Rebuilding the City of Aleppo: Do the Syrian Authorities Have a Plan?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Name of the Displaced Afrin People in Shehba to the World Health Organization

الهﻻل اﻷحمر الكردي HEYVA SOR A KURD فرع عفرين ŞAXÊ EFRÎNÊ In the name of the displaced Afrin people in Shehba To the World Health Organization The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), in cooperation with the World Health Organization (WHO), issued a report regarding the emergence of corona virus (COVID-19) in the Syrian Republic on / 11th of March 2020 /, the report stated that the Syrian Ministry of Health confirmed the negative of all cases that were suspected and no one was infected. To counter the threat of the virus, the World Health Organization provides all means of support and assistance to the Syrian Ministry of Health to supplement its ability and preparedness to address this epidemic by providing detection and monitoring equipment, training health personnel in several governorates, and providing quarantine centers in addition to holding workshops aimed at enhancing awareness and understanding the risks of the epidemic. The report stated that the readiness of isolation centers was confirmed in / 6 / areas, namely (Damascus, Aleppo, Deir Al-Zour, Homs, Lattakia and Qamishli) and a health center is currently being established that deals with corona cases in Dwer region in the Damascus countryside. What about more than two hundred thousand displaced people in the northern countryside of Aleppo (Al-Shahba)? Through the report, we see great efforts to help the Syrians ward off the threat of this epidemic, but it is very clear that they forgot a very large geographical spot in which thousands of displaced people are present, and whose presence has reached two years, amid great disregard from the World Health Organization and the Syrian government as well. -

Local Elections: Is Syria Moving to Reassert Central Control?

RESEARCH PROJECT REPORT FEBRUARY 2019/03 RESEARCH PROJECT LOCAL REPORT ELECTIONS: IS JUNE 2016 SYRIA MOVING TO REASSERT CENTRAL CONTROL? AUTHORS: AGNÈS FAVIER AND MARIE KOSTRZ © European University Institute,2019 Content© Agnès Favier and Marie Kostrz, 2019 This text may be downloaded only for personal research purposes. Additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copies or electronically, requires the consent of the authors. If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the year and the publisher. Requests should be addressed to [email protected]. Views expressed in this publication reflect the opinion of individual authors and not those of the European University Institute. Middle East Directions, Wartime and Post-Conflict in Syria Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies Research Project Report RSCAS/Middle East Directions 2019/03 February 2019 European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) www.eui.eu/RSCAS/Publications/ cadmus.eui.eu Local elections: Is Syria Moving to Reassert Central Control? Agnès Favier and Marie Kostrz1 1 Agnès Favier is a Research Fellow at the Middle East Directions Programme of the Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies. She leads the Syria Initiative and is Project Director of the Wartime and Post-Conflict in Syria (WPCS) project. Marie Kostrz is a research assistant for the Wartime and Post-Conflict in Syria (WPCS) project at the Middle East Directions Programme. This paper is the result of collective research led by the WPCS team. 1 Executive summary Analysis of the local elections held in Syria on the 16th of September 2018 reveals a significant gap between the high level of regime mobilization to bring them about and the low level of civilian expectations regarding their process and results. -

