From Daraa to Damascus: Regional and Temporal Protest Variation in Syria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Revolutions in the Arab World Political, Social and Humanitarian Aspects

REPORT PREPARED WITHIN FRAMEWORK OF THE PROJECT EXPANSION OF THE LIBRARY OF COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION UNIT, CO-FUNDED BY EUROPEAN REFUGEE FUND REVOLUTIONS IN THE ARAB WORLD POLITICAL, SOCIAL AND HUMANITARIAN ASPECTS RADOSŁAW BANIA, MARTA WOŹNIAK, KRZYSZTOF ZDULSKI OCTOBER 2011 COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION UNIT OFFICE FOR FOREIGNERS, POLAND DECEMBER 2011 EUROPEJSKI FUNDUSZ NA RZECZ UCHODŹCÓW REPORT PREPARED WITHIN FRAMEWORK OF THE PROJECT EXPANSION OF THE LIBRARY OF COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION UNIT, CO-FUNDED BY EUROPEAN REFUGEE FUND REVOLUTIONS IN THE ARAB WORLD POLITICAL, SOCIAL AND HUMANITARIAN ASPECTS RADOSŁAW BANIA, MARTA WOŹNIAK, KRZYSZTOF ZDULSKI COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION UNIT OFFICE FOR FOREIGNERS, POLAND OCTOBER 2011 EUROPEAN REFUGEE FUND Revolutions in the Arab World – Political, Social and Humanitarian Aspects Country of Origin Information Unit, Office for Foreigners, 2011 Disclaimer The report at hand is a public document. It has been prepared within the framework of the project “Expansion of the library of Country of Origin Information Unit” no 1/7/2009/EFU, co- funded by the European Refugee Fund. Within the framework of the above mentioned project, COI Unit of the Office for Foreigners commissions reports made by external experts, which present detailed analysis of problems/subjects encountered during refugee/asylum procedures. Information included in these reports originates mainly from publicly available sources, such as monographs published by international, national or non-governmental organizations, press articles and/or different types of Internet materials. In some cases information is based also on experts’ research fieldworks. All the information provided in the report has been researched and evaluated with utmost care. -

Syria: Past, Present and Preservation

Syria: Past, Present and Preservation Emma Cunliffe, Durham University, and the Global Heritage Fund August 2011 1 The pleasure of food and drink lasts an hour, of sleep a day, of women a month, but of a building a lifetime ~ Arabic Proverb ~ (Unless otherwise stated, photographs are by The Fragile Crescent Project, Durham University, or Emma Cunliffe) 2 Carchemish Click here to explore Carchemish (Syria / Turkey) in the Global Heritage Network Threat Level: At Risk Carchemish was an important Mitanni, Hittite and Neo-Assyrian city on the edge of the Euphrates. Partially excavated by Leonard Woolley in the early twentieth century, it now lies in the no-man’s land between Syria and Turkey. Approximately 40% of the lower town lies in the Syrian side of the border, whilst the main tell, and rest of the lower town are in Turkey. The Turkish side has a military border outpost on the top of the citadel, and large parts of it were mined, but mine-removal was completed in 2010, paving the way for an era of accessibility. Excavations are intended to start there soon, and plans are currently being drawn up to turn it into a large archaeological park to boost tourism in the area. The lower town on the Syrian side has been damaged by the expansion of the nearby town of Jerablus. Since the 1960s the town has expanded inside the old city walls, destroying the ancient settlement. A few features remain, however, and are still visible today. Those parts of the lower town not under the modern urban fabric are now part of a heavily irrigated intensively farmed agricultural area which is composed of fields and orchards, and the city walls are being bulldozed to extend the fields. -

108 Kansas History “Facing This Vast Hardness”: the Plains Landscape and the People Shaped by It in Recent Kansas/Plains Film

Premiere of Dark Command, Lawrence, 1940. Courtesy of the Douglas County Historical Society, Watkins Museum of History, Lawrence, Kansas. Kansas History: A Journal of the Central Plains 38 (Summer 2015): 108–135 108 Kansas History “Facing This Vast Hardness”: The Plains Landscape and the People Shaped by It in Recent Kansas/Plains Film edited and introduced by Thomas Prasch ut the great fact was the land itself which seemed to overwhelm the little beginnings of human society that struggled in its sombre wastes. It was from facing this vast hardness that the boy’s mouth had become so “ bitter; because he felt that men were too weak to make any mark here, that the land wanted to be let alone, to preserve its own fierce strength, its peculiar, savage kind of beauty, its uninterrupted mournfulness” (Willa Cather, O Pioneers! [1913], p. 15): so the young boy Emil, looking out at twilight from the wagon that bears him backB to his homestead, sees the prairie landscape with which his family, like all the pioneers scattered in its vastness, must grapple. And in that contest between humanity and land, the land often triumphed, driving would-be settlers off, or into madness. Indeed, madness haunts the pages of Cather’s tale, from the quirks of “Crazy Ivar” to the insanity that leads Frank Shabata down the road to murder and prison. “Prairie madness”: the idea haunts the literature and memoirs of the early Great Plains settlers, returns with a vengeance during the Dust Bowl 1930s, and surfaces with striking regularity even in recent writing of and about the plains. -

