Glenn Greenwald NO PLACE to HIDE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Propaganda, «Fake News» Y La Nueva Geopolítica De La Información

Documento de trabajo 8/2019 14 de mayo de 2019 La sociedad de la desinformación: propaganda, «fake news» y la nueva geopolítica de la información Ángel Badillo La sociedad de la desinformación: propaganda, «fake news» y la nueva geopolítica de la información Documento de trabajo 8/2019 - 14 de mayo de 2019 - Real Instituto Elcano La sociedad de la desinformación: propaganda, «fake news» y la nueva geopolítica de la información Ángel Badillo | Investigador principal, Real Instituto Elcano | @angelbadillo Índice Tema ............................................................................................................................ 3 Resumen ...................................................................................................................... 3 Introducción .................................................................................................................. 3 Información y desinformación en la esfera pública ........................................................ 4 Propaganda: construyendo el consenso social .......................................................... 5 Los efectos sociales de los medios ........................................................................... 6 La revolución no será televisada: medios y política ................................................... 7 La sociedad de la (des)información ......................................................................... 12 Un modelo integral de desinformación ....................................................................... -

Copyright by Patrick Warren Eubanks 2019

Copyright by Patrick Warren Eubanks 2019 The Report Committee for Patrick Warren Eubanks Certifies that this is the approved version of the following Report: “There’s No Guidebook for This”: Black Freelancers and Digital Technologies APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: S. Craig Watkins, Supervisor Kathleen McElroy “There’s no Guidebook for This”: Black Freelancers and Digital Technologies by Patrick Warren Eubanks Report Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2019 Abstract “There’s no Guidebook for This”: Black Freelancers and Digital Technologies Patrick Warren Eubanks, MA The University of Texas at Austin, 2019 Supervisor: S. Craig Watkins Freelancing has become increasingly common in a variety of industries due to the continued economic restructuring of post-industrial capitalism. While writing has traditionally been a precarious profession characterized by low pay and intermittent work, once secure forms of employment, such as newspaper work, have experienced a precipitous decline within the past few decades. As the number of writers engaged in standard employment contracts has sharply decreased, an increasing number of individuals must engage in freelance work to earn a living as writers. While all freelance writers face precarity at the hands of digital media outlets due to exploitative and unstable labor and business practices, black freelancers experience distinct forms of precarity, such as a lack of access to professional networks and mentors. This report aims to identify the ways in which digital technologies allow black freelancers to insulate themselves from the risks inherent to the digital media ecosystem, ending with recommendations for education systems, digital media organizations and freelancers seeking to promote equity in digital publishing. -

2018 FLMW Annual Report

First Look Media Works Annual Report 2018 Contents Note From the CEO 3 The Intercept 5 Field of Vision 11 Press Freedom Defense Fund 17 Financials 20 “Our nation is stronger when we protect the rights of individuals to speak their minds, associate with whomever they please, and criticize their government and others in power.” — Pierre Omidyar, founder A Note From the CEO Welcome to First Look. First Look Media Works is a one-of-a-kind media organization that was built for the moment we live in. Amid widespread distress and despair about the fate of our democracy and our world, First Look is about transparency and daylight, truth and responsibility, individual liberty and public good. First Look exposes injustice, shapes culture with voices that reflect who we really are, and defends those who can’t defend themselves. First Look is home to The Intercept, dedicated to fearless investigative journalism; Field of Vision, the filmmaker-driven documentary unit; and the Press Freedom Defense Fund, supporting journalists and whistleblowers facing legal threats. We live, breathe, and defend the First Amendment, and our programs empower the most ambitious voices in journalism and cinematic storytelling. I invite you to learn more about each of them here. All of us pursuing this work — our crusading investigative journalists, some famous and all remarkable; visionary and innovative filmmakers, many of them young and of color; indefatigable legal experts defending press freedom; and dozens of behind-the-scenes co-workers — believe the impact of First Look is vital. As CEO, I am humbled by the courage and passion of the team. -

