The Urban Development of Damascus: a Study of Its Past, Present and Future

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oral Update of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic

Distr.: General 18 March 2014 Original: English Human Rights Council Twenty-fifth session Agenda item 4 Human rights situations that require the Council’s attention Oral Update of the independent international commission of inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic 1 I. Introduction 1. The harrowing violence in the Syrian Arab Republic has entered its fourth year, with no signs of abating. The lives of over one hundred thousand people have been extinguished. Thousands have been the victims of torture. The indiscriminate and disproportionate shelling and aerial bombardment of civilian-inhabited areas has intensified in the last six months, as has the use of suicide and car bombs. Civilians in besieged areas have been reduced to scavenging. In this conflict’s most recent low, people, including young children, have starved to death. 2. Save for the efforts of humanitarian agencies operating inside Syria and along its borders, the international community has done little but bear witness to the plight of those caught in the maelstrom. Syrians feel abandoned and hopeless. The overwhelming imperative is for the parties, influential states and the international community to work to ensure the protection of civilians. In particular, as set out in Security Council resolution 2139, parties must lift the sieges and allow unimpeded and safe humanitarian access. 3. Compassion does not and should not suffice. A negotiated political solution, which the commission has consistently held to be the only solution to this conflict, must be pursued with renewed vigour both by the parties and by influential states. Among victims, the need for accountability is deeply-rooted in the desire for peace. -

Offensive Against the Syrian City of Manbij May Be the Beginning of a Campaign to Liberate the Area Near the Syrian-Turkish Border from ISIS

June 23, 2016 Offensive against the Syrian City of Manbij May Be the Beginning of a Campaign to Liberate the Area near the Syrian-Turkish Border from ISIS Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) fighters at the western entrance to the city of Manbij (Fars, June 18, 2016). Overview 1. On May 31, 2016, the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), a Kurdish-dominated military alliance supported by the United States, initiated a campaign to liberate the northern Syrian city of Manbij from ISIS. Manbij lies west of the Euphrates, about 35 kilometers (about 22 miles) south of the Syrian-Turkish border. In the three weeks since the offensive began, the SDF forces, which number several thousand, captured the rural regions around Manbij, encircled the city and invaded it. According to reports, on June 19, 2016, an SDF force entered Manbij and occupied one of the key squares at the western entrance to the city. 2. The declared objective of the ground offensive is to occupy Manbij. However, the objective of the entire campaign may be to liberate the cities of Manbij, Jarabulus, Al-Bab and Al-Rai, which lie to the west of the Euphrates and are ISIS strongholds near the Turkish border. For ISIS, the loss of the area is liable to be a severe blow to its logistic links between the outside world and the centers of its control in eastern Syria (Al-Raqqah), Iraq (Mosul). Moreover, the loss of the region will further 112-16 112-16 2 2 weaken ISIS's standing in northern Syria and strengthen the military-political position and image of the Kurdish forces leading the anti-ISIS ground offensive. -

Syria and Repealing Decision 2011/782/CFSP

30.11.2012 EN Official Journal of the European Union L 330/21 DECISIONS COUNCIL DECISION 2012/739/CFSP of 29 November 2012 concerning restrictive measures against Syria and repealing Decision 2011/782/CFSP THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION, internal repression or for the manufacture and maintenance of products which could be used for internal repression, to Syria by nationals of Member States or from the territories of Having regard to the Treaty on European Union, and in Member States or using their flag vessels or aircraft, shall be particular Article 29 thereof, prohibited, whether originating or not in their territories. Whereas: The Union shall take the necessary measures in order to determine the relevant items to be covered by this paragraph. (1) On 1 December 2011, the Council adopted Decision 2011/782/CFSP concerning restrictive measures against Syria ( 1 ). 3. It shall be prohibited to: (2) On the basis of a review of Decision 2011/782/CFSP, the (a) provide, directly or indirectly, technical assistance, brokering Council has concluded that the restrictive measures services or other services related to the items referred to in should be renewed until 1 March 2013. paragraphs 1 and 2 or related to the provision, manu facture, maintenance and use of such items, to any natural or legal person, entity or body in, or for use in, (3) Furthermore, it is necessary to update the list of persons Syria; and entities subject to restrictive measures as set out in Annex I to Decision 2011/782/CFSP. (b) provide, directly or indirectly, financing or financial assistance related to the items referred to in paragraphs 1 (4) For the sake of clarity, the measures imposed under and 2, including in particular grants, loans and export credit Decision 2011/273/CFSP should be integrated into a insurance, as well as insurance and reinsurance, for any sale, single legal instrument. -

