Augustinian Learning in a Technological World: Social and Emotional Applications

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Impact of the Roman Army (200 BC – AD 476)

Impact of Empire 6 IMEM-6-deBlois_CS2.indd i 5-4-2007 8:35:52 Impact of Empire Editorial Board of the series Impact of Empire (= Management Team of the Network Impact of Empire) Lukas de Blois, Angelos Chaniotis Ségolène Demougin, Olivier Hekster, Gerda de Kleijn Luuk de Ligt, Elio Lo Cascio, Michael Peachin John Rich, and Christian Witschel Executive Secretariat of the Series and the Network Lukas de Blois, Olivier Hekster Gerda de Kleijn and John Rich Radboud University of Nijmegen, Erasmusplein 1, P.O. Box 9103, 6500 HD Nijmegen, The Netherlands E-mail addresses: [email protected] and [email protected] Academic Board of the International Network Impact of Empire geza alföldy – stéphane benoist – anthony birley christer bruun – john drinkwater – werner eck – peter funke andrea giardina – johannes hahn – fik meijer – onno van nijf marie-thérèse raepsaet-charlier – john richardson bert van der spek – richard talbert – willem zwalve VOLUME 6 IMEM-6-deBlois_CS2.indd ii 5-4-2007 8:35:52 The Impact of the Roman Army (200 BC – AD 476) Economic, Social, Political, Religious and Cultural Aspects Proceedings of the Sixth Workshop of the International Network Impact of Empire (Roman Empire, 200 B.C. – A.D. 476) Capri, March 29 – April 2, 2005 Edited by Lukas de Blois & Elio Lo Cascio With the Aid of Olivier Hekster & Gerda de Kleijn LEIDEN • BOSTON 2007 This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC-BY-NC 4.0 License, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. -

Theologians As Persons in Dante's Commedia Abigail Rowson

Theologians as Persons in Dante’s Commedia Abigail Rowson Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Leeds School of Languages, Cultures and Societies January 2018 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. The right of Abigail Rowson to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by Abigail Rowson in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. 2 Acknowledgements Firstly, I am indebted to my supervisors, Claire Honess and Matthew Treherne, whose encouragement and support at the outset of this project gave me the confidence to even attempt it. I hope this work repays at least some of the significant amount of trust they placed in me; they should know that I shall be forever grateful to them. Secondly, this thesis would not have taken the shape it has without some wonderful intellectual interlocutors, including the other members of the Leeds/Warwick AHRC project. I feel fortunate to have been part of this wider intellectual community and have benefited enormously by being one of a team. I began to develop the structure and argument of the thesis at the University of Notre Dame’s Summer Seminar on Dante’s Theology, held at Tantur Ecumenical Institute, Jerusalem, 2013. The serendipitous timing of this event brought me into contact with an inspirational group of Dante scholars and theologians, whose generosity and intellectual humility was the hallmark of the fortnight. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

SMATHERS LIBRARIES’ LATIN AND GREEK RARE BOOKS COLLECTION UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2016 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS page LECTORI: TO THE READER ........................................................................................ 20 LATIN AUTHORS.......................................................................................................... 24 Ammianus ............................................................................................................... 24 Title: Rerum gestarum quae extant, libri XIV-XXXI. What exists of the Histories, books 14-31. ................................................................................. 24 Apuleius .................................................................................................................. 24 Title: Opera. Works. ......................................................................................... 24 Title: L. Apuleii Madaurensis Opera omnia quae exstant. All works of L. Apuleius of Madaurus which are extant. ....................................................... 25 See also PA6207 .A2 1825a ............................................................................ 26 Augustine ................................................................................................................ 26 Title: De Civitate Dei Libri XXII. 22 Books about the City of God. ..................... 26 Title: Commentarii in Omnes Divi Pauli Epistolas. Commentary on All the Letters of Saint Paul. .................................................................................... -

