RET 30 Cover +

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JACEK TRZEBUNIAK* Analysis of Development of the Tibetan Tulku

The Polish Journal of the Arts and Culture Nr 10 (2/2014) / ARTICLE JACEK TRZEBUNIAK* (Uniwersytet Jagielloński) Analysis of Development of the Tibetan Tulku System in Western Culture ABSTRACT With the development of Tibetan Buddhism in Europe and America, from the second half of the twentieth century, the phenomenon of recognising a person as a reincarnation of Bud- dhist teachers appeared in this part of the world. Tibetan masters expected that the identified person will serve important social and religious functions for Buddhist communities. How- ever, after several decades since the first recognitions, the Western tulkus do not play the same important role in the development of Buddhism, as tulkus in China, and the Tibetan communities in exile. The article analyses the cultural and social causes of the different functioning of tulku institution in Western societies. The article shows that a different un- derstanding of identity, power and hierarchy mean that tulkus do not play significant roles in the development of Buddhism in this part of the world. KEY WORDS religious studies, Tibetan Buddhism, tulku, West INTRODUCTION Tulku (Tib. sprul sku) is a person in Tibetan Buddhism tradition who is recog- nised as a reincarnation of a famous Buddhist master. The tradition originated in the 13th century in the Kagyu (Tib. bka’ brgyud) sect when students of the Dusum Khyenpa (Tib. dus gsum mkhyen pa), after his death, found a boy and * Wydział Filozoficzny, Katedra Porównawczych Studiów Cywilizacji Uniwersytet Jagielloński w Krakowie, Polska e-mail: [email protected] 116 Jacek Trzebuniak recognised him as a reincarnation of their master1. -

His Holiness the Karmapa, Ogyen Trinley Dorje, to Visit University of Redlands in Rare U.S

His Holiness the Karmapa, Ogyen Trinley Dorje, to visit University of Redlands in rare U.S. tour March 18, 2015 The University of Redlands will welcome His Holiness the Karmapa, Ogyen Trinley Dorje, to campus March 24, 2015, as the only Southern California stop on his third trip to the United States. Reigniting a years-long connection with the University and special bond with students, the Karmapa will interact with Redlands students, faculty, and alumni and accept an Honorary Doctor of Humane Letters degree, presented by University President Ralph Kuncl. He will then offer a public lecture, "Living Interdependence," at 7 p.m. in Memorial Chapel. The Karmapa heads the 900-year-old Karma Kagyu school of Tibetan Buddhism and guides millions of Buddhists around the world. At the age of 14, he made a dramatic escape from Tibet to India to be near His Holiness the Dalai Lama and his own lineage teachers. Currently 29 years old, the Karmapa is a leader of the new century. He created an eco- monastic movement with over 55 monasteries across the Himalayan region acting as centers of environmental activism. Leading on women's issues, he recently announced plans to establish full ordination for women, a step that will change the future of Tibetan Buddhism. His latest book, The Heart is Noble: Changing the World from the Inside Out, co-edited by University of Redlands Professor of Religious Studies and Virginia C. Hunsaker Distinguished Teaching Chair, Karen Derris, the Karmapa speaks to the younger generation on the major challenges facing society today, including gender issues, food justice, rampant consumerism and the environmental crisis. -

