Copyright by Patrick Warren Eubanks 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Propaganda, «Fake News» Y La Nueva Geopolítica De La Información

Documento de trabajo 8/2019 14 de mayo de 2019 La sociedad de la desinformación: propaganda, «fake news» y la nueva geopolítica de la información Ángel Badillo La sociedad de la desinformación: propaganda, «fake news» y la nueva geopolítica de la información Documento de trabajo 8/2019 - 14 de mayo de 2019 - Real Instituto Elcano La sociedad de la desinformación: propaganda, «fake news» y la nueva geopolítica de la información Ángel Badillo | Investigador principal, Real Instituto Elcano | @angelbadillo Índice Tema ............................................................................................................................ 3 Resumen ...................................................................................................................... 3 Introducción .................................................................................................................. 3 Información y desinformación en la esfera pública ........................................................ 4 Propaganda: construyendo el consenso social .......................................................... 5 Los efectos sociales de los medios ........................................................................... 6 La revolución no será televisada: medios y política ................................................... 7 La sociedad de la (des)información ......................................................................... 12 Un modelo integral de desinformación ....................................................................... -

2018 FLMW Annual Report

First Look Media Works Annual Report 2018 Contents Note From the CEO 3 The Intercept 5 Field of Vision 11 Press Freedom Defense Fund 17 Financials 20 “Our nation is stronger when we protect the rights of individuals to speak their minds, associate with whomever they please, and criticize their government and others in power.” — Pierre Omidyar, founder A Note From the CEO Welcome to First Look. First Look Media Works is a one-of-a-kind media organization that was built for the moment we live in. Amid widespread distress and despair about the fate of our democracy and our world, First Look is about transparency and daylight, truth and responsibility, individual liberty and public good. First Look exposes injustice, shapes culture with voices that reflect who we really are, and defends those who can’t defend themselves. First Look is home to The Intercept, dedicated to fearless investigative journalism; Field of Vision, the filmmaker-driven documentary unit; and the Press Freedom Defense Fund, supporting journalists and whistleblowers facing legal threats. We live, breathe, and defend the First Amendment, and our programs empower the most ambitious voices in journalism and cinematic storytelling. I invite you to learn more about each of them here. All of us pursuing this work — our crusading investigative journalists, some famous and all remarkable; visionary and innovative filmmakers, many of them young and of color; indefatigable legal experts defending press freedom; and dozens of behind-the-scenes co-workers — believe the impact of First Look is vital. As CEO, I am humbled by the courage and passion of the team. -

United States Court of Appeals for the SECOND CIRCUIT

Case 14-2985, Document 88, 12/15/2014, 1393895, Page1 of 64 14-2985-cv IN THE United States Court of Appeals FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT In the Matter ofd a Warrant to Search a Certain E-mail Account Controlled and Maintained by Microsoft Corporation, MICROSOFT CORPORATION, Appellant, —v.— UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Appellee. ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE MEDIA ORGANIZATIONS IN SUPPORT OF APPELLANT LAURA R. HANDMAN ALISON SCHARY DAVIS WRIGHT TREMAINE LLP 1919 Pennsylvania Avenue NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20006 (202) 973-4200 Attorneys for Amici Curiae Media Organizations Case 14-2985, Document 88, 12/15/2014, 1393895, Page2 of 64 OF COUNSEL Indira Satyendra David Vigilante John W. Zucker CABLE NEWS NETWORK , INC . ABC, INC . One CNN Center 77 West 66th Street, 15th Floor Atlanta, GA 30303 New York, NY 10036 Counsel for Cable News Network, Counsel for ABC, Inc. Inc. Richard A. Bernstein Andrew Goldberg SABIN , BERMANT & GOULD LLP THE DAILY BEAST One World Trade Center 555 West 18th Street 44th Floor New York, New York 10011 New York, NY 10007 Counsel for The Daily Beast Counsel for Advance Publications, Company LLC Inc. Matthew Leish Kevin M. Goldberg Cyna Alderman FLETCHER HEALD & HILDRETH NEW YORK DAILY NEWS 1300 North 17th Street, 11th Floor 4 New York Plaza Arlington, VA 22209 New York, NY 10004 Counsel for the American Counsel for Daily News, L.P. Society of News Editors and the Association of Alternative David M. Giles Newsmedia THE E.W. SCRIPPS COMPANY 312 Walnut St., Suite 2800 Scott Searl Cincinnati, OH 45202 BH MEDIA GROUP Counsel for The E.W. -

