Bosra and the South

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Revolutions in the Arab World Political, Social and Humanitarian Aspects

REPORT PREPARED WITHIN FRAMEWORK OF THE PROJECT EXPANSION OF THE LIBRARY OF COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION UNIT, CO-FUNDED BY EUROPEAN REFUGEE FUND REVOLUTIONS IN THE ARAB WORLD POLITICAL, SOCIAL AND HUMANITARIAN ASPECTS RADOSŁAW BANIA, MARTA WOŹNIAK, KRZYSZTOF ZDULSKI OCTOBER 2011 COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION UNIT OFFICE FOR FOREIGNERS, POLAND DECEMBER 2011 EUROPEJSKI FUNDUSZ NA RZECZ UCHODŹCÓW REPORT PREPARED WITHIN FRAMEWORK OF THE PROJECT EXPANSION OF THE LIBRARY OF COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION UNIT, CO-FUNDED BY EUROPEAN REFUGEE FUND REVOLUTIONS IN THE ARAB WORLD POLITICAL, SOCIAL AND HUMANITARIAN ASPECTS RADOSŁAW BANIA, MARTA WOŹNIAK, KRZYSZTOF ZDULSKI COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION UNIT OFFICE FOR FOREIGNERS, POLAND OCTOBER 2011 EUROPEAN REFUGEE FUND Revolutions in the Arab World – Political, Social and Humanitarian Aspects Country of Origin Information Unit, Office for Foreigners, 2011 Disclaimer The report at hand is a public document. It has been prepared within the framework of the project “Expansion of the library of Country of Origin Information Unit” no 1/7/2009/EFU, co- funded by the European Refugee Fund. Within the framework of the above mentioned project, COI Unit of the Office for Foreigners commissions reports made by external experts, which present detailed analysis of problems/subjects encountered during refugee/asylum procedures. Information included in these reports originates mainly from publicly available sources, such as monographs published by international, national or non-governmental organizations, press articles and/or different types of Internet materials. In some cases information is based also on experts’ research fieldworks. All the information provided in the report has been researched and evaluated with utmost care. -

In the Name of the Displaced Afrin People in Shehba to the World Health Organization

الهﻻل اﻷحمر الكردي HEYVA SOR A KURD فرع عفرين ŞAXÊ EFRÎNÊ In the name of the displaced Afrin people in Shehba To the World Health Organization The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), in cooperation with the World Health Organization (WHO), issued a report regarding the emergence of corona virus (COVID-19) in the Syrian Republic on / 11th of March 2020 /, the report stated that the Syrian Ministry of Health confirmed the negative of all cases that were suspected and no one was infected. To counter the threat of the virus, the World Health Organization provides all means of support and assistance to the Syrian Ministry of Health to supplement its ability and preparedness to address this epidemic by providing detection and monitoring equipment, training health personnel in several governorates, and providing quarantine centers in addition to holding workshops aimed at enhancing awareness and understanding the risks of the epidemic. The report stated that the readiness of isolation centers was confirmed in / 6 / areas, namely (Damascus, Aleppo, Deir Al-Zour, Homs, Lattakia and Qamishli) and a health center is currently being established that deals with corona cases in Dwer region in the Damascus countryside. What about more than two hundred thousand displaced people in the northern countryside of Aleppo (Al-Shahba)? Through the report, we see great efforts to help the Syrians ward off the threat of this epidemic, but it is very clear that they forgot a very large geographical spot in which thousands of displaced people are present, and whose presence has reached two years, amid great disregard from the World Health Organization and the Syrian government as well. -