"Infidelity" As an "Act of Love": Patrick Marber's After Miss Julie (1995) As a Rewrite of August Strindberg's Miss Julie (1888)

"Infidelity" as an "Act of Love": Patrick Marber's After Miss Julie (1995) as a Rewrite of August Strindberg's Miss Julie (1888). مسـرحيــة After Miss Julie للكاتب البريطاني باتريك ماربر كإعادة إبداع لمسرحية Miss Julie للكاتب السويدي أوجست ستريندبرج Dr. Reda Shehata associate professor Department of English - Zagazig University د. رضا شحاته أستاذ مساعد بقسم اللغة اﻹنجليزية كلية اﻵداب - جامعة الزقازيق "Infidelity" as an "Act of Love" Patrick Marber's After Miss Julie (1995) "Infidelity" as an "Act of Love": Patrick Marber's After Miss Julie (1995) as a Rewrite of August Strindberg's Miss Julie (1888). Abstract Depending on Linda Hutcheon's notion of adaptation as "a creative and interpretative act of appropriation" and David Lane's concept of the updated "context of the story world in which the characters are placed," this paper undertakes a critical examination of Patrick Marber's After Miss Julie (1995) as a creative rewrite of August Strindberg's Miss Julie (1888). The play appears to be both a faithful adaptation and appropriation of its model, reflecting "matches" for certain features of it and "mismatches" for others. So in spite of Marber's different language, his adjustment of the "temporal and spatial dimensions" of the original, and his several additions and omissions, he retains the same theme, characters, and—to a considerable extent, plot. To some extent, he manages to stick to his master's brand of Naturalism by retaining the special form of conflict upon which the action is based. In addition to its depiction of the failure of post-war class system, it shows strong relevancy to the spirit of the 1990s, both in its implicit critique of some aspects of feminism (especially its call for gender equality) and its bold address of the masculine concerns of that period. -

Report of the Secretary-General

United Nations S/2017/623 Security Council Distr.: General 21 July 2017 Original: English Implementation of Security Council resolutions 2139 (2014), 2165 (2014), 2191 (2014), 2258 (2015) and 2332 (2016) Report of the Secretary-General I. Introduction 1. The present report is the forty-first submitted pursuant to paragraph 17 of Security Council resolution 2139 (2014), paragraph 10 of resolution 2165 (2014), paragraph 5 of resolution 2191 (2014), paragraph 5 of resolution 2258 (2015) and paragraph 5 of resolution 2332 (2016), in which the Council requested the Secretary-General to report, every 30 days, on the implementation of the resolutions by all parties to the conflict in the Syrian Arab Republic. 2. The information contained herein is based on the data available to United Nations agencies, from the Government of the Syrian Arab Republic and from other Syrian and open sources. Data from United Nations agencies on their humanitarian deliveries have been reported for the period from 1 to 30 June 2017. Box 1 Key points in June 2017 (1) The memorandum on the creation of de-escalation areas in the Syrian Arab Republic, signed by Iran (Islamic Republic of), the Russian Federation and Turkey on 4 May, continued to show a positive trend of reducing violence; however, hostilities have continued to be reported, especially in Dar‘a and eastern Ghutah, and in areas held by Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL). (2) Only three inter-agency cross-line convoys were dispatched in June. Of these, only one, a convoy to east Harasta, Misraba and Mudayra on 19 June, reached a besieged area. -

“No One's Left” Summary Executions by Syrian Forces in Al-Bayda

HUMAN RIGHTS “No One’s Left” Summary Executions by Syrian Forces in al-Bayda & Baniyas WATCH “No One’s Left” Summary Executions by Syrian Forces in al-Bayda and Baniyas Copyright © 2013 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. ISBN: 978-1-62313-0480 Printed in the United States of America Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. We investigate and expose human rights violations and hold abusers accountable. We challenge governments and those who hold power to end abusive practices and respect international human rights law. We enlist the public and the international community to support the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org SEPTEMBER 2013 978-1-62313-0480 “No One’s Left” Summary Executions by Syrian Forces in al-Bayda and Baniyas Maps ................................................................................................................................... i Summary .......................................................................................................................... -