United States Court of Appeals for the SECOND CIRCUIT

Case 14-2985, Document 88, 12/15/2014, 1393895, Page1 of 64 14-2985-cv IN THE United States Court of Appeals FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT In the Matter ofd a Warrant to Search a Certain E-mail Account Controlled and Maintained by Microsoft Corporation, MICROSOFT CORPORATION, Appellant, —v.— UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Appellee. ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE MEDIA ORGANIZATIONS IN SUPPORT OF APPELLANT LAURA R. HANDMAN ALISON SCHARY DAVIS WRIGHT TREMAINE LLP 1919 Pennsylvania Avenue NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20006 (202) 973-4200 Attorneys for Amici Curiae Media Organizations Case 14-2985, Document 88, 12/15/2014, 1393895, Page2 of 64 OF COUNSEL Indira Satyendra David Vigilante John W. Zucker CABLE NEWS NETWORK , INC . ABC, INC . One CNN Center 77 West 66th Street, 15th Floor Atlanta, GA 30303 New York, NY 10036 Counsel for Cable News Network, Counsel for ABC, Inc. Inc. Richard A. Bernstein Andrew Goldberg SABIN , BERMANT & GOULD LLP THE DAILY BEAST One World Trade Center 555 West 18th Street 44th Floor New York, New York 10011 New York, NY 10007 Counsel for The Daily Beast Counsel for Advance Publications, Company LLC Inc. Matthew Leish Kevin M. Goldberg Cyna Alderman FLETCHER HEALD & HILDRETH NEW YORK DAILY NEWS 1300 North 17th Street, 11th Floor 4 New York Plaza Arlington, VA 22209 New York, NY 10004 Counsel for the American Counsel for Daily News, L.P. Society of News Editors and the Association of Alternative David M. Giles Newsmedia THE E.W. SCRIPPS COMPANY 312 Walnut St., Suite 2800 Scott Searl Cincinnati, OH 45202 BH MEDIA GROUP Counsel for The E.W. -

First Name Last Name Title Company Country Anouk Florencia Aaron Warner Bros

First Name Last Name Title Company Country Anouk Florencia Aaron Warner Bros. International Television United States Carlos Abascal Director, Ole Communications Ole Communications United States Kelly Abcarian SVP, Product Leadership Nielsen United States Mike Abend Director, Business Development New Form Digital United States Friday Abernethy SVP, Content Distribution Univision Communications Inc United States Jack Abernethy Twentieth Television United States Salua Abisambra Manager Salabi Colombia Rafael Aboy Account Executive Newsline Report Argentina Cori Abraham SVP of Development and International Oxygen Network United States Mo Abraham Camera Man VIP Television United States Cris Abrego Endemol Shine Group Netherlands Cris Abrego Chairman, Endemol Shine Americas and CEO, Endemol Shine North EndemolAmerica Shine North America United States Steve Abrego Endemol Shine North America United States Patrícia Abreu Dirctor Upstar Comunicações SA Portugal Manuel Abud TV Azteca SAB de CV Mexico Rafael Abudo VIP 2000 TV United States Abraham Aburman LIVE IT PRODUCTIONS Francine Acevedo NATPE United States Hulda Acevedo Programming Acquisitions Executive A+E Networks Latin America United States Kristine Acevedo All3Media International Ric Acevedo Executive Producer North Atlantic Media LLC United States Ronald Acha Univision United States David Acosta Senior Vice President City National Bank United States Jorge Acosta General Manager NTC TV Colombia Juan Acosta EVP, COO Viacom International Media Networks United States Mauricio Acosta President and CEO MAZDOC Colombia Raul Acosta CEO Global Media Federation United States Viviana Acosta-Rubio Telemundo Internacional United States Camilo Acuña Caracol Internacional Colombia Andrea Adams Director of Sales FilmTrack United States Barbara Adams Founder Broken To Reign TV United States Robin C. Adams Executive In Charge of Content and Production Endavo Media and Communications, Inc. -