Guenther's Saraha: a Detailed Review of Ecstatic Spontaneity 111 ROGER JACKSON

J ournal of the international Association of Buddhist Studies Volume 17 • Number 1 • Summer 1994 HUGH B. URBAN and PAUL J. GRIFFITHS What Else Remains in Sunyata? An Investigation of Terms for Mental Imagery in the Madhyantavibhaga-Corpus 1 BROOK ZIPORYN Anti-Chan Polemics in Post Tang Tiantai 26 DING-HWA EVELYN HSIEH Yuan-wu K'o-ch'in's (1063-1135) Teaching of Ch'an Kung-an Practice: A Transition from the Literary Study of Ch'an Kung-an to the Practical JCan-hua Ch'an 66 ALLAN A. ANDREWS Honen and Popular Pure Land Piety: Assimilation and Transformation 96 ROGER JACKSON Guenther's Saraha: A Detailed Review of Ecstatic Spontaneity 111 ROGER JACKSON Guenther's Saraha: A Detailed Review of Ecstatic Spontaneity Herbert Guenther. Ecstatic Spontaneity: Saraha's Three Cycles of Doha. Nanzan Studies in Asian Religions 4. Berkeley: Asian Humani ties Press, 1993. xvi + 241 pages. Saraha and His Scholars Saraha is one of the great figures in the history of Indian Mahayana Buddhism. As one of the earliest and certainly the most important of the eighty-four eccentric yogis known as the "great adepts" (mahasiddhas), he is as seminal and radical a figure in the tantric tradition as Nagarjuna is in the tradition of sutra-based Mahayana philosophy.l His corpus of what might (with a nod to Blake) be called "songs of experience," in such forms as the doha, caryagiti and vajragiti, profoundly influenced generations of Indian, and then Tibetan, tantric practitioners and poets, above all those who concerned themselves with experience of Maha- mudra, the "Great Seal," or "Great Symbol," about which Saraha wrote so much. -

The Afghanistan-China Belt and Road Initiative

The Afghanistan-China Belt and Road Initiative By Chris Devonshire-Ellis Region: Asia Global Research, August 22, 2021 Theme: Global Economy, Intelligence Silk Road Briefing 18 August 2021 In-depth Report: AFGHANISTAN All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the “Translate Website” drop down menu on the top banner of our home page (Desktop version). Visit and follow us on Instagram at @crg_globalresearch. *** Potential routes exist along the Wakhan Corridor and via Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, but it is Pakistani access to Kabul that looks the better option – as long as the Taliban can provide stability, develop Afghan society, and refrain from regional aggression. International media has focused on Afghanistan these past few days and rightly so as the appalling situation left behind continues its descent into utter chaos. Little mentioned however has been the possibility of restructuring Afghanistan’s supply and trade chains after twenty years of war. While the Russians will largely provide security in the region, China will provide the financing and help build the infrastructure and encourage industrialization and trade in return for peace and security. People tend not to fight when they are in the process of transforming their lives for the better, and Beijing understands this, although much of the social problems are the Taliban’s responsibility to solve. There are several options for China to instigate trade routes with Afghanistan. In this article I discuss the Wakhan Corridor, the finger of Afghanistan that reaches east to the Chinese border, existing trade routes via Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, and the potential to further develop the Karakorum Highway route through the Khunjerab Pass and ultimately via Peshawar to Kabul. -

VT Module6 Lineage Text Major Schools of Tibetan Buddhism

THE MAJOR SCHOOLS OF TIBETAN BUDDHISM By Pema Khandro A BIRD’S EYE VIEW 1. NYINGMA LINEAGE a. Pema Khandro’s lineage. Literally means: ancient school or old school. Nyingmapas rely on the old tantras or the original interpretation of Tantra as it was given from Padmasambhava. b. Founded in 8th century by Padmasambhava, an Indian Yogi who synthesized the teachings of the Indian MahaSiddhas, the Buddhist Tantras, and Dzogchen. He gave this teaching (known as Vajrayana) in Tibet. c. Systemizes Buddhist philosophy and practice into 9 Yanas. The Inner Tantras (what Pema Khandro Rinpoche teaches primarily) are the last three. d. It is not a centralized hierarchy like the Sarma (new translation schools), which have a figure head similar to the Pope. Instead, the Nyingma tradition is de-centralized, with every Lama is the head of their own sangha. There are many different lineages within the Nyingma. e. A major characteristic of the Nyingma tradition is the emphasis in the Tibetan Yogi tradition – the Ngakpa tradition. However, once the Sarma translations set the tone for monasticism in Tibet, the Nyingmas also developed a monastic and institutionalized segment of the tradition. But many Nyingmas are Ngakpas or non-monastic practitioners. f. A major characteristic of the Nyingma tradition is that it is characterized by treasure revelations (gterma). These are visionary revelations of updated communications of the Vajrayana teachings. Ultimately treasure revelations are the same dharma principles but spoken in new ways, at new times and new places to new people. Because of these each treasure tradition is unique, this is the major reason behind the diversity within the Nyingma. -

