Using Randomized Evaluations to Improve the Efficiency of US Healthcare Delivery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Explanatory to Pragmatic Clinical Trials: a New Era for Effectiveness Research

From Explanatory to Pragmatic Clinical Trials: A New Era for Effectiveness Research Jerry Jarvik, M.D., M.P.H. Professor of Radiology, Neurological Surgery and Health Services Adjunct Professor Orthopedic Surgery & Sports Medicine and Pharmacy Director, Comparative Effectiveness, Cost and Outcomes Research Center (CECORC) UTSW April 2018 Acknowledgements •NIH: UH2 AT007766; UH3 AT007766 •NIH P30AR072572 •PCORI: CE-12-11-4469 Disclosures Physiosonix (ultrasound company): Founder/stockholder UpToDate: Section Editor Evidence-Based Neuroimaging Diagnosis and Treatment (Springer): Co-Editor The Big Picture Comparative Effectiveness Evidence Based Practice Health Policy Learning Healthcare System So we need to generate evidence Challenge #1: Clinical research is slow • Tradi>onal RCTs are slow and expensive— and rarely produce findings that are easily put into prac>ce. • In fact, it takes an average of 17 ye ars before research findings Howlead pragmaticto widespread clinical trials canchanges improve in care. practice & policy Challenge #1: Clinical research is slow “…rarely produce findings that are easily put into prac>ce.” Efficacy vs. Effectiveness Efficacy vs. Effectiveness • Efficacy: can it work under ideal conditions • Effectiveness: does it work under real-world conditions Challenge #2: Clinical research is not relevant to practice • Tradi>onal RCTs study efficacy “If we want of txs for carefully selected more evidence- popula>ons under ideal based pr actice, condi>ons. we need more • Difficult to translate to real practice-based evidence.” world. Green, LW. American Journal • When implemented into of Public Health, 2006. How pragmatic clinical trials everyday clinical prac>ce, oZen seecan a “ voltage improve drop practice”— drama>c & decreasepolicy from efficacy to effec>veness. -

Toward an Ethical Experiment

TOWARD AN ETHICAL EXPERIMENT By Yusuke Narita April 2018 COWLES FOUNDATION DISCUSSION PAPER NO. 2127 COWLES FOUNDATION FOR RESEARCH IN ECONOMICS YALE UNIVERSITY Box 208281 New Haven, Connecticut 06520-8281 http://cowles.yale.edu/ ∗ Toward an Ethical Experiment y Yusuke Narita April 17, 2018 Abstract Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) enroll hundreds of millions of subjects and in- volve many human lives. To improve subjects' welfare, I propose an alternative design of RCTs that I call Experiment-as-Market (EXAM). EXAM Pareto optimally randomly assigns each treatment to subjects predicted to experience better treatment effects or to subjects with stronger preferences for the treatment. EXAM is also asymptotically incentive compatible for preference elicitation. Finally, EXAM unbiasedly estimates any causal effect estimable with standard RCTs. I quantify the welfare, incentive, and information properties by applying EXAM to a water cleaning experiment in Kenya (Kremer et al., 2011). Compared to standard RCTs, EXAM substantially improves subjects' predicted well-being while reaching similar treatment effect estimates with similar precision. Keywords: Research Ethics, Clinical Trial, Social Experiment, A/B Test, Market De- sign, Causal Inference, Development Economics, Spring Protection, Discrete Choice ∗I am grateful to Dean Karlan for a conversation that inspired this project; Joseph Moon for industrial and institutional input; Jason Abaluck, Josh Angrist, Tim Armstrong, Sylvain Chassang, Naoki Egami, Peter Hull, Costas Meghir, Bobby Pakzad-Hurson, -

