Interpreting Indirect Treatment Comparisons and Network Meta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Explanatory to Pragmatic Clinical Trials: a New Era for Effectiveness Research

From Explanatory to Pragmatic Clinical Trials: A New Era for Effectiveness Research Jerry Jarvik, M.D., M.P.H. Professor of Radiology, Neurological Surgery and Health Services Adjunct Professor Orthopedic Surgery & Sports Medicine and Pharmacy Director, Comparative Effectiveness, Cost and Outcomes Research Center (CECORC) UTSW April 2018 Acknowledgements •NIH: UH2 AT007766; UH3 AT007766 •NIH P30AR072572 •PCORI: CE-12-11-4469 Disclosures Physiosonix (ultrasound company): Founder/stockholder UpToDate: Section Editor Evidence-Based Neuroimaging Diagnosis and Treatment (Springer): Co-Editor The Big Picture Comparative Effectiveness Evidence Based Practice Health Policy Learning Healthcare System So we need to generate evidence Challenge #1: Clinical research is slow • Tradi>onal RCTs are slow and expensive— and rarely produce findings that are easily put into prac>ce. • In fact, it takes an average of 17 ye ars before research findings Howlead pragmaticto widespread clinical trials canchanges improve in care. practice & policy Challenge #1: Clinical research is slow “…rarely produce findings that are easily put into prac>ce.” Efficacy vs. Effectiveness Efficacy vs. Effectiveness • Efficacy: can it work under ideal conditions • Effectiveness: does it work under real-world conditions Challenge #2: Clinical research is not relevant to practice • Tradi>onal RCTs study efficacy “If we want of txs for carefully selected more evidence- popula>ons under ideal based pr actice, condi>ons. we need more • Difficult to translate to real practice-based evidence.” world. Green, LW. American Journal • When implemented into of Public Health, 2006. How pragmatic clinical trials everyday clinical prac>ce, oZen seecan a “ voltage improve drop practice”— drama>c & decreasepolicy from efficacy to effec>veness. -

Using Randomized Evaluations to Improve the Efficiency of US Healthcare Delivery

Using Randomized Evaluations to Improve the Efficiency of US Healthcare Delivery Amy Finkelstein Sarah Taubman MIT, J-PAL North America, and NBER MIT, J-PAL North America February 2015 Abstract: Randomized evaluations of interventions that may improve the efficiency of US healthcare delivery are unfortunately rare. Across top journals in medicine, health services research, and economics, less than 20 percent of studies of interventions in US healthcare delivery are randomized. By contrast, about 80 percent of studies of medical interventions are randomized. The tide may be turning toward making randomized evaluations closer to the norm in healthcare delivery, as the relevant actors have an increasing need for rigorous evidence of what interventions work and why. At the same time, the increasing availability of administrative data that enables high-quality, low-cost RCTs and of new sources of funding that support RCTs in healthcare delivery make them easier to conduct. We suggest a number of design choices that can enhance the feasibility and impact of RCTs on US healthcare delivery including: greater reliance on existing administrative data; measuring a wide range of outcomes on healthcare costs, health, and broader economic measures; and designing experiments in a way that sheds light on underlying mechanisms. Finally, we discuss some of the more common concerns raised about the feasibility and desirability of healthcare RCTs and when and how these can be overcome. _____________________________ We are grateful to Innessa Colaiacovo, Lizi Chen, and Belinda Tang for outstanding research assistance, to Katherine Baicker, Mary Ann Bates, Kelly Bidwell, Joe Doyle, Mireille Jacobson, Larry Katz, Adam Sacarny, Jesse Shapiro, and Annetta Zhou for helpful comments, and to the Laura and John Arnold Foundation for financial support. -

Patient Reported Outcomes (PROS) in Performance Measurement

Patient-Reported Outcomes Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 2 Defining Patient-Reported Outcomes ............................................................................................ 2 How Are PROs Used? ............................................................................................................................ 3 Measuring research study endpoints ........................................................................................................ 3 Monitoring adverse events in clinical research ..................................................................................... 3 Monitoring symptoms, patient satisfaction, and health care performance ................................ 3 Example from the NIH Collaboratory ................................................................................................................... 4 Measuring PROs: Instruments, Item Banks, and Devices ....................................................... 5 PRO Instruments ............................................................................................................................................... 5 Item Banks........................................................................................................................................................... 8 Devices ................................................................................................................................................................. -