The Potential for an Assad Statelet in Syria

THE POTENTIAL FOR AN ASSAD STATELET IN SYRIA Nicholas A. Heras THE POTENTIAL FOR AN ASSAD STATELET IN SYRIA Nicholas A. Heras policy focus 132 | december 2013 the washington institute for near east policy www.washingtoninstitute.org The opinions expressed in this Policy Focus are those of the author and not necessar- ily those of The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, its Board of Trustees, or its Board of Advisors. MAPS Fig. 1 based on map designed by W.D. Langeraar of Michael Moran & Associates that incorporates data from National Geographic, Esri, DeLorme, NAVTEQ, UNEP- WCMC, USGS, NASA, ESA, METI, NRCAN, GEBCO, NOAA, and iPC. Figs. 2, 3, and 4: detail from The Tourist Atlas of Syria, Syria Ministry of Tourism, Directorate of Tourist Relations, Damascus. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publica- tion may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. © 2013 by The Washington Institute for Near East Policy The Washington Institute for Near East Policy 1828 L Street NW, Suite 1050 Washington, DC 20036 Cover: Digitally rendered montage incorporating an interior photo of the tomb of Hafez al-Assad and a partial view of the wheel tapestry found in the Sheikh Daher Shrine—a 500-year-old Alawite place of worship situated in an ancient grove of wild oak; both are situated in al-Qurdaha, Syria. Photographs by Andrew Tabler/TWI; design and montage by 1000colors. -

Post-Reconciliation Rural Damascus: Are Local Communities Still Represented?

Post-Reconciliation Rural Damascus: Are Local Communities Still Represented? Mazen Ezzi Wartime and Post-Conflict in Syria (WPCS) Research Project Report 27 November 2020 2020/16 © European University Institute 2020 Content and individual chapters © Mazen Ezzi 2020 This work has been published by the European University Institute, Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies. This text may be downloaded only for personal research purposes. Additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copies or electronically, requires the consent of the authors. If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the year and the publisher. Requests should be addressed to [email protected]. Views expressed in this publication reflect the opinion of individual authors and not those of the European University Institute. Middle East Directions Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies Research Project Report RSCAS/Middle East Directions 2020/16 27 November 2020 European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) www.eui.eu/RSCAS/Publications/ cadmus.eui.eu Funded by the European Union Post-Reconciliation Rural Damascus: Are Local Communities Still Represented? Mazen Ezzi * Mazen Ezzi is a Syrian researcher working on the Wartime and Post-Conflict in Syria (WPCS) project within the Middle East Directions Programme hosted by the Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies at the European University Institute in Florence. Ezzi’s work focuses on the war economy in Syria and regime-controlled areas. This research report was first published in Arabic on 19 November 2020. It was translated into English by Alex Rowell. -

Revolutions in the Arab World Political, Social and Humanitarian Aspects

REPORT PREPARED WITHIN FRAMEWORK OF THE PROJECT EXPANSION OF THE LIBRARY OF COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION UNIT, CO-FUNDED BY EUROPEAN REFUGEE FUND REVOLUTIONS IN THE ARAB WORLD POLITICAL, SOCIAL AND HUMANITARIAN ASPECTS RADOSŁAW BANIA, MARTA WOŹNIAK, KRZYSZTOF ZDULSKI OCTOBER 2011 COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION UNIT OFFICE FOR FOREIGNERS, POLAND DECEMBER 2011 EUROPEJSKI FUNDUSZ NA RZECZ UCHODŹCÓW REPORT PREPARED WITHIN FRAMEWORK OF THE PROJECT EXPANSION OF THE LIBRARY OF COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION UNIT, CO-FUNDED BY EUROPEAN REFUGEE FUND REVOLUTIONS IN THE ARAB WORLD POLITICAL, SOCIAL AND HUMANITARIAN ASPECTS RADOSŁAW BANIA, MARTA WOŹNIAK, KRZYSZTOF ZDULSKI COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION UNIT OFFICE FOR FOREIGNERS, POLAND OCTOBER 2011 EUROPEAN REFUGEE FUND Revolutions in the Arab World – Political, Social and Humanitarian Aspects Country of Origin Information Unit, Office for Foreigners, 2011 Disclaimer The report at hand is a public document. It has been prepared within the framework of the project “Expansion of the library of Country of Origin Information Unit” no 1/7/2009/EFU, co- funded by the European Refugee Fund. Within the framework of the above mentioned project, COI Unit of the Office for Foreigners commissions reports made by external experts, which present detailed analysis of problems/subjects encountered during refugee/asylum procedures. Information included in these reports originates mainly from publicly available sources, such as monographs published by international, national or non-governmental organizations, press articles and/or different types of Internet materials. In some cases information is based also on experts’ research fieldworks. All the information provided in the report has been researched and evaluated with utmost care. -