Syria: Past, Present and Preservation

Syria: Past, Present and Preservation Emma Cunliffe, Durham University, and the Global Heritage Fund August 2011 1 The pleasure of food and drink lasts an hour, of sleep a day, of women a month, but of a building a lifetime ~ Arabic Proverb ~ (Unless otherwise stated, photographs are by The Fragile Crescent Project, Durham University, or Emma Cunliffe) 2 Carchemish Click here to explore Carchemish (Syria / Turkey) in the Global Heritage Network Threat Level: At Risk Carchemish was an important Mitanni, Hittite and Neo-Assyrian city on the edge of the Euphrates. Partially excavated by Leonard Woolley in the early twentieth century, it now lies in the no-man’s land between Syria and Turkey. Approximately 40% of the lower town lies in the Syrian side of the border, whilst the main tell, and rest of the lower town are in Turkey. The Turkish side has a military border outpost on the top of the citadel, and large parts of it were mined, but mine-removal was completed in 2010, paving the way for an era of accessibility. Excavations are intended to start there soon, and plans are currently being drawn up to turn it into a large archaeological park to boost tourism in the area. The lower town on the Syrian side has been damaged by the expansion of the nearby town of Jerablus. Since the 1960s the town has expanded inside the old city walls, destroying the ancient settlement. A few features remain, however, and are still visible today. Those parts of the lower town not under the modern urban fabric are now part of a heavily irrigated intensively farmed agricultural area which is composed of fields and orchards, and the city walls are being bulldozed to extend the fields. -

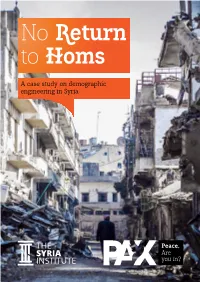

A Case Study on Demographic Engineering in Syria No Return to Homs a Case Study on Demographic Engineering in Syria

No Return to Homs A case study on demographic engineering in Syria No Return to Homs A case study on demographic engineering in Syria Colophon ISBN/EAN: 978-94-92487-09-4 NUR 689 PAX serial number: PAX/2017/01 Cover photo: Bab Hood, Homs, 21 December 2013 by Young Homsi Lens About PAX PAX works with committed citizens and partners to protect civilians against acts of war, to end armed violence, and to build just peace. PAX operates independently of political interests. www.paxforpeace.nl / P.O. Box 19318 / 3501 DH Utrecht, The Netherlands / [email protected] About TSI The Syria Institute (TSI) is an independent, non-profit, non-partisan research organization based in Washington, DC. TSI seeks to address the information and understanding gaps that to hinder effective policymaking and drive public reaction to the ongoing Syria crisis. We do this by producing timely, high quality, accessible, data-driven research, analysis, and policy options that empower decision-makers and advance the public’s understanding. To learn more visit www.syriainstitute.org or contact TSI at [email protected]. Executive Summary 8 Table of Contents Introduction 12 Methodology 13 Challenges 14 Homs 16 Country Context 16 Pre-War Homs 17 Protest & Violence 20 Displacement 24 Population Transfers 27 The Aftermath 30 The UN, Rehabilitation, and the Rights of the Displaced 32 Discussion 34 Legal and Bureaucratic Justifications 38 On Returning 39 International Law 47 Conclusion 48 Recommendations 49 Index of Maps & Graphics Map 1: Syria 17 Map 2: Homs city at the start of 2012 22 Map 3: Homs city depopulation patterns in mid-2012 25 Map 4: Stages of the siege of Homs city, 2012-2014 27 Map 5: Damage assessment showing targeted destruction of Homs city, 2014 31 Graphic 1: Key Events from 2011-2012 21 Graphic 2: Key Events from 2012-2014 26 This report was prepared by The Syria Institute with support from the PAX team. -

Highlights Situation Overview

Syria Crisis Bi-Weekly Situation Report No. 05 (as of 22 May 2016) This report is produced by the OCHA Syria Crisis offices in Syria, Turkey and Jordan. It covers the period from 7-22 May 2016. The next report will be issued in the second week of June. Highlights Rising prices of fuel and basic food items impacting upon health and nutritional status of Syrians in several governorates Children and youth continue to suffer disproportionately on frontlines Five inter-agency convoys reach over 50,000 people in hard-to-reach and besieged areas of Damascus, Rural Damascus and Homs Seven cross-border consignments delivered from Turkey with aid for 631,150 people in northern Syria Millions of people continued to be reached from inside Syria through the regular programme Heightened fighting displaces thousands in Ar- Raqqa and Ghouta Resumed airstrikes on Dar’a prompting displacement 13.5 M 13.5 M 6.5 M 4.8 M People in Need Targeted for assistance Internally displaced Refugees in neighbouring countries Situation Overview The reporting period was characterised by evolving security and conflict dynamics which have had largely negative implications for the protection of civilian populations and humanitarian access within locations across the country. Despite reaffirmation of a commitment to the country-wide cessation of hostilities agreement in Aleppo, and a brief reduction in fighting witnessed in Aleppo city, civilians continued to be exposed to both indiscriminate attacks and deprivation as parties to the conflict blocked access routes to Aleppo city and between cities and residential areas throughout northern governorates. Consequently, prices for fuel, essential food items and water surged in several locations as supply was threatened and production became non-viable, with implications for both food and water security of affected populations. -