Highlights Situation Overview

Syria Crisis Bi-Weekly Situation Report No. 05 (as of 22 May 2016) This report is produced by the OCHA Syria Crisis offices in Syria, Turkey and Jordan. It covers the period from 7-22 May 2016. The next report will be issued in the second week of June. Highlights Rising prices of fuel and basic food items impacting upon health and nutritional status of Syrians in several governorates Children and youth continue to suffer disproportionately on frontlines Five inter-agency convoys reach over 50,000 people in hard-to-reach and besieged areas of Damascus, Rural Damascus and Homs Seven cross-border consignments delivered from Turkey with aid for 631,150 people in northern Syria Millions of people continued to be reached from inside Syria through the regular programme Heightened fighting displaces thousands in Ar- Raqqa and Ghouta Resumed airstrikes on Dar’a prompting displacement 13.5 M 13.5 M 6.5 M 4.8 M People in Need Targeted for assistance Internally displaced Refugees in neighbouring countries Situation Overview The reporting period was characterised by evolving security and conflict dynamics which have had largely negative implications for the protection of civilian populations and humanitarian access within locations across the country. Despite reaffirmation of a commitment to the country-wide cessation of hostilities agreement in Aleppo, and a brief reduction in fighting witnessed in Aleppo city, civilians continued to be exposed to both indiscriminate attacks and deprivation as parties to the conflict blocked access routes to Aleppo city and between cities and residential areas throughout northern governorates. Consequently, prices for fuel, essential food items and water surged in several locations as supply was threatened and production became non-viable, with implications for both food and water security of affected populations. -

Jun 2 3 2010 Libraries

Developing Heritage: Activist Decision-Makers and Reproduced Narratives in the Old City of Aleppo, Syria By Bernadette Baird-Zars B.A. Political Science and Education Swarthmore College, 2006 Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of ARCHNES MASTER IN CITY PLANNING MASSACHUSES INSTft1JTE OF TECHNOLOGY at the JUN 2 3 2010 MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY LIBRARIES June 2010 C 2010 Bernadette Baird-Zars. All Rights Reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT the permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of the thesis document in whole or in part. Author Department of Urban Studies aknd vAiing ) May 20, 2010 Certified by Professor Annette Kim Department of Urban Studies and Planning Thesis Supervisor Accepted by_ Professor Joseph Ferreira Chair, MCP Committee Department of Urban Studies and Planning Developing Heritage: Activist Decision-Makers and Reproduced Narratives in the Old City of Aleppo, Syria By Bernadette Baird-Zars Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning on May 20, 2010 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master in City Planning at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology ABSTRACT Aleppo's rehabilitation project has received plaudits for its comprehensive pro-resident approach and an active stance to limit gentrification and touristification. As this objective goes against many of the structural and economic interests in the city, the 'illogical' aspects of plans and regulations would be expected to be immediately transgressed. Surprisingly, however, municipal regulation of investments for significant new uses of property is strong, as is the provision of services to neighborhoods with little to no expected returns. -

Syria, a Country Study

Syria, a country study Federal Research Division Syria, a country study Table of Contents Syria, a country study...............................................................................................................................................1 Federal Research Division.............................................................................................................................2 Foreword........................................................................................................................................................5 Preface............................................................................................................................................................6 GEOGRAPHY...............................................................................................................................................7 TRANSPORTATION AND COMMUNICATIONS....................................................................................8 NATIONAL SECURITY..............................................................................................................................9 MUSLIM EMPIRES....................................................................................................................................10 Succeeding Caliphates and Kingdoms.........................................................................................................11 Syria.............................................................................................................................................................12 -

On the Lived Experience of the Syrian Diaspora in Canada

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2019-01-03 On the Lived Experience of the Syrian Diaspora in Canada Alatrash, Ghada Alatrash, G. (2019). On the Lived Experience of the Syrian Diaspora in Canada (Unpublished doctoral thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/109417 doctoral thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY On the Lived Experience of the Syrian Diaspora in Canada by Ghada Alatrash A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN EDUCATIONAL RESEARCH CALGARY, ALBERTA JANUARY, 2019 © Ghada Alatrash 2019 Abstract The Syrian Diaspora today is a complex topic that speaks to issues of dislocation, displacement, loss, exile, identity, resilience and a desire for belonging. My research sought to better understand these issues and the lived experience and human condition of the Syrian Diaspora. In my research, I thought through this main question: How do Syrian newcomers come to make sense of what it means to have lost a home and a homeland as it relates to the Syrian Diasporic experience? I broached the Syrian diasporic subject by thinking through an anti-Orientalist, anti- colonial framework, and I engaged autoethnography as a research methodology and as a method as I reflexively thought through and wrote from my own personal experience as a Syrian immigrant so that I could better understand the Syrian refugee’s human experience. -

