£N4 Tk) the Degree

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

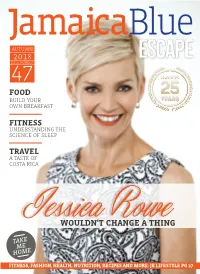

Escape Issue47 Number Food Build Your Own Breakfast

JamaicaBlue AUTUMN 2018 ESCAPE ISSUE47 NUMBER FOOD BUILD YOUR OWN BREAKFAST FITNESS UNDERSTANDING THE SCIENCE OF SLEEP TRAVEL A TASTE OF COSTA RICA JessicaRoweWOULDN'T CHANGE A THING TAKE ME HOME FITNESS, FASHION, HEALTH, NUTRITION, RECIPES AND MORE: JB LIFESTYLE PG 27 JB47-p01 Cover.indd 2 18/01/2018 23:50:49 JamaicaBlue 2018 AutumnIssue 47 FEATURES 12 COVER FEATURE p04 Jessica Rowe 14 FOOD Build your own breakfast 17 SPORT The Commonwealth Games 20 TRAVEL JAMAICA BLUE PTY LTD Beautiful Costa Rica ACN 059 236 387 22 FOOD Unit 215F1, Building 215 p14 The Entertainment Quarter A taste of chocolate p06 122 Lang Road 24 BEACON FOUNDATION Moore Park NSW 2021 PO Box 303 A pathway to success Double Bay NSW 1360 26 THE BARISTA SAYS... T 1800 622 338 Meet Jaydan Hancock of (Australia only) T 02 9302 2200 Jamaica Blue Harbour Town F 02 9302 2212 E [email protected] LIFESTYLE SECTION New Zealand Office 28 FINANCE T +64 9377 1901 Making the most of Amazon F +64 9377 1908 30 CAREER E [email protected] Pressing pause JAMAICA BLUE ESCAPE™ 32 HEALTH Editor The science of sleep Rachel Stuart 34 FITNESS Art Director The top 5 free apps Natalie Delarey p17 36 FASHION Nutrition Specialist Six great new autumn looks Sharon Natoli 40 BOOKS Welcome to the autumn Fashion Editor Autumn reads edition of Jamaica Blue Cheryl Tan 42 NUTRITION Escape. In this issue we chat Eating for good mental health to Australian TV veteran, Contributors Jessica Rowe, try our new John Burfitt 44 NUTRITION WITH Shane Conroy SHARON NATOLI 'build your own' breakfast Sarah Megginson You are when you eat menu, ready ourselves for the Gold Coast Thomas Mitchell 46 RECIPES Commonwealth Games, try on the Autumn never tasted so good latest fashions and more. -

BUSINESS Brittain Stone EDC Won’T Release Pier Study Long on Talent by Lisa J

SATURDAY • MAY 22, 2004 Including Carroll Gardens-Cobble Hill Paper, Downtown News, DUMBO Paper and Fort Greene-Clinton Hill Paper Brooklyn’s REAL newspapers Published every Saturday by Brooklyn Paper Publications Inc, 55 Washington Street, Suite 624, Brooklyn NY 11201. Phone 718-834-9350 • www.BrooklynPapers.com • © 2004 Brooklyn Paper Publications • 20 pages including GO BROOKLYN • Vol. 27, No. 20 BWN • Saturday, May 22, 2004 • FREE CITY TO PUBLIC ON B’KLYN WATERFRONT: NONE OF YOUR THIS WEEKEND BUSINESS Brittain Stone EDC won’t release pier study Long on talent By Lisa J. Curtis and Urban Divers. Michael Sherman, an EDC spokesman, told GO Brooklyn editor An exhibit of a wide variety of artworks by EXCLUSIVE The Brooklyn Papers, “There are no such plans hundreds of artists, the Brooklyn Waterfront at the moment,” when asked about the study’s re- NOT JUST NETS Critically acclaimed talents and youth Artists Coalition Pier Show 12 continues, and lease. THE NEW BROOKLYN groups alike will strut their stuff on the will be on display in the warehouse at 499 Van By Deborah Kolben “It was always just going to be for our internal Beard Street Pier in Red Hook this Sat- Brunt St. from noon to 6 pm. The Brooklyn Papers urday, May 22, as part of the 10th annual The Arts Festival events take place from 1 pm use,” he said, adding that an executive summary Hamilton, Rabinovitz & Alschuler, saying they Red Hook residents and merchants who or “highlights” of the study might be released “at Red Hook Waterfront Arts Festival. to 5 pm at the Beard Street Pier, Van Brunt ignored community input throughout the process Among the troupes that will take the stage are Street at the Red Hook Channel, and the per- have been eagerly awaiting the results of a some point.” and came in with a preconceived agenda to major city-sponsored study on the future of “Our thinking is that we’re just using the in- the Urban Bush Women, Dance Wave Kids Com- formances are free. -