Interpreting Indirect Treatment Comparisons and Network Meta

VALUE IN HEALTH 14 (2011) 417–428 available at www.sciencedirect.com journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jval SCIENTIFIC REPORT Interpreting Indirect Treatment Comparisons and Network Meta-Analysis for Health-Care Decision Making: Report of the ISPOR Task Force on Indirect Treatment Comparisons Good Research Practices: Part 1 Jeroen P. Jansen, PhD1,*, Rachael Fleurence, PhD2, Beth Devine, PharmD, MBA, PhD3, Robbin Itzler, PhD4, Annabel Barrett, BSc5, Neil Hawkins, PhD6, Karen Lee, MA7, Cornelis Boersma, PhD, MSc8, Lieven Annemans, PhD9, Joseph C. Cappelleri, PhD, MPH10 1Mapi Values, Boston, MA, USA; 2Oxford Outcomes, Bethesda, MD, USA; 3Pharmaceutical Outcomes Research and Policy Program, School of Pharmacy, School of Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA; 4Merck Research Laboratories, North Wales, PA, USA; 5Eli Lilly and Company Ltd., Windlesham, Surrey, UK; 6Oxford Outcomes Ltd., Oxford, UK; 7Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH), Ottawa, ON, Canada; 8University of Groningen / HECTA, Groningen, The Netherlands; 9University of Ghent, Ghent, Belgium; 10Pfizer Inc., New London, CT, USA ABSTRACT Evidence-based health-care decision making requires comparisons of all of randomized, controlled trials allow multiple treatment comparisons of relevant competing interventions. In the absence of randomized, con- competing interventions. Next, an introduction to the synthesis of the avail- trolled trials involving a direct comparison of all treatments of interest, able evidence with a focus on terminology, assumptions, validity, and statis- indirect treatment comparisons and network meta-analysis provide use- tical methods is provided, followed by advice on critically reviewing and in- ful evidence for judiciously selecting the best choice(s) of treatment. terpreting an indirect treatment comparison or network meta-analysis to Mixed treatment comparisons, a special case of network meta-analysis, inform decision making. -

Patient Reported Outcomes (PROS) in Performance Measurement

Patient-Reported Outcomes Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 2 Defining Patient-Reported Outcomes ............................................................................................ 2 How Are PROs Used? ............................................................................................................................ 3 Measuring research study endpoints ........................................................................................................ 3 Monitoring adverse events in clinical research ..................................................................................... 3 Monitoring symptoms, patient satisfaction, and health care performance ................................ 3 Example from the NIH Collaboratory ................................................................................................................... 4 Measuring PROs: Instruments, Item Banks, and Devices ....................................................... 5 PRO Instruments ............................................................................................................................................... 5 Item Banks........................................................................................................................................................... 8 Devices ................................................................................................................................................................. -

A National Strategy to Develop Pragmatic Clinical Trials Infrastructure

A National Strategy to Develop Pragmatic Clinical Trials Infrastructure Thomas W. Concannon, Ph.D.1,2, Jeanne-Marie Guise, M.D., M.P.H.3, Rowena J. Dolor, M.D., M.H.S.4, Paul Meissner, M.S.P.H.5, Sean Tunis, M.D., M.P.H.6, Jerry A. Krishnan, M.D., Ph.D.7,8, Wilson D. Pace, M.D.9, Joel Saltz, M.D., Ph.D.10, William R. Hersh, M.D.3, Lloyd Michener, M.D.4, and Timothy S. Carey, M.D., M.P.H.11 Abstract An important challenge in comparative effectiveness research is the lack of infrastructure to support pragmatic clinical trials, which com- pare interventions in usual practice settings and subjects. These trials present challenges that differ from those of classical efficacy trials, which are conducted under ideal circumstances, in patients selected for their suitability, and with highly controlled protocols. In 2012, we launched a 1-year learning network to identify high-priority pragmatic clinical trials and to deploy research infrastructure through the NIH Clinical and Translational Science Awards Consortium that could be used to launch and sustain them. The network and infrastructure were initiated as a learning ground and shared resource for investigators and communities interested in developing pragmatic clinical trials. We followed a three-stage process of developing the network, prioritizing proposed trials, and implementing learning exercises that culminated in a 1-day network meeting at the end of the year. The year-long project resulted in five recommendations related to developing the network, enhancing community engagement, addressing regulatory challenges, advancing information technology, and developing research methods. -