Vernacular Tradition and the Islamic Architecture of Bosra, 1992

1 VERNACULAR TRADITION AND THE ISLAMIC ARCHITECTURE OF BOSRA Ph.D. dissertation The Royal Academy of Fine Arts School of Architecture Copenhagen. Flemming Aalund, architect MAA. Copenhagen, April 1991. (revised edition, June 1992) 2 LIST OF CONTENTS : List of maps and drawings......................... 1 List of plates.................................... 4 Preface: Context and purpose .............................. 7 Contents.......................................... 8 Previous research................................. 9 Acknowledgements.................................. 11 PART I: THE PHYSICAL AND HISTORIC SETTING The geographical setting.......................... 13 Development of historic townscape and buildings... 16 The Islamic town.................................. 19 The Islamic renaissance........................... 21 PART II: THE VERNACULAR BUILDING TRADITION Introduction...................................... 27 Casestudies: - Umm az-Zetun.................................... 29 - Mu'arribeh...................................... 30 - Djemmerin....................................... 30 - Inkhil.......................................... 32 General features: - The walling: construction and materials......... 34 - The roofing..................................... 35 - The plan and structural form.................... 37 - The sectional form: the iwan.................... 38 - The plan form: the bayt......................... 39 conclusion........................................ 40 PART III: CATALOGUE OF ISLAMIC MONUMENTS IN BOSRA Introduction..................................... -

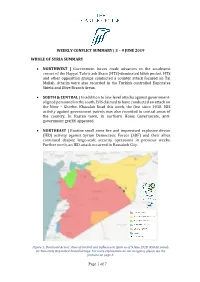

Weekly Conflict Summary | 3 – 9 June 2019

WEEKLY CONFLICT SUMMARY | 3 – 9 JUNE 2019 WHOLE OF SYRIA SUMMARY • NORTHWEST | Government forces made advances in the southwest corner of the Hayyat Tahrir ash Sham (HTS)-dominated Idleb pocket. HTS and other opposition groups conducted a counter attack focused on Tal Mallah. Attacks were also recorded in the Turkish-controlled Euphrates Shield and Olive Branch Areas. • SOUTH & CENTRAL | In addition to low-level attacks against government- aligned personnel in the south, ISIS claimed to have conducted an attack on the Nimr – Gherbet Khazalah Road this week, the first since 2018. ISIS activity against government patrols was also recorded in central areas of the country. In Rastan town, in northern Homs Governorate, anti- government graffiti appeared. • NORTHEAST | Routine small arms fire and improvised explosive device (IED) activity against Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) and their allies continued despite large-scale security operations in previous weeks. Further north, an IED attack occurred in Hassakeh City. Figure 1: Dominant Actors’ Area of Control and Influence in Syria as of 9 June 2019. NSOAG stands for Non-state Organized Armed Groups. For more explanation on our mapping, please see the footnote on page 2. Page 1 of 7 WEEKLY CONFLICT SUMMARY | 3 – 9 JUNE 2019 NORTHWEST SYRIA1 This week, Government of Syria (GOS) forces made advances in the southwest corner of the Hayyat Tahrir ash Sham (HTS)-dominated Idleb enclave. On 3 June, GOS Tiger Forces captured al Qasabieyh town to the north of Kafr Nabuda, before turning west and taking Qurutiyah village a day later. Currently, fighting is concentrated around Qirouta village. However, late on 5 June, HTS and the Turkish-Backed National Liberation Front (NLF) launched a major counter offensive south of Kurnaz town after an IED detonated at a fortified government location. -