Titus Quinctius Flamininus, the Man and His Portrayal by Plutarch

for my father Promotor Prof. dr. Kristoffel Demoen Vakgroep Letterkunde Copromotor dr. Koen De Temmerman Vakgroep Letterkunde Decaan Prof. dr. Freddy Mortier Rector Prof. dr. Paul Van Cauwenberge Illustration on cover: gold stater bearing the image of Flamininus, now on display in the British Museum. On the reverse side: image of Nike and identification of the Roman statesman (“T. Quincti”) © Trustees of the British Museum. Alle rechten voorbehouden. Niets uit deze uitgave mag worden verveelvoudigd, opgeslagen in een geautomatiseerd gegevensbestand, of openbaar gemaakt, in enige vorm of op enige wijze, hetzij elektronisch, mechanisch, door fotokopieën, opnamen, of enige andere manier, zonder voorafgaande toestemming van de uitgever. Faculteit Letteren & Wijsbegeerte Peter Newey Titus Quinctius Flamininus, the Man and his Portrayal by Plutarch Proefschrift voorgedragen tot het behalen van de graad van Doctor in de Taal- en Letterkunde 2012 Foreword It was nearly fifty years ago as an undergraduate that, following a course of lectures on Livy XXXIII, I first met Titus Quinctius Flamininus. Fascinated by the inextricable blend of historicity and personality that emerges from Livy‖s text, I immediately directed my attention toward Polybius 18. Plutarch‖s Life of Flamininus was the next logical step. Although I was not destined to pursue an academic career, the deep impression left on me by these authors endured over the following years. Hence, finally, with the leisure and a most gratefully accepted opportunity, my thesis. My thanks are due initially to Dr T.A. Dorey, who inspired and nurtured my interest in ancient historiography during my undergraduate years in the University of Birmingham. -

Carthage and Tunis, the Old and New Gates of the Orient

^L ' V •.'• V/ m^s^ ^.oF-CA < Viiiiiiiii^Tv CElij-^ frt ^ Cci Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2008 with funding from < IVIicrosoft Corporation f.]IIBR, -^'.^ ;>J0^ r\f •lALIFOff^/, =3 %WJ. # >? slad. http://www.archive.org/details/carthagetunisold(Jl :hhv ^i. I)NIVER% ^ylOSMElfr^^ >^?S(f •Mmv^ '''/iawiNMW^ J ;; ;ijr{v'j,!j I ir^iiiu*- ^AUii ^^WEUNIVERS/, INJCV '"MIFO/?^ ^5WrUNIVER% CARTHAGE AND TUNIS VOL. 1 Carthaginian vase [Delattre). CARTHAGE AND TUNIS THE OLD AND NEfF GATES OF THE ORIENT By DOUGLAS SLADEN Author of "The Japs at Home," "Queer Things about Japan," *' In Sicily," etc., etc. ^ # ^ WITH 6 MAPS AND 68 ILLUSTRATIONS INCLUDING SIX COLOURED PLATES By BENTON FLETCHER Vol. I London UTCHINSON & CO. ternoster Row # 4» 1906 Carthaginian razors [Delatire). or V. J DeDicateO to J. I. S. WHITAKER, F.Z.S., M.B.O.U. OF MALFITANO, PALERMO AUTHOR OF " THE BIRDS OF TUNISIA " IN REMEMBRANCE OF REPEATED KINDNESSES EXTENDING OVER A PERIOD OF TEN YEARS 941029 (zr Carthaginian writing (Delattre). PREFACE CARTHAGE and Tunis are the Gates of the Orient, old and new. The rich wares of the East found their way into the Mediterranean in the galleys of Carthage, the Venice of antiquity ; and though her great seaport, the Lake of Tunis, is no longer seething with the commerce of the world, you have only to pass through Tunis's old sea-gate to find yourself surrounded by the people of the Bible, the Arabian Nights, and the Alhambra of the days of the Moors. Carthage was the gate of Eastern commerce, Tunis is the gate of Eastern life. -

