44 1/2:24, 38; 4:25; 11:31, 34 New York 1/2:45; 6:81 Flaherty Seminar 2019, Ayer, David 10:31 Abbasi, Ali Akrami, Jamsheed 11:83 Anderson, Wes 1/2:24, 36; 5:7; 11:6 National Library of Scotland Hamilton 10:14-5 Ayoade, Richard -

Academy Invites 842 to Membership

MEDIA CONTACT [email protected] July 1, 2019 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ACADEMY INVITES 842 TO MEMBERSHIP LOS ANGELES, CA – The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences is extending invitations to join the organization to 842 artists and executives who have distinguished themselves by their contributions to theatrical motion pictures. The 2019 class is 50% women, 29% people of color, and represents 59 countries. Those who accept the invitations will be the only additions to the Academy’s membership in 2019. Six individuals (noted by an asterisk) have been invited to join the Academy by multiple branches. These individuals must select one branch upon accepting membership. New members will be welcomed into the Academy at invitation-only receptions in the fall. The 2019 invitees are: Actors Adewale Akinnuoye-Agbaje – “Suicide Squad,” “Trumbo” Yareli Arizmendi – “A Day without a Mexican,” “Like Water for Chocolate” Claes Bang – “The Girl in the Spider’s Web,” “The Square” Jamie Bell – “Rocketman,” “Billy Elliot” Bob Bergen – “The Secret Life of Pets,” “WALL-E” Bruno Bichir – “Crónica de un Desayuno,” “Principio y Fin” Claire Bloom – “The King’s Speech,” “Limelight” Héctor Bonilla – “7:19 La Hora del Temblor,” “Rojo Amanecer” Juan Diego Botto – “Ismael,” “Vete de Mí” Sterling K. Brown – “Black Panther,” “Marshall” Gemma Chan – “Crazy Rich Asians,” “Mary Queen of Scots” Rosalind Chao – “I Am Sam,” “The Joy Luck Club” Camille Cottin – “Larguées,” “Allied” Kenneth Cranham – “Maleficent,” “Layer Cake” Marina de Tavira – “Roma,” “La Zona (The -

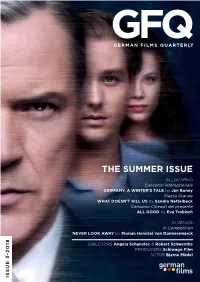

The Summer Issue

GFQ3_18_Druckvorlage.qxp_Layout 1 25.07.18 14:47 Seite 1 GFQ GERMAN FILMS QUARTERLY THE SUMMER ISSUE IN LOCARNO Concorso internazionale GERMANY. A WINTER’S TALE by Jan Bonny Piazza Grande WHAT DOESN’T KILL US by Sandra Nettelbeck Concorso Cineasti del presente ALL GOOD by Eva Trobisch IN VENICE In Competition NEVER LOOK AWAY by Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck DIRECTORS Angela Schanelec & Robert Schwentke PRODUCERS Schiwago Film ACTOR Bjarne Mädel ISSUE 3-2018 GFQ3_18_Druckvorlage.qxp_Layout 1 25.07.18 14:47 Seite 2 CONTENTS GFQ 3-2018 18 20 23 24 26 28 29 30 32 35 36 36 2 GFQ3_18_Druckvorlage.qxp_Layout 1 25.07.18 14:47 Seite 3 GFQ 3-2018 CONTENTS IN THIS ISSUE PORTRAITS NEW DOCUMENTARIES LIFE IN THE TIME OF NO BELONGING DEFENDER OF THE FAITH A portrait of director Angela Schanelec .......................................... 4 Christoph Röhl ................................................................................. 34 AT HOME IN TWO WORLDS DIE GEHEIMNISSE DES SCHÖNEN LEO A portrait of director Robert Schwentke ......................................... 6 THE SECRETS OF HANDSOME LEO Benedikt Schwarzer .............. 34 HANDS ON PRODUCERS STILLER KAMERAD A portrait of Schiwago Film .............................................................. 8 SILENT COMRADE Leonhard Hollmann .......................................... 35 IN SEARCH OF NEW CHALLENGES SUNSET OVER MULHOLLAND DRIVE A portrait of actor Bjarne Mädel ....................................................... 10 Uli Gaulke ......................................................................................... -

