Evidence-Based Medicine: Is It a Bridge Too Far?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Explanatory to Pragmatic Clinical Trials: a New Era for Effectiveness Research

From Explanatory to Pragmatic Clinical Trials: A New Era for Effectiveness Research Jerry Jarvik, M.D., M.P.H. Professor of Radiology, Neurological Surgery and Health Services Adjunct Professor Orthopedic Surgery & Sports Medicine and Pharmacy Director, Comparative Effectiveness, Cost and Outcomes Research Center (CECORC) UTSW April 2018 Acknowledgements •NIH: UH2 AT007766; UH3 AT007766 •NIH P30AR072572 •PCORI: CE-12-11-4469 Disclosures Physiosonix (ultrasound company): Founder/stockholder UpToDate: Section Editor Evidence-Based Neuroimaging Diagnosis and Treatment (Springer): Co-Editor The Big Picture Comparative Effectiveness Evidence Based Practice Health Policy Learning Healthcare System So we need to generate evidence Challenge #1: Clinical research is slow • Tradi>onal RCTs are slow and expensive— and rarely produce findings that are easily put into prac>ce. • In fact, it takes an average of 17 ye ars before research findings Howlead pragmaticto widespread clinical trials canchanges improve in care. practice & policy Challenge #1: Clinical research is slow “…rarely produce findings that are easily put into prac>ce.” Efficacy vs. Effectiveness Efficacy vs. Effectiveness • Efficacy: can it work under ideal conditions • Effectiveness: does it work under real-world conditions Challenge #2: Clinical research is not relevant to practice • Tradi>onal RCTs study efficacy “If we want of txs for carefully selected more evidence- popula>ons under ideal based pr actice, condi>ons. we need more • Difficult to translate to real practice-based evidence.” world. Green, LW. American Journal • When implemented into of Public Health, 2006. How pragmatic clinical trials everyday clinical prac>ce, oZen seecan a “ voltage improve drop practice”— drama>c & decreasepolicy from efficacy to effec>veness. -

Cebm-Levels-Of-Evidence-Background-Document-2-1.Pdf

Background document Explanation of the 2011 Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (OCEBM) Levels of Evidence Introduction The OCEBM Levels of Evidence was designed so that in addition to traditional critical appraisal, it can be used as a heuristic that clinicians and patients can use to answer clinical questions quickly and without resorting to pre-appraised sources. Heuristics are essentially rules of thumb that helps us make a decision in real environments, and are often as accurate as a more complicated decision process. A distinguishing feature is that the Levels cover the entire range of clinical questions, in the order (from top row to bottom row) that the clinician requires. While most ranking schemes consider strength of evidence for therapeutic effects and harms, the OCEBM system allows clinicians and patients to appraise evidence for prevalence, accuracy of diagnostic tests, prognosis, therapeutic effects, rare harms, common harms, and usefulness of (early) screening. Pre-appraised sources such as the Trip Database (1), (2), or REHAB+ (3) are useful because people who have the time and expertise to conduct systematic reviews of all the evidence design them. At the same time, clinicians, patients, and others may wish to keep some of the power over critical appraisal in their own hands. History Evidence ranking schemes have been used, and criticised, for decades (4-7), and each scheme is geared to answer different questions(8). Early evidence hierarchies(5, 6, 9) were introduced primarily to help clinicians and other researchers appraise the quality of evidence for therapeutic effects, while more recent attempts to assign levels to evidence have been designed to help systematic reviewers(8), or guideline developers(10). -

