THE ALLIED EXPEDITIONARY FORCES PROGRAMME Gen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BBC SOUND BROADCASTING Its Engineering Development

Published by the British Broadcorrmn~Corporarion. 35 Marylebone High Sneer, London, W.1, and printed in England by Warerlow & Sons Limited, Dunsruble and London (No. 4894). BBC SOUND BROADCASTING Its Engineering Development PUBLISHED TO MARK THE 4oTH ANNIVERSARY OF THE BBC AUGUST 1962 THE BRITISH BROADCASTING CORPORATION SOUND RECORDING The Introduction of Magnetic Tape Recordiq Mobile Recording Eqcupment Fine-groove Discs Recording Statistics Reclaiming Used Magnetic Tape LOCAL BROADCASTING. STEREOPHONIC BROADCASTING EXTERNAL BROADCASTING TRANSMITTING STATIONS Early Experimental Transmissions The BBC Empire Service Aerial Development Expansion of the Daventry Station New Transmitters War-time Expansion World-wide Audiences The Need for External Broadcasting after the War Shortage of Short-wave Channels Post-war Aerial Improvements The Development of Short-wave Relay Stations Jamming Wavelmrh Plans and Frwencv Allocations ~ediumrwaveRelav ~tatik- Improvements in ~;ansmittingEquipment Propagation Conditions PROGRAMME AND STUDIO DEVELOPMENTS Pre-war Development War-time Expansion Programme Distribution Post-war Concentration Bush House Sw'tching and Control Room C0ntimn.t~Working Bush House Studios Recording and Reproducing Facilities Stag Economy Sound Transcription Service THE MONITORING SERVICE INTERNATIONAL CO-OPERATION CO-OPERATION IN THE BRITISH COMMONWEALTH ENGINEERING RECRUITMENT AND TRAINING ELECTRICAL INTERFERENCE WAVEBANDS AND FREQUENCIES FOR SOUND BROADCASTING MAPS TRANSMITTING STATIONS AND STUDIOS: STATISTICS VHF SOUND RELAY STATIONS TRANSMITTING STATIONS : LISTS IMPORTANT DATES BBC ENGINEERING DIVISION MONOGRAPHS inside back cover THE BEGINNING OF BROADCASTING IN THE UNITED KINGDOM (UP TO 1939) Although nightly experimental transmissions from Chelmsford were carried out by W. T. Ditcham, of Marconi's Wireless Telegraph Company, as early as 1919, perhaps 15 June 1920 may be looked upon as the real beginning of British broadcasting. -

MCPS TV Fpvs

MCPS Broadcast Blanket Distribution - TV FPV Rates paid July 2014 Non Peak Non Peak Progs Progs P(ence) P(ence) Peak FPV Non Peak (covered (covered Manufact Period Rate (per Rate (per (per FPV (per by by Source/S urer Source Link (YYMMYYM weighted weighted weighted weighted blanket blanket Licensee Channel Name hort Code udc Number Type code M) second) second) minute) minute) licence) licence) AATW Ltd Channel AKA CHNAKA S1759 287294 208 qbc 13091312 0.015 0.009 Y Y BBC BBC 1 BBCTVD Z0003 5258 201 qdw 14011403 75.452 37.726 45.2712 22.6356 Y Y BBC BBC 2 BBC2 Z0004 316168 201 qdx 14011403 17.879 8.939 10.7274 5.3634 Y Y BBC BBC ALBA BBCALB Z0008 232662 201 qe2 14011403 6.48 3.24 3.888 1.944 Y Y BBC BBC HD BBCHD Z0010 232654 201 qe4 14011403 6.095 3.047 3.657 1.8282 Y Y BBC BBC Interactive BBCINT AN120 251209 201 qbk 14011403 6.854 4.1124 Y Y BBC BBC News BBC NE Z0007 127284 201 qe1 14011403 8.193 4.096 4.9158 2.4576 Y Y BBC BBC Parliament BBCPAR Z0009 316176 201 qe3 14011403 13.414 6.707 8.0484 4.0242 Y Y BBC BBC Side Agreement for S4C BBCS4C Z0222 316184 201 qip 14011403 7.747 4.6482 Y Y BBC BBC3 BBC3 Z0001 126187 201 qdu 14011403 15.677 7.838 9.4062 4.7028 Y Y BBC BBC4 BBC4 Z0002 158776 201 qdv 14011403 9.205 4.602 5.523 2.7612 Y Y BBC CBBC CBBC Z0005 165235 201 qdy 14011403 8.96 4.48 5.376 2.688 Y Y BBC Cbeebies CBEEBI Z0006 285496 201 qdz 14011403 12.457 6.228 7.4742 3.7368 Y Y BBC Worldwide BBC Entertainment Africa BBCENA Z0296 286601 201 qk2 14011403 5.556 2.778 3.3336 1.6668 N Y BBC Worldwide BBC Entertainment Nordic BBCENN Z0300 -