African Art at the Portuguese Court, C. 1450-1521

African Art at the Portuguese Court, c. 1450-1521 By Mario Pereira A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History of Art and Architecture at Brown University Providence, Rhode Island May 2010 © Copyright 2010 by Mario Pereira VITA Mario Pereira was born in Boston, Massachusetts in 1973. He received a B.A. in Art History from Oberlin College in 1996 and a M.A. in Art History from the University of Chicago in 1997. His master’s thesis, “The Accademia degli Oziosi: Spanish Power and Neapolitan Culture in Southern Italy, c. 1600-50,” was written under the supervision of Ingrid D. Rowland and Thomas Cummins. Before coming to Brown, Mario worked as a free-lance editor for La Rivista dei Libri and served on the editorial staff of the New York Review of Books. He also worked on the curatorial staff of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum where he translated the exhibition catalogue Raphael, Cellini and a Renaissance Banker: The Patronage of Bindo Altoviti (Milan: Electa, 2003) and curated the exhibition Off the Wall: New Perspectives on Early Italian Art in the Gardner Museum (2004). While at Brown, Mario has received financial support from the Graduate School, the Department of History of Art and Architecture, and the Program in Renaissance and Early Modern Studies. From 2005-2006, he worked in the Department of Prints, Drawings and Photographs at the Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design. In 2007-2008, he received the J. M. Stuart Fellowship from the John Carter Brown Library and was the recipient of an Andrew W. -

IFRIQAYA Notes for a Tour of Northern Africa in September-October 2011

IFRIQAYA notes for a tour of northern Africa in September-October 2011 Miles Lewis Cover illustration: the Castellum of Kaoua. Gsell, Monuments Antiques, I, p 105. CONTENTS Preamble 5 History 6 Modern Algeria 45 Modern Tunisia 58 Modern Libya 65 Timeline 65 Pre-Roman Architecture 72 Greek & Roman Architecture 75 Christian Architecture 87 Islamic Architecture 98 Islamic and Vernacular Building Types 100 Pisé and Concrete 102 The Entablature and Dosseret Block 104 Reconstruction of the Classical Language 107 LIBYA day 1: Benghazi 109 day 2: the Pentapolis 110 day 3: Sabratha 118 day 4: Lepcis Magna & the Villa Sileen 123 day 5: Ghadames 141 day 6: Nalut, Kabaw, Qasr-el-Haj 142 day 7: Tripoli 144 TUNISIA day 8: Tunis & Carthage 150 day 9: the Matmata Plateau 160 day 10: Sbeitla; Kairouan 167 day 11: El Jem 181 day 12: Cap Bon; Kerkouane 184 day 13: rest day – options 187 day 14: Thuburbo Majus; Dougga 190 day 15: Chemtou; Bulla Regia; Tabarka 199 ALGERIA day 16: Ain Drahram; cross to Algeria; Hippo 201 day 17: Hippo; Tiddis; Constantine 207 day 18: Tébessa 209 day 19: Timgad; Lambaesis 214 day 20: Djémila 229 day 21: Algiers 240 day 22: Tipasa & Cherchell 243 day 23: Tlemcen 252 Ifriqaya 5 PREAMBLE This trip is structured about but by no means confined to Roman sites in North Africa, specifically today’s Libya, Tunisia and Algeria. But we look also at the vernacular, the Carthaginian, the Byzantine and the early Islamic in the same region. In the event the war in Libya has forced us to omit that country from the current excursion, though the notes remain here. -