Social Psychology

Social Psychology OUTLINE OF RESOURCES Introducing Social Psychology Lecture/Discussion Topic: Social Psychology’s Most Important Lessons (p. 853) Social Thinking The Fundamental Attribution Error Lecture/Discussion Topic: Attribution and Models of Helping (p. 856) Classroom Exercises: The Fundamental Attribution Error (p. 854) Students’ Perceptions of You (p. 855) Classroom Exercise/Critical Thinking Break: Biases in Explaining Events (p. 855) NEW Feature (Short) Film: The Lunch Date (p. 856) Worth Video Anthology: The Actor-Observer Difference in Attribution: Observe a Riot in Action* Attitudes and Actions Lecture/Discussion Topics: The Looking Glass Effect (p. 856) The Theory of Reasoned Action (p. 857) Actions Influence Attitudes (p. 857) The Justification of Effort (p. 858) Self-Persuasion (p. 859) Revisiting the Stanford Prison Experiment (p. 859) Abu Ghraib Prison and Social Psychology (p. 860) Classroom Exercise: Introducing Cognitive Dissonance Theory (p. 858) Worth Video Anthology: Zimbardo’s Stanford Prison Experiment* The Stanford Prison Experiment: The Power of the Situation* Social Influence Conformity: Complying With Social Pressures Lecture/Discussion Topics: Mimicry and Prosocial Behavior (p. 861) Social Exclusion and Mimicry (p. 861) The Seattle Windshield Pitting Epidemic (p. 862) Classroom Exercises: Suggestibility (p. 862) Social Influence (p. 863) Student Project: Violating a Social Norm (p. 863) Worth Video Anthology: Social Influence* NEW Liking and Imitation: The Sincerest Form of Flattery* Obedience: Following Orders Lecture/Discussion Topic: Obedience in Everyday Life (p. 865) Classroom Exercises: Obedience and Conformity (p. 864) Would You Obey? (p. 864) Wolves or Sheep? (p. 866) * Titles in the Worth Video Anthology are not described within the core resource unit. -

Evidence-Based Medicine: Is It a Bridge Too Far?

Fernandez et al. Health Research Policy and Systems (2015) 13:66 DOI 10.1186/s12961-015-0057-0 REVIEW Open Access Evidence-based medicine: is it a bridge too far? Ana Fernandez1*, Joachim Sturmberg2, Sue Lukersmith3, Rosamond Madden3, Ghazal Torkfar4, Ruth Colagiuri4 and Luis Salvador-Carulla5 Abstract Aims: This paper aims to describe the contextual factors that gave rise to evidence-based medicine (EBM), as well as its controversies and limitations in the current health context. Our analysis utilizes two frameworks: (1) a complex adaptive view of health that sees both health and healthcare as non-linear phenomena emerging from their different components; and (2) the unified approach to the philosophy of science that provides a new background for understanding the differences between the phases of discovery, corroboration, and implementation in science. Results: The need for standardization, the development of clinical epidemiology, concerns about the economic sustainability of health systems and increasing numbers of clinical trials, together with the increase in the computer’s ability to handle large amounts of data, have paved the way for the development of the EBM movement. It was quickly adopted on the basis of authoritative knowledge rather than evidence of its own capacity to improve the efficiency and equity of health systems. The main problem with the EBM approach is the restricted and simplistic approach to scientific knowledge, which prioritizes internal validity as the major quality of the studies to be included in clinical guidelines. As a corollary, the preferred method for generating evidence is the explanatory randomized controlled trial. This method can be useful in the phase of discovery but is inadequate in the field of implementation, which needs to incorporate additional information including expert knowledge, patients’ values and the context. -

Evidence-Based Medicine and Why Should I Care?