A National Strategy to Develop Pragmatic Clinical Trials Infrastructure

A National Strategy to Develop Pragmatic Clinical Trials Infrastructure Thomas W. Concannon, Ph.D.1,2, Jeanne-Marie Guise, M.D., M.P.H.3, Rowena J. Dolor, M.D., M.H.S.4, Paul Meissner, M.S.P.H.5, Sean Tunis, M.D., M.P.H.6, Jerry A. Krishnan, M.D., Ph.D.7,8, Wilson D. Pace, M.D.9, Joel Saltz, M.D., Ph.D.10, William R. Hersh, M.D.3, Lloyd Michener, M.D.4, and Timothy S. Carey, M.D., M.P.H.11 Abstract An important challenge in comparative effectiveness research is the lack of infrastructure to support pragmatic clinical trials, which com- pare interventions in usual practice settings and subjects. These trials present challenges that differ from those of classical efficacy trials, which are conducted under ideal circumstances, in patients selected for their suitability, and with highly controlled protocols. In 2012, we launched a 1-year learning network to identify high-priority pragmatic clinical trials and to deploy research infrastructure through the NIH Clinical and Translational Science Awards Consortium that could be used to launch and sustain them. The network and infrastructure were initiated as a learning ground and shared resource for investigators and communities interested in developing pragmatic clinical trials. We followed a three-stage process of developing the network, prioritizing proposed trials, and implementing learning exercises that culminated in a 1-day network meeting at the end of the year. The year-long project resulted in five recommendations related to developing the network, enhancing community engagement, addressing regulatory challenges, advancing information technology, and developing research methods. -

Evidence-Based Medicine: Is It a Bridge Too Far?

Fernandez et al. Health Research Policy and Systems (2015) 13:66 DOI 10.1186/s12961-015-0057-0 REVIEW Open Access Evidence-based medicine: is it a bridge too far? Ana Fernandez1*, Joachim Sturmberg2, Sue Lukersmith3, Rosamond Madden3, Ghazal Torkfar4, Ruth Colagiuri4 and Luis Salvador-Carulla5 Abstract Aims: This paper aims to describe the contextual factors that gave rise to evidence-based medicine (EBM), as well as its controversies and limitations in the current health context. Our analysis utilizes two frameworks: (1) a complex adaptive view of health that sees both health and healthcare as non-linear phenomena emerging from their different components; and (2) the unified approach to the philosophy of science that provides a new background for understanding the differences between the phases of discovery, corroboration, and implementation in science. Results: The need for standardization, the development of clinical epidemiology, concerns about the economic sustainability of health systems and increasing numbers of clinical trials, together with the increase in the computer’s ability to handle large amounts of data, have paved the way for the development of the EBM movement. It was quickly adopted on the basis of authoritative knowledge rather than evidence of its own capacity to improve the efficiency and equity of health systems. The main problem with the EBM approach is the restricted and simplistic approach to scientific knowledge, which prioritizes internal validity as the major quality of the studies to be included in clinical guidelines. As a corollary, the preferred method for generating evidence is the explanatory randomized controlled trial. This method can be useful in the phase of discovery but is inadequate in the field of implementation, which needs to incorporate additional information including expert knowledge, patients’ values and the context. -

Evidence-Based Medicine and Why Should I Care?

New Horizons Symposium Papers What Is Evidence-Based Medicine and Why Should I Care? Dean R Hess PhD RRT FAARC Introduction Is There a Problem? What Is Evidence-Based Medicine? Hierarchy of Evidence Finding the Evidence Examining the Evidence for a Diagnosis Test Examining the Evidence for a Therapy Meta-Analysis Why Isn’t the Best Evidence Implemented Into Practice? Summary The principles of evidence-based medicine provide the tools to incorporate the best evidence into everyday practice. Evidence-based medicine is the integration of individual clinical expertise with the best available research evidence from systematic research and the patient’s values and expec- tations. A hierarchy of evidence can be used to assess the strength of evidence upon which clinical decisions are made, with randomized studies at the top of the hierarchy. The efficient approach to finding the best evidence is to identify a systematic review or evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Calculated metrics, such as sensitivity, specificity, receiver-operating-characteristic curves, and likelihood ratios, can be used to examine the evidence for a diagnostic test. High-level studies of a therapy are prospective, randomized, blinded, placebo-controlled, have a concealed allocation, have a parallel design, and assess patient-important outcomes. Metrics used to assess the evidence for a therapy include event rate, relative risk, relative risk reduction, absolute risk re- duction, number needed to treat, and odds ratio. Although not all tenets of evidence-based medicine are universally accepted, the principles of evidence-based medicine nonetheless provide a valuable approach to respiratory care practice. Key words: likelihood ratio, meta-analysis, number needed to treat, receiver operating characteristic curve, relative risk, sensitivity, specificity, systematic review, evidence-based medicine. -

