Aldicarb in Drinking-Water

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carbamate Pesticides Aldicarb Aldicarb Sulfoxide Aldicarb Sulfone

Connecticut General Statutes Sec 19a-29a requires the Commissioner of Public Health to annually publish a list setting forth all analytes and matrices for which certification for testing is required. Connecticut ELCP Drinking Water Analytes Revised 05/31/2018 Microbiology Total Coliforms Fecal Coliforms/ E. Coli Carbamate Pesticides Legionella Aldicarb Cryptosporidium Aldicarb Sulfoxide Giardia Aldicarb Sulfone Carbaryl Physicals Carbofuran Turbidity 3-Hydroxycarbofuran pH Methomyl Conductivity Oxamyl (Vydate) Minerals Chlorinated Herbicides Alkalinity, as CaCO3 2,4-D Bromide Dalapon Chloride Dicamba Chlorine, free residual Dinoseb Chlorine, total residual Endothall Fluoride Picloram Hardness, Calcium as Pentachlorophenol CaCO3 Hardness, Total as CaCO3 Silica Chlorinated Pesticides/PCB's Sulfate Aldrin Chlordane (Technical) Nutrients Dieldrin Endrin Ammonia Heptachlor Nitrate Heptachlor Epoxide Nitrite Lindane (gamma-BHC) o-Phosphate Metolachlor Total Phosphorus Methoxychlor PCB's (individual aroclors) Note 1 PCB's (as decachlorobiphenyl) Note 1 Demands Toxaphene TOC Nitrogen-Phosphorus Compounds Alachlor Metals Atrazine Aluminum Butachlor Antimony Diquat Arsenic Glyphosate Barium Metribuzin Beryllium Paraquat Boron Propachlor Cadmium Simazine Calcium Chromium Copper SVOC's Iron Benzo(a)pyrene Lead bis-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate Magnesium bis-(ethylhexyl)adipate Manganese Hexachlorobenzene Mercury Hexachlorocyclopentadiene Molybdenum Nickel Potassium Miscellaneous Organics Selenium Dibromochloropropane (DBCP) Silver Ethylene Dibromide (EDB) -

Florida State Emergency Response Commission

Florida State Emergency Response Commission Sub-Committee on Training (SOT) HAZARDOUS MATERIALS MEDICAL TREATMENT PROTOCOLS Version 3.3 TOXIDROMES Toxidromes are clinical syndromes that the patient presents with. These patterns of signs and symptoms are essential for the successful recognition of chemical exposure. The toxidromes identified in this protocol are chemical exposure based while others such as the opioids are found within general medical protocol. These chemical toxidromes are identified clinically into five syndromes: Irritant Gas Toxidrome Asphyxiant Toxidrome Corrosive Toxidrome Hydrocarbon and Halogenated Hydrocarbons Toxidrome Cholinergic Toxidrome Each can present as a clinical manifestation of the chemical/poisoning involved with some cross-over between toxidromes. This list combines the toxic syndromes found within NFPA 473 (A.5.4.1(2) and traditional syndromes. Toxidrome Correlation to NFPA Standard 473 and Traditional Syndromes Toxidrome NFPA 473 A.5.4.1(2) Hazardous Materials Protocol Correlation Irritant Gas (j) Irritants Bronchospasm OC Pepper spray & lacrimants Asphyxiant (c) Chemical asphyxiants Carbon Monoxide (d) Simple asphyxiants Aniline dyes, Nitriles, Nitrares (h) Blood Agents Cyanide & Hydrogen Sulfide (n) Nitrogen Compounds Closed Space Fires Simple Asphyxants Corrosive (a) Corrosives Hydrofluroic Acid (g) Vesicants Chemical burns to the eye Choramine and Chlorine Hydrocarbon (e) Organic solvents Phenol and (q) Phenolic Compounds Halogenated Hydrocarbons Halogenated Hydrocarbons Cholinergic (b) Pesticides -

