The Portrait of the Sovereign

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Huguenots and Art, C. 1560–1685*

chapter 7 The Huguenots and Art, c. 1560–1685* Andrew Spicer 1 Introduction At an extraordinary meeting of the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture in Paris on 10 October 1681, the president Charles Le Brun read a command from the king’s minister Jean-Baptiste Colbert. On the orders of Louis xiv, those who were members of the Religion Prétendue Reformée were to be deprived of their positions within the Academy; their places were to be taken by Catholics, and membership in the future was to be restricted to this confes- sion. The measure particularly targeted seven men: Henri Testelin (1616–95), Secretary of the Academy; Jean Michelin (1623–96), Assistant Professor; Louis Ferdinand Elle, père (1612–89), Samuel Bernard (1615–87), Jacques Rousseau (1630–93), council members; Mathieu Espagnandel (1616–89) and Louis Ferdinand Elle fils (1648–1717), academicians. The secretary, Testelin, who had painted several portraits of the young king during the 1660s, acquiesced to the royal order but requested that the Academy recognize that he was deprived of his position not due to any personal failings concerning his honesty and good conduct. The academicians acknowledged this to be the case and similarly noted that the other Huguenots present—Bernard, Ferdinand Elle and Michelin—had acquitted their charge with probity and to the satisfaction of the company.1 The following January, the names of Jacob d’Agard and Nicolas Eude were struck from the Academy’s registers because they had both sought refuge in England.2 The expulsion of these artists and sculptors from this learned society was part of the increasing personal and religious restrictions imposed on the Huguenots by Louis xiv, which culminated in the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in October 1685. -

The Petite Commande of 1664: Burlesque in the Gardens of Versailles Thomasf

The Petite Commande of 1664: Burlesque in the Gardens of Versailles ThomasF. Hedin It was Pierre Francastel who christened the most famous the west (Figs. 1, 2, both showing the expanded zone four program of sculpture in the history of Versailles: the Grande years later). We know the northern end of the axis as the Commande of 1674.1 The program consisted of twenty-four Allee d'Eau. The upper half of the zone, which is divided into statues and was planned for the Parterre d'Eau, a square two identical halves, is known to us today as the Parterre du puzzle of basins that lay on the terrace in front of the main Nord (Fig. 2). The axis terminates in a round pool, known in western facade for about ten years. The puzzle itself was the sources as "le rondeau" and sometimes "le grand ron- designed by Andre Le N6tre or Charles Le Brun, or by the deau."2 The wall in back of it takes a series of ninety-degree two artists working together, but the two dozen statues were turns as it travels along, leaving two niches in the middle and designed by Le Brun alone. They break down into six quar- another to either side (Fig. 1). The woods on the pool's tets: the Elements, the Seasons, the Parts of the Day, the Parts of southern side have four right-angled niches of their own, the World, the Temperamentsof Man, and the Poems. The balancing those in the wall. On July 17, 1664, during the Grande Commande of 1674 was not the first program of construction of the wall, Le Notre informed the king by statues in the gardens of Versailles, although it certainly was memo that he was erecting an iron gate, some seventy feet the largest and most elaborate from an iconographic point of long, in the middle of it.3 Along with his text he sent a view. -

OF Versailles

THE CHÂTEAU DE VErSAILLES PrESENTS science & CUrIOSITIES AT THE COUrT OF versailles AN EXHIBITION FrOM 26 OCTOBEr 2010 TO 27 FEBrUArY 2011 3 Science and Curiosities at the Court of Versailles CONTENTS IT HAPPENED AT VErSAILLES... 5 FOrEWOrD BY JEAN-JACqUES AILLAGON 7 FOrEWOrD BY BÉATrIX SAULE 9 PrESS rELEASE 11 PArT I 1 THE EXHIBITION - Floor plan 3 - Th e exhibition route by Béatrix Saule 5 - Th e exhibition’s design 21 - Multimedia in the exhibition 22 PArT II 1 ArOUND THE EXHIBITION - Online: an Internet site, and TV web, a teachers’ blog platform 3 - Publications 4 - Educational activities 10 - Symposium 12 PArT III 1 THE EXHIBITION’S PArTNErS - Sponsors 3 - Th e royal foundations’ institutional heirs 7 - Partners 14 APPENDICES 1 USEFUL INFOrMATION 3 ILLUSTrATIONS AND AUDIOVISUAL rESOUrCES 5 5 Science and Curiosities at the Court of Versailles IT HAPPENED AT VErSAILLES... DISSECTION OF AN Since then he has had a glass globe made that ELEPHANT WITH LOUIS XIV is moved by a big heated wheel warmed by holding IN ATTENDANCE the said globe in his hand... He performed several experiments, all of which were successful, before Th e dissection took place at Versailles in January conducting one in the big gallery here... it was 1681 aft er the death of an elephant from highly successful and very easy to feel... we held the Congo that the king of Portugal had given hands on the parquet fl oor, just having to make Louis XIV as a gift : “Th e Academy was ordered sure our clothes did not touch each other.” to dissect an elephant from the Versailles Mémoires du duc de Luynes Menagerie that had died; Mr. -