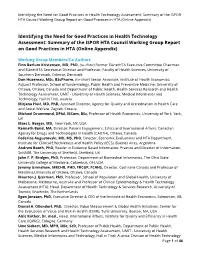

Identifying the Need for Good Practices in Health Technology

Identifying the Need for Good Practices in Health Technology Assessment: Summary of the ISPOR HTA Council Working Group Report on Good Practices in HTA (Online Appendix) Identifying the Need for Good Practices in Health Technology Assessment: Summary of the ISPOR HTA Council Working Group Report on Good Practices in HTA (Online Appendix) Working Group Members/Co-Authors Finn Børlum Kristensen, MD, PhD, (co-chair) Former EUnetHTA Executive Committee Chairman and EUnetHTA Secretariat Director and Professor, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark Don Husereau, MSc, BScPharm, (co-chair) Senior Associate, Institute of Health Economics; Adjunct Professor, School of Epidemiology, Public Health and Preventive Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada and Department of Public Health, Health Services Research and Health Technology Assessment, UMIT - University of Health Sciences, Medical Informatics and Technology, Hall in Tirol, Austria Mirjana Huić, MD, PhD, Assistant Director, Agency for Quality and Accreditation in Health Care and Social Welfare, Zagreb, Croatia Michael Drummond, DPhil, MCom, BSc, Professor of Health Economics, University of York, York, UK Marc L. Berger, MD, New York, NY, USA Kenneth Bond, MA, Director, Patient Engagement, Ethics and International Affairs, Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH), Ottawa, Canada Federico Augustovski, MD, MS, PhD, Director, Economic Evaluations and HTA Department, Institute for Clinical Effectiveness and Health Policy (IECS), Buenos Aires, Argentina Andrew Booth, PhD, Reader in Evidence Based Information Practice and Director of Information, ScHARR, The University of Sheffield, Sheffield, UK John F. P. Bridges, PhD, Professor, Department of Biomedical Informatics, The Ohio State University College of Medicine, Columbus, OH, USA Jeremy Grimshaw, MBCHB, PHD, FRCGP, FCAHS, Director, Cochrane Canada and Professor of Medicine,University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada Maarten J. -

Levels of Evidence

Levels of Evidence PLEASE NOTE: Evidence levels are only used for research involving human subjects. Basic science and animal studies should be listed as NA. Level Therapy/Prevention or Etiology/Harm Prognosis Study Study 1a Systematic review of randomized Systematic review of prospective cohort controlled trials studies 1b Individual randomized controlled trial Individual prospective cohort study 2a Systematic review of cohort studies Systematic review of retrospective cohort studies 2b Individual cohort study Individual retrospective cohort study 2c “Outcomes research” “Outcomes research” 3a Systematic review of case-control studies 3b Individual case-control study 4 Case series (with or without comparison) Case series (with or without comparison) 5 Expert opinion Expert opinion NA Animal studies and basic research Animal studies and basic research Case-Control Study. Case-control studies, which are always retrospective, compare those who have had an outcome or event (cases) with those who have not (controls). Cases and controls are then evaluated for exposure to various risk factors. Cases and controls generally are matched according to specific characteristics (eg, age, sex, or duration of disease). Case Series. A case series describes characteristics of a group of patients with a particular disease or patients who had undergone a particular procedure. A case series may also involve observation of larger units such as groups of hospitals or municipalities, as well as smaller units such as laboratory samples. Case series may be used to formulate a case definition of a disease or describe the experience of an individual or institution in treating a disease or performing a type of procedure. A case series is not used to test a hypothesis because there is no comparison group. -

Health Outcomes Research HIM 6810 Health Outcomes Research (HIM 6810)

Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs School of Biomedical Sciences Morsani College of Medicine Health Outcomes Research HIM 6810 Health Outcomes Research (HIM 6810) Course Director: Michael J. Barber, M.Sc., D.Phil. (813) 974-4181 (813) 974-4317 Canvas integrated email system Course Format: This course is delivered online through the USF Health Online Portal (http://www.usfhealthonline.com/). Course Objectives: ealth Outcomes Research (HIM 6810) is a graduate-level course designed to introduce students to fundamentals of H health outcome and clinical trial research. It explores the principles and methods used to obtain quantitative evidence on the effects of interventions on the diagnosis, etiology, and prognosis of disease. Health outcomes research is a broad term used to categorize research concerned with the effectiveness of public health interventions and health services. According to the US Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, outcomes research seeks to understand the end results of particular health care practices and interventions. End results include effects that people experience and care about, such as change in the ability to function. In particular, for individuals with chronic conditions, where cure is not always possible, end results include quality of life as well as mortality. By linking the care that people get to the outcomes they experience, outcomes research has become the key to developing better ways to monitor and improve the quality of care. Outcomes research is an integrated, multidisciplinary field that aims at improving the safety, effectiveness, equity, efficiency, timeliness, and patient-centeredness of practice and policy associated with healthcare research. It synthesizes aspects of other scientific and applied disciplines to solve clinical and policy research problems. -