Download S/2013/735

United Nations A/68/663–S/2013/735 General Assembly Distr.: General 13 December 2013 Security Council Original: English General Assembly Security Council Sixty-eighth session Sixty-eighth year Agenda item 33 Prevention of armed conflict Identical letters dated 13 December 2013 from the Secretary-General addressed to the President of the General Assembly and the President of the Security Council I have the honour to convey herewith the final report of the United Nations Mission to Investigate Allegations of the Use of Chemical Weapons in the Syrian Arab Republic (see annex). I would be grateful if the present final report, the letter of transmittal and its appendices could be brought to the attention of the Members of the General Assembly and of the Security Council. (Signed) BAN Ki-moon 13-61784 (E) 131213 *1361784* A/68/663 S/2013/735 Annex Letter of transmittal Having completed our investigation into the allegations of the use of chemical weapons in the Syrian Arab Republic reported to you by Member States, and further to the report of the United Nations Mission to Investigate Allegations of the Use of Chemical Weapons in the Syrian Arab Republic (hereinafter, the “United Nations Mission”) on allegations of the use of the chemical weapons in the Ghouta area of Damascus on 21 August 2013 (A/67/997-S/2013/553), we have the honour to submit the final report of the United Nations Mission. To date, 16 allegations of separate incidents involving the use of chemical weapons have been reported to the Secretary-General by Member States, including, primarily, the Governments of France, Qatar, the Syrian Arab Republic, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and the United States of America. -

International Swiss Architect Pierre De Meuron Visit Day

Draft proposal – International Swiss Architect Pierre De Meuron visit Day one: Wednesday Sep 29 / arrival – Damascus ‐ Receiving (and issuing visas) at Damascus airport ‐ Checking in the hotel ( I recommend the Art House or the Four Seasons). ‐ Short rest ‐ Meeting at the hotel ‐ Short car tour in the city ‐ Dinner at mount Qasyoun Day two: Thursday Sep 30 / Damascus ‐ National museum and Taqiyya Sulaimaniyya ‐ Old city ‐ Dinner at Narenj Rest. In the old city Day three Friday Oct 1 / Bosra and southern region ‐ From Damascus to Bosra (through Shahba and Qanawat) ‐ Bosra tour including lunch ‐ Brom Bosra back to Damascus (through Daraa) ‐ Dinner at Art House in Damascus Day four: Saturday Oct 2 / Palmyra (accompanied by professional designated guide) ‐ From Damascus to Palmyra ‐ Palmyra tour ‐ Dinner and stay in Palmyra (recommended at AL‐Cham hotel) Day five: Sunday Oct 3 / middle region ‐ From Palmyra to Hamah through Homs (visit Hamah museum) ‐ From Hamah to Aleppo (through Ebla) ‐ Dinner and stay in Aleppo (recommended at Al Mansouri in the old city or in the Sheraton) Day six: Monday Oct 4 / Aleppo – north region ‐ Old city and citadel of Aleppo ‐ St. Simon (and parts of the dead cities) ‐ Back to Aleppo Day seven: Tuesday Oct 5 ‐ Back to Damascus (via plane) ‐ Free day in Damascus region (available for the intended potential meeting) Day eight: Wednesday Oct 6 ‐ Available for the meeting ‐ Departure Note: an alternative way from Homs to Aleppo is not to go directly north through Hamah but to go north west through the coastal region visiting some important medieval castles, and Phoenician sites as well as spectacular scenery, all the way to Lattakia through Tartous and then from Lattakia to Aleppo through Hellenistic Aphamea and classical (Byzantine) dead cites. -