Film Calendar February 8 - April 4, 2019

FILM CALENDAR FEBRUARY 8 - APRIL 4, 2019 TRANSIT A Christian Petzold Film Opens March 15 Chicago’s Year-Round Film Festival 3733 N. Southport Avenue, Chicago www.musicboxtheatre.com 773.871.6607 CATVIDEOFEST RUBEN BRANDT, THE FILMS OF CHRISTIAN PETZOLD IDA LUPINO’S FEBRUARY COLLECTOR HARMONY KORINE MATINEE SERIES THE HITCH-HIKER 16, 17 & 19 OPENS MARCH 1 MARCH 15-21 WEEKENDS AT 11:30AM MARCH 4 AT 7PM Welcome TO THE MUSIC BOX THEATRE! FEATURE FILMS 4 COLD WAR NOW PLAYING 4 OSCAR-NOMINATED DOC SHORTS OPENS FEBRUARY 8 6 AMONG WOLVES FEBRUARY 8-14 6 NEVER LOOK AWAY OPENS FEBRUARY 15 8 AUDITION FEBRUARY 15 & 16 9 LORDS OF CHAOS OPENS FEBRUARY 22 9 RUBEN BRANDT, COLLECTOR OPENS MARCH 1 11 BIRDS OF PASSAGE OPENS MARCH 8 FILM SCHOOL DEDICATED 12 TRANSIT OPENS MARCH 15 The World’s Only 17 WOMAN AT WAR OPENS MARCH 22 TO COMEDY 18 COMMENTARY SERIES Comedy Theory. Storytelling. Filmmaking. Industry Leader Masterclasses. 24 CLASSIC MATINEES Come make history with us. RamisFilmSchool.com 26 CHICAGO FILM SOCIETY 28 SILENT CINEMA 30 MIDNIGHTS SPECIAL EVENTS 7 VALENTINE’S DAY: CASABLANCA FEBRUARY 10 VALENTINE’S DAY: THE PRINCESS BRIDE FEBRUARY 13 & 14 8 CAT VIDEO FEST FEBRUARY 16, 17 & 19 10 JEWISH FILM FESTIVAL MARCH 1-17 10 THE HITCH-HIKER MARCH 4 11 PARTS OF SPEECH: HARI KUNZRU MARCH 12 14 HARMONY KORINE FILM SERIES MARCH 15-21 17 DECONSTRUCTING THE BEATLES MARCH 30 & APRIL 3 Brian Andreotti, Director of Programming VOLUME 37 ISSUE 154 Ryan Oestreich, General Manager Copyright 2019 Southport Music Box Corp. -

Venice / Toronto 2021

I’M YOUR MAN by Maria Schrader TOUBAB by Florian Dietrich HOW TO PLEASE A WOMAN by Renée Webster DIABOLIK by Manetti Bros. THE FORGER by Maggie Peren IN A LAND THAT NO LONGER EXISTS by Aelrun Goette MY SON by Lena Stahl IT’S JUST A PHASE, HONEY by Florian Gallenberger YOU WILL NOT HAVE MY HATE by Kilian Riedhof TUESDAY CLUB by Annika Appelin AMERICA by Ofir Raul Graizer MY NEIGHBOR ADOLF by Leon Prudovsky BETA CINEMA VENICE / TORONTO 2021 LAND OF DREAMS by Shirin Neshat & Shoja Azari THE ODD-JOB MEN by Neus Ballús HINTERLAND by Stefan Ruzowitzky CONTENT 10 " FRESH AND LIGHT-HEARTED. OFFICIAL SELECTION – VENICE ORIZZONTI EXTRA " LAND OF DREAMS by Shirin Neshat and Shoja Azari .............................................................................................................................................................................................................................. Page 06 FILMUFORIA OFFICIAL SELECTION – TIFF THE ODD-JOB MEN by Neus Ballús ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� Page 10 I’M YOUR MAN by Maria Schrader �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� -

