Syria: Past, Present and Preservation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Revolutions in the Arab World Political, Social and Humanitarian Aspects

REPORT PREPARED WITHIN FRAMEWORK OF THE PROJECT EXPANSION OF THE LIBRARY OF COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION UNIT, CO-FUNDED BY EUROPEAN REFUGEE FUND REVOLUTIONS IN THE ARAB WORLD POLITICAL, SOCIAL AND HUMANITARIAN ASPECTS RADOSŁAW BANIA, MARTA WOŹNIAK, KRZYSZTOF ZDULSKI OCTOBER 2011 COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION UNIT OFFICE FOR FOREIGNERS, POLAND DECEMBER 2011 EUROPEJSKI FUNDUSZ NA RZECZ UCHODŹCÓW REPORT PREPARED WITHIN FRAMEWORK OF THE PROJECT EXPANSION OF THE LIBRARY OF COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION UNIT, CO-FUNDED BY EUROPEAN REFUGEE FUND REVOLUTIONS IN THE ARAB WORLD POLITICAL, SOCIAL AND HUMANITARIAN ASPECTS RADOSŁAW BANIA, MARTA WOŹNIAK, KRZYSZTOF ZDULSKI COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION UNIT OFFICE FOR FOREIGNERS, POLAND OCTOBER 2011 EUROPEAN REFUGEE FUND Revolutions in the Arab World – Political, Social and Humanitarian Aspects Country of Origin Information Unit, Office for Foreigners, 2011 Disclaimer The report at hand is a public document. It has been prepared within the framework of the project “Expansion of the library of Country of Origin Information Unit” no 1/7/2009/EFU, co- funded by the European Refugee Fund. Within the framework of the above mentioned project, COI Unit of the Office for Foreigners commissions reports made by external experts, which present detailed analysis of problems/subjects encountered during refugee/asylum procedures. Information included in these reports originates mainly from publicly available sources, such as monographs published by international, national or non-governmental organizations, press articles and/or different types of Internet materials. In some cases information is based also on experts’ research fieldworks. All the information provided in the report has been researched and evaluated with utmost care. -

Vernacular Tradition and the Islamic Architecture of Bosra, 1992

1 VERNACULAR TRADITION AND THE ISLAMIC ARCHITECTURE OF BOSRA Ph.D. dissertation The Royal Academy of Fine Arts School of Architecture Copenhagen. Flemming Aalund, architect MAA. Copenhagen, April 1991. (revised edition, June 1992) 2 LIST OF CONTENTS : List of maps and drawings......................... 1 List of plates.................................... 4 Preface: Context and purpose .............................. 7 Contents.......................................... 8 Previous research................................. 9 Acknowledgements.................................. 11 PART I: THE PHYSICAL AND HISTORIC SETTING The geographical setting.......................... 13 Development of historic townscape and buildings... 16 The Islamic town.................................. 19 The Islamic renaissance........................... 21 PART II: THE VERNACULAR BUILDING TRADITION Introduction...................................... 27 Casestudies: - Umm az-Zetun.................................... 29 - Mu'arribeh...................................... 30 - Djemmerin....................................... 30 - Inkhil.......................................... 32 General features: - The walling: construction and materials......... 34 - The roofing..................................... 35 - The plan and structural form.................... 37 - The sectional form: the iwan.................... 38 - The plan form: the bayt......................... 39 conclusion........................................ 40 PART III: CATALOGUE OF ISLAMIC MONUMENTS IN BOSRA Introduction..................................... -