Eb Greenwald Quark

Liberal Journalist Resigns Due to Censorship This article is from the Edifying the Body section of the Church of God’s Big Sandy website, churchofgodbigsandy.com. It was posted for the weekend of Oct. 31, 2020. A version of the article was posted at greenwald.com on Oct. 29. By Glenn Greenwald NEW YORK, N.Y.—Today I sent my intention to resign from The Intercept, the news outlet I cofounded in 2013 with Jeremy Scahill and Laura Poitras, as well as from its parent company, First Look Media. Wanted to censor my article The final, precipitating cause is that The Intercept’s editors, in violation of my contractual right of editorial freedom, censored an article I wrote this week, refusing to publish it unless I remove all sections critical of Democratic pres- idential candidate Joe Biden, the candidate vehemently supported by all New York–based Intercept editors involved in this effort at suppression. The censored article, based on recently revealed emails and witness testimo- ny, raised critical questions about Biden’s conduct. Not content to simply pre- vent publication of this article at the media outlet I cofounded, these Intercept editors also demanded that I refrain from exercising a separate contractual right to publish this article with any other publication. Don’t mind disagreement I had no objection to their disagreement with my views of what this Biden evidence shows: As a last-ditch attempt to avoid being censored, I encour- aged them to air their disagreements with me by writing their own articles that critique my perspectives and letting readers decide who is right, the way any confident and healthy media outlet would. -

AFS Year 7 Slate MASTER

AFS YEAR 7 FILM SLATE "1 AFS 2018-2019 FILM THEMES *Please note that this thematic breakdown includes documentary features, documentary shorts, animated shorts and episodic documentaries American Arts & Culture Entrepreneurism Chasing Trane! Blood, Sweat & Beer! Gentlemen of Vision! Chef Flynn! Honky Tonk Heaven: Legend of the Dealt! Broken Spoke! Ella Brennan: Commanding the Table! Jake Shimabukuro: Life on Four Strings Good Fortune! More Art Upstairs! Knife Skills! Moving Stories! New Chefs on the Block! Obit! One Hundred Thousand Beating Hearts! Restless Creature: Wendy Whelan! Human Rights Score: A Film Music Documentary! STEP! A Shot in the Dark! All-American Family! Disability Rights Bending the Arc! A Shot in the Dark! Cradle! All-American Family! Edith + Eddie! Cradle! I Am Jane Doe! Dealt! The Prosecutors! I’ll Push You! Unrest! Pick of the Litter! LGBTQI Reengineering Sam! Served Like a Girl! In A Heartbeat! Unrest! The S Word: Opening the Conversation Stumped# About Suicide! Stumped! "2 Mental Health Awareness Sports Cradle! A Shot in the Dark! Served Like a Girl! All-American Family! The S Word: Opening the Conversation Baltimore Boys! About Suicide! Born to Lead: The Sal Aunese Story! The Work! Boston: The Documentary! Unrest! Down The Fence! We Breathe Again! Run Mama Run! Skid Row Marathon! The Natural World and Space Take Every Wave: The Life of Laird A Plastic Ocean! Hamilton Above and Beyond: NASA’s Journey to STEM Tomorrow! Frans Lanting: The Evolution of Life! Bombshell: The Hedy Lamarr Story! Mosquito! Dream Big: -