Bpsr N Nte Cei B Nary

5689 FRMS cover:52183 FRMS cover 142 18/02/2013 15:00 Page 1 Spring 2013 No. 158 £2.00 Bulletin RPS bicentenary 5689 FRMS cover:52183 FRMS cover 142 18/02/2013 15:00 Page 2 5689 FRMS pages:Layout 1 20/02/2013 17:11 Page 3 FRMS BULLETIN Spring 2013 No. 158 CONTENTS News and Comment Features Editorial 3 Cover story: RPS Bicentenary 14 Situation becoming vacant 4 A tale of two RPS Gold Medal recipients 21 Vice-President appointment 4 FRMS Presenters Panel 22 AGM report 5 Changing habits 25 A view from Yorkshire – Jim Bostwick 13 International Sibelius Festival 27 Chairman’s column 25 Anniversaries for 2014 28 Neil Heayes remembered 26 Roger’s notes, jottings and ramblings 29 Regional Groups Officers and Committee 30 Central Region Music Day 9 YRG Autumn Day 10 Index of Advertisers Societies Hyperion Records 2 News from Sheffield, Bath, Torbay, Horsham, 16 Arts in Residence 12 Street and Glastonbury, and West Wickham Amelia Marriette 26 Nimbus Records 31 CD Reviews Presto Classical Back cover Hyperion Dohnányi Solo Piano Music 20 Harmonia Mundi Britten and Finzi 20 Dutton Epoch British Music for Viola and orch. 20 For more information about the FRMS please go to www.thefrms.co.uk The editor acknowledges the assistance of Sue Parker (Barnsley Forthcoming Events and Huddersfield RMSs) in the production of this magazine. Scarborough Music Weekend, March 22nd - 25th (page 13) Scottish Group Spring Music Day, April 27th (page 13) th th Daventry Music Weekend, April 26 - 28 (pages 4 & 8) Front cover: 1870 Philharmonic Society poster, courtesy of th West Region Music Day, Bournemouth, June 4 RPS Archive/British Library th FRMS AGM, Hinckley, November 9 EDITORIAL Paul Astell NOTHER AGM HAS PASSED, as has another discussion about falling membership and A the inability to attract new members. -

“Talkin' 'Bout My Generation”: Radio Caroline and Cultural Hegemony

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sussex Research Online Financial control, blame avoidance and Radio Caroline: Talkin’ ‘bout my generation Article (Accepted Version) Miley, Frances M and Read, Andrew F (2017) Financial control, blame avoidance and Radio Caroline: Talkin’ ‘bout my generation. Accounting History, 22 (3). pp. 301-319. ISSN 1032-3732 This version is available from Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/67723/ This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies and may differ from the published version or from the version of record. If you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the URL above for details on accessing the published version. Copyright and reuse: Sussex Research Online is a digital repository of the research output of the University. Copyright and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable, the material made available in SRO has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. -