New Horizons Symposium Papers What Is Evidence-Based Medicine and Why Should I Care? Dean R Hess PhD RRT FAARC Introduction Is There a Problem? What Is Evidence-Based Medicine? Hierarchy of Evidence Finding the Evidence Examining the Evidence for a Diagnosis Test Examining the Evidence for a Therapy Meta-Analysis Why Isn’t the Best Evidence Implemented Into Practice? Summary The principles of evidence-based medicine provide the tools to incorporate the best evidence into everyday practice. Evidence-based medicine is the integration of individual clinical expertise with the best available research evidence from systematic research and the patient’s values and expec- tations. A hierarchy of evidence can be used to assess the strength of evidence upon which clinical decisions are made, with randomized studies at the top of the hierarchy. The efficient approach to finding the best evidence is to identify a systematic review or evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Calculated metrics, such as sensitivity, specificity, receiver-operating-characteristic curves, and likelihood ratios, can be used to examine the evidence for a diagnostic test. High-level studies of a therapy are prospective, randomized, blinded, placebo-controlled, have a concealed allocation, have a parallel design, and assess patient-important outcomes. Metrics used to assess the evidence for a therapy include event rate, relative risk, relative risk reduction, absolute risk re- duction, number needed to treat, and odds ratio. Although not all tenets of evidence-based medicine are universally accepted, the principles of evidence-based medicine nonetheless provide a valuable approach to respiratory care practice. Key words: likelihood ratio, meta-analysis, number needed to treat, receiver operating characteristic curve, relative risk, sensitivity, specificity, systematic review, evidence-based medicine. -

The Core Analytics of Randomized Experiments for Social Research

MDRC Working Papers on Research Methodology The Core Analytics of Randomized Experiments for Social Research Howard S. Bloom August 2006 This working paper is part of a series of publications by MDRC on alternative methods of evaluating the implementation and impacts of social and educational programs and policies. The paper will be published as a chapter in the forthcoming Handbook of Social Research by Sage Publications, Inc. Many thanks are due to Richard Dorsett, Carolyn Hill, Rob Hollister, and Charles Michalopoulos for their helpful suggestions on revising earlier drafts. This working paper was supported by the Judith Gueron Fund for Methodological Innovation in Social Policy Research at MDRC, which was created through gifts from the Annie E. Casey, Rocke- feller, Jerry Lee, Spencer, William T. Grant, and Grable Foundations. The findings and conclusions in this paper do not necessarily represent the official positions or poli- cies of the funders. Dissemination of MDRC publications is supported by the following funders that help finance MDRC’s public policy outreach and expanding efforts to communicate the results and implications of our work to policymakers, practitioners, and others: Alcoa Foundation, The Ambrose Monell Foundation, The Atlantic Philanthropies, Bristol-Myers Squibb Foundation, Open Society Institute, and The Starr Foundation. In addition, earnings from the MDRC Endowment help sustain our dis- semination efforts. Contributors to the MDRC Endowment include Alcoa Foundation, The Ambrose Monell Foundation, Anheuser-Busch Foundation, Bristol-Myers Squibb Foundation, Charles Stew- art Mott Foundation, Ford Foundation, The George Gund Foundation, The Grable Foundation, The Lizabeth and Frank Newman Charitable Foundation, The New York Times Company Foundation, Jan Nicholson, Paul H. -