Weekly Conflict Summary | 3 – 9 June 2019

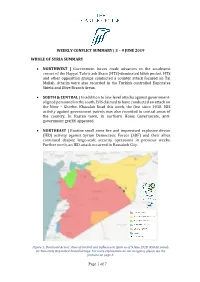

WEEKLY CONFLICT SUMMARY | 3 – 9 JUNE 2019 WHOLE OF SYRIA SUMMARY • NORTHWEST | Government forces made advances in the southwest corner of the Hayyat Tahrir ash Sham (HTS)-dominated Idleb pocket. HTS and other opposition groups conducted a counter attack focused on Tal Mallah. Attacks were also recorded in the Turkish-controlled Euphrates Shield and Olive Branch Areas. • SOUTH & CENTRAL | In addition to low-level attacks against government- aligned personnel in the south, ISIS claimed to have conducted an attack on the Nimr – Gherbet Khazalah Road this week, the first since 2018. ISIS activity against government patrols was also recorded in central areas of the country. In Rastan town, in northern Homs Governorate, anti- government graffiti appeared. • NORTHEAST | Routine small arms fire and improvised explosive device (IED) activity against Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) and their allies continued despite large-scale security operations in previous weeks. Further north, an IED attack occurred in Hassakeh City. Figure 1: Dominant Actors’ Area of Control and Influence in Syria as of 9 June 2019. NSOAG stands for Non-state Organized Armed Groups. For more explanation on our mapping, please see the footnote on page 2. Page 1 of 7 WEEKLY CONFLICT SUMMARY | 3 – 9 JUNE 2019 NORTHWEST SYRIA1 This week, Government of Syria (GOS) forces made advances in the southwest corner of the Hayyat Tahrir ash Sham (HTS)-dominated Idleb enclave. On 3 June, GOS Tiger Forces captured al Qasabieyh town to the north of Kafr Nabuda, before turning west and taking Qurutiyah village a day later. Currently, fighting is concentrated around Qirouta village. However, late on 5 June, HTS and the Turkish-Backed National Liberation Front (NLF) launched a major counter offensive south of Kurnaz town after an IED detonated at a fortified government location. -

International Swiss Architect Pierre De Meuron Visit Day

Draft proposal – International Swiss Architect Pierre De Meuron visit Day one: Wednesday Sep 29 / arrival – Damascus ‐ Receiving (and issuing visas) at Damascus airport ‐ Checking in the hotel ( I recommend the Art House or the Four Seasons). ‐ Short rest ‐ Meeting at the hotel ‐ Short car tour in the city ‐ Dinner at mount Qasyoun Day two: Thursday Sep 30 / Damascus ‐ National museum and Taqiyya Sulaimaniyya ‐ Old city ‐ Dinner at Narenj Rest. In the old city Day three Friday Oct 1 / Bosra and southern region ‐ From Damascus to Bosra (through Shahba and Qanawat) ‐ Bosra tour including lunch ‐ Brom Bosra back to Damascus (through Daraa) ‐ Dinner at Art House in Damascus Day four: Saturday Oct 2 / Palmyra (accompanied by professional designated guide) ‐ From Damascus to Palmyra ‐ Palmyra tour ‐ Dinner and stay in Palmyra (recommended at AL‐Cham hotel) Day five: Sunday Oct 3 / middle region ‐ From Palmyra to Hamah through Homs (visit Hamah museum) ‐ From Hamah to Aleppo (through Ebla) ‐ Dinner and stay in Aleppo (recommended at Al Mansouri in the old city or in the Sheraton) Day six: Monday Oct 4 / Aleppo – north region ‐ Old city and citadel of Aleppo ‐ St. Simon (and parts of the dead cities) ‐ Back to Aleppo Day seven: Tuesday Oct 5 ‐ Back to Damascus (via plane) ‐ Free day in Damascus region (available for the intended potential meeting) Day eight: Wednesday Oct 6 ‐ Available for the meeting ‐ Departure Note: an alternative way from Homs to Aleppo is not to go directly north through Hamah but to go north west through the coastal region visiting some important medieval castles, and Phoenician sites as well as spectacular scenery, all the way to Lattakia through Tartous and then from Lattakia to Aleppo through Hellenistic Aphamea and classical (Byzantine) dead cites. -

The Historical Earthquakes of Syria: an Analysis of Large and Moderate Earthquakes from 1365 B.C