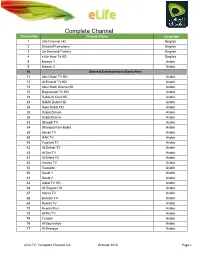

Complete Channel List October 2015 Page 1

Complete Channel Channel No. List Channel Name Language 1 Info Channel HD English 2 Etisalat Promotions English 3 On Demand Trailers English 4 eLife How-To HD English 8 Mosaic 1 Arabic 9 Mosaic 2 Arabic 10 General Entertainment Starts Here 11 Abu Dhabi TV HD Arabic 12 Al Emarat TV HD Arabic 13 Abu Dhabi Drama HD Arabic 15 Baynounah TV HD Arabic 22 Dubai Al Oula HD Arabic 23 SAMA Dubai HD Arabic 24 Noor Dubai HD Arabic 25 Dubai Zaman Arabic 26 Dubai Drama Arabic 33 Sharjah TV Arabic 34 Sharqiya from Kalba Arabic 38 Ajman TV Arabic 39 RAK TV Arabic 40 Fujairah TV Arabic 42 Al Dafrah TV Arabic 43 Al Dar TV Arabic 51 Al Waha TV Arabic 52 Hawas TV Arabic 53 Tawazon Arabic 60 Saudi 1 Arabic 61 Saudi 2 Arabic 63 Qatar TV HD Arabic 64 Al Rayyan HD Arabic 67 Oman TV Arabic 68 Bahrain TV Arabic 69 Kuwait TV Arabic 70 Kuwait Plus Arabic 73 Al Rai TV Arabic 74 Funoon Arabic 76 Al Soumariya Arabic 77 Al Sharqiya Arabic eLife TV : Complete Channel List October 2015 Page 1 Complete Channel 79 LBC Sat List Arabic 80 OTV Arabic 81 LDC Arabic 82 Future TV Arabic 83 Tele Liban Arabic 84 MTV Lebanon Arabic 85 NBN Arabic 86 Al Jadeed Arabic 89 Jordan TV Arabic 91 Palestine Arabic 92 Syria TV Arabic 94 Al Masriya Arabic 95 Al Kahera Wal Nass Arabic 96 Al Kahera Wal Nass +2 Arabic 97 ON TV Arabic 98 ON TV Live Arabic 101 CBC Arabic 102 CBC Extra Arabic 103 CBC Drama Arabic 104 Al Hayat Arabic 105 Al Hayat 2 Arabic 106 Al Hayat Musalsalat Arabic 108 Al Nahar TV Arabic 109 Al Nahar TV +2 Arabic 110 Al Nahar Drama Arabic 112 Sada Al Balad Arabic 113 Sada Al Balad -

23 February 2018 Page 1 of 8 SATURDAY 17 FEBRUARY 2018 Episode Five Agatha Christie Novel in a Poll in September 2015

Radio 4 Extra Listings for 17 – 23 February 2018 Page 1 of 8 SATURDAY 17 FEBRUARY 2018 Episode Five Agatha Christie novel in a poll in September 2015. Mary Ann has an unwelcome encounter with a presence from Directed by Mary Peate. SAT 00:00 BD Chapman - Orbiter X (b0784dyd) her past. Shawna is upset by Michael's revelation. First broadcast on BBC Radio 4 in 2010. Inside the Moon StationDr Max Kramer has tricked the crew of Dramatised by Lin Coghlan SAT 07:30 Byzantium Unearthed (b00dxdcs) Orbiter 2, but what exactly is Unity up to on the Moon? Producer Susan Roberts Episode 1Historian Bettany Hughes begins a series that uses the BD Chapman's adventure in the conquest of space in 14 parts. Director Charlotte Riches latest archaeological evidence to learn more about the empire of Stars John Carson as Captain Bob Britton, Andrew Crawford as For more than three decades, Armistead Maupin's Tales of the Byzantium and the people who ruled it. Captain Douglas McClelland, Barrie Gosney as Flight Engineer City series has blazed a trail through popular culture-from Bettany learns how treasures found in the empire's capital, Hicks, Donald Bisset as Colonel Kent, Gerik Schelderup as Max ground-breaking newspaper serial to classic novel. Radio 4 are modern-day Istanbul, reveal much about the life and importance Kramer, and Leslie Perrins as Sir Charles Day. With Ian Sadler dramatising the full series of the Tales novels for the very first of a civilisation that, whilst being devoutly Christian and the and John Cazabon. -

MGEITF Prog Cover V2

Contents Welcome 02 Sponsors 04 Festival Information 09 Festival Extras 10 Free Clinics 11 Social Events 12 Channel of the Year Awards 13 Orientation Guide 14 Festival Venues 15 Friday Sessions 16 Schedule at a Glance 24 Saturday Sessions 26 Sunday Sessions 36 Fast Track and The Network 42 Executive Committee 44 Advisory Committee 45 Festival Team 46 Welcome to Edinburgh 2009 Tim Hincks is Executive Chair of the MediaGuardian Elaine Bedell is Advisory Chair of the 2009 Our opening session will be a celebration – Edinburgh International Television Festival and MediaGuardian Edinburgh International Television or perhaps, more simply, a hoot. Ant & Dec will Chief Executive of Endemol UK. He heads the Festival and Director of Entertainment and host a special edition of TV’s Got Talent, as those Festival’s Executive Committee that meets five Comedy at ITV. She, along with the Advisory who work mostly behind the scenes in television times a year and is responsible for appointing the Committee, is directly responsible for this year’s demonstrate whether they actually have got Advisory Chair of each Festival and for overall line-up of more than 50 sessions. any talent. governance of the event. When I was asked to take on the Advisory Chair One of the most contentious debates is likely Three ingredients make up a great Edinburgh role last year, the world looked a different place – to follow on Friday, about pay in television. Senior TV Festival: a stellar MacTaggart Lecture, high the sun was shining, the banks were intact, and no executives will defend their pay packages and ‘James Murdoch’s profile and influential speakers, and thought- one had really heard of Robert Peston. -