Situation Report: WHO Syria, Week 19-20, 2019

WHO Syria: SITUATION REPORT Weeks 32 – 33 (2 – 15 August), 2019 I. General Development, Political and Security Situation (22 June - 4 July), 2019 The security situation in the country remains volatile and unstable. The main hot spots remain Daraa, Al- Hassakah, Deir Ezzor, Latakia, Hama, Aleppo and Idlib governorates. The security situation in Idlib and North rural Hama witnessed a notable escalation in the military activities between SAA and NSAGs, with SAA advancement in the area. Syrian government forces, supported by fighters from allied popular defense groups, have taken control of a number of villages in the southern countryside of the northwestern province of Idlib, reaching the outskirts of a major stronghold of foreign-sponsored Takfiri militants there The Southern area, particularly in Daraa Governorate, experienced multiple attacks targeting SAA soldiers . The security situation in the Central area remains tense and affected by the ongoing armed conflict in North rural Hama. The exchange of shelling between SAA and NSAGs witnessed a notable increase resulting in a high number of casualties among civilians. The threat of ERWs, UXOs and Landmines is still of concern in the central area. Two children were killed, and three others were seriously injured as a result of a landmine explosion in Hawsh Haju town of North rural Homs. The general situation in the coastal area is likely to remain calm. However, SAA military operations are expected to continue in North rural Latakia and asymmetric attacks in the form of IEDs, PBIEDs, and VBIEDs cannot be ruled out. II. Key Health Issues Response to Al Hol camp: The Security situation is still considered as unstable inside the camp due to the stress caused by the deplorable and unbearable living conditions the inhabitants of the camp have been experiencing . -

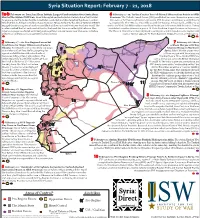

Syria SITREP Map 07

Syria Situation Report: February 7 - 21, 2018 1a-b February 10: Israel and Iran Initiate Largest Confrontation Over Syria Since 6 February 9 - 15: Turkey Creates Two Additional Observation Points in Idlib Start of the Syrian Civil War: Israel intercepted and destroyed an Iranian drone that violated Province: The Turkish Armed Forces (TSK) established two new observation points near its airspace over the Golan Heights. Israel later conducted airstrikes targeting the drone’s control the towns of Tal Tuqan and Surman in Eastern Idlib Province on February 9 and February vehicle at the T4 Airbase in Eastern Homs Province. Syrian Surface-to-Air Missile Systems (SAMS) 15, respectively. The TSK also reportedly scouted the Taftanaz Airbase north of Idlib City as engaged the returning aircraft and successfully shot down an Israeli F-16 over Northern Israel. The well as the Wadi Deif Military Base near Khan Sheikhoun in Southern Idlib Province. Turkey incident marked the first such combat loss for the Israeli Air Force since the 1982 Lebanon War. established a similar observation post at Al-Eis in Southern Aleppo Province on February 5. Israel in response conducted airstrikes targeting at least a dozen targets near Damascus including The Russian Armed Forces later deployed a contingent of military police to the regime-held at least four military positions operated by Iran in Syria. town of Hadher opposite Al-Eis in Southern Aleppo Province on February 14. 2 February 17 - 20: Pro-Regime Forces Set Qamishli 7 February 18: Ahrar Conditions for Major Offensive in Eastern a-Sham Merges with Key Ghouta: Pro-regime forces intensified a campaign 9 Islamist Group in Northern of airstrikes and artillery shelling targeting the 8 Syria: Salafi-Jihadist group Ahrar opposition-held Eastern Ghouta suburbs of Al-Hasakah a-Sham merged with Islamist group Damascus, killing at least 250 civilians. -

REGIONAL ANALYSIS SYRIA Received Little Or No Humanitarian Assistance in More Than 10 Months