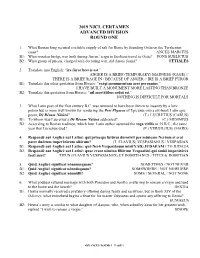

2019 Njcl Certamen Advanced Division Round One

2019 NJCL CERTAMEN ADVANCED DIVISION ROUND ONE 1. What Roman king secured a reliable supply of salt for Rome by founding Ostia on the Tyrrhenian coast? ANCUS MARCIUS B1: What wooden bridge was built during Ancus’ reign to facilitate travel to Ostia? PONS SUBLICIUS B2: What group of priests, charged with declaring war, did Ancus found? FĒTIĀLĒS 2. Translate into English: “īra fūror brevis est.” ANGER IS A BRIEF (TEMPORARY) MADNESS (RAGE) // THERE IS A BRIEF RAGE IN / BECAUSE OF ANGER // IRE IS A BRIEF FUROR B1: Translate this other quotation from Horace: “exēgī monumentum aere perennius.” I HAVE BUILT A MONUMENT MORE LASTING THAN BRONZE B2: Translate this quotation from Horace: “nīl mortālibus arduī est.” NOTHING IS DIFFICULT FOR MORTALS 3. What Latin poet of the first century B.C. was rumored to have been driven to insanity by a love potion but is more well known for rendering the Peri Physeos of Epicurus into a six-book Latin epic poem, Dē Rērum Nātūrā? (T.) LUCRETIUS (CARUS) B1: To whom was Lucretius’s Dē Rērum Nātūrā addressed? (C.) MEMMIUS B2: According to Roman tradition, which later Latin author assumed the toga virīlis in 55 B.C., the same year that Lucretius died? (P.) VERGIL(IUS) (MARO) 4. Respondē aut Anglicē aut Latīnē: quī prīnceps futūrus dormīvit per mūsicam Nerōnis et erat pater duōrum imperātōrum aliōrum? (T. FLAVIUS) VESPASIANUS / VESPASIAN B1: Respondē aut Anglicē aut Latine: quō Nerō Vespasiānum mīsit?(AD) JUDAEAM / TO JUDAEA B2: Respondē aut Anglicē aut Latīnē: quae erant nōmina fīliōrum Vespasiānī quī ambō imperātōrēs factī sunt? TITUS (FLAVIUS VESPASIANUS) ET DOMITIANUS / TITUS & DOMITIAN 5. -

The Ancient History of the Egyptians, Carthaginians, Assyrians, Babylonians, Medes and Persians, Macedonians and Grecians (Vol

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Ancient History of the Egyptians, Carthaginians, Assyrians, Babylonians, Medes and Persians, Macedonians and Grecians (Vol. 1 of 6) by Charles Rollin This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: The Ancient History of the Egyptians, Carthaginians, Assyrians, Babylonians, Medes and Persians, Macedonians and Grecians (Vol. 1 of 6) Author: Charles Rollin Release Date: April 11, 2009 [Ebook 28558] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE ANCIENT HISTORY OF THE EGYPTIANS, CARTHAGINIANS, ASSYRIANS, BABYLONIANS, MEDES AND PER- SIANS, MACEDONIANS AND GRECIANS (VOL. 1 OF 6)*** The Ancient History Of The Egyptians, Carthaginians, Assyrians, Babylonians, Medes and Persians, Macedonians and Grecians By Charles Rollin Late Principal of the University of Paris Professor of Eloquence in The Royal College And Member of the Royal Academy Of Inscriptions and Belles Letters Translated From The French In Six Volumes Vol. I. New Edition Illustrated With Maps and Other Engravings London Printed for Longman And Co., J. M. Richardson, Hamilton And Co., Hatchard And Son, Simpkin And Co., Rivingtons, Whittaker And Co., Allen And Co., Nisbet And Co., J. Bain, T. And W. Boone, E. Hodgson, T. Bumpus, Smith, Elder, And Co., J. Capes, L. Booth, Bigg And Son, Houlston And Co., H. Washbourne, Bickets And Bush, Waller And Son, Cambridge, Wilson And Sons, York, G. -

Carthage and Roman North Africa Page 1 of 152

Carthage and Roman North Africa Page 1 of 152 Carthage and Roman North Africa Hannibal’s army crossing the Alps ALRI History 303 Spring Semester 2011 Instructor: Tom Wukitsch Carthage and Roman North Africa Page 2 of 152 Table of Contents Page 3 Introductory notes 4 I -- Autochthons – prehistory 6 I, a – 1 Aterian Industry 12 2 Capsian culture 13 I. b – Early modern homo sapiens 19 I, c – Species differentiation 22 I, d – Berbers 30 II – Carthage 46 III – Carthage history 61 IV – Punic military forces 66 V – Religion in Carthage 71 VI – Punic Wars 72 VI, a – First Punic War 84 VI, b – Interval between 1st and 2nd Punic Wars – Mercenary War 86 VI, c – Second Punic War 107 VI, d --Third Punic War 112 VII – Jugurtha 116 VIII – Africa as a Roman province 127 IX – Christian North Africa 127 IX, a – Christian Carthage 132 IX, b – Augustine of Hippo 137 IX, c – Vandals 144 IX, d – Reconquest 146 X – Tunisia Archeology Carthage and Roman North Africa Page 3 of 152 Introductory Notes: Spelling: The spelling of personal and place names of the Carthaginians (Phoenicians) is only a matter of convention. Our sources are Greek, Roman, and Semitic and involve transliterations among three alphabets, all of which have changed from their ancient forms. This is further complicated by the fact that modern scholarly research and publication has been carried out in several modern languages (mostly French, Italian, Spanish, English [British and American versions), German, Greek, and Arabic with a smattering of others, e.g., Polish) all of which have their own spelling idiosyncracies. -