Per Questa Pagina Non Estrarre Pdf Per Questa Pagina Non Estrarre Pdf

PER QUESTA PAGINA NON ESTRARRE PDF PER QUESTA PAGINA NON ESTRARRE PDF 6 68 Editorʼs Letter A Diva on Fifth Avenue photography Michael Avedon 8 Bulgari Goes to New York. 78 Silvia Schwarzer Stars on Broadway Andrew Cotto photography Gianuzzi & Marino Lauren Remington Platt 92 16 How Many Parties! Beautiful in Bulgari photography Alexander Beckoven 24 110 Empire State of Style Wish upon a Star illustrations Emiliano Ponzi illustrations Federico Babina 32 120 Headin’ New York City. New Opening in Fifth Avenue We Love America 124 American Energy Glory on the Fifth Glory from the Streets From Rome to New York 128 photography Lino Baldissin Events 60 132 One Night in New York Product Summary LIFE IN BVLGARI edited by MEMORIA PUBLISHING GROUP in collaboration with BVLGARI EDITORIAL AND CREATIVE DIRECTION Carlo Mazzoni ART DIRECTION Giulio Vescovi/itsallgood TEXTS Cesare Cunaccia GRAPHIC DESIGN Susanna Mollica MANAGING DIRECTION Marta Mazzacano PRODUCER Marco Tinari ILLUSTRATIONS Lulu* SPECIAL THANKS Costanza Maglio TRANSLATIONS Tdr Translation Company photography Lino Baldissin We are now approaching the end of 2017 and we are prouder this year than ever before to have celebrated the joyful and ex- uberant Bulgari Larger-than-Life lifestyle in all our creations and celebrations. In June, Bulgari chose to celebrate the joy of Italian art de vivre with a spectacular collection of High Jewelry called Festa. More than 100 masterpieces of jewelry and high-end watches were specially created for this new collection, which pays a tribute to the sense of pure happiness of Italian festivals. The collection was presented in Venice, the hometown of two world famous festivals, and is pure color, joy and unexpected creativity through child- hood memories, princesses’ balls and Italian festivals. -

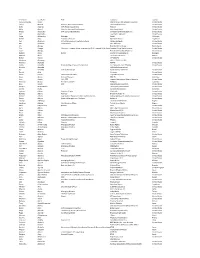

First Name Last Name Title Company Country Anouk Florencia Aaron Warner Bros

First Name Last Name Title Company Country Anouk Florencia Aaron Warner Bros. International Television United States Carlos Abascal Director, Ole Communications Ole Communications United States Kelly Abcarian SVP, Product Leadership Nielsen United States Mike Abend Director, Business Development New Form Digital United States Friday Abernethy SVP, Content Distribution Univision Communications Inc United States Jack Abernethy Twentieth Television United States Salua Abisambra Manager Salabi Colombia Rafael Aboy Account Executive Newsline Report Argentina Cori Abraham SVP of Development and International Oxygen Network United States Mo Abraham Camera Man VIP Television United States Cris Abrego Endemol Shine Group Netherlands Cris Abrego Chairman, Endemol Shine Americas and CEO, Endemol Shine North EndemolAmerica Shine North America United States Steve Abrego Endemol Shine North America United States Patrícia Abreu Dirctor Upstar Comunicações SA Portugal Manuel Abud TV Azteca SAB de CV Mexico Rafael Abudo VIP 2000 TV United States Abraham Aburman LIVE IT PRODUCTIONS Francine Acevedo NATPE United States Hulda Acevedo Programming Acquisitions Executive A+E Networks Latin America United States Kristine Acevedo All3Media International Ric Acevedo Executive Producer North Atlantic Media LLC United States Ronald Acha Univision United States David Acosta Senior Vice President City National Bank United States Jorge Acosta General Manager NTC TV Colombia Juan Acosta EVP, COO Viacom International Media Networks United States Mauricio Acosta President and CEO MAZDOC Colombia Raul Acosta CEO Global Media Federation United States Viviana Acosta-Rubio Telemundo Internacional United States Camilo Acuña Caracol Internacional Colombia Andrea Adams Director of Sales FilmTrack United States Barbara Adams Founder Broken To Reign TV United States Robin C. Adams Executive In Charge of Content and Production Endavo Media and Communications, Inc. -

Eb Greenwald Quark

Liberal Journalist Resigns Due to Censorship This article is from the Edifying the Body section of the Church of God’s Big Sandy website, churchofgodbigsandy.com. It was posted for the weekend of Oct. 31, 2020. A version of the article was posted at greenwald.com on Oct. 29. By Glenn Greenwald NEW YORK, N.Y.—Today I sent my intention to resign from The Intercept, the news outlet I cofounded in 2013 with Jeremy Scahill and Laura Poitras, as well as from its parent company, First Look Media. Wanted to censor my article The final, precipitating cause is that The Intercept’s editors, in violation of my contractual right of editorial freedom, censored an article I wrote this week, refusing to publish it unless I remove all sections critical of Democratic pres- idential candidate Joe Biden, the candidate vehemently supported by all New York–based Intercept editors involved in this effort at suppression. The censored article, based on recently revealed emails and witness testimo- ny, raised critical questions about Biden’s conduct. Not content to simply pre- vent publication of this article at the media outlet I cofounded, these Intercept editors also demanded that I refrain from exercising a separate contractual right to publish this article with any other publication. Don’t mind disagreement I had no objection to their disagreement with my views of what this Biden evidence shows: As a last-ditch attempt to avoid being censored, I encour- aged them to air their disagreements with me by writing their own articles that critique my perspectives and letting readers decide who is right, the way any confident and healthy media outlet would. -