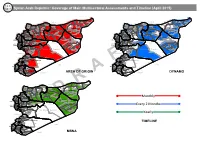

Monthly Every 2 Months Yearly

Syrian Arab Republic: Coverage of Main Multisectoral Assessments and Timeline (April 2015) Al-Malikeyyeh Al-Malikeyyeh Turkey Turkey Quamishli Quamishli Jarablus Jarablus Ras Al Ain Ras Al Ain Afrin Ain Al Arab Afrin Ain Al Arab Azaz Tell Abiad Azaz Tell Abiad Al-Hasakeh Al Bab Al-Hasakeh Al Bab Al-Hasakeh Al-Hasakeh Harim Harim Jebel Saman Ar-Raqqa Jebel Saman Ar-Raqqa Menbij Menbij Aleppo Aleppo Ar-Raqqa Idleb Ar-Raqqa Idleb Jisr-Ash-Shugur Jisr-Ash-Shugur As-Safira Ariha As-Safira Lattakia Ariha Ath-Thawrah Lattakia Ath-Thawrah Al-Haffa Idleb Al-Haffa Idleb Deir-ez-Zor Al Mara Deir-ez-Zor Al-Qardaha Al Mara Al-Qardaha As-Suqaylabiyah Deir-ez-Zor Lattakia As-Suqaylabiyah Deir-ez-Zor Lattakia Jablah Jablah Muhradah Muhradah As-Salamiyeh As-Salamiyeh Hama Hama Banyas Banyas Hama Sheikh Badr Masyaf Hama Sheikh Badr Masyaf Tartous Tartous Dreikish Al Mayadin Dreikish Ar-Rastan Al Mayadin Ar-Rastan Tartous TartousSafita Al Makhrim Safita Al Makhrim Tall Kalakh Tall Kalakh Homs Syrian Arab Republic Homs Syrian Arab Republic Al-Qusayr Al-Qusayr Abu Kamal Abu Kamal Tadmor Tadmor Homs Homs Lebanon Lebanon An Nabk An Nabk Yabroud Yabroud Al Qutayfah Al Qutayfah Az-Zabdani Az-Zabdani At Tall At Tall Rural Damascus Rural Damascus Rural Damascus Rural Damascus Damascus Damascus Darayya Darayya Duma Duma Qatana Qatana Rural Damascus Rural Damascus IraqIraq IraqIraq Quneitra As-Sanamayn Quneitra As-Sanamayn Dar'a Quneitra Dar'a Quneitra Shahba Shahba Al Fiq Izra Al Fiq Izra As-Sweida As-Sweida As-Sweida As-Sweida Dara Jordan AREA OF ORIGIN Dara Jordan -

FABRICATING FIDELITY: NATION-BUILDING, INTERNATIONAL LAW, and the GREEK-TURKISH POPULATION EXCHANGE by Umut Özsu a Thesis

FABRICATING FIDELITY: NATION-BUILDING, INTERNATIONAL LAW, AND THE GREEK-TURKISH POPULATION EXCHANGE by Umut Özsu A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Juridical Sciences Faculty of Law University of Toronto © Copyright by Umut Özsu (2011) Abstract FABRICATING FIDELITY: NATION-BUILDING, INTERNATIONAL LAW, AND THE GREEK-TURKISH POPULATION EXCHANGE Umut Özsu Doctor of Juridical Sciences (S.J.D.) Faculty of Law University of Toronto 2011 This dissertation concerns a crucial episode in the international legal history of nation-building: the Greek-Turkish population exchange. Supported by Athens and Ankara, and implemented largely by the League of Nations, the population exchange showcased the new pragmatism of the post-1919 order, an increased willingness to adapt legal doctrine to local conditions. It also exemplified a new mode of non-military nation-building, one initially designed for sovereign but politico-economically weak states on the semi-periphery of the international legal order. The chief aim here, I argue, was not to organize plebiscites, channel self-determination claims, or install protective mechanisms for vulnerable minorities Ŕ all familiar features of the Allied Powers‟ management of imperial disintegration in central and eastern Europe after the First World War. Nor was the objective to restructure a given economy and society from top to bottom, generating an entirely new legal order in the process; this had often been the case with colonialism in Asia and Africa, and would characterize much of the mandates system ii throughout the interwar years. Instead, the goal was to deploy a unique mechanism Ŕ not entirely in conformity with European practice, but also distinct from non-European governance regimes Ŕ to reshape the demographic composition of Greece and Turkey. -