ANNALS OF GEOPHYSICS, VOL. 48, N. 3, June 2005 The historical earthquakes of Syria: an analysis of large and moderate earthquakes from 1365 B.C. to 1900 A.D. Mohamed Reda Sbeinati (1), Ryad Darawcheh (1) and Mikhail Mouty (2) (1) Department of Geology, Atomic Energy Commission of Syria, Damascus, Syria (2) Department of Geology, Faculty of Science, Damascus University, Damascus, Syria Abstract The historical sources of large and moderate earthquakes, earthquake catalogues and monographs exist in many depositories in Syria and European centers. They have been studied, and the detailed review and analysis re- sulted in a catalogue with 181 historical earthquakes from 1365 B.C. to 1900 A.D. Numerous original documents in Arabic, Latin, Byzantine and Assyrian allowed us to identify seismic events not mentioned in previous works. In particular, detailed descriptions of damage in Arabic sources provided quantitative information necessary to re-evaluate past seismic events. These large earthquakes (I0>VIII) caused considerable damage in cities, towns and villages located along the northern section of the Dead Sea fault system. Fewer large events also occurred along the Palmyra, Ar-Rassafeh and the Euphrates faults in Eastern Syria. Descriptions in original sources doc- ument foreshocks, aftershocks, fault ruptures, liquefaction, landslides, tsunamis, fires and other damages. We present here an updated historical catalogue of 181 historical earthquakes distributed in 4 categories regarding the originality and other considerations, we also present a table of the parametric catalogue of 36 historical earth- quakes (table I) and a table of the complete list of all historical earthquakes (181 events) with the affected lo- cality names and parameters of information quality and completeness (table II) using methods already applied in other regions (Italy, England, Iran, Russia) with a completeness test using EMS-92. -

Bosra and the South

chapter 7 Bosra and the South Bosra Roman Bozrah . was a beautiful city, with long straight avenues and spacious thoroughfares; but the Saracens built their miserable little shops and quaint irregular houses along the sides of the streets, out and in, here and there, as fancy or funds directed; and they thus converted the stately Roman capital, as they did Damascus and Antioch, into a labyrinth of narrow, crooked, gloomy lanes.[1] [1865] Bosra,[2] 140km south of Damascus, the main town in the Hauran, and a site investigated by today’s archaeologists,1 was in ancient times the centre of a rich and prosperous agricultural region, and well endowded with monuments including temples, theatre, hippodrome and amphitheatre, the main area pro- tected by walls. Its towers were visible for miles around,[3] but some travel- lers believed it had been more affected by earthquakes than other sites.[4] The imprint of the hippodrome may be seen from the Ayyubid Citadel, itself built round the Roman theatre, and presumably using very large quantities of blocks from the amphitheatre, barely 30m distant. This is only known to us from recent excavation, and no early travellers mention it, so either the Ayyubid builders must have stripped it to the foundations, or earlier inhabitants must have used its blocks for churches and houses. In any case, by the 20th century, the site was covered in modern houses and gardens. Since amphitheatres were so often turned into fortresses in post-Roman times, it is likely the structure had been partly robbed out well before the Ayyubids. -

From Daraa to Damascus: Regional and Temporal Protest Variation in Syria

From Daraa to Damascus: Regional and Temporal Protest Variation in Syria by Shena L. Cavallo B.A. International Relations and Spanish, Duquesne University, 2007 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Graduate School of Public and International Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of M.A International Development University of Pittsburgh 2012 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH Graduate School of Public and International Affairs This thesis was presented by Shena L. Cavallo It was defended on May 23, 2012 and approved by M. Müge Kokten-Finkel, PhD, Assistant Professor Ilia Murtazashvili, PhD, Assistant Professor Paul J. Nelson, PhD, Associate Professor Thesis Director: Luke N. Condra, PhD, Assistant Professor ii Copyright © by Shena L. Cavallo 2012 iii From Daraa to Damascus: Regional and Temporal Protest Variation in Syria Shena Cavallo, MID University of Pittsburgh, 2012 When protest erupted in Syria on March 2011, there was considerable analysis seeking to explain the initial display of collective action. While this initial showing of dissent caught some off-guard, what was more remarkable is how the protest movement managed to endure, well over a year, despite policies of severe repression, a lack of established opposition organizations, and a lack of regime defections. This paper seeks to explore which factors have sustained the protest movement, as well as the role of these factors at different stages in the ‘protest wave’ and the relationship these variables share with region- specific waves of protest. I hypothesize that more traditional approaches to understanding protest longevity must be expanded in order to help explain contemporary events of protest, particularly in authoritarian contexts. -