The Global Expansion of Digital-Born News Media

DIGITAL NEWS PROJECT 2017 The Global Expansion of Digital-Born News Media Tom Nicholls, Nabeelah Shabbir, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Contents About the Authors 5 Acknowledgements 6 Executive Summary 7 1. Introduction 9 2. Business Models and the Pursuit of International Scale 14 3. Distribution Strategies and the Embrace of Platforms 16 4. Global Expansion and Brand Licensing 18 5. Editorial Strategy and Brand Identity across Countries 21 6. The Challenges of Working Globally 24 6. Conclusions 27 List of Interviewees 29 References 30 THE GLOBAL EXPANSION OF DIGITAL-BORN NEWS MEDIA About the Authors Tom Nicholls is a Research Fellow at the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism at the University of Oxford. Main research interests include the dynamics of digital news and developing new methodological approaches to studying online activities using digital trace data. Most recently he has been using large-scale quantitative methods to analyse the structure, scope, and interconnectedness of government activity online, the effectiveness of electronic public service delivery, and the Internet’s implications for public management. He has published in various journals including Social Science Computer Review and the Journal of Information Policy. Nabeelah Shabbir is a freelance journalist, formerly of the Guardian, who specialises in pan- European journalism, global environmental coverage, and digital storytelling. Rasmus Kleis Nielsen is Director of Research at the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, Professor of Political Communication at the University of Oxford, and serves as editor-in-chief of the International Journal of Press/Politics. His work focuses on changes in the news media, on political communication, and the role of digital technologies in both. -

Pivot to What? the Metajournalistic Discourse Surrounding Facebook‟S “Push to Video” Trevor Hook December 2020 Dr. Ryan Th

PIVOT TO WHAT? THE METAJOURNALISTIC DISCOURSE SURROUNDING FACEBOOK‟S “PUSH TO VIDEO” TREVOR HOOK DECEMBER 2020 DR. RYAN THOMAS PIVOT TO WHAT? THE METAJOURNALISTIC DISCOURSE SURROUNDING FACEBOOK‟S “PUSH TO VIDEO” Dr. Ryan Thomas Prof. Ryan Famuliner Acknowledgements I would like to thank my chair Dr. Ryan Thomas and committee member Ryan Famuliner for their invaluable assistance in the completion of this master‟s project. Their help was vital in completing a project which has been undertaken in, as said many times elsewhere, an unprecendented time. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1 Literature Review .......................................................................................................... 4 Facebook, Algorithms, and Journalism ......................................................................... 4 Facebook as an Irregular Gatekeeper ............................................................................ 6 The Philosophical Fault Lines between Facebook and Journalism ................................ 7 Facebook‟s Impact in the Practice of Journalism ........................................................ 11 Metajournalistic Discourse ......................................................................................... 13 Research Question...................................................................................................... 14 Method ........................................................................................................................ -

Media Relationships to Identify Topics of Interest and Create a Plan to Infiltrate

The art & science of earned-first storytelling 300 hours of video Average of 6,000 uploaded to YouTube tweets per second every minute 95 million Instagram 4 million Facebook photos and videos likes per second posted each day 3 Filter bubbles result from personalized searches when a website algorithm selectively guesses what information a user would like to see based on information about the user (such as location, past click behavior and search history). The implication is that brands need to generate targeted, quality coverage that can pierce the filter bubbles around their audience. Forget the 24/7 news cycle. Welcome to the “garbage-fire news cycle” – where one tweet lights the world on fire. The result is a real-time stream of flashpoints that are: • Instant • Heated • Flooded with content • Fueled by Google-able context • Often ill-informed or steered by opinion . 9 . More people get news from their phones than ever — 72% of American adults in 2016 versus 54% three years ago. More than half (51%) of consumers say they use social media as a source of news each week. ROUGHLY Remembered the Less than path/platform half recalled where they found name of the the news story news outlet Q10b/cii_2016. Thinking about when you have used social media/aggregators for news, typically how often do you notice the news brand that has supplied the content? Notice = those who always or mostly notice the brand “Facebook is essentially running a payola scam where you have to pay them if you want your own fans to see your content. -