Rome Vaut Bien Un Prix. Une Élite Artistique Au Service De L'état : Les

Artl@s Bulletin Volume 8 Article 8 Issue 2 The Challenge of Caliban 2019 Rome vaut bien un prix. Une élite artistique au service de l’État : Les pensionnaires de l’Académie de France à Rome de 1666 à 1968 Annie Verger Artl@s, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/artlas Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, and the Music Commons Recommended Citation Verger, Annie. "Rome vaut bien un prix. Une élite artistique au service de l’État : Les pensionnaires de l’Académie de France à Rome de 1666 à 1968." Artl@s Bulletin 8, no. 2 (2019): Article 8. This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. This is an Open Access journal. This means that it uses a funding model that does not charge readers or their institutions for access. Readers may freely read, download, copy, distribute, print, search, or link to the full texts of articles. This journal is covered under the CC BY-NC-ND license. Artl@s At Work Paris vaut bien un prix. Une élite artistique au service de l’État : Les pensionnaires de l’Académie de France à Rome de 1666 à 1968 Annie Verger* Résumé Le Dictionnaire biographique des pensionnaires de l’Académie de France à Rome a essentiellement pour objet le recensement du groupe des praticiens envoyés en Italie par l’État, depuis Louis XIV en 1666 jusqu’à la suppression du concours du Prix de Rome en 1968. -

Les Peintres Aux Prises Avec Le Décor. Introduction

Les peintres aux prises avec Le d´ecor.Introduction Catherine Cardinal To cite this version: Catherine Cardinal. Les peintres aux prises avec Le d´ecor.Introduction. Catherine Cardinal. Les peintres aux prises avec le d´ecor.Contraintes, innovations, solutions. De la Renaissance `a l'´epoque contemporaine, Presses universitaires Blaise-Pascal, pp.9-12, 2015, 978-2-84516-718-6. <http://pubp.univ-bpclermont.fr/public/Fiche produit.php?titre=Les HAL Id: hal-01225643 https://hal-clermont-univ.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01225643v2 Submitted on 18 Nov 2015 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L'archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destin´eeau d´ep^otet `ala diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publi´esou non, lished or not. The documents may come from ´emanant des ´etablissements d'enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche fran¸caisou ´etrangers,des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou priv´es. S’aventurer dans la réalisation d’un décor intérieur ou extérieur exige des peintres de Sous la direction de s’adapter aux données du lieu et de répondre souvent aux obligations formulées par Catherine Cardinal les commanditaires. De ce faisceau de contraintes surgissent des solutions et parfois des innovations. Dans le présent volume, des historiens de l’art engagent des ques- tionnements sur les difficultés rencontrées par les peintres de l’époque moderne et les artistes contemporains aux prises avec le décor. Après une introduction mettant en lumière l’histoire de l’expression “art décoratif” et celle de la notion d’“arts décoratifs”, le sujet est abordé à travers l’examen de réalisations précises comme le Grand Palais ou le Pont Neuf empaqueté, l’étude de peintres-décorateurs tels Jacques de Lajoüe, l’observation de mises en images suggestives, par exemple la peinture d’architectures, la figuration du temps. -