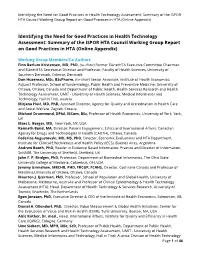

Identifying the Need for Good Practices in Health Technology

Identifying the Need for Good Practices in Health Technology Assessment: Summary of the ISPOR HTA Council Working Group Report on Good Practices in HTA (Online Appendix) Identifying the Need for Good Practices in Health Technology Assessment: Summary of the ISPOR HTA Council Working Group Report on Good Practices in HTA (Online Appendix) Working Group Members/Co-Authors Finn Børlum Kristensen, MD, PhD, (co-chair) Former EUnetHTA Executive Committee Chairman and EUnetHTA Secretariat Director and Professor, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark Don Husereau, MSc, BScPharm, (co-chair) Senior Associate, Institute of Health Economics; Adjunct Professor, School of Epidemiology, Public Health and Preventive Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada and Department of Public Health, Health Services Research and Health Technology Assessment, UMIT - University of Health Sciences, Medical Informatics and Technology, Hall in Tirol, Austria Mirjana Huić, MD, PhD, Assistant Director, Agency for Quality and Accreditation in Health Care and Social Welfare, Zagreb, Croatia Michael Drummond, DPhil, MCom, BSc, Professor of Health Economics, University of York, York, UK Marc L. Berger, MD, New York, NY, USA Kenneth Bond, MA, Director, Patient Engagement, Ethics and International Affairs, Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH), Ottawa, Canada Federico Augustovski, MD, MS, PhD, Director, Economic Evaluations and HTA Department, Institute for Clinical Effectiveness and Health Policy (IECS), Buenos Aires, Argentina Andrew Booth, PhD, Reader in Evidence Based Information Practice and Director of Information, ScHARR, The University of Sheffield, Sheffield, UK John F. P. Bridges, PhD, Professor, Department of Biomedical Informatics, The Ohio State University College of Medicine, Columbus, OH, USA Jeremy Grimshaw, MBCHB, PHD, FRCGP, FCAHS, Director, Cochrane Canada and Professor of Medicine,University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada Maarten J. -

Levels of Evidence

Levels of Evidence PLEASE NOTE: Evidence levels are only used for research involving human subjects. Basic science and animal studies should be listed as NA. Level Therapy/Prevention or Etiology/Harm Prognosis Study Study 1a Systematic review of randomized Systematic review of prospective cohort controlled trials studies 1b Individual randomized controlled trial Individual prospective cohort study 2a Systematic review of cohort studies Systematic review of retrospective cohort studies 2b Individual cohort study Individual retrospective cohort study 2c “Outcomes research” “Outcomes research” 3a Systematic review of case-control studies 3b Individual case-control study 4 Case series (with or without comparison) Case series (with or without comparison) 5 Expert opinion Expert opinion NA Animal studies and basic research Animal studies and basic research Case-Control Study. Case-control studies, which are always retrospective, compare those who have had an outcome or event (cases) with those who have not (controls). Cases and controls are then evaluated for exposure to various risk factors. Cases and controls generally are matched according to specific characteristics (eg, age, sex, or duration of disease). Case Series. A case series describes characteristics of a group of patients with a particular disease or patients who had undergone a particular procedure. A case series may also involve observation of larger units such as groups of hospitals or municipalities, as well as smaller units such as laboratory samples. Case series may be used to formulate a case definition of a disease or describe the experience of an individual or institution in treating a disease or performing a type of procedure. A case series is not used to test a hypothesis because there is no comparison group. -

Introduction To" Social Experimentation"

This PDF is a selection from an out-of-print volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: Social Experimentation Volume Author/Editor: Jerry A. Hausman and David A. Wise, eds. Volume Publisher: University of Chicago Press Volume ISBN: 0-226-31940-7 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/haus85-1 Publication Date: 1985 Chapter Title: Introduction to "Social Experimentation" Chapter Author: Jerry A. Hausman, David A. Wise Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c8371 Chapter pages in book: (p. 1 - 10) Introduction Jerry A. Hausman and Davis A. Wise During the past decade the United States government has spent over 500 million dollars on social experiments. The experiments attempt to deter- mine the potential effect of a policy option by trying it out on a group of subjects, some of whom are randomly assigned to a treatment group and are the recipients of the proposed policy, while others are assigned to a control group. The difference in the outcomes for the two groups is the estimated effect of the policy option. This approach is an alternative to making judgments about the effect of the proposed policy from infer- ences based on observational (survey) data, but without the advantages of randomization. While a few social experiments have been conducted in the past, this development is a relatively new approach to the evaluation of the effect of proposed government policies. Much of the $500 million has gone into transfer payments to the experimental subjects, most of whom have benefited from the experiments. But the most important question is whether the experiments have been successful in their primary goal of providing precise estimates of the effects of a proposed govern- ment policy.