AFS Year 7 Slate MASTER

AFS YEAR 7 FILM SLATE "1 AFS 2018-2019 FILM THEMES *Please note that this thematic breakdown includes documentary features, documentary shorts, animated shorts and episodic documentaries American Arts & Culture Entrepreneurism Chasing Trane! Blood, Sweat & Beer! Gentlemen of Vision! Chef Flynn! Honky Tonk Heaven: Legend of the Dealt! Broken Spoke! Ella Brennan: Commanding the Table! Jake Shimabukuro: Life on Four Strings Good Fortune! More Art Upstairs! Knife Skills! Moving Stories! New Chefs on the Block! Obit! One Hundred Thousand Beating Hearts! Restless Creature: Wendy Whelan! Human Rights Score: A Film Music Documentary! STEP! A Shot in the Dark! All-American Family! Disability Rights Bending the Arc! A Shot in the Dark! Cradle! All-American Family! Edith + Eddie! Cradle! I Am Jane Doe! Dealt! The Prosecutors! I’ll Push You! Unrest! Pick of the Litter! LGBTQI Reengineering Sam! Served Like a Girl! In A Heartbeat! Unrest! The S Word: Opening the Conversation Stumped# About Suicide! Stumped! "2 Mental Health Awareness Sports Cradle! A Shot in the Dark! Served Like a Girl! All-American Family! The S Word: Opening the Conversation Baltimore Boys! About Suicide! Born to Lead: The Sal Aunese Story! The Work! Boston: The Documentary! Unrest! Down The Fence! We Breathe Again! Run Mama Run! Skid Row Marathon! The Natural World and Space Take Every Wave: The Life of Laird A Plastic Ocean! Hamilton Above and Beyond: NASA’s Journey to STEM Tomorrow! Frans Lanting: The Evolution of Life! Bombshell: The Hedy Lamarr Story! Mosquito! Dream Big: -

Citizenfour Discussion Guide

www.influencefilmclub.com Citizenfour Discussion Guide Director: Laura Poitras Year: 2015 Time: 114 min You might know this director from: The Oath (2010) My Country, My Country (2006) Flag Wars (2003) FILM SUMMARY Director Laura Poitras was in the middle of her third documentary on post-9/11 America when she received an email from “Citizenfour,” an individual claiming to possess insider information on the wide-scale surveillance schemes of the U.S. government. Rather than brushing the message off as bogus, she pursued this mysterious mailer, embroiling herself in one of the greatest global shockwaves of this millennium thus far. Teaming up with journalist Glenn Greenwald of “The Guardian,” Poitras began her journey. The two travel to Hong Kong, where they meet “Citizenfour,” an infrastructure analyst named Edward Snowden working inside the National Security Agency. Joined by fellow Guardian colleague Ewen MacAskill, the four set up camp in Snowden’s hotel room, where over the course of the following eight days he reveals a shocking protocol in effect that will uproot the way citizens across the world view their leaders in the days to come. Snowden does not wish to remain anonymous, and yet he insists “I’m not the story.” In his mind the issues of liberty, justice, freedom, and democracy are at stake, and who he is has very little bearing on the intense implications of the mass surveillance in effect worldwide. Snowden reminds us, “It’s not science fiction. This is happening right now,” and at times the extent of information is just too massive to grasp, especially for the journalists involved. -

Media Moments 2019

MEDIA MOMENTS 2019 Sponsored by Written by MEDIA MOMENTS 2019 I CONTENTS III Introduction from What’s New in Publishing IV Sovrn: Helping publishers thrive V Foreword from the writers Media Moments 2019 1 M&A Mergers and acquisitions are shaping the media landscape of the future 5 READER REVENUE Publishers are joining the race for reader revenues, but there’s no silver bullet 9 DATA & ADVERTISING First-party data empowers publishers to experiment with personalisation and better ads 13 TRUST Publishers begin the hard climb to earn back widespread public trust 17 PRINT Print publishing remains relevant but continues its search for a long-term rationale 21 MULTIMEDIA Welcoming the calm after the storm in multimedia investment from publishers 25 PLATFORM Platforms offer olive branches with subscription initiatives and news payments to tempt publishers back 29 OPPORTUNITIES FOR 2020 Beyond news: new opportunities for publishers to connect with audiences 33 APPENDIX MEDIA MOMENTS 2019 II INTRODUCTION as 2019 the year publishers finally got their mojo back? Jeremy Walters It would seem so – M&As are on a tear, digital subs @wnip Wshow no signs of hitting ‘paywall fatigue’, and new reve- nue channels are emerging with potent force. As if to illustrate the point, BuzzFeed’s CEO Jonah Peretti re- marked at SXSW that the company generated over $100 million in revenue last year “from business lines that didn’t even exist in 2017.” Peretti added that he expects to see a similar revenue pattern in 2019. But perhaps the biggest change is that publishers are looking after their own interests first.