(And Tantric?) Approaches of the Rim Gyis 'Jug

The Sudden and Gradual Sū tric (and Tantric?) Approaches of the RiM GYis ’jUG Pa’i bsGOM DON aND CiG car ’jUG Pa rNaM Par Mi rTOG Pa’i bsGOM DON JOEL GRUbER According to the dates provided by the Great History of the Rdzogs chen snying thig (Rdzogs pa chen po snying thig gyi lo rgyus chen mo; hereafter Great History), the renowned saint named Vimalamitra was born in India around the latter half of the fifth century. We are told that he spent a majority of his early years studying Buddhism with some of the most esteemed Indian scholars of his generation, until his studies were interrupted by a visit from the bodhisattva Vajrasattva, who encour- aged Vimalamitra to cease practicing exoteric teachings in order to pur- sue a tantric education in China. After two decades of training with the elusive Śrī Siṃha in China, Vimalamitra returned to his homeland to meditate in India’s sacred charnel grounds. Over two hundred years later, word of Vimalamitra’s tantric proficiency reached the Tibetan king, Khri Srong lde brtsan (Trisong Detsen), who invited the Indian saint to assist with the dissemination of Buddhism throughout the Land of Snows. Though Vimalamitra was purportedly three hundred years of age when he journeyed across the Himalayas, his yogic powers were far from diminished. Shortly after departing India, rumors spread to the Tibetan court that Vimalamitra was a necromantic sorcerer rather than a Buddhist saint. Upon his arrival, Tibetan ministers questioned Vimalamitra’s saintly credentials, prompting the tantric master to disintegrate Tibet’s prized statue of Vairocana through the power of a single prostration. -

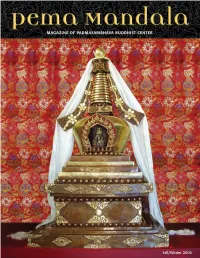

5 Pema Mandala Fall 06 11/21/06 12:02 PM Page 1

5 Pema Mandala Fall 06 11/21/06 12:02 PM Page 1 Fall/Winter 2006 5 Pema Mandala Fall 06 11/21/06 12:03 PM Page 2 Volume 5, Fall/Winter 2006 features A Publication of 3 Letter from the Venerable Khenpos Padmasambhava Buddhist Center Nyingma Lineage of Tibetan Buddhism 4 New Home for Ancient Treasures A long-awaited reliquary stupa is now at home at Founding Directors Ven. Khenchen Palden Sherab Rinpoche Padma Samye Ling, with precious relics inside. Ven. Khenpo Tsewang Dongyal Rinpoche 8 Starting to Practice Dream Yoga Rita Frizzell, Editor/Art Director Ani Lorraine, Contributing Editor More than merely resting, we can use the time we Beth Gongde, Copy Editor spend sleeping to truly benefit ourselves and others. Ann Helm, Teachings Editor Michael Nott, Advertising Director 13 Found in Translation Debra Jean Lambert, Administrative Assistant A student relates how she first met the Khenpos and Pema Mandala Office her experience translating Khenchen’s teachings on For subscriptions, change of address or Mipham Rinpoche. editorial submissions, please contact: Pema Mandala Magazine 1716A Linden Avenue 15 Ten Aspirations of a Bodhisattva Nashville, TN 37212 Translated for the 2006 Dzogchen Intensive. (615) 463-2374 • [email protected] 16 PBC Schedule for Fall 2006 / Winter 2007 Pema Mandala welcomes all contributions submitted for consideration. All accepted submissions will be edited appropriately 18 Namo Buddhaya, Namo Dharmaya, for publication in a magazine represent- Nama Sanghaya ing the Padmasambhava Buddhist Center. Please send submissions to the above A student reflects on a photograph and finds that it address. The deadline for the next issue is evokes more symbols than meet the eye. -