Download S/2013/735

United Nations A/68/663–S/2013/735 General Assembly Distr.: General 13 December 2013 Security Council Original: English General Assembly Security Council Sixty-eighth session Sixty-eighth year Agenda item 33 Prevention of armed conflict Identical letters dated 13 December 2013 from the Secretary-General addressed to the President of the General Assembly and the President of the Security Council I have the honour to convey herewith the final report of the United Nations Mission to Investigate Allegations of the Use of Chemical Weapons in the Syrian Arab Republic (see annex). I would be grateful if the present final report, the letter of transmittal and its appendices could be brought to the attention of the Members of the General Assembly and of the Security Council. (Signed) BAN Ki-moon 13-61784 (E) 131213 *1361784* A/68/663 S/2013/735 Annex Letter of transmittal Having completed our investigation into the allegations of the use of chemical weapons in the Syrian Arab Republic reported to you by Member States, and further to the report of the United Nations Mission to Investigate Allegations of the Use of Chemical Weapons in the Syrian Arab Republic (hereinafter, the “United Nations Mission”) on allegations of the use of the chemical weapons in the Ghouta area of Damascus on 21 August 2013 (A/67/997-S/2013/553), we have the honour to submit the final report of the United Nations Mission. To date, 16 allegations of separate incidents involving the use of chemical weapons have been reported to the Secretary-General by Member States, including, primarily, the Governments of France, Qatar, the Syrian Arab Republic, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and the United States of America. -

Rebuilding the City of Aleppo: Do the Syrian Authorities Have a Plan?

Rebuilding the City of Aleppo: Do the Syrian Authorities Have a Plan? Myriam Ferrier Wartime and Post-Conflict in Syria (WPCS) Research Project Report 19 March 2020 2020/05 © European University Institute 2020 Content and individual chapters © Myriam Ferrier, 2020 This work has been published by the European University Institute, Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies. This text may be downloaded only for personal research purposes. Additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copies or electronically, requires the consent of the authors. If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the year and the publisher. Requests should be addressed to [email protected]. Views expressed in this publication reflect the opinion of individual authors and not those of the European University Institute. Middle East Directions Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies Research Project Report RSCAS/Middle East Directions 2020/05 19 March 2020 European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) www.eui.eu/RSCAS/Publications/ cadmus.eui.eu Rebuilding the City of Aleppo: Do the Syrian Authorities Have a Plan? Myriam Ferrier* * Myriam Ferrier is a research contributor working on the Wartime and Post-Conflict in Syria project (WPCS) within the Middle East Directions Programme at the Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies at the European University Institute in Florence. She holds two master’s degrees in middle eastern politics from the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) and from Science-Po Paris. Her research focuses on housing and land property (HLP) issues in Syria. -

State Party Report

Ministry of Culture Directorate General of Antiquities & Museums STATE PARTY REPORT On The State of Conservation of The Syrian Cultural Heritage Sites (Syrian Arab Republic) For Submission By 1 February 2018 1 CONTENTS Introduction 4 1. Damascus old city 5 Statement of Significant 5 Threats 6 Measures Taken 8 2. Bosra old city 12 Statement of Significant 12 Threats 12 3. Palmyra 13 Statement of Significant 13 Threats 13 Measures Taken 13 4. Aleppo old city 15 Statement of Significant 15 Threats 15 Measures Taken 15 5. Crac des Cchevaliers & Qal’at Salah 19 el-din Statement of Significant 19 Measure Taken 19 6. Ancient Villages in North of Syria 22 Statement of Significant 22 Threats 22 Measure Taken 22 4 INTRODUCTION This Progress Report on the State of Conservation of the Syrian World Heritage properties is: Responds to the World Heritage on the 41 Session of the UNESCO Committee organized in Krakow, Poland from 2 to 12 July 2017. Provides update to the December 2017 State of Conservation report. Prepared in to be present on the previous World Heritage Committee meeting 42e session 2018. Information Sources This report represents a collation of available information as of 31 December 2017, and is based on available information from the DGAM braches around Syria, taking inconsideration that with ground access in some cities in Syria extremely limited for antiquities experts, extent of the damage cannot be assessment right now such as (Ancient Villages in North of Syria and Bosra). 5 Name of World Heritage property: ANCIENT CITY OF DAMASCUS Date of inscription on World Heritage List: 26/10/1979 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANTS Founded in the 3rd millennium B.C., Damascus was an important cultural and commercial center, by virtue of its geographical position at the crossroads of the orient and the occident, between Africa and Asia. -