An Economic Review of the Extent to Which the BBC Crowds out Private Sector Activity

An economic review of the extent to which the BBC crowds out private sector activity A KPMG Report commissioned by the BBC Trust October 2015 FINAL REPORT Important Notice This report (‘Report’) has been prepared by KPMG LLP in accordance with specific terms of reference (‘terms of reference’) agreed between the British Broadcasting Corporation Trust (‘BBC Trust’ or ‘the Addressee’), and KPMG LLP (‘KPMG’). KPMG has agreed that the Report may be disclosed to third parties. KPMG wishes all parties to be aware that KPMG’s work for the Addressee was performed to meet specific terms of reference agreed between the Addressee and KPMG LLP and that there were particular features determined for the purposes of the engagement. The Report should not therefore be regarded as suitable to be used or relied on by any other person or for any other purpose. The Report is issued to all parties on the basis that it is for information only. Should any party choose to rely on the Report they do so at their own risk. KPMG will accordingly accept no responsibility or liability in respect of the Report to any party other than the Addressee. KPMG does not provide any assurance on the appropriateness or accuracy of sources of information relied upon and KPMG does not accept any responsibility for the underlying data used in this report. No review of this report for factual accuracy has been undertaken. For this report, the BBC Trust has not engaged KPMG to perform an assurance engagement conducted in accordance with any generally accepted assurance standards and consequently no assurance opinion is expressed. -

Nashville Community Theatre: from the Little Theatre Guild

NASHVILLE COMMUNITY THEATRE: FROM THE LITTLE THEATRE GUILD TO THE NASHVILLE COMMUNITY PLAYHOUSE A THESIS IN Theatre History Presented to the Faculty of the University of Missouri – Kansas City in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS by ANDREA ANDERSON B.A., Trevecca Nazarene University, 2003 Kansas City, Missouri 2012 © 2012 ANDREA JANE ANDERSON ALL RIGHTS RESERVED THE LITTLE THEATRE MOVEMENT IN NASHVILLE, TENNESSEE: THE LITTLE THEATRE GUILD AND THE NASHVILLE COMMUNITY PLAYHOUSE Andrea Jane Anderson, Candidate for the Master of Arts Degree University of Missouri - Kansas City, 2012 ABSTRACT In the early 20th century the Little Theatre Movement swept through the United States. Theatre enthusiasts in cities and towns across the country sought to raise the standards of theatrical productions by creating quality volunteer-driven theatre companies that not only entertained, but also became an integral part of the local community. This paper focuses on two such groups in the city of Nashville, Tennessee: the Little Theatre Guild of Nashville (later the Nashville Little Theatre) and the Nashville Community Playhouse. Both groups shared ties to the national movement and showed a dedication for producing the most current and relevant plays of the day. In this paper the formation, activities, and closure of both groups are discussed as well as their impact on the current generation of theatre artists. iii APPROVAL PAGE The faculty listed below, appointed by the Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences, have examined a thesis titled “Nashville Community Theatre: From the Little Theatre Guild to the Nashville Community Playhouse,” presented by Andrea Jane Anderson, candidate for the Master of Arts degree, and certify that in their opinion it is worthy of acceptance. -

Zenderlijst Digitaal

Extra Alles in 1 Extra Zender Kanaal Zender Kanaal Nick Jr. 27 BBC Entertainment 46 Cartoon Network 28 AMC 69 Boomerang 29 NGC Wild 73 BabyTV# 31 Discovery World 75 Pebble TV 32 Discovery Science 76 CBBC 43 RTL Lounge 78 BBC 4 / Cbeebies 44 RTL Crime 79 BBC Entertainment 46 Horse & Country TV 80 RTL 2 +HbbTV 58 Mezzo 89 Kabel 1 +HbbTV 59 Eurosport 2 +HD 92 Vox +HbbTV 62 SLAM! TV 135 AMC 69 VH-1 Classic 138 Animal Planet 72 BBC 1 HD 241 NGC Wild 73 BBC 2 HD 242 Discovery World 75 CBBC HD 243 Discovery Science 76 BBC 4 / Cbeebies HD 244 RTL Lounge 78 Animal Planet HD 272 RTL Crime 79 Travel Channel HD 281 Horse & Country TV 80 iConcerts HD 292 Travel Channel 81 Stingray dJazz HD 293 Fashion TV# 82 NPO 101 502 Mezzo 89 NPO Cultura 503 Stingray Brava 90 NPO Zapp Xtra 517 Eurosport 2 +HD 92 FOX Sports Eredivisie 1 +HD 541 Motors TV HD 93 FOX Sports Eredivisie 3 +HD 543 MTV Brandnew 133 FOX Sports Eredivisie 5 +HD 545 SLAM! TV 135 VH-1 Classic 138 TV 538 139 Playboy TV* 161 Adult Channel* 162 Brazzers TV* 163 NPO 101 502 NPO Cultura 503 NPO Zapp Xtra 517 Instellen van de ontvanger De door u aangeschafte digitale ontvanger of televisie moet worden ingesteld om de digitale zenders van Kabelnet Veendam te kunnen * Deze zenders kunnen op verzoek geblokkeerd worden ontvangen. # Kan alleen met een HD-ontvanger bekeken worden In het menu van de digitale ontvanger of televisie voert u de volgende codes in: Frequentie : 234.000 Net ID : 9641 Qamformaat : Qam 64 Symboolrate (K-Baud) : 6875 Basispakket TV Internationaal Film Zender Kanaal Zender Kanaal -