The Prayer, the Priest and the Tsenpo: an Early Buddhist Narrative from Dunhuang

JIABS Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies Volume 30 Number 1–2 2007 (2009) The Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies (ISSN 0193-600XX) is the organ of the International Association of Buddhist Studies, Inc. As a peer-reviewed journal, it welcomes scholarly contributions pertaining to all facets of Buddhist EDITORIAL BOARD Studies. JIABS is published twice yearly. KELLNER Birgit Manuscripts should preferably be sub- KRASSER Helmut mitted as e-mail attachments to: [email protected] as one single fi le, Joint Editors complete with footnotes and references, in two diff erent formats: in PDF-format, BUSWELL Robert and in Rich-Text-Format (RTF) or Open- Document-Format (created e.g. by Open CHEN Jinhua Offi ce). COLLINS Steven Address books for review to: COX Collet JIABS Editors, Institut für Kultur- und GÓMEZ Luis O. Geistesgeschichte Asiens, Prinz-Eugen- HARRISON Paul Strasse 8-10, A-1040 Wien, AUSTRIA VON HINÜBER Oskar Address subscription orders and dues, changes of address, and business corre- JACKSON Roger spondence (including advertising orders) JAINI Padmanabh S. to: KATSURA Shōryū Dr Jérôme Ducor, IABS Treasurer Dept of Oriental Languages and Cultures KUO Li-ying Anthropole LOPEZ, Jr. Donald S. University of Lausanne MACDONALD Alexander CH-1015 Lausanne, Switzerland email: [email protected] SCHERRER-SCHAUB Cristina Web: http://www.iabsinfo.net SEYFORT RUEGG David Fax: +41 21 692 29 35 SHARF Robert Subscriptions to JIABS are USD 40 per STEINKELLNER Ernst year for individuals and USD 70 per year for libraries and other institutions. For TILLEMANS Tom informations on membership in IABS, see back cover. -

Wisdom Buddha Dorje Shugden Blog Al Jazeera Top Story

Wisdom Buddha Dorje Shugden Blog: Al Jazeera Top Story -- Revisits Court Case against the Dalai Lama 1/15/09 12:32 PM Wisdom Buddha Dorje Shugden Blog The official blog of the Wisdom Buddha Dorje Shugden Website, providing the latest news, videos, and updates on the Dorje Shugden controversy. WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 14, 2009 Subscribe Al Jazeera Top Story -- Revisits Court Case against Posts the Dalai Lama Comments Al Jazeera’s People and Power has named ‘The Dalai Lama: The Devil Within’ one of their top two stories of 2008. As a result, Al Jazeera is now Protector of Je featuring it again. Tsongkhapa's Tradition The reporter has added at the end of the updated report: "The case against the Dalai Lama is still with the courts. We hope to bring you an update later in the year." As the lawyer for the persecuted Shugden practitioners, Shree Sanjay Jain, explains: "It is certainly a case of religious discrimination in the sense that if within your sect of religion you say that this particular Deity ought not to be worshipped, and those persons who are willing to worship him you are trying to excommunicate them from the main stream of Buddhism, then it is a discrimination of worst kind." Al Jazeera adds: "No matter what the outcome of the court case, in a country Click on picture for Wisdom Buddha Dorje Shugden where millions of idols are worshipped, attempting to ban the Website Deity is an uphill battle. One in which many Buddhist monks have lost their faith in the spirit of the Dalai Lama." Search For a full transcript, see Al Jazeera News Documentary, October 2008. -

Chinese Censors Crack Down on Tweets

ABCDE Democracy Dies in Darkness SUNDAY, JANUARY 6, 2019 Chinese censors crack down on tweets Police head to doorsteps in interviews to The Washington Post that to pressure Twitter users authorities are sharply escalating the Twit- to delete messages ter crackdown. It suggests a wave of new and more aggressive tactics by state cen- by Gerry Shih sors and cyber-watchers trying to control the Internet. HONG KONG — The 50-year-old software Twitter is banned in China — as are engineer was tapping away at his computer other non-Chinese sites such as Facebook, in November when state security officials YouTube and Instagram. But they are filed into his office on mainland China. accessed by workarounds such as a virtual They had an unusual — and nonnego- private network, or VPN, which is software tiable — request. that bypasses state-imposed firewalls. Delete these tweets, they said. While Chinese authorities block almost The agents handed over a printout of all foreign social media sites, they rarely 60 posts the engineer had fired off to his have taken direct action against citizens 48,000 followers. The topics included U.S.- who use them, preferring instead to quietly China trade relations and the plight of monitor what the Chinese are saying. underground Christians in his coastal prov- But recently, Internet monitors and ince in southeast China. activists have tallied at least 40 cases of When the engineer did not comply Chinese authorities pressuring users to after 24 hours, he discovered that someone delete tweets through a decidedly low-tech had hacked into his Twitter account and method: showing up at their doorsteps. -