THE KANGAROO CHRONICLES by Dani Levy 8 CONTENT OFFICIAL SELECTION - VENICE ORIZZONTI

BERLIN ALEXANDERPLATZ by Burhan Qurbani MY LITTLE SISTER by Stéphanie Chuat & Véronique Reymond NARCISSUS AND GOLDMUND by Stefan Ruzowitzky MY NEIGHBOR ADOLF by Leon Prudovsky HINTERLAND by Stefan HELLO AGAIN - A WEDDING A DAY by Maggie Peren DIABOLIK by Manetti Bros. THE BIKE THIEF by Matt Chambers BETA CINEMA VENICE / TORONTO 2020 NOWHERE SPECIAL by Uberto Pasolini KARNAWAL by Juan Pablo Félix KINDRED by Joe Marcantonio THE AUSCHWITZ REPORT by Peter Bebjak THE KANGAROO CHRONICLES by Dani Levy 8 CONTENT OFFICIAL SELECTION - VENICE ORIZZONTI NOWHERE SPECIAL by Uberto Pasolini ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................. Page 04 OFFICIAL SELECTION - TIFF INDUSTRY SELECTS KARNAWAL by Juan Pablo Félix ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ Page 08 CURRENT LINE-UP KINDRED by Joe Marcantonio ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. Page 12 THE AUSCHWITZ REPORT by Peter Bebjak ........................................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Acclaimed Film `Never Look Away' Showing at Orinda and Rheem

LAMORINDA WEEKLY | Acclaimed film `Never Look Away' showing at Orinda and Rheem Published May 15th, 2019 Acclaimed film `Never Look Away' showing at Orinda and Rheem By Sophie Braccini The movie being shown as part of the International Film Showcase this month is certainly one of the best of the year - one to remember, one to savor, like a work of art. "Never Look Away" is a historical saga developing over a large part of the 20th century, rich in emotions, reflections, metaphors. The film can be cruel; it shows humanity at its worst and its best. It is a story of courage, of memories and is a tribute to the power of art that can transcend lies and reach the core of the human heart. It was inspired by actual stories. A 2018 German film by Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck, who won the 2006 Oscar with "The Lives of Others," "Never Look Away" was nominated for a Golden Globe and for two Academy Awards in the Best Foreign Language Film and Best Cinematography categories. It is a drama where one of the central characters is an incarnation of rational evil that collides with a wonderfully powerful love story. Von Donnersmarck does not hesitate to humorously describe the world of art either, whether it is formulated by a communist party or led by the extravagance of the avant-garde. The film starts in 1931 Germany and follows two families during 30 of the most turbulent years in Europe. Dresden, where the movie is first situated, is a rather prosperous German city that readily succumbs to the fascination of the Third Reich, is turned into rubble at the end of the Second World War, before being stifled by the communist ideology that reigned over East Germany. -