ASOR Syrian Heritage Initiative (SHI): Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria1 NEA-PSHSS-14-001

ASOR Syrian Heritage Initiative (SHI): Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria1 NEA-PSHSS-14-001 Weekly Report 9 – October 6, 2014 MiChael D. Danti, Cheikhmous Ali, Jesse Casana, and Kurt W. PresCott Heritage Timeline October 5, 2014 APSA posted Syria’s Cultural Heritage: APSA-report-01 September 2014. This report includes the individual APSA reports detailed in SHI Weekly Reports 3–9. http://www.apsa2011.Com/index.php/en/apsa- rapports/987-apsa-report-september-2014.html October 3, 2014 APSA posted photos from journalist Shady Hulwe showing the total destruCtion of the Khusruwiye Madrasa and Mosque and the damage to the Khan al-Shouna in the UNESCO World Heritage Site, AnCient City of Aleppo. SHI InCident Report SHI14-054. • The New York Times published “Antiquities Lost, Casualties of War. In Syria and Iraq, Trying to ProteCt a Heritage at Risk,” by Graham Bowley. http://www.nytimes.Com/2014/10/05/arts/design/in-syria- and-iraq-trying-to-proteCt-a-heritage-at-risk.html?_r=0 October 2, 2014 APSA posted several photographs taken by Syrian journalist Shady Hulwe showing damage to the Hittite temple of the weather-god on the Aleppo Citadel in the UNESCO World Heritage Site, AnCient City of Aleppo. SHI InCident Report SHI14-039. October 1, 2014 APSA posted a video to their website showing a fire at the Great Umayyad Mosque in the UNESCO World Heritage Site, AnCient City of Aleppo. SHI InCident Report SHI14-040. http://www.apsa2011.Com/index.php/en/provinces/aleppo/great- umayyad-mosque/975-alep-omeyyades-2.html September 30, 2014 DGAM released Initial Damages Assessment for Syrian Cultural Heritage During the Crises covering the period July 7, 2014 to September 30, 2014. -

South Syria Torn Between a Grim Fate of Forced Displacement and Starvation Or an Almost Certain Death by Falling Back Into Syrian Regime’S Control

South Syria Torn between a Grim Fate of Forced Displacement and Starvation or an Almost Certain Death by Falling Back into Syrian Regime’s Control The US Abandons its Commitments in South Syria Agreement Tuesday, July 31, 2018 1 snhr [email protected] www.sn4hr.org The Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR), founded in June 2011, is a non-governmental, independent group that is considered a primary source for the OHCHR on all death toll-related analyses in Syria. Contents I. Introduction and Methodology II. The US Administration is Directly Responsible for the South Syria Travesty III. Toll of Most Notable Violations in the aftermath of the Syrian-Russian Offensive on South Syria IV. South Syria is another Eastern Ghouta Scenario V. The Syrian Regime Violates Russia-Sponsored Agreements VI. Forced Displacement Enforced by the Barbarian Offensive, Followed by Coerced Evacuation Agreements VII. Civilians in Hawd al Yarmouk Area, Trapped between the Syrian Regime’s Terrorism and ISIS’s VIII. Most Notable Violations by Russian-Syrian Alliance Forces in the South Region IX. Legal Description and Recommendations I. Introduction and Methodology The region of south Syria has sealed the complete collapse of the so-called “the de-es- calation zone agreements”, yet another item in a long list of Security Council’s failures as the Security Council didn’t maintain any form of security or peace in Syria or prevent the displacement of hundreds of thousands in south Syria. This crippling powerlessness was deliberately staged and repeated over the course -

Building Legitimacy Under Bombs: Syrian Local Revolutionary Governance’S Quest for Trust and Peace