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk 1 Mustafa Kemal Atatürk

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk 1 Mustafa Kemal Atatürk Mustafa Kemal Atatürk [[file:MustafaKemalAtaturk.jpg alt=]] President Atatürk 1st President of Turkey In office 29 October 1923 – 10 November 1938 (15 years, 12 days) Prime Minister Ali Fethi Okyar İsmet İnönü Celâl Bayar Succeeded by İsmet İnönü 1st Prime Minister of Turkey In office 3 May 1920 – 24 January 1921 (0 years, 266 days) Succeeded by Fevzi Çakmak 1st Speaker of the Parliament of Turkey In office 24 April 1920 – 29 October 1923 (3 years, 219 days) Succeeded by Ali Fethi Okyar 1st Leader of the Republican People's Party In office 9 September 1923 – 10 November 1938 (15 years, 62 days) Succeeded by İsmet İnönü Personal details Born 19 May 1881 (Conventional. This date was adopted by the president himself for official purposes in the absence of precise knowledge concerning the real date.)Salonica, Ottoman Empire (present-day Thessaloniki, Greece) Died 10 November 1938 (aged 57)Dolmabahçe Palace Istanbul, Turkey Resting place Anıtkabir Ankara, Turkey Nationality Turkish Political party Committee of Union and Progress, Republican People's Party Spouse(s) Lâtife Uşaklıgil (1923–25) Religion See Mustafa Kemal Atatürk's religious views. Signature Military service Mustafa Kemal Atatürk 2 Allegiance Ottoman Empire (1893 – 8 July 1919) Republic of Turkey (9 July 1919 – 30 June 1927) Army Service/branch Rank Ottoman Empire: General (Pasha) Republic of Turkey: Mareşal (Marshal) Commands 19th Division – 16th Corps – 2nd Army – 7th Army – Yildirim Army Group – commander-in-chief of Army of the -

U.S. Benefits from Terrorist Efforts Disrupting Syria: Russia

Syrian President Designates Arnous to Form New Gov’t Thought for Today DAMASCUS (Dispatches) – Syrian President Bashar al- Assad designated Hussein Arnous to form a new government, If two opposite theories are propagated one the Syrian presidency said on Tuesday, following a parliamen- tary election in July. will be wrong. Hussein Arnous was prime minister in the outgoing govern- ment, appointed by President Assad in June to replace Imad Khamis. Amir al-Momeneen Ali (AS) VOL NO: LV 11238 TEHRAN / Est.1959 Wednesday, August 26, 2020, Shahrivar 5, 1399, Muharram 6, 1442 Palestine: U.S. Trying to U.S. Benefits From Terrorist Break Apart Region Efforts Disrupting Syria: Russia of the Euphrates. promised that the operation Pointing to a recent uptick in would continue until the com- terrorist activity in the Syrian plete destruction of all U.S.- Desert area, the spokesman said controlled armed groups in the it could be attributed to an ‘am- area. nesty’ program for former mili- The comments by the spokes- tants by Washington’s Kurdish man came as Russia reported allies. on Tuesday that a joint Russia- The spokesman also pointed to Turkey patrol came under fire efforts by the militants to com- in Idlib, Syria. The incident mit acts of sabotage. Earlier this resulted in an armored vehicle month, a Russian major general being damaged and two Rus- Palestinians take part in a protest against the United Arab Emirates’ deal with was killed after an improvised sian servicemen being slightly the Zionist regime to normalize relations, in Gaza City August 19, 2020. explosive device (IED) laid by injured.