BREAD and BAKERY DASHBOARD Northwest Syria Bread and Bakery Assistance 12 MARCH 2021

BREAD AND BAKERY DASHBOARD Northwest Syria Bread and Bakery Assistance 12 MARCH 2021 ISSUE #7 • PAGE 1 Reporting Period: DECEMBER 2020 Lower Shyookh Turkey Turkey Ain Al Arab Raju 92% 100% Jarablus Syrian Arab Sharan Republic Bulbul 100% Jarablus Lebanon Iraq 100% 100% Ghandorah Suran Jordan A'zaz 100% 53% 100% 55% Aghtrin Ar-Ra'ee Ma'btali 52% 100% Afrin A'zaz Mare' 100% of the Population Sheikh Menbij El-Hadid 37% 52% in NWS (including Tell 85% Tall Refaat A'rima Abiad district) don’t meet the Afrin 76% minimum daily need of bread Jandairis Abu Qalqal based on the 5Ws data. Nabul Al Bab Al Bab Ain al Arab Turkey Daret Azza Haritan Tadaf Tell Abiad 59% Harim 71% 100% Aleppo Rasm Haram 73% Qourqeena Dana AleppoEl-Imam Suluk Jebel Saman Kafr 50% Eastern Tell Abiad 100% Takharim Atareb 73% Kwaires Ain Al Ar-Raqqa Salqin 52% Dayr Hafir Menbij Maaret Arab Harim Tamsrin Sarin 100% Ar-Raqqa 71% 56% 25% Ein Issa Jebel Saman As-Safira Maskana 45% Armanaz Teftnaz Ar-Raqqa Zarbah Hadher Ar-Raqqa 73% Al-Khafsa Banan 0 7.5 15 30 Km Darkosh Bennsh Janudiyeh 57% 36% Idleb 100% % Bread Production vs Population # of Total Bread / Flour Sarmin As-Safira Minimum Needs of Bread Q4 2020* Beneficiaries Assisted Idleb including WFP Programmes 76% Jisr-Ash-Shugur Ariha Hajeb in December 2020 0 - 99 % Mhambal Saraqab 1 - 50,000 77% 61% Tall Ed-daman 50,001 - 100,000 Badama 72% Equal or More than 100% 100,001 - 200,000 Jisr-Ash-Shugur Idleb Ariha Abul Thohur Monthly Bread Production in MT More than 200,000 81% Khanaser Q4 2020 Ehsem Not reported to 4W’s 1 cm 3720 MT Subsidized Bread Al Ma'ra Data Source: FSL Cluster & iMMAP *The represented percentages in circles on the map refer to the availability of bread by calculating Unsubsidized Bread** Disclaimer: The Boundaries and names shown Ma'arrat 0.50 cm 1860 MT the gap between currently produced bread and bread needs of the population at sub-district level. -