Citizenfour Discussion Guide

www.influencefilmclub.com Citizenfour Discussion Guide Director: Laura Poitras Year: 2015 Time: 114 min You might know this director from: The Oath (2010) My Country, My Country (2006) Flag Wars (2003) FILM SUMMARY Director Laura Poitras was in the middle of her third documentary on post-9/11 America when she received an email from “Citizenfour,” an individual claiming to possess insider information on the wide-scale surveillance schemes of the U.S. government. Rather than brushing the message off as bogus, she pursued this mysterious mailer, embroiling herself in one of the greatest global shockwaves of this millennium thus far. Teaming up with journalist Glenn Greenwald of “The Guardian,” Poitras began her journey. The two travel to Hong Kong, where they meet “Citizenfour,” an infrastructure analyst named Edward Snowden working inside the National Security Agency. Joined by fellow Guardian colleague Ewen MacAskill, the four set up camp in Snowden’s hotel room, where over the course of the following eight days he reveals a shocking protocol in effect that will uproot the way citizens across the world view their leaders in the days to come. Snowden does not wish to remain anonymous, and yet he insists “I’m not the story.” In his mind the issues of liberty, justice, freedom, and democracy are at stake, and who he is has very little bearing on the intense implications of the mass surveillance in effect worldwide. Snowden reminds us, “It’s not science fiction. This is happening right now,” and at times the extent of information is just too massive to grasp, especially for the journalists involved. -

U.S. Court of Appeals for the First Circuit Court Decision

Case: 19-1586 Document: 00117681683 Page: 1 Date Filed: 12/15/2020 Entry ID: 6388777 United States Court of Appeals For the First Circuit Nos. 19-1586, 19-1640 PROJECT VERITAS ACTION FUND, Plaintiff, Appellee / Cross-Appellant, v. RACHAEL S. ROLLINS, in her official capacity as District Attorney for Suffolk County, Defendant, Appellant / Cross-Appellee. No. 19-1629 K. ERIC MARTIN & RENÉ PÉREZ, Plaintiffs, Appellees, v. RACHAEL S. ROLLINS, in her official capacity as District Attorney for Suffolk County, Defendant, Appellant, WILLIAM G. GROSS, in his official capacity as Police Commissioner for the City of Boston, Defendant. APPEALS FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF MASSACHUSETTS [Hon. Patti B. Saris, U.S. District Judge] Case: 19-1586 Document: 00117681683 Page: 2 Date Filed: 12/15/2020 Entry ID: 6388777 Before Barron, Circuit Judge, Souter,* Associate Justice, and Selya, Circuit Judge. Eric A. Haskell, Assistant Attorney General of Massachusetts, with whom Maura Healey, Attorney General of Massachusetts, was on brief, for Appellant/Cross-Appellee Rachael S. Rollins. Benjamin T. Barr, with whom Steve Klein and Statecraft PLLC were on brief, for Appellee/Cross-Appellant Project Veritas. Jessie J. Rossman, with whom Matthew R. Segal, American Civil Liberties Union Foundation of Massachusetts, Inc., William D. Dalsen, and Proskauer Rose LLP were on brief, for Appellees K. Eric Martin and René Pérez. Adam Schwartz and Sophia Cope on brief for Electronic Frontier Foundation, amicus curiae. Bruce D. Brown, Katie Townsend, Josh R. Moore, Shannon A. Jankowski, Dan Krockmalnic, David Bralow, Kurt Wimmer, Covington & Burling LLP, Joshua N. Pila, James Cregan, Tonda F. -