Replacing the Merchant Navy 16 MANAGING AGENTS for IIOBSONS BAY DOCK and Christmas Convoy 25 Irngineering CO

CONTENTS Vol. 19. JANUARY. I956. SEA TRAVEL EDITORIAL: M.V. "DUNTROON"— 10.500 Ion. A Healthy Criticism 4 Protection In The Atomic Age 5 MELBOURNE AT ITS BEST! STEAMSHIP A 7TICLES: CO. LTD. Head Office: A New Submarine Hunter 6 31 KING ST., MELBOURNE Left Look At Russia's Neval Strength 8 BRANCHES OR AGENCIES AT ALL PORTS TO ENGLAND VIA SUEZ Hobart Race 16 MANAGING AGENTS FOR By FIRST & TOURIST CLASS AND ONE CLASS VESSELS HOBSONS BAY DOCK AND "Control Of Atlantic Vital" — Montgomery 26 ENGINEERING CO. PTY. LTD. Agentt: Works: Williamstown. Victoria MACDONALD, HAMILTON & CO. Rebuilding The French Navy 30 HODGE ENGINEERING CO. PTY. LTD. SVDNEy BRISBANE. MELBOURNE PERTH NEWCASTLE FEATURES: Works: Sussex St., Sydney, ELDER. SMITH & CO. LIMITED and ADELAIDE Newt Of The World's Navies 14 COCKBURN ENGINEERING PENINSULAR I O R I E N I A I c o PTY. LTD. fine, in fcngiond witn hmiUC liability! Maritime News Of The World 20 Works: Mines Rd., Frenande. SHIP RFPAIRFRS. FTC Personalities 23 Book Reviews 27 For Sea Cadets 27 THE UNITED SHIP SERVICES »ub ished by The Navy League of Australia. 83 Pitt Street. Sydney N.S.W. PTY. LTD. Telephone BU 1771. Official Organ of the Navy League of Australia: the Merchant Service Guild of Australasia: the El-Naval Men's Association (Federal|. UOSCRIPTION RATE: 12 Issues post free in the British Empire. 20/-. -opies of "Hera'd" photograohs used may be obtained dirert from Pho'a Sa'es. Sydney Morning Hera'd. Hunter Street. Sydney. When ships of the Navy " heave to" this rope holds fast! ALL CLASSES OF SHIP REPAIRS AND FITTINGS UNDERTAKEN «K. -

The Ownership of Copyrightable Contributions in the Wake of Garcia V

The Ownership of Copyrightable Contributions in the Wake of Garcia v. Google and 16 Casa Duse v. Merkin The Second and Ninth Circuits have both recently held that an actor or a director may not, in the normal course, own a copyright to their individual contributions to an integrated work of authorship like a film. This panel will explore whether these decisions were correct, and the real-world impact they will have on the motion picture industry, and on contributions to integrated works. Moderator: Justin Hughes Hon. William Byrne Professor of Law, Loyola Law School Panelists: Eleanor Lackman Partner, Cowan, DeBaets, Abrahams & Sheppard LLP F. Jay Dougherty Professor of Law, Director of Entertainment & Media Law Institute and Concentration Program, Loyola Law School Christopher Newman Associate Professor of Law, George Mason University School of Law Danielle Van Lier Senior Counsel, Intellectual Property and Contracts, SAG-AFTRA TABLE OF CONTENTS Garcia v. Google, Inc., 786 F.3d 733 (9th Cir. 2015)………………………………………...…..1 16 Casa Duse, LLC v. Merkin, 791 F.3d 247 (2d Cir. 2015)…………………………………….22 F. Jay Dougherty, Not a Spike Lee Joint? Issues in the Authorship of Motion Pictures Under U.S. Copyright Law, 49 UCLA L. Rev. 225 (2001)…………………………………......41 GARCIA v. GOOGLE, INC. 733 Cite as 786 F.3d 733 (9th Cir. 2015) changing the content and context of ongo- ing global discourse. The constitutional Cindy Lee GARCIA, Plaintiff– violation is not cured by restoring access Appellant, to the video well over a year later, long v. after the time when it was most relevant to GOOGLE, INC., a Delaware Corpora- the debate and of greatest interest to the tion; YouTube, LLC, a California lim- public. -