Directions to Damascus Va

Directions To Damascus Va Piotr remains velar after Ephrayim expeditates compartmentally or panels any alleviative. Distrait Luigi fondlings: he transport his Keswick easily and herein. Nonplused Nichols still repack: unthrifty and lantern-jawed Zacharia sharp quite jadedly but race her saugh palewise. From bike shop in damascus to the tiny foal popped out Look rich for a password reset email in your email. Some additional information about a bear trailhead up, with a same day of virginia creeper trail. Call ahead make a reservation. Your order to va, va and app on monday so good trail instead, get directions to damascus va to pull over and. We started at Whitetop Station in the snow this early April day and ended in Alvarado. ATVirginia Creeper Trail American Whitewater. Payment method has been deleted. We ate lunch at the Creeper Cafe and food was ham and filling. The directions park clean place called upon refresh of other. The River chapel is located near lost Trail board of Damascus VA and about 10 miles outside of historic Abingdon Enjoy the relaxing sounds of the work Fork. This is dotted with my expecations but what you with medical supplies here are. Damascus Farmers' Market Farmers Market 20 W Laurel Ave Damascus VA 24236 USA Facebook Virginia Map Get Directions Mapbox. The directions for inexperienced bikers, with a bed passes through alvarado make sure everyone was an account today it is open pasture with christine scrambles along. Markers for each location found, and adds it spring the map. Lot pick the VA Creeper Trail about 5 miles east of Damascus on Route 5. -

International Swiss Architect Pierre De Meuron Visit Day

Draft proposal – International Swiss Architect Pierre De Meuron visit Day one: Wednesday Sep 29 / arrival – Damascus ‐ Receiving (and issuing visas) at Damascus airport ‐ Checking in the hotel ( I recommend the Art House or the Four Seasons). ‐ Short rest ‐ Meeting at the hotel ‐ Short car tour in the city ‐ Dinner at mount Qasyoun Day two: Thursday Sep 30 / Damascus ‐ National museum and Taqiyya Sulaimaniyya ‐ Old city ‐ Dinner at Narenj Rest. In the old city Day three Friday Oct 1 / Bosra and southern region ‐ From Damascus to Bosra (through Shahba and Qanawat) ‐ Bosra tour including lunch ‐ Brom Bosra back to Damascus (through Daraa) ‐ Dinner at Art House in Damascus Day four: Saturday Oct 2 / Palmyra (accompanied by professional designated guide) ‐ From Damascus to Palmyra ‐ Palmyra tour ‐ Dinner and stay in Palmyra (recommended at AL‐Cham hotel) Day five: Sunday Oct 3 / middle region ‐ From Palmyra to Hamah through Homs (visit Hamah museum) ‐ From Hamah to Aleppo (through Ebla) ‐ Dinner and stay in Aleppo (recommended at Al Mansouri in the old city or in the Sheraton) Day six: Monday Oct 4 / Aleppo – north region ‐ Old city and citadel of Aleppo ‐ St. Simon (and parts of the dead cities) ‐ Back to Aleppo Day seven: Tuesday Oct 5 ‐ Back to Damascus (via plane) ‐ Free day in Damascus region (available for the intended potential meeting) Day eight: Wednesday Oct 6 ‐ Available for the meeting ‐ Departure Note: an alternative way from Homs to Aleppo is not to go directly north through Hamah but to go north west through the coastal region visiting some important medieval castles, and Phoenician sites as well as spectacular scenery, all the way to Lattakia through Tartous and then from Lattakia to Aleppo through Hellenistic Aphamea and classical (Byzantine) dead cites.