Complete Return for FLMINC

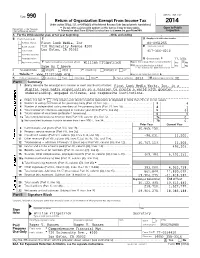

OMB No. 1545-0047 Form 990 Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax 2014 Under section 501(c), 527, or 4947(a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code (except private foundations) G Do not enter social security numbers on this form as it may be made public. Open to Public Department of the Treasury Inspection Internal Revenue Service G Information about Form 990 and its instructions is at www.irs.gov/form990. A For the 2014 calendar year, or tax year beginning , 2014, and ending , B Check if applicable: C D Employer identification number Address change First Look Media, Inc 80-0951255 Name change 720 University Avenue #200 E Telephone number Initial return Los Gatos, CA 95032 917-304-4210 Final return/terminated Amended return G Gross receipts $ 11,505. F H(a) Is this a group return for subordinates? Application pending Name and address of principal officer: William Fitzpatrick Yes X No H(b) Are all subordinates included? Yes No Same As C Above If 'No,' attach a list. (see instructions) I Tax-exempt status X 501(c)(3) 501(c) ( )H (insert no.) 4947(a)(1) or 527 J Website: G www.firstlook.org H(c) Group exemption number G G K Form of organization: X Corporation Trust Association Other L Year of formation: 2013 M State of legal domicile: DE Part I Summary 1 Briefly describe the organization's mission or most significant activities: First Look Media Works, Inc, is a digital news media organization on a mission to create a world with greater understanding, engaged citizens, and responsive institutions. -

No. 1:16-Cv-00025-TDS-JEP

No. 1:16-cv-00025-TDS-JEP IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA PEOPLE FOR THE ETHICAL TREATMENT OF ANIMALS, INC.; CENTER FOR FOOD SAFETY; ANIMAL LEGAL DEFENSE FUND; FARM SANCTUARY; FOOD & WATER WATCH; GOVERNMENT ACCOUNTABILITY PROJECT; FARM FORWARD; and AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR THE PREVENTION OF CRUELTY TO ANIMALS Plaintiffs, v. ROY COOPER, in his official capacity as Attorney General of North Carolina, and CAROL FOLT, in her official capacity as Chancellor of the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, Defendants, And NORTH CAROLINA FARM BUREAU FEDERATION, INC., Intervenor-Defendant. BRIEF AMICI CURIAE OF THE REPORTERS COMMITTEE FOR FREEDOM OF THE PRESS AND 21 OTHER ORGANIZATIONS IN SUPPORT OF PLAINTIFFS’ MOTION FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT Jonathan E. Buchan N.C. Bar No. 8205 Essex Richards, P.A. 1701 South Blvd. Charlotte, NC 28203 Phone: 704-377-4300 Email: [email protected] Counsel for Amici Curiae [Full Counsel Listing in Appendix B] Case 1:16-cv-00025-TDS-JEP Document 106 Filed 09/03/19 Page 1 of 33 DISCLOSURE STATEMENT The Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press is an unincorporated nonprofit association of reporters and editors with no parent corporation and no stock. American Society of News Editors is a private, non-stock corporation that has no parent. The Associated Press Media Editors has no parent corporation and does not issue any stock. Association of Alternative Newsmedia has no parent corporation and does not issue any stock. First Look Media Works, Inc. is a non-profit non-stock corporation organized under the laws of Delaware. -

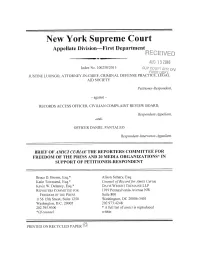

Disciplinary Records for Daniel Pantaleo

TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ................................................................................... iii IDENTITY OF AMICI CURIAE ...............................................................................1 INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT ............................... 3 ARGUMENT .............................................................................................................6 I. CRL 50-a does not impose blanket secrecy on all records relating to police conduct. ............................................................................................................6 A. The scope of CRL 50-a must be narrowly interpreted to provide maximum access to agency records under FOIL. ..................................... 6 B. The trial court’s ruling below properly construes the scope of CRL 50-a in light of FOIL’s mandate of disclosure. ................................................. 7 II. The trial court properly rejected the argument that publication of an article quoting a CCRB investigation demonstrates “a substantial and realistic potential of the requested material for the abusive use.” ..............................12 III. A properly narrow construction of CRL 50-a is necessary to preserve the news media’s ability to gather and report news about law enforcement. .....14 PRINTING SPECIFICATION STATEMENT .......................................................19 APPENDIX A ..........................................................................................................20 APPENDIX