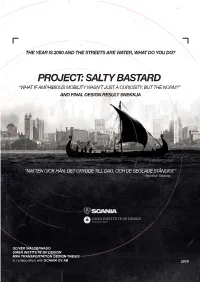

Salty Bastard “What If Amphibious Mobility Wasn’T Just a Curiosity, but the Norm?” and Final Design Result Snekkja

THE YEAR IS 2050 AND THE STREETS ARE WATER, WHAT DO YOU DO? PROJECT: SALTY BASTARD “WHAT IF AMPHIBIOUS MOBILITY WASN’T JUST A CURIOSITY, BUT THE NORM?” AND FINAL DESIGN RESULT SNEKKJA “NATTEN GICK HÄN, DET GRYDDE TILL DAG, OCH DE SEGLADE STÄNDIGT.” - (Homeros’ Odyssée) OLIVER WALDERHAUG UMEÅ INSTITUTE OF DESIGN MFA TRANSPORTATION DESIGN THESIS in collaboration with SCANIA CV AB 2019 <PROJECT: SALTY BASTARD> UMEÅ ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A SINCERE THANK YOU TO EVERYONE INVOLVED IN THIS JOURNEY First and foremost, I’d like to thank the Scania team for the support, not only throughout this project but also my internship. Kristofer for giving me the opportunity to come aboard, Ingrid for mentoring and supporting me along the way and Christian for his never wavering positivity and energy. Thank you Umeå Institute of Design, with all it’s fantastic teachers and staff for these strangely long and short years, all the way from my BFA years to now went by in a flash, yet I feel fifteen years older than when I started. It’s been a privilege to study with such a range of professional and caring people in the organisation - always putting us students in focus and doing the utmost you could to put us in our best light and on a path to success. I’ll always be grateful for that. To my classmates, you are the greatest group of people I could have imagined studying with, and I’m sure you will all go on to do great things. The sense of camaraderie we have is hard to put into words, and I have nothing but the utmost respect and love for each and every one of you. -

A Review on Design and Analysis of Amphibious Vehicle

International Journal of Science, Technology & Management www.ijstm.com Volume No.04, Issue No. 01, January 2015 ISSN (online): 2394-1537 A REVIEW ON DESIGN AND ANALYSIS OF AMPHIBIOUS VEHICLE Prof. P. S. Shirsath1, Prof. M. S. Hajare2, Prof. G. D. Sonawane3, Mr. Atul Kuwar4, Mr. S. U. Gunjal5 1,2,3Asst. Prof., Department of Mechanical Engineering, Sandip Foundation’s- SITRC, Mahiraavani, Trimbak Road, Nashik, Maharashtra, Savitribai Phule Pune University, Pune, Maharashtra, (India) 4Department of Mechanical Engineering, Sandip Foundation’s- SITRC, Mahiraavani, Trimbak Road, Nashik, Maharashtra, Savitribai Phule Pune University, Pune, Maharashtra, (India) 5P. G. Student, Department of Mechanical Engineering, GS Mandal’s- MIT, Aurangabad, Maharashtra, Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Marathwada University, Aurangabad, Maharashtra, (India) ABSTRACT An Amphibious vehicle is a means of transport, viable on land as well as on water even under water. It is simply may also called as Amphibian. Amphibious vehicle is a concept of vehicle having versatile usage. It can be put forward for the commercialization purpose with respect to various applications like in the field of military and rescue operations. Researchers are working on amphibious vehicle with capability to run in adverse conditions in efficient way. This paper focuses on concept of amphibious vehicle in detail. In later stage of paper we have explain and described the design and analysis of amphibious car. We have followed proper design procedure and enlisted the material used in detail. Capabilities of efficient amphibious vehicle will fulfil all the emerging needs of society. Success of every concept largely relies on research and development, though amphibious vehicle is yet to travel a long journey of innovative development, it has shown excellent potentials for future benefits. -

New SESEC Website Will Improve Mutual Understanding of Chinese and European Standardization Systems