currently estimated to be living in hard to reach or besieged areas, having REGIONAL ANALYSIS SYRIA received little or no humanitarian assistance in more than 10 months. 07 February 2014 Humanitarian conditions in Yarmouk camp continued to worsen with 70 reported deaths in the last 4 months due to the shortage of food and medical supplies. Local negotiations succeeded in facilitating limited amounts of humanitarian Part I – Syria assistance to besieged areas, including Yarmouk, Modamiyet Elsham and Content Part I Barzeh neighbourhoods in Damascus although the aid provided was deeply This Regional Analysis of the Syria conflict (RAS) is an update of the December RAS and seeks to Overview inadequate. How to use the RAS? bring together information from all sources in the The spread of polio remains a major concern. Since first confirmed in October region and provide holistic analysis of the overall Possible developments Syria crisis. In addition, this report highlights the Map - Latest developments 2013, a total of 93 polio cases have been reported; the most recent case in Al key humanitarian developments in 2013. While Key events 2013 Hasakeh in January. In January 2014 1.2 million children across Aleppo, Al Part I focuses on the situation within Syria, Part II Information gaps and data limitations Hasakeh, Ar-Raqqa, Deir-ez-Zor, Hama, Idleb and Lattakia were vaccinated covers the impact of the crisis on neighbouring Operational constraints achieving an estimated 88% coverage. The overall health situation is one of the countries. More information on how to use this Humanitarian profile document can be found on page 2. -

Bashar Al-Assad's Struggle for Survival

Bashar al-Assad’s Struggle for Survival: Has the Miracle Occurred? Eyal Zisser The summer of 2014 marked the beginning of a turn in the tide of the civil war in Syria. The accomplishments of the rebels in battles against the regime tilted the scales in their favor and raised doubts regarding Bashar al-Assad’s ability to continue securing his rule, even in the heart of the Syrian state – the thin strip stretching from the capital Damascus to the city of Aleppo, to the Alawite coastal region in the north, and perhaps also to the city of Daraa and the Druze Mountain in the south. This changing tide in the Syrian war was the result of the ongoing depletion of the ranks of the Syrian regime and the exhaustion of the manpower at its disposal. Marked by fatigue and low morale, Bashar’s army was in growing need of members of his Alawite community who remained willing to fight and even die for him, as well as the Hizbollah fighters who were sent to his aid from neighboring Lebanon. The rebels, on the other hand, proved motivated, determined, and capable of perseverance. Indeed, they succeeded in unifying their ranks, and today, in contrast to the hundreds of groups that had been operating throughout the country, there are now only a few groups operating – all, incidentally, of radical Islamic character. Countries coming to the aid of the rebels also included Turkey, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia, who decided to topple the Assad regime and showed determination equal to that of Bashar’s allies – Iran, Hizbollah, and Russia. -

The Political Analysis of the Syrian Crisis and the Zero-Problem Policy with Syria

THE POLITICAL ANALYSIS OF THE SYRIAN CRISIS AND THE ZERO-PROBLEM POLICY WITH SYRIA A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY ŞENOL ARSLANTAŞ IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN THE DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS DECEMBER 2013 Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences Prof.Dr. Meliha B. ALTUNIŞIK Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Master of Science. Prof. Dr. Hüseyin BAĞCI Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Science. Prof. Dr. Süha BÖLÜKBAŞIOĞLU Supervisor Examining Committee Members Prof. Dr. İlhan UZGEL (ANKARA UNIV, IR) Prof. Dr. Süha BÖLÜKBAŞIOĞLU (METU, IR) Assoc. Prof. Dr. Özlem TÜR (METU, IR) I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last name: Şenol ARSLANTAŞ Signature : iii ABSTRACT THE POLITICAL ANALYSIS OF THE SYRIAN CRISES AND THE ZERO-PROBLEM POLICY WITH SYRIA Arslantaş, Şenol M.Sc., Department of International Relations Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Süha Bölükbaşıoğlu December 2013, 118 pages This thesis aims to analyze both the evolution of Turkish-Syrian relations during the period of the AKP governments and the emergence of the Syrian revolt in March 2010. -

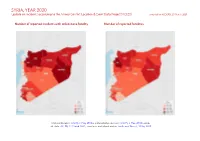

SYRIA, YEAR 2020: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 25 March 2021

SYRIA, YEAR 2020: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 25 March 2021 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, 6 May 2018a; administrative divisions: GADM, 6 May 2018b; incid- ent data: ACLED, 12 March 2021; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 SYRIA, YEAR 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 25 MARCH 2021 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Explosions / Remote Conflict incidents by category 2 6187 930 2751 violence Development of conflict incidents from 2017 to 2020 2 Battles 2465 1111 4206 Strategic developments 1517 2 2 Methodology 3 Violence against civilians 1389 760 997 Conflict incidents per province 4 Protests 449 2 4 Riots 55 4 15 Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 12062 2809 7975 Disclaimer 9 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 12 March 2021). Development of conflict incidents from 2017 to 2020 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 12 March 2021). 2 SYRIA, YEAR 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 25 MARCH 2021 Methodology GADM. Incidents that could not be located are ignored. The numbers included in this overview might therefore differ from the original ACLED data.