BUILDING LEGITIMACY UNDER BOMBS: SYRIAN LOCAL REVOLUTIONARY GOVERNANCE’S QUEST FOR TRUST AND PEACE Nour Salameh ADVERTIMENT. L'accés als continguts d'aquesta tesi doctoral i la seva utilització ha de respectar els drets de la persona autora. Pot ser utilitzada per a consulta o estudi personal, així com en activitats o materials d'investigació i docència en els termes establerts a l'art. 32 del Text Refós de la Llei de Propietat Intel·lectual (RDL 1/1996). Per altres utilitzacions es requereix l'autorització prèvia i expressa de la persona autora. En qualsevol cas, en la utilització dels seus continguts caldrà indicar de forma clara el nom i cognoms de la persona autora i el títol de la tesi doctoral. No s'autoritza la seva reproducció o altres formes d'explotació efectuades amb finalitats de lucre ni la seva comunicació pública des d'un lloc aliè al servei TDX. Tampoc s'autoritza la presentació del seu contingut en una finestra o marc aliè a TDX (framing). Aquesta reserva de drets afecta tant als continguts de la tesi com als seus resums i índexs. ADVERTENCIA. El acceso a los contenidos de esta tesis doctoral y su utilización debe respetar los derechos de la persona autora. Puede ser utilizada para consulta o estudio personal, así como en actividades o materiales de investigación y docencia en los términos establecidos en el art. 32 del Texto Refundido de la Ley de Propiedad Intelectual (RDL 1/1996). Para otros usos se requiere la autorización previa y expresa de la persona autora. En cualquier caso, en la utilización de sus contenidos se deberá indicar de forma clara el nombre y apellidos de la persona autora y el título de la tesis doctoral. -

Syria's Cultural Heritage in Conflict

DAMAGE TO THE SOUL: SYRIA’S CULTURAL HERITAGE IN CONFLICT 1 16 MAY 2012 Emma Cunliffe, Durham University, and “Damage to the heritage of the country is damage to the soul of its people and its identity” Irina Bokova, Director-General of UNESCO 2 As the focus of this report is the cultural heritage of Syria, the massive loss of human life during the conflict is not mentioned in the body of the report. However, this heritage was built by the ancestors of those who have gone, and those who remain. It is remembered by them, and cared for by them, to be Patrimoine Syriensed on to their descendants and to the world. History starts and ends with memory, and the Patrimoine Syrient is carried in the shared memory of the present. One cannot exist without the other. I feel the only place to start this report is to express our deep sadness at the loss of life, our sympathy to those who have suffered, and extend our sincerest condolences to all those who have lost friends and loved ones. With thanks to the Arts and Humanities Research Council, Trevelyan Collage Durham University, and the Global Heritage Fund Fellowship Page 2 of 55 Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................ 4 Background ................................................................................................................................................. 4 Information Sources and Copyright ................................................................................................... -

Ictj Briefing

ictj briefing May 2019 An Uncertain Homecoming Views of Syrian Refugees in Jordan on Return, Justice, and About the Research Project Coexistence This briefing paper summarizes the findings of a longer research report entitled An Introduction Uncertain Homecoming: Views of Syrian Refugees in Jordan on The protracted conflict in Syria continues to have serious and widespread ill effects on Return, Justice, and Coexistence. the lives of Syrian individuals, households, and communities. The majority of the Syr- Through in-depth qualitative ian population has been tremendously affected by the war, including women, children, interviews with Syrian refugees and elderly, with millions having been forced to leave behind their life projects, memo- in Jordan, the study explores the ries, hopes, and dreams in search of protection and safety. For Syrian refugees, very challenges that Syrians will face in returning home and rebuilding basic needs, such as food, health services, education, water, utilities, and sanitation, had relationships once the conflict in become unattainable and staying alive meant leaving their lives behind to escape the their country ends and the role constant risk of shelling, artillery strikes, abduction, enforced disappearance, exploitation, that justice can play in these forced displacement, and violence. Most have sought refuge in neighboring countries, processes. The study stresses the including Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey, and beyond the region, in Europe and elsewhere. importance of amplifying the voices of Syrian refugees, calling This briefing paper presents findings from a study exploring the impact of the conflict and attention to their stories, and displacement on Syrian refugees in Jordan and the potential for justice and coexistence incorporating them in discussions among Syrian communities.