A Critical Examination of the Idea of Evidence‑Based Policymaking

A critical examination of the idea of evidence‑based policymaking KARI PAHLMAN Abstract Since the election of the Labour Government in the United Kingdom in the 1990s on the platform of ‘what matters is what works’, the notion that policy should be evidence-based has gained significant popularity. While in theory, no one would suggest that policy should be based on anything other than robust evidence, this paper critically examines this concept of evidence-based policymaking, exploring the various complexities within it. Specifically, it questions the political nature of policymaking, the idea of what actually counts as evidence, and highlights the way that evidence can be selectively framed to promote a particular agenda. This paper examines evidence-based policy within the realm of Indigenous policymaking in Australia. It concludes that the practice of evidence-based policymaking is not necessarily a guarantee of more robust, effective or successful policy, highlighting implications for future policymaking. Since the 1990s, there has been increasing concern for policymaking to be based on evidence, rather than political ideology or ‘program inertia’ (Nutley et al. 2009, pp. 1, 4; Cherney & Head 2010, p. 510; Lin & Gibson 2003, p. xvii; Kavanagh et al. 2003, p. 70). Evolving from the practice of evidence-based medicine, evidence-based policymaking has recently gained significant popularity, particularly in the social services sectors (Lin & Gibson 2003, p. xvii; Marston & Watts 2003, p. 147; Nutley et al. 2009, p. 4). It has been said that nowadays, ‘evidence is as necessary to political conviction as it is to criminal conviction’ (Solesbury 2001, p. 4). This paper will critically examine the idea of evidence-based policymaking, concluding that while research and evidence should necessarily be a part of the policymaking process and can be an important component to ensuring policy success, there are nevertheless significant complexities. -

Using Randomized Evaluations to Improve the Efficiency of US Healthcare Delivery

Using Randomized Evaluations to Improve the Efficiency of US Healthcare Delivery Amy Finkelstein Sarah Taubman MIT, J-PAL North America, and NBER MIT, J-PAL North America February 2015 Abstract: Randomized evaluations of interventions that may improve the efficiency of US healthcare delivery are unfortunately rare. Across top journals in medicine, health services research, and economics, less than 20 percent of studies of interventions in US healthcare delivery are randomized. By contrast, about 80 percent of studies of medical interventions are randomized. The tide may be turning toward making randomized evaluations closer to the norm in healthcare delivery, as the relevant actors have an increasing need for rigorous evidence of what interventions work and why. At the same time, the increasing availability of administrative data that enables high-quality, low-cost RCTs and of new sources of funding that support RCTs in healthcare delivery make them easier to conduct. We suggest a number of design choices that can enhance the feasibility and impact of RCTs on US healthcare delivery including: greater reliance on existing administrative data; measuring a wide range of outcomes on healthcare costs, health, and broader economic measures; and designing experiments in a way that sheds light on underlying mechanisms. Finally, we discuss some of the more common concerns raised about the feasibility and desirability of healthcare RCTs and when and how these can be overcome. _____________________________ We are grateful to Innessa Colaiacovo, Lizi Chen, and Belinda Tang for outstanding research assistance, to Katherine Baicker, Mary Ann Bates, Kelly Bidwell, Joe Doyle, Mireille Jacobson, Larry Katz, Adam Sacarny, Jesse Shapiro, and Annetta Zhou for helpful comments, and to the Laura and John Arnold Foundation for financial support. -

Interpreting Indirect Treatment Comparisons and Network Meta

VALUE IN HEALTH 14 (2011) 417–428 available at www.sciencedirect.com journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jval SCIENTIFIC REPORT Interpreting Indirect Treatment Comparisons and Network Meta-Analysis for Health-Care Decision Making: Report of the ISPOR Task Force on Indirect Treatment Comparisons Good Research Practices: Part 1 Jeroen P. Jansen, PhD1,*, Rachael Fleurence, PhD2, Beth Devine, PharmD, MBA, PhD3, Robbin Itzler, PhD4, Annabel Barrett, BSc5, Neil Hawkins, PhD6, Karen Lee, MA7, Cornelis Boersma, PhD, MSc8, Lieven Annemans, PhD9, Joseph C. Cappelleri, PhD, MPH10 1Mapi Values, Boston, MA, USA; 2Oxford Outcomes, Bethesda, MD, USA; 3Pharmaceutical Outcomes Research and Policy Program, School of Pharmacy, School of Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA; 4Merck Research Laboratories, North Wales, PA, USA; 5Eli Lilly and Company Ltd., Windlesham, Surrey, UK; 6Oxford Outcomes Ltd., Oxford, UK; 7Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH), Ottawa, ON, Canada; 8University of Groningen / HECTA, Groningen, The Netherlands; 9University of Ghent, Ghent, Belgium; 10Pfizer Inc., New London, CT, USA ABSTRACT Evidence-based health-care decision making requires comparisons of all of randomized, controlled trials allow multiple treatment comparisons of relevant competing interventions. In the absence of randomized, con- competing interventions. Next, an introduction to the synthesis of the avail- trolled trials involving a direct comparison of all treatments of interest, able evidence with a focus on terminology, assumptions, validity, and statis- indirect treatment comparisons and network meta-analysis provide use- tical methods is provided, followed by advice on critically reviewing and in- ful evidence for judiciously selecting the best choice(s) of treatment. terpreting an indirect treatment comparison or network meta-analysis to Mixed treatment comparisons, a special case of network meta-analysis, inform decision making. -