Real-World Data in Pragmatic Trials

Real-world data in pragmatic trials Harold C. Sox ,MD The Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute Washington, DC Presenter Disclosure Information In compliance with the accrediting board policies, the American Diabetes Association requires the following disclosure to the participants: Name of Presenter Harold C. Sox, MD Disclosed no conflict of interest. The content of the talk does not necessarily reflect the policies of PCORI or its Board of Governors. Plan of the talk 1. The concepts and conduct of a pragmatic trial. 2. Real-world data: definitions and sources 3. ADAPTABLE: a network-based RCT comparing two doses of aspirin. 4. Use of real-world data in ADAPTABLE: advantages and pitfalls. 5. Challenges to interpreting pragmatic clinical trial results. Pragmatic Trials: history • 1967: Schwartz and Lellouch (J Chronic Disease): pragmatic and explanatory attitudes toward trials. • “This article makes no pretention to originality, nor to the provision of solutions; we hope we have clarified certain issues to the extent of encouraging further discussion.” • 1983-85: GISSI trial of thrombolysis in acute MI. • 2005: PRECIS-1 • “Finally, we stress that this article, building on earlier work from multiple investigators, describes a “work in progress.” • 2013: PRECIS-2 Pragmatic Efficacy Broad eligibility Narrow eligibility Flexible interventions Adhere to instructions Expert practitioners Typical practitioners Follow-up visits only as needed for care Frequent follow-up visits Objective clinical outcome Surrogate outcomes Usual efforts to insure adherence Close monitoring for adherence Addresses a clinical decision Addresses mechanism and concept Per Protocol analysis Intention to treat analysis Figure 1: The blank “wheel” of the pragmatic–explanatory continuum indicator summary (PRECIS) tool. -

Final Research Report

PATIENT-CENTERED OUTCOMES RESEARCH INSTITUTE FINAL RESEARCH REPORT Examining Health Outcomes for People Who Are Transgender Michael Goodman, MD, MPH; Rebecca Nash, MPH AFFILIATION: Emory University School of Public Health, Atlanta, Georgia Original Project Title: Comparative Risks and Benefits of Gender Reassignment Therapies PCORI ID: AD-12-11-4532 HSRProj ID: 20143115 _______________________________ To cite this document, please use: Goodman M, Nash R. (2019). Examining Health Outcomes for People Who Are Transgender. Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). https://doi.org/10.25302/2.2019.AD.12114532 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT .............................................................................................................................. 6 BACKGROUND ........................................................................................................................ 8 Transgender Health Issues and Knowledge Gaps ...................................................................... 8 Methodological Challenges Facing Transgender Health Studies ............................................. 10 Introducing Study of Transition, Outcomes, and Gender ........................................................ 11 Table 1. STRONG Project Timeline .................................................................................... 12 STAKEHOLDER INVOLVEMENT ............................................................................................... 13 Preliminary Survey .................................................................................................................. -

Pragmatic Clinical Trials for Real-World Evidence: Concept and Implementation

Cardiovasc Prev Pharmacother. 2020 Jul;2(3):85-98 Cardiovascular Prevention https://doi.org/10.36011/cpp.2020.2.e12 eISSN 2671-700X and Pharmacotherapy Special Article Pragmatic Clinical Trials for Real-World Evidence: Concept and Implementation Na-Young Jeong , BS, Seon-Ha Kim , BS, Eunsun Lim , BS, Nam-Kyong Choi , PhD Department of Health Convergence, Ewha Womans University, Seoul, Korea Received: Jun 30, 2020 ABSTRACT Accepted: Jul 28, 2020 Correspondence to The importance of real-world evidence (RWE) has been highlighted in recent years, and Nam-Kyong Choi, PhD the limitations of the classical randomized controlled trials, also known as explanatory Department of Health Convergence, Ewha clinical trials (ECTs), have been emphasized. Post-marketing observational studies have Womans University, 52 Ewhayeodae-gil, several problems, such as biases and incomparability between patient groups, and RWE Seodaemun-gu, Seoul 03760, Korea. E-mail: [email protected] can only be obtained after a certain period. Therefore, pragmatic clinical trials (PCTs) have garnered attention as an alternative to obtaining scientifically robust RWE in a relatively Copyright © 2020. Korean Society of short time. PCTs are clinical trials that have a pragmatic concept, i.e., the opposite of ECTs Cardiovascular Disease Prevention; Korean and are intended to help decision makers by evaluating the effectiveness of interventions in Society of Cardiovascular Pharmacotherapy. routine clinical practice. The characteristics of PCTs are the inclusion of various patients in This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons clinical practice, recruitment of patients in heterogeneous settings, and comparison with Attribution Non-Commercial License (https:// actual clinical treatments rather than a placebo.