Delivering Quality First – Page 2

The newspaper for BBC pensioners – with highlights from Ariel A future plan Delivering Quality First – Page 2 Photo courtesy of Jeff Overs November 2011 • Issue 8 tales of Print edition of Musical televison ariel to close memories Centre Page 2 Page 6 Page 9 NEWS • MEMoriES • ClaSSifiEdS • Your lEttErS • obituariES • CroSPEro 02 uPdatE froM thE bbC commissioning and scheduling will be • More landmark output for Radio 4 (which closely aligned. sees its overall budget hardly changed). Delivering Quality First • Job grading, redundancy terms and • More money for the Proms. unpredictability allowances will be • The further rollout of HD and DAB. Mark Thompson sets out ‘a plan for living within our means’ as ‘modernised’ and reformed. A consultation he reveals job losses, output changes, relocations, structured process on those proposals begins Union response immediately. The National Union of Journalists issued a re-investment in a digital public space, and new content and • Production will be streamlined into a swift response to the announcement, calling programmes on BBC services. single UK production economy. for the licence fee negotiations to be re- • Radio and TV commissioning for Science opened and ‘a proper public debate about Fewer staff, a flatter structure, more jobs • All new daytime programming will be and Music will be brought together. BBC funding’. shifting to Salford and more output from on BBC One. In a statement the NUJ said: ‘The BBC will outside London, these are the conclusions of • BBC Two’s daytime output will focus on Reinvestment not be the same organisation if these cuts go the Delivering Quality First process. -

AF Grelhacanais

Abr.19 Grelha de canais Fibra Grelha de canais Fibra A grelha de canais da NOS está organizada por temática, para que tenha uma experiência de zapping intuitiva e aceda de forma imediata aos canais da sua preferência. A NOS agrupou ainda os canais em Alta Definição (HD) no final de cada temática para que os encontre facilmente, com exceção das primeiras 20 posições da grelha, onde pode encontrar a melhor qualidade disponível de cada canal. Lembramos que os canais estão disponíveis mediante o pacote subscrito. Generalistas Entretenimento 1 RTP 1 HD 56 E! Entertainment 2 RTP 2 57 FTV 3 SIC HD 58 BBC Entertainment 4 TVI 70 Canal Q 5 SIC Notícias HD 71 TLC 6 RTP 3 72 MTV Portugal 7 TVI 24 82 E! Entertainment HD 8 CMTV HD 83 FTV HD 10 Globo HD 96 24 Kitchen HD 11 SIC Mulher HD 97 Food Network HD 12 TVI Reality 98 MTV Portugal HD 13 Porto Canal HD 99 Fine Living Network HD 14 SIC Caras HD 170 Globo NOW HD 15 SIC Radical HD 180 Canal 180 16 RTP Memória 250 DogTV 36 Porto Canal HD 441 Hispasat 4K 301 RTP 1 442 Canal NOS 4K 303 SIC 700 Canal NOS 305 SIC Notícias 308 CMTV 310 Globo Documentários 311 SIC Mulher 100 Discovery Channel 313 Porto Canal 105 National Geographic 314 SIC Caras 107 National Geographic WILD 315 SIC Radical 109 Odisseia 110 Travel Channel 112 Canal de História Desporto Nacional 113 Crime + Investigation 9 Sport TV + HD 114 Blaze 19 Sport TV 1 115 Discovery Showcase HD 20 Sport TV 2 116 National Geographic HD 21 Sport TV 3 117 National Geographic WILD HD 22 Sport TV 4 118 Odisseia HD 23 Sport TV 5 119 Travel Channel HD 24 Sport