Patient Reported Outcomes (PROS) in Performance Measurement

Patient-Reported Outcomes Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 2 Defining Patient-Reported Outcomes ............................................................................................ 2 How Are PROs Used? ............................................................................................................................ 3 Measuring research study endpoints ........................................................................................................ 3 Monitoring adverse events in clinical research ..................................................................................... 3 Monitoring symptoms, patient satisfaction, and health care performance ................................ 3 Example from the NIH Collaboratory ................................................................................................................... 4 Measuring PROs: Instruments, Item Banks, and Devices ....................................................... 5 PRO Instruments ............................................................................................................................................... 5 Item Banks........................................................................................................................................................... 8 Devices ................................................................................................................................................................. -

A National Strategy to Develop Pragmatic Clinical Trials Infrastructure

A National Strategy to Develop Pragmatic Clinical Trials Infrastructure Thomas W. Concannon, Ph.D.1,2, Jeanne-Marie Guise, M.D., M.P.H.3, Rowena J. Dolor, M.D., M.H.S.4, Paul Meissner, M.S.P.H.5, Sean Tunis, M.D., M.P.H.6, Jerry A. Krishnan, M.D., Ph.D.7,8, Wilson D. Pace, M.D.9, Joel Saltz, M.D., Ph.D.10, William R. Hersh, M.D.3, Lloyd Michener, M.D.4, and Timothy S. Carey, M.D., M.P.H.11 Abstract An important challenge in comparative effectiveness research is the lack of infrastructure to support pragmatic clinical trials, which com- pare interventions in usual practice settings and subjects. These trials present challenges that differ from those of classical efficacy trials, which are conducted under ideal circumstances, in patients selected for their suitability, and with highly controlled protocols. In 2012, we launched a 1-year learning network to identify high-priority pragmatic clinical trials and to deploy research infrastructure through the NIH Clinical and Translational Science Awards Consortium that could be used to launch and sustain them. The network and infrastructure were initiated as a learning ground and shared resource for investigators and communities interested in developing pragmatic clinical trials. We followed a three-stage process of developing the network, prioritizing proposed trials, and implementing learning exercises that culminated in a 1-day network meeting at the end of the year. The year-long project resulted in five recommendations related to developing the network, enhancing community engagement, addressing regulatory challenges, advancing information technology, and developing research methods. -

Health Research Policy and Systems Provided by Pubmed Central Biomed Central

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE Health Research Policy and Systems provided by PubMed Central BioMed Central Guide Open Access SUPPORT Tools for evidence-informed health Policymaking (STP) 17: Dealing with insufficient research evidence Andrew D Oxman*1, John N Lavis2, Atle Fretheim3 and Simon Lewin4 Address: 1Norwegian Knowledge Centre for the Health Services, P.O. Box 7004, St. Olavs plass, N-0130 Oslo, Norway, 2Centre for Health Economics and Policy Analysis, Department of Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, and Department of Political Science, McMaster University, 1200 Main St. West, HSC-2D3, Hamilton, ON, Canada, L8N 3Z5, 3Norwegian Knowledge Centre for the Health Services, P.O. Box 7004, St. Olavs plass, N-0130 Oslo, Norway; Section for International Health, Institute of General Practice and Community Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Oslo, Norway and 4Norwegian Knowledge Centre for the Health Services, P.O. Box 7004, St. Olavs plass, N-0130 Oslo, Norway; Health Systems Research Unit, Medical Research Council of South Africa Email: Andrew D Oxman* - [email protected]; John N Lavis - [email protected]; Atle Fretheim - [email protected]; Simon Lewin - [email protected] * Corresponding author Published: 16 December 2009 <supplement>byof thethe fundersEuropean had<title> Commission's a role <p>SUPPORT in drafting, 6th Framework revising Tools for or evidence-informedINCOapproving programme, the content health contract of thisPolicymaking 031939. series.</note> The (STP)</p> Norwegian </sponsor> </title> Agency <note>Guides</note> <editor>Andy for Development Oxman Cooperation<url>http://www.biomedcentral.com/content/pdf/1478-4505-7-S1-info.pdf</url> and Stephan (N Hanney</editor>orad), the Alliance <sponsor> for Health <note>This Policy and seriesSystems of articlesResearch, was and prepared the </supplement> Milbank as part Memorial of the SUPPORT Fund provided project, additional which wasfunding. -