PDF Generated By

OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – FIRSTPROOFS, Mon Dec 07 2015, NEWGEN 3 Vajrayāna Traditions in Nepal Todd Lewis and Naresh Man Bajracarya Introduction The existence of tantric traditions in the Kathmandu Valley dates back at least a thousand years and has been integral to the Hindu– Buddhist civi- lization of the Newars, its indigenous people, until the present day. This chapter introduces what is known about the history of the tantric Buddhist tradition there, then presents an analysis of its development in the pre- modern era during the Malla period (1200–1768 ce), and then charts changes under Shah rule (1769–2007). We then sketch Newar Vajrayāna Buddhism’s current characteristics, its leading tantric masters,1 and efforts in recent decades to revitalize it among Newar practitioners. This portrait,2 especially its history of Newar Buddhism, cannot yet be more than tentative in many places, since scholarship has not even adequately documented the textual and epigraphic sources, much less analyzed them systematically.3 The epigraphic record includes over a thousand inscrip- tions, the earliest dating back to 464 ce, tens of thousands of manuscripts, the earliest dating back to 998 ce, as well as the myriad cultural traditions related to them, from art and architecture, to music and ritual. The religious traditions still practiced by the Newars of the Kathmandu Valley represent a unique, continuing survival of Indic religions, including Mahāyāna- Vajrayāna forms of Buddhism (Lienhard 1984; Gellner 1992). Rivaling in historical importance the Sanskrit texts in Nepal’s libraries that informed the Western “discovery” of Buddhism in the nineteenth century (Hodgson 1868; Levi 1905– 1908; Locke 1980, 1985), Newar Vajrayāna acprof-9780199763689.indd 872C28B.1F1 Master Template has been finalized on 19- 02- 2015 12/7/2015 6:28:54 PM OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – FIRSTPROOFS, Mon Dec 07 2015, NEWGEN 88 TanTric TradiTions in Transmission and TranslaTion tradition in the Kathmandu Valley preserves a rich legacy of vernacular texts, rituals, and institutions. -

THE SECURITISATION of TIBETAN BUDDHISM in COMMUNIST CHINA Abstract

ПОЛИТИКОЛОГИЈА РЕЛИГИЈЕ бр. 2/2012 год VI • POLITICS AND RELIGION • POLITOLOGIE DES RELIGIONS • Nº 2/2012 Vol. VI ___________________________________________________________________________ Tsering Topgyal 1 Прегледни рад Royal Holloway University of London UDK: 243.4:323(510)”1949/...” United Kingdom THE SECURITISATION OF TIBETAN BUDDHISM IN COMMUNIST CHINA Abstract This article examines the troubled relationship between Tibetan Buddhism and the Chinese state since 1949. In the history of this relationship, a cyclical pattern of Chinese attempts, both violently assimilative and subtly corrosive, to control Tibetan Buddhism and a multifaceted Tibetan resistance to defend their religious heritage, will be revealed. This article will develop a security-based logic for that cyclical dynamic. For these purposes, a two-level analytical framework will be applied. First, the framework of the insecurity dilemma will be used to draw the broad outlines of the historical cycles of repression and resistance. However, the insecurity dilemma does not look inside the concept of security and it is not helpful to establish how Tibetan Buddhism became a security issue in the first place and continues to retain that status. The theory of securitisation is best suited to perform this analytical task. As such, the cycles of Chinese repression and Tibetan resistance fundamentally originate from the incessant securitisation of Tibetan Buddhism by the Chinese state and its apparatchiks. The paper also considers the why, how, and who of this securitisation, setting the stage for a future research project taking up the analytical effort to study the why, how and who of a potential desecuritisation of all things Tibetan, including Tibetan Buddhism, and its benefits for resolving the protracted Sino- Tibetan conflict.