Bulletin Trimestriel 1Er Trimestre 2016 4.39 Mo

décembre 2015 – 1er trimestre 2016 ÉDITORIAL Le Président, Marc FUMAROLI, de l’Académie française la société des amis du louvre Chers Amis du Louvre, a offert au musée Dans notre dernier Bulletin, je vous avais sous couvert du secret annoncé que notre n La Table de Breteuil, dite Table de Teschen Société se préparait à une acquisition majeure. Vous le savez désormais : il s’agissait (participation) de L’Amour essayant une de ses flèches du sculpteur français Jacques Saly (1717-1776), l’un des artistes préférés de Madame de Pompadour. Notre Conseil d’administration a voté un mécénat exceptionnel de 2.8 millions d’euros en faveur de l’acquisition de ce chef- d’œuvre emblématique du goût rocaille dont la maîtresse royale était l’inspiratrice. Cette somme correspond à plus de la moitié du prix de cette magnifique statue négociée pied à pied à 5.5 millions d’euros avec l’actuel propriétaire. Pour compléter le budget d’acquisition du Louvre, nous avons tenu à nous associer à la campagne d’appel aux dons Tous Mécènes lancée cet automne par le Musée auprès de tous les Français pour réunir 600 000 euros supplémentaires. Cette cam- pagne se poursuivra jusqu’au 14 février 2016. D’ores et déjà, je remercie tous les Amis du Louvre qui ont, à titre personnel, choisi de contribuer à financer, en plus de leur cotisation, cette acquisition patrimoniale. Au-delà de cette campagne d’acquisition, le génie de Madame de Pompadour est également célébré cet hiver au Louvre-Lens qui inaugure le 5 décembre une exposition dont Xavier Salmon, Directeur du département des Arts graphiques est le commis- saire et qui s’intitule: Dansez, embrassez qui vous voudrez. -

Dossier Pédagogique | Charles Le Brun Created with Sketch

DOSSIER PÉDAGOGIQUE 1 Exposition : Crédits photographiques : Commissariat : BÉNÉDICTE GADY, collaboratrice scientifique, département des Arts graphiques, musée du Louvre et h = haut Sommaire NICOLAS MILOVANOVIC, conservateur en chef, b = bas département des Peintures, musée du Louvre. g = gauche d = droite Directeur de la publication : m = milieu LUC PIRALLA, directeur par intérim, musée du Louvre-Lens Texte pédagogique : Charles Le Brun. Le peintre du Roi-Soleil Couverture : © Musée du Louvre / Marc Jeanneteau P. 4 : © RMN-GP (musée du Louvre) / Franck Raux Responsable éditoriale : P. 6 (h) : © RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre) / Michel Urtado THÈME 1 : LE BRUN : PROTÉGÉ DES PUISSANTS 4 JULIETTE GUÉPRATTE, chef du service des Publics, musée du Louvre-Lens P. 6 (b) : © Château de Versailles, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Christophe Fouin P. 7 : © RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre) / Martine Beck-Coppola I. UN JEUNE ARTISTE DISTINGUÉ PAR SÉGUIER ET RICHELIEU 4 Coordination : P. 8 : © De Agostini Picture Library / G. Dagli Orti/Bridgeman Images EVELYNE REBOUL, en charge des actions éducatives, musée du Louvre-Lens P. 9 : © Collection du Mobilier national / Philippe Sébert II. LES PREMIÈRES ARMES AU SERVICE DE FOUQUET 5 P. 10 : © RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre) / Droits réservés III. DE COLBERT À LOUIS XIV 6 Conception : P. 11 : © Musée du Louvre, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Martine Beck-Coppola ISABELLE BRONGNIART, conseillère pédagogique en arts visuels, missionnée au P. 12 : © RMN-GP (musée du Louvre) / Hervé Lewandowski musée du Louvre-Lens P. 13 : © Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence, Italy / Bridgeman Images FLORENCE BOREL, médiatrice au musée du Louvre-Lens P. 15 (h) : © RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre) / Franck Raux THÈME 2 : LE BRUN : ARTISTE D’ENVERGURE 8 PEGGY GARBE, professeur d’arts plastiques au collège Henri Wallon de P. -