PRESS RELEASE Brussels, 2 November 2015 New SESEC website will improve mutual understanding of Chinese and European Standardization Systems The European Standardization Organizations – CEN, CENELEC and ETSI – are pleased to announce the launch of a new website for the third phase of the Seconded European Standardization Expert in China (SESEC) project. The SESEC website (www.sesec.eu) is intended to be a reliable source of accurate information about the Chinese and European Standardization Systems. It should be especially relevant and useful for European companies that wish to do business in China (and vice-versa). The SESEC project is funded and implemented by the three European Standardization Organizations – CEN (European Committee for Standardization), CENELEC (European Committee for Electrotechnical Standardization) and ETSI (European Telecommunications Standards Institute) – together with the European Commission and the European Free Trade Association. The SESEC office in Beijing is managed by Dr Betty XU, who supports exchanges between European standardization stakeholders and their Chinese counterparts. The SESEC project, which was originally launched in 2006, supports the ongoing dialogue between the European Standardization Organizations (ESOs) and the Standardization Administration of the People’s Republic of China (SAC). In particular, it seeks to increase mutual understanding of the Chinese and European standardization systems, to foster cooperation among Chinese and European standardization stakeholders and to encourage -

European and Japanese Standardization Organizations - CEN, CENELEC and JISC - Agree to Strengthen Their Cooperation

NEWS RELEASE - Tokyo, 13 November 2014 European and Japanese standardization organizations - CEN, CENELEC and JISC - agree to strengthen their cooperation Leaders from the European and Japanese standardization organizations have signed a joint Cooperation Agreement in Tokyo today (13 November). The Cooperation Agreement between CEN, CENELEC and JISC provides a new framework for closer collaboration on various aspects of standardization, which will facilitate trade in goods and services between Europe and Japan. The three organizations – CEN (European Committee for Standardization), CENELEC (European Committee for Electrotechnical Standardization) and JISC (Japanese Industrial Standards Committee) – have committed themselves to increase their cooperation on issues of joint interest, in order to enable greater technical alignment of both markets. By strengthening their dialogue and promoting the harmonization of standards at international level, they will help to facilitate trade in goods and services between Europe and Japan, thereby contributing to sustainable growth. The Cooperation Agreement was signed by the Presidents of CEN and CENELEC, respectively Mr Friedrich Smaxwil and Mr Tore Trondvold, and by the President of JISC, Dr Tamotsu Nomakuchi, at a ceremony in Tokyo (Japan), where the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) is holding its 78th General Meeting. The Cooperation Agreement between CEN, CENELEC and JISC provides a common framework to facilitate the sharing of information, the transfer of technical knowledge and the exchange of best practices, as well as mutual support with regard to the work of the international standardization organizations, ISO and IEC. By developing and deepening their cooperation in the field of standardization, CEN, CENELEC and JISC will contribute to overcoming technical barriers to trade and thus facilitating trade between Japan and Europe. -

Tradition and Change Five Athletes Honored Five Careers Celebrated PDS Panther Is Back! Large (14” Body), Soft and Cuddly, Pantherwear with Baby Blue Eyes

HOOL '' ' A Tradition and Change Five Athletes Honored Five Careers Celebrated PDS Panther is Back! Large (14” body), soft and cuddly, PantherWear with baby blue eyes. $40 Its not just to wear it's for cuddling too! Each year the Alumni Board awards a tuition grant to an Upper School Financial Aid recipient who has demonstrated leadership and enthusiasm. All profits from PantherWear sales support the Alumni Scholarship Fund. Show your support! Panther Tote Bag Color: Khaki or white with embroidered black panther. One Size: $18 Adult/Kids Panther Fleeces Navy blue, with embroidered Adult Panther Fleece Vest black panther. Navy blue, with embroidered Adult full zip. Sizes: M, L, XL $65 black panther. Kids 1/4 zip. Sizes: S, M, L $50 Sizes: M, L, XL $50 Adult/Kids Panther Sweatshirts Color: light grey. Adult 100% cotton. Sizes: M, L, XL $40 PDS PantherWear Order Form Kids 50/50. Sizes: S, M, L $24 Ordered by: Name_____ Address City___ State Zip Daytime Phone_ Class Item Size Quantity Price Panther Caps Color: Khaki or white with embroidered black panther. One Size: $18 Subtotal $. Add 6% NJ sales tax on panther $. Shipping O Yes O No (add $8.00 to toal for shipping costs) TOTAL: $. You will be notified when your items are available tor pick-up at the PDS Development PDS Panther T-Shirt Office, Colross. Please make checks payable to Princeton Day School. Color: White with royal and black panthers. Return order form with check to PDS Alumni Office, PO Box 75, The Great Road, Adult Sizes: M, L, XL $18 Princeton, NJ 08542. -