Syria: Past, Present and Preservation

Syria: Past, Present and Preservation Emma Cunliffe, Durham University, and the Global Heritage Fund August 2011 1 The pleasure of food and drink lasts an hour, of sleep a day, of women a month, but of a building a lifetime ~ Arabic Proverb ~ (Unless otherwise stated, photographs are by The Fragile Crescent Project, Durham University, or Emma Cunliffe) 2 Carchemish Click here to explore Carchemish (Syria / Turkey) in the Global Heritage Network Threat Level: At Risk Carchemish was an important Mitanni, Hittite and Neo-Assyrian city on the edge of the Euphrates. Partially excavated by Leonard Woolley in the early twentieth century, it now lies in the no-man’s land between Syria and Turkey. Approximately 40% of the lower town lies in the Syrian side of the border, whilst the main tell, and rest of the lower town are in Turkey. The Turkish side has a military border outpost on the top of the citadel, and large parts of it were mined, but mine-removal was completed in 2010, paving the way for an era of accessibility. Excavations are intended to start there soon, and plans are currently being drawn up to turn it into a large archaeological park to boost tourism in the area. The lower town on the Syrian side has been damaged by the expansion of the nearby town of Jerablus. Since the 1960s the town has expanded inside the old city walls, destroying the ancient settlement. A few features remain, however, and are still visible today. Those parts of the lower town not under the modern urban fabric are now part of a heavily irrigated intensively farmed agricultural area which is composed of fields and orchards, and the city walls are being bulldozed to extend the fields. -

ASOR Cultural Heritage Initiatives (CHI): Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq1

ASOR Cultural Heritage Initiatives (CHI): Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq1 S-JO-100-18-CA-004 Weekly Report 209-212 — October 1–31, 2018 Michael D. Danti, Marina Gabriel, Susan Penacho, Darren Ashby, Kyra Kaercher, Gwendolyn Kristy Table of Contents: Other Key Points 2 Military and Political Context 3 Incident Reports: Syria 5 Heritage Timeline 72 1 This report is based on research conducted by the “Cultural Preservation Initiative: Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq.” Weekly reports reflect reporting from a variety of sources and may contain unverified material. As such, they should be treated as preliminary and subject to change. 1 Other Key Points ● Aleppo Governorate ○ Cleaning efforts have begun at the National Museum of Aleppo in Aleppo, Aleppo Governorate. ASOR CHI Heritage Response Report SHI 18-0130 ○ Illegal excavations were reported at Shash Hamdan, a Roman tomb in Manbij, Aleppo Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0124 ○ Illegal excavation continues at the archaeological site of Cyrrhus in Aleppo Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0090 UPDATE ● Deir ez-Zor Governorate ○ Artillery bombardment damaged al-Sayyidat Aisha Mosque in Hajin, Deir ez-Zor Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0118 ○ Artillery bombardment damaged al-Sultan Mosque in Hajin, Deir ez-Zor Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0119 ○ A US-led Coalition airstrike destroyed Ammar bin Yasser Mosque in Albu-Badran Neighborhood, al-Susah, Deir ez-Zor Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0121 ○ A US-led Coalition airstrike damaged al-Aziz Mosque in al-Susah, Deir ez-Zor Governorate. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Transnational Rebellion: The Syrian Revolt of 1925-1927 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/99q9f2k0 Author Bailony, Reem Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Transnational Rebellion: The Syrian Revolt of 1925-1927 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Reem Bailony 2015 © Copyright by Reem Bailony 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Transnational Rebellion: The Syrian Revolt of 1925-1927 by Reem Bailony Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Los Angeles, 2015 Professor James L. Gelvin, Chair This dissertation explores the transnational dimensions of the Syrian Revolt of 1925-1927. By including the activities of Syrian migrants in Egypt, Europe and the Americas, this study moves away from state-centric histories of the anti-French rebellion. Though they lived far away from the battlefields of Syria and Lebanon, migrants championed, contested, debated, and imagined the rebellion from all corners of the mahjar (or diaspora). Skeptics and supporters organized petition campaigns, solicited financial aid for rebels and civilians alike, and partook in various meetings and conferences abroad. Syrians abroad also clandestinely coordinated with rebel leaders for the transfer of weapons and funds, as well as offered strategic advice based on the political climates in Paris and Geneva. Moreover, key émigré figures played a significant role in defining the revolt, determining its goals, and formulating its program. By situating the revolt in the broader internationalism of the 1920s, this study brings to life the hitherto neglected role migrants played in bridging the local and global, the national and international. -