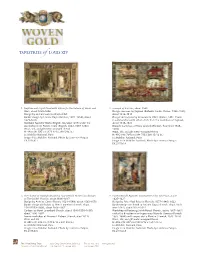

Woven Gold: Tapestries of Louis Xiv

NEWS FROM THE GETTY news.getty.edu | [email protected] DATE: December 1, 2015 MEDIA CONTACT FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Amy Hood Getty Communications (310) 440-6427 [email protected] GETTY MUSEUM PRESENTS WOVEN GOLD: TAPESTRIES OF LOUIS XIV Exhibition is the first major tapestry show in the Western U.S. in four decades Woven Gold amongst a series of exhibitions and special installations at the Getty marking the 300th anniversary of the death of Louis XIV December 15, 2015 – May 1, 2016 at the Getty Center Autumn, before 1669, Gobelins Manufactory (French, 1662 - present). Cartoon attributed to Beaudrin Yvart (French, 1611 - 1690), after Charles Le Brun (French, 1619- 1690). Tapestry, wool, silk and gilt metal-wrapped thread. Le Mobilier National, France. Image © Le Mobilier National. Photo by Lawrence Perquis LOS ANGELES – The art of tapestry weaving in France blossomed during the reign of Louis XIV (r. 1643-1715). Three hundred years after the death of France’s so-called “Sun King,” the J. Paul Getty Museum will showcase 14 monumental tapestries from the French royal collection, revealing the stunning beauty and rich imagery of these monumental works of art. Woven Gold: Tapestries of Louis XIV, exclusively on view at the J. Paul Getty Museum at the Getty Center from December 15, 2015 through May 1, 2016, will be the first major museum exhibition of tapestries in the western United States in four decades. -more- Page 2 “Under Louis XIV, tapestry production flourished in France as never before, with the Crown’s tapestry collection growing to be the greatest in early modern Europe,” says Timothy Potts, director of the J. -

Press Image Sheet

1. Neptune and Cupid Plead with Vulcan for the Release of Venus and 2. Triumph of Bacchus, about 1560 Mars, about 1625–1636 Design overseen by Raphael (Raffaello Sanzio, Italian, 1483–1520), Design by an Unknown Northern Artist about 1518–1519 Border design by Francis Cleyn (German, 1582–1658), about Design and cartoon by Giovanni da Udine (Italian, 1487–1564) 1625–1628 in collaboration with other artists from the workshop of Raphael, Mortlake Tapestry Works (English, founded 1619) under the about 1518–1520 ownership of Sir Francis Crane (English, about 1579–1636) Brussels workshop of Frans Geubels (Flemish, flourished 1545– Wool, silk, and gilt metal-wrapped thread 1585) H: 440 x W: 585 cm (173 1/4 x 230 5/16 in.) Wool, silk, and gilt metal-wrapped thread Le Mobilier National, Paris H: 495 x W: 764 cm (194 7/8 x 300 13/16 in.) Image © Le Mobilier National. Photo by Lawrence Perquis Le Mobilier National, Paris EX.2015.6.3 Image © Le Mobilier National. Photo by Lawrence Perquis EX.2015.6.4 3. The Chariot of Triumph Drawn by Four Piebald Horses (also known 4. Constantius [I] Appoints Constantine as his Successor, about as The Golden Chariot), about 1606–1607 1625–1627 Design by Antoine Caron (French, 1521–1599), about 1563–1570 Design by Peter Paul Rubens (Flemish, 1577–1640), 1622 Border design attributed to Henri Lerambert (French, about Border design attributed to Laurent Guyot (French, about 1575– 1540/1550–1608), about 1606–1607 after 1644), about 1622–1623 Cartoon by Henri Lerambert (French, about 1540/1550–1608), Workshop of Faubourg Saint-Marcel (French, active 1607–1661) about 1606–1607 under the direction of entrepreneurs Marc de Comans (Flemish, Louvre workshop of Maurice I Dubout (French, died 1611) 1563–1644) and François de La Planche (Flemish, 1573–1627) Wool and silk Wool, silk, and gilt metal-wrapped thread H: 483 x W: 614 cm (190 3/16 x 241 3/4 in.) H: 458 x W: 407 cm (180 5/16 x 160 1/4 in.) Le Mobilier National, Paris Le Mobilier National, Paris Image © Le Mobilier National. -