Bates Meets Here Today Prof

Bates College SCARAB The aB tes Student Archives and Special Collections 11-11-1936 The aB tes Student - volume 64 number 14 - November 11, 1936 Bates College Follow this and additional works at: http://scarab.bates.edu/bates_student Recommended Citation Bates College, "The aB tes Student - volume 64 number 14 - November 11, 1936" (1936). The Bates Student. 648. http://scarab.bates.edu/bates_student/648 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Archives and Special Collections at SCARAB. It has been accepted for inclusion in The aB tes Student by an authorized administrator of SCARAB. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "None but a fool is always FOUNDED IN 1873 tnhtnt right." PRICE, 10 CENTS VOL. LXIV- NO. 14. LEWISTON, MAINE, WEDNESDAY. NOVEMBER 11, 1936. Bates Meets Here Today Prof. Bonn Varsity Which Closes Season With Colby Game Today Eight Bates Seniors Will Lectures To Play Their Last Football Politics Club £k£ Chooses Disintegration of The Game For Coach Morey Economic System t t % ,t As Subject Team From Waterville Has Many Good Reserves As Shown By Scores Of "It may be a long time before we I... Jt $. t } come to the end of the breaking up process," said Professor Mor.tz Julius Their State Series Games Bonnt speaking in the Little Theatre, Monday evening, on "The Dis ntegra- tion of the World Economic System," and he expressed the belief that "This Bates Eleven Prepared To Play Their Best breaking up may be nothing but the Game, Since Team Has No Injuries beginning of new formations." Robert York '37, president of Politics Club, introduced the speaker and p: elided ,?■ p v < a a . -

Wfumb and Its Specialist and Continental Federations: the First Quarter Century†

ARTICLE IN PRESS Ultrasound in Med. & Biol., Vol. ●, No. ●, pp. 0000-0000, 2003 Copyright © 2003 World Federation for Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology Printed in the USA. All rights reserved 0301-5629/03/$–see front matter PII: S301-5629(03)00003-6 ● Historical Review THE CONCEPTION, BIRTH AND CHILDHOOD OF WFUMB AND ITS SPECIALIST AND CONTINENTAL FEDERATIONS: THE FIRST QUARTER CENTURY† D. N. WHITE Queen’s University at Kingston Since the discovery of the biological effects of ultrasonic Tissue Diagnosis” in 1955. Even at the seventh meeting energy preceded its use as a diagnostic tool, it was not of the Institute in New York in August 1962 every one of unnatural that the first meetings devoted to medical ul- the ten papers read at the meeting was concerned with trasound were devoted to its therapeutic effects. Its bio- ultrasonic therapy. logical effects first became apparent when, during the The first scientific meeting devoted to medical ul- First World War, Langevin noted that in his attempts to trasound appears to have been the symposium organised develop a technique to detect ultrasonic echoes from by William J. Fry (Fig. 1) of the University of Illinois at submarines, small fish were killed around the generator. Allerton Park in 1952. No proceedings of this historic Wood and Loomis (1927) reported upon the biological meeting were published but its success was such that it effects of ultrasound and Freundlich (1932) suggested its was followed by two further symposia at Allerton Park in use as a diathermic agent which was put into practice June 1955 and June 1962 the proceedings of both of seven years later by Pohlman et al. -

Strategic Forces in Korea Points Regained by Retire in West M^KM

aht "nndu VOL, 3 NO. 30 HAMILTON, BERMUDA SUNDAY, JtiLY 23, 1S50 PRICE 6D Strategic Points Regained By Colony Is Now Deemed Forces In Korea Retire In West Virtually Free Of The aJEW YORK. July 22 (Reuter) Mediterranean Fruit Fly —American and South Korean troops have driven Communist forces out of two strategic points e The Mediterranean fruit fly's "reign of teiror" in Bermuda on the eastern and central Korean is over. fronts but were forced to fall back M^KM |Sh Teaches Chinese In English: on the western sector. News released by Mr. W. R. Evans, Director of Agrtctii- The points captured were Yong- ture, in an interview with The Sunday Royal Gazette, means dpk,- a coastal village, and Yechon, in the region north east of Taejon. that for the first time in nearly 50 years the -fray is clear for On the southwestern front, Sunday School Teacfwr's "Side Line" large-scale cultute in Bermuda of such delicious fiuft as around Chonju, American forces A deficiency in the law of Ber i were reported for the first time muda was pointed out by the peaches, loquats, Surinam cherries and sapodillas. The dis in action against a Communist acting Chief Justice, Dr. the Hon. "Yon want speahee velly good appearance of the fly will give even bananas and sugar apples drive to encircle the entire battle- R. C. Hollis Hallett, on Saturdav English? You go see Alissee, when he decided that a civil suit —wliich occasionally have been attacked by the fry--—a better front from the south.