Ancient World.Indb

T C Publisher’s Note v Contributors xix Editor’s Introduction ix List of Maps liii Key to Pronunciation xvii V 1 A N E O Ancient Near East Government 5 The Ancient Warka (Uruk) 67 Ancient Near East Literature 10 Ancient Near East Trade 72 Ancient Near East Science 17 Ancient Near East Warfare 77 Ancient Near East City Life 24 Ancient Near East Women 84 Ancient Near East Country Life 29 Ancient Near East Royals 89 Ancient Near East Food & Agriculture 34 Ancient Near East Artists 93 Ancient Near East Family Life 39 Egyptian Soldiers 97 The Hurrian People 44 Near Eastern Soldiers 101 The Mamluks 50 Ancient Near East Tradesmen 105 The Sāsānid Empire 54 Ancient Near East Scribes 109 The Kassites 61 Ancient Near East Slaves 113 P, P E ‘Abd Allāh ibn al-’Abbās 119 Arameans 131 ‘Abd Allāh ibn az-Zubayr 119 Ardashīr I 132 ‘Abd Allāh ibn Sa‘d ibn Abī Sarḥ 120 Argishti I 133 ‘Abd al-Malik 120 Armenia 133 Abraha 121 Arsacid dynasty 135 Abū Bakr 121 Artabanus I-V 135 Achaemenian dynasty 122 Artavasdes II of Armenia 136 Ahab 123 Artemisia I 136 ‘Ā’ishah bint Abī Bakr 124 Artemisia II 137 Akiba ben Joseph 124 Astyages 137 ‘Alī ibn Abī Ṭ ālib 125 Atossa 138 Amos 125 Attalid dynasty 139 ‘Amr ibn al-‘Āṣ Mosque 126 Avesta 140 Anatolia 126 Bar Kokhba 141 Aqhat epic 128 Bathsheba 141 Arabia 129 Ben-Hadad I 142 xxxiii AAncientncient WWorld.indborld.indb xxxxiiixxiii 112/12/20162/12/2016 99:34:28:34:28 AAMM xxxiv • Table of Contents Bible: Jewish 142 Kaska 184 Canaanites 144 Labarnas I 185 Christianity 145 Luwians 185 Croesus 148 Lycia 186 Cyaxares 148 Lydia -

Martyrdom and Nationhood in Seventeenth-Century Drama" (2011)

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2011 Sacrificial Acts: Martyrdom and Nationhood in Seventeenth- Century Drama Kelley Kay Hogue Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Hogue, Kelley Kay, "Sacrificial Acts: Martyrdom and Nationhood in Seventeenth-Century Drama" (2011). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 139. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/139 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SACRIFICIAL ACTS: MARTYRDOM AND NATIONHOOD IN SEVENTEENTH- CENTURY DRAMA A Dissertation presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Deparment of English The University of Mississippi By KELLEY KAY HOGUE May 2011 Copyright Kelley Kay Hogue 2011 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT Sacrificial Acts: Martyrdom and Nationhood in Seventeenth-Century Drama posits that the importance of sixteenth-century martyrologies in defining England’s national identity extends to the seventeenth century through popular representations of martyrdom on the page and stage. I argue that drama functions as a gateway between religious and secular conceptions of martyrdom; thus, this dissertation charts the transformation of martyrological narratives from early modern editions of John Foxe’s Acts and Monuments to the execution of the Royal Martyr, Charles I. Specifically, I contend that seventeenth-century plays shaped the secularization of martyrdom in profound ways by staging the sacrificial suffering and deaths of female heroines in a variety of new contexts.