Iain Chalmers Coordinator, James Lind Initiative GIMBE Convention

La campagna Lancet-REWARD: Some highlights over the past 40 years of ridurre gli sprechi e premiare my association with Italian colleagues il rigore scientifico Iain Chalmers Coordinator, James Lind Initiative GIMBE Convention Nazionale Bologna, 9 novembre 2016 1 Established 1994 2015 2012 1994 La campagna Lancet-REWARD: ridurre gli sprechi e premiare il rigore scientifico Evolution of concern about waste in research What should we think about researchers who use the wrong techniques, use the right techniques wrongly, misinterpret their results, report their results selectively, cite the literature selectively, and draw unjustified conclusions? We should be appalled. Yet numerous studies of the medical literature, in both general and specialist journals, have shown that all of the above phenomena are common. This is surely a scandal. We need less research, better research, and research done for the right reasons. 2 Recent evolution of concern about waste in research 2009 2 2014 42 2015 236 Lancet Adding Value, Reducing Lancet Adding Value, Reducing Waste 2014 Waste 2014 www.researchwaste.net www.researchwaste.net NIHR Adding Value in Research NIHR Adding Value in Research Framework Framework Lancet Adding Value, Reducing Waste 2014 www.researchwaste.net NIHR Adding Value in Research Framework 1. Waste resulting from funding and endorsing unnecessary or badly designed research 3 Alessandro Liberati Reports of new research should begin and end with systematic reviews of what is already known. Reports of new research should begin and end with systematic reviews of what is already known. Failure to do this has resulted in avoidable suffering and death. 4 Inappropriate continued use of placebo controls in clinical trials assessing the effects on death of antibiotic prophylaxis for colorectal surgery Horn J, Limburg M. -

Evidence-Based Medicine and Why Should I Care?

New Horizons Symposium Papers What Is Evidence-Based Medicine and Why Should I Care? Dean R Hess PhD RRT FAARC Introduction Is There a Problem? What Is Evidence-Based Medicine? Hierarchy of Evidence Finding the Evidence Examining the Evidence for a Diagnosis Test Examining the Evidence for a Therapy Meta-Analysis Why Isn’t the Best Evidence Implemented Into Practice? Summary The principles of evidence-based medicine provide the tools to incorporate the best evidence into everyday practice. Evidence-based medicine is the integration of individual clinical expertise with the best available research evidence from systematic research and the patient’s values and expec- tations. A hierarchy of evidence can be used to assess the strength of evidence upon which clinical decisions are made, with randomized studies at the top of the hierarchy. The efficient approach to finding the best evidence is to identify a systematic review or evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Calculated metrics, such as sensitivity, specificity, receiver-operating-characteristic curves, and likelihood ratios, can be used to examine the evidence for a diagnostic test. High-level studies of a therapy are prospective, randomized, blinded, placebo-controlled, have a concealed allocation, have a parallel design, and assess patient-important outcomes. Metrics used to assess the evidence for a therapy include event rate, relative risk, relative risk reduction, absolute risk re- duction, number needed to treat, and odds ratio. Although not all tenets of evidence-based medicine are universally accepted, the principles of evidence-based medicine nonetheless provide a valuable approach to respiratory care practice. Key words: likelihood ratio, meta-analysis, number needed to treat, receiver operating characteristic curve, relative risk, sensitivity, specificity, systematic review, evidence-based medicine. -