91St Annual Academy Awards® Oscar® Nominations Fact

91ST ANNUAL ACADEMY AWARDS® OSCAR® NOMINATIONS FACT SHEET Best Motion Picture of the Year: Black Panther (Walt Disney) - Kevin Feige, producer - This is his first nomination. BlacKkKlansman (Focus Features) - Sean McKittrick, Jason Blum, Raymond Mansfield, Jordan Peele and Spike Lee, producers - This is the second Best Picture nomination for both Sean McKittrick and Jordan Peele, who were nominated last year for Get Out. This is the third Best Picture nomination for Jason Blum, who was nominated for Whiplash (2014) and last year's Get Out. This is the first Best Picture nomination for both Raymond Mansfield and Spike Lee. Bohemian Rhapsody (20th Century Fox) - Graham King, producer - This is his fourth Best Picture nomination. He was previously nominated for The Aviator (2004) and Hugo (2011), and won the award in 2006 for The Departed. The Favourite (Fox Searchlight) - Ceci Dempsey, Ed Guiney, Lee Magiday and Yorgos Lanthimos, producers - This is the first Best Picture nomination for Ceci Dempsey, Lee Magiday and Yorgos Lanthimos. This is the second Best Picture nomination for Ed Guiney, who was nominated in 2015 for Room. Green Book (Universal) - Jim Burke, Charles B. Wessler, Brian Currie, Peter Farrelly and Nick Vallelonga, producers - This is the second Best Picture nomination for Jim Burke, who was previously nominated for The Descendants (2011). This is the first Best Picture nomination for Charles B. Wessler, Brian Currie, Peter Farrelly and Nick Vallelonga. Roma (Netflix) - Gabriela Rodríguez and Alfonso Cuarón, producers - This is the first nomination for Gabriela Rodríguez. This is the second Best Picture nomination for Alfonso Cuarón, who was nominated in 2013 for Gravity. -

The Summer Issue

GFQ GERMAN FILMS QUARTERLY THE SUMMER ISSUE NEW GERMAN FILMS IN LOCARNO, VENICE, TORONTO & SAN SEBASTIAN DIRECTORS Karin Jurschick & Marco Kreuzpaintner PRODUCER Felix von Boehm of Lupa Film ISSUE 3-2019 ACTRESS Anne Ratte-Polle CONTENTS GFQ 3-2019 16 18 20 21 22 23 25 26 27 29 30 33 2 GFQ 3-2019 CONTENTS IN THIS ISSUE PORTRAITS NEW DOCUMENTARIES PRACTICING POLITICAL DOCUMENTARY ANOTHER REALITY A portrait of director Karin Jurschick .............................................. 4 Noël Dernesch, Olli Waldhauer ...................................................... 30 “MY WORKSPACE IS MY HAPPY PLACE” B.B. UND DIE SCHULE AM FLUSS A portrait of director Marco Kreuzpaintner ...................................... 6 B.B. AND THE SCHOOL BY THE RIVER Detlev F. Neufert .............................................................................. 30 REMAINING INDEPENDENT A portrait of production company Lupa Film ................................. 8 INTERTANGO – EINE VERBINDUNG FÜRS LEBEN INTERTANGO – A CONNECTION FOR LIFE A WOMAN OF MANY TALENTS Hanne Weyh .................................................................................. 31 A portrait of actress Anne Ratte-Polle ............................................ 10 MATERA. VERBORGENE HEIMAT MATERA. MOTHER OF STONE NEWS & NOTES ................................................................................ 12 Alessandro Soetje ............................................................................ 31 NEW FEATURES NEW SHORTS 7500 BOJE Andreas Cordes, Robert Köhler ............................................ -

Going to the Dogs

FABIAN GOING TO THE DOGS FABIAN GOING TO THE DOGS GERMANY / 2021 / 176 Minutes INDEX Synopsis...........................................................................................................................3 Press Notes......................................................................................................................4 Storyline...........................................................................................................................5 Director’s Statement…...………………………………………………………………………………………...….6 "Fabian, our Contemporary World" by Hernán D. Caro.................................................10 Biography Dominik Graf..................................................................................................12 Biography Tom Schilling..................................................................................................12 Biography Albrecht Schuch.............................................................................................13 Biography Saskia Rosendahl............................................................................................14 Credits.............................................................................................................................15 Contact............................................................................................................................16 2 SYNOPSIS Berlin, 1931. Jakob Fabian works in the advertising department of a cigarette factory during the day and drifts through bars, brothels and artist