DESSINS TABLEAUX ANCIENS Vendredi 16 Décembre 2011 À 14H

DESSINS TABLEAUX ANCIENS Vendredi 16 décembre 2011 à 14h Hôtel Drouot, salles 1 et 7 9, rue Drouot 75009 Paris Tél. : + 33 (0)1 48 00 20 01 EXPERTS Dessins Cabinet de Bayser 69, rue Sainte-Anne 75002 Paris Tél. : +33 (0)1 47 03 49 87 [email protected] Tableaux anciens Cabinet Éric Turquin 69, rue Sainte-Anne 75002 Paris Tel : +33 (0)1 47 03 48 78 Fax : +33 (0)1 42 60 59 32 www.turquin.fr [email protected] [email protected] Expositions partielles Cabinet de Bayser Jusqu’au mardi 13 décembre 2011 De 14h30 à 18h30 du lundi au vendredi Cabinet Éric Turquin Jusqu’au mardi 13 décembre 2011 De 9h à 19h du lundi au vendredi De 11h à 17h le samedi Exposition publique Hôtel Drouot, salles 1 et 7 Jeudi 15 décembre 2011 de 11h à 18h Vendredi 16 décembre de 11h à 12h Renseignements chez Piasa Émilie Grandin Tel : +33 (0)1 53 34 10 15 [email protected] 1 École italienne du XVIe siècle, entourage de Francesco SALVIATI (1510- 1563) L’Assemblée des dieux Plume et encre brune, lavis brun et rehauts de gouache blanche 27,5 x 19,5 cm (Papier bruni) 1 000 / 1 200 € 2 Atelier de Paolo VÉRONÈSE (1528-1588) Saint Jérôme Crayon noir, rehaut de gouache blanche 29,5 x 17 cm Annoté sur le montage « Étude pour le St Jérôme du Louvre » en bas au centre et « piqué pour un report » en bas à droite (Dessin doublé, piqué en vue d’un report ; pliures et déchirures, taches, épidermures) Notre feuille est à rapprocher du tableau de Paolo Véronèse, Saint Jérôme dans le désert, conservé à l’église de San Pietro Martire à Murano. -

Nicolas Baullery (Vers 1560 - 1630), Enquête Sur Un Peintre Parisien À L’Aube Du Grand Siècle Vladimir Nestorov

Nicolas Baullery (vers 1560 - 1630), enquête sur un peintre parisien à l’aube du Grand Siècle Vladimir Nestorov To cite this version: Vladimir Nestorov. Nicolas Baullery (vers 1560 - 1630), enquête sur un peintre parisien à l’aube du Grand Siècle . Art et histoire de l’art. 2014. dumas-01543952 HAL Id: dumas-01543952 https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-01543952 Submitted on 21 Jun 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License ÉCOLE DU LOUVRE Vladimir NESTOROV Nicolas Baullery (v.1560 – 1630) Enquête sur un peintre parisien à l’aube du Grand Siècle Mémoire de recherche (2de année de 2e cycle) en histoire de l'art appliquée aux collections présenté sous la direction de M. Olivier BONFAIT août 2014 Le contenu de ce mémoire est publié sous la licence Creative Commons CC BY NC ND 1 NICOLAS BAULLERY (VERS 1560 – 1630). ENQUETE SUR UN PEINTRE PARISIEN A L’AUBE DU GRAND SIECLE 2 Table des matières Avant-Propos .............................................................................................................................. 3 Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 5 I : Etre peintre à Paris vers 1600................................................................................................. 9 A : La peinture parisienne sous Henri IV : un creuset artistique fécond. -

The Project Gutenberg Ebook of Pictures Every Child Should Know, by Dolores Bacon

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Pictures Every Child Should Know, by Dolores Bacon Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this or any other Project Gutenberg eBook. This header should be the first thing seen when viewing this Project Gutenberg file. Please do not remove it. Do not change or edit the header without written permission. Please read the "legal small print," and other information about the eBook and Project Gutenberg at the bottom of this file. Included is important information about your specific rights and restrictions in how the file may be used. You can also find out about how to make a donation to Project Gutenberg, and how to get involved. **Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts** **eBooks Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971** *****These eBooks Were Prepared By Thousands of Volunteers!***** Title: Pictures Every Child Should Know Author: Dolores Bacon Release Date: November, 2004 [EBook #6932] [This file was first posted on February 12, 2003] Edition: 10 Language: English Character set encoding: iso-8859-1 *** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK, PICTURES EVERY CHILD SHOULD KNOW *** Arno Peters, Branko Collin, Tiffany Vergon, Charles Aldarondo, Charles Franks, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team PICTURES EVERY CHILD SHOULD KNOW A SELECTION OF THE WORLD'S ART MASTERPIECES FOR YOUNG PEOPLE BY DOLORES BACON Illustrated from Great Paintings ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Besides making acknowledgments to the many authoritative writers upon artists and pictures, here quoted, thanks are due to such excellent compilers of books on art subjects as Sadakichi Hartmann, Muther, C.