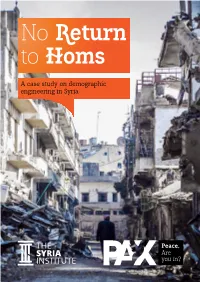

A Case Study on Demographic Engineering in Syria No Return to Homs a Case Study on Demographic Engineering in Syria

No Return to Homs A case study on demographic engineering in Syria No Return to Homs A case study on demographic engineering in Syria Colophon ISBN/EAN: 978-94-92487-09-4 NUR 689 PAX serial number: PAX/2017/01 Cover photo: Bab Hood, Homs, 21 December 2013 by Young Homsi Lens About PAX PAX works with committed citizens and partners to protect civilians against acts of war, to end armed violence, and to build just peace. PAX operates independently of political interests. www.paxforpeace.nl / P.O. Box 19318 / 3501 DH Utrecht, The Netherlands / [email protected] About TSI The Syria Institute (TSI) is an independent, non-profit, non-partisan research organization based in Washington, DC. TSI seeks to address the information and understanding gaps that to hinder effective policymaking and drive public reaction to the ongoing Syria crisis. We do this by producing timely, high quality, accessible, data-driven research, analysis, and policy options that empower decision-makers and advance the public’s understanding. To learn more visit www.syriainstitute.org or contact TSI at [email protected]. Executive Summary 8 Table of Contents Introduction 12 Methodology 13 Challenges 14 Homs 16 Country Context 16 Pre-War Homs 17 Protest & Violence 20 Displacement 24 Population Transfers 27 The Aftermath 30 The UN, Rehabilitation, and the Rights of the Displaced 32 Discussion 34 Legal and Bureaucratic Justifications 38 On Returning 39 International Law 47 Conclusion 48 Recommendations 49 Index of Maps & Graphics Map 1: Syria 17 Map 2: Homs city at the start of 2012 22 Map 3: Homs city depopulation patterns in mid-2012 25 Map 4: Stages of the siege of Homs city, 2012-2014 27 Map 5: Damage assessment showing targeted destruction of Homs city, 2014 31 Graphic 1: Key Events from 2011-2012 21 Graphic 2: Key Events from 2012-2014 26 This report was prepared by The Syria Institute with support from the PAX team. -

Human Rights Council Fact-Finding in S

Marauhn: Sailing Close to the Wind: Human Rights Council Fact-Finding in S SAILING CLOSE TO THE WIND: HUMAN RIGHTS COUNCIL FACT-FINDING IN SITUATIONS OF ARMED CONFLICT-THE CASE OF SYRIA THILO MARAUHN* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. FROM GRAFFITI IN DARA'A TO CIVIL WAR IN SYRIA ............ 402 II. SECURITY COUNCIL INACTION AND HUMAN RIGHTS ...... ..... 408 COUNCIL ACTIVISM ........................................... 408 A. Governments' Responses to the Situation in Syria ............. 409 B. Inaction of the U.N. Security Council .............. 415 C. Actions Taken by the U.N. General Assembly and the U.N. Human Rights Council ................. ....... 421 III. THE RISK OF BEING ALL-INCLUSIVE: BLURRING THE LINES.........426 A. Does the Situation in Syria Amount to a Non-International Armed Conflict? ...................... ..... 426 B. The Application ofHuman Rights Law in a Non-International Armed Conflict........................434 C. Fact-finding in Human Rights Law vs Fact-Finding with Respect to the Law ofArmed Conflict....... ............ 444 D. Does Blurringthe Lines Weaken Compliance with the Applicable Law? ................................448 IV. THE BENEFITS OF SAILING CLOSE TO THE WIND .................. 452 V. IMPROVING COMPLIANCE WITH THE LAW OF ARMED CONFLICT .............................................. 455 CONCLUSION ....................................... ....... 458 * M.Phil. (Wales), Dr. jur.utr. (Heidelberg), Professor of Public Law, International and European Law, Faculty of Law, Justus Liebig University, Giessen, Germany. The author is grateful to Charles H. B. Garraway, Colonel (ret.), United Kingdom; Nicolas Lang, Ambassador-at-Large for the Application of International Humanitarian Law, Switzerland; and Dr. Ignaz Stegmiller, Justus Liebig University, Germany for comments on earlier drafts. 401 Published by CWSL Scholarly Commons, 2013 1 California Western International Law Journal, Vol.