Working with Bipolar Disorder During the Covid-19 Pandemic: Both Crisis and Opportunity

Journal Articles 2020 Working with bipolar disorder during the covid-19 pandemic: Both crisis and opportunity E. A. Youngstrom S. P. Hinshaw A. Stefana J. Chen K. Michael See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://academicworks.medicine.hofstra.edu/articles Part of the Psychiatry Commons Recommended Citation Youngstrom EA, Hinshaw SP, Stefana A, Chen J, Michael K, Van Meter A, Maxwell V, Michalak EE, Choplin EG, Vieta E, . Working with bipolar disorder during the covid-19 pandemic: Both crisis and opportunity. 2020 Jan 01; 7(1):Article 6925 [ p.]. Available from: https://academicworks.medicine.hofstra.edu/articles/ 6925. Free full text article. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine Academic Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine Academic Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors E. A. Youngstrom, S. P. Hinshaw, A. Stefana, J. Chen, K. Michael, A. Van Meter, V. Maxwell, E. E. Michalak, E. G. Choplin, E. Vieta, and +3 additional authors This article is available at Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine Academic Works: https://academicworks.medicine.hofstra.edu/articles/6925 WikiJournal of Medicine, 2020, 7(1):5 doi: 10.15347/wjm/2020.005 Encyclopedic Review Article What are Systematic Reviews? Jack Nunn¹* and Steven Chang¹ et al. Abstract Systematic reviews are a type of review that uses repeatable analytical methods to collect secondary data and analyse it. Systematic reviews are a type of evidence synthesis which formulate research questions that are broad or narrow in scope, and identify and synthesize data that directly relate to the systematic review question.[1] While some people might associate ‘systematic review’ with 'meta-analysis', there are multiple kinds of review which can be defined as ‘systematic’ which do not involve a meta-analysis. -

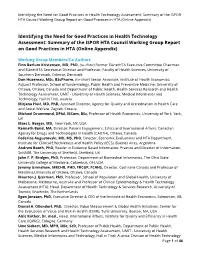

Identifying the Need for Good Practices in Health Technology

Identifying the Need for Good Practices in Health Technology Assessment: Summary of the ISPOR HTA Council Working Group Report on Good Practices in HTA (Online Appendix) Identifying the Need for Good Practices in Health Technology Assessment: Summary of the ISPOR HTA Council Working Group Report on Good Practices in HTA (Online Appendix) Working Group Members/Co-Authors Finn Børlum Kristensen, MD, PhD, (co-chair) Former EUnetHTA Executive Committee Chairman and EUnetHTA Secretariat Director and Professor, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark Don Husereau, MSc, BScPharm, (co-chair) Senior Associate, Institute of Health Economics; Adjunct Professor, School of Epidemiology, Public Health and Preventive Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada and Department of Public Health, Health Services Research and Health Technology Assessment, UMIT - University of Health Sciences, Medical Informatics and Technology, Hall in Tirol, Austria Mirjana Huić, MD, PhD, Assistant Director, Agency for Quality and Accreditation in Health Care and Social Welfare, Zagreb, Croatia Michael Drummond, DPhil, MCom, BSc, Professor of Health Economics, University of York, York, UK Marc L. Berger, MD, New York, NY, USA Kenneth Bond, MA, Director, Patient Engagement, Ethics and International Affairs, Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH), Ottawa, Canada Federico Augustovski, MD, MS, PhD, Director, Economic Evaluations and HTA Department, Institute for Clinical Effectiveness and Health Policy (IECS), Buenos Aires, Argentina Andrew Booth, PhD, Reader in Evidence Based Information Practice and Director of Information, ScHARR, The University of Sheffield, Sheffield, UK John F. P. Bridges, PhD, Professor, Department of Biomedical Informatics, The Ohio State University College of Medicine, Columbus, OH, USA Jeremy Grimshaw, MBCHB, PHD, FRCGP, FCAHS, Director, Cochrane Canada and Professor of Medicine,University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada Maarten J.