Chemical Name Federal P Code CAS Registry Number Acutely

Acutely / Extremely Hazardous Waste List Federal P CAS Registry Acutely / Extremely Chemical Name Code Number Hazardous 4,7-Methano-1H-indene, 1,4,5,6,7,8,8-heptachloro-3a,4,7,7a-tetrahydro- P059 76-44-8 Acutely Hazardous 6,9-Methano-2,4,3-benzodioxathiepin, 6,7,8,9,10,10- hexachloro-1,5,5a,6,9,9a-hexahydro-, 3-oxide P050 115-29-7 Acutely Hazardous Methanimidamide, N,N-dimethyl-N'-[2-methyl-4-[[(methylamino)carbonyl]oxy]phenyl]- P197 17702-57-7 Acutely Hazardous 1-(o-Chlorophenyl)thiourea P026 5344-82-1 Acutely Hazardous 1-(o-Chlorophenyl)thiourea 5344-82-1 Extremely Hazardous 1,1,1-Trichloro-2, -bis(p-methoxyphenyl)ethane Extremely Hazardous 1,1a,2,2,3,3a,4,5,5,5a,5b,6-Dodecachlorooctahydro-1,3,4-metheno-1H-cyclobuta (cd) pentalene, Dechlorane Extremely Hazardous 1,1a,3,3a,4,5,5,5a,5b,6-Decachloro--octahydro-1,2,4-metheno-2H-cyclobuta (cd) pentalen-2- one, chlorecone Extremely Hazardous 1,1-Dimethylhydrazine 57-14-7 Extremely Hazardous 1,2,3,4,10,10-Hexachloro-6,7-epoxy-1,4,4,4a,5,6,7,8,8a-octahydro-1,4-endo-endo-5,8- dimethanonaph-thalene Extremely Hazardous 1,2,3-Propanetriol, trinitrate P081 55-63-0 Acutely Hazardous 1,2,3-Propanetriol, trinitrate 55-63-0 Extremely Hazardous 1,2,4,5,6,7,8,8-Octachloro-4,7-methano-3a,4,7,7a-tetra- hydro- indane Extremely Hazardous 1,2-Benzenediol, 4-[1-hydroxy-2-(methylamino)ethyl]- 51-43-4 Extremely Hazardous 1,2-Benzenediol, 4-[1-hydroxy-2-(methylamino)ethyl]-, P042 51-43-4 Acutely Hazardous 1,2-Dibromo-3-chloropropane 96-12-8 Extremely Hazardous 1,2-Propylenimine P067 75-55-8 Acutely Hazardous 1,2-Propylenimine 75-55-8 Extremely Hazardous 1,3,4,5,6,7,8,8-Octachloro-1,3,3a,4,7,7a-hexahydro-4,7-methanoisobenzofuran Extremely Hazardous 1,3-Dithiolane-2-carboxaldehyde, 2,4-dimethyl-, O- [(methylamino)-carbonyl]oxime 26419-73-8 Extremely Hazardous 1,3-Dithiolane-2-carboxaldehyde, 2,4-dimethyl-, O- [(methylamino)-carbonyl]oxime. -

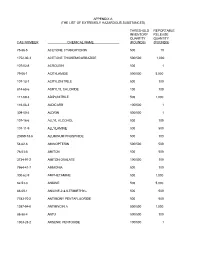

The List of Extremely Hazardous Substances)

APPENDIX A (THE LIST OF EXTREMELY HAZARDOUS SUBSTANCES) THRESHOLD REPORTABLE INVENTORY RELEASE QUANTITY QUANTITY CAS NUMBER CHEMICAL NAME (POUNDS) (POUNDS) 75-86-5 ACETONE CYANOHYDRIN 500 10 1752-30-3 ACETONE THIOSEMICARBAZIDE 500/500 1,000 107-02-8 ACROLEIN 500 1 79-06-1 ACRYLAMIDE 500/500 5,000 107-13-1 ACRYLONITRILE 500 100 814-68-6 ACRYLYL CHLORIDE 100 100 111-69-3 ADIPONITRILE 500 1,000 116-06-3 ALDICARB 100/500 1 309-00-2 ALDRIN 500/500 1 107-18-6 ALLYL ALCOHOL 500 100 107-11-9 ALLYLAMINE 500 500 20859-73-8 ALUMINUM PHOSPHIDE 500 100 54-62-6 AMINOPTERIN 500/500 500 78-53-5 AMITON 500 500 3734-97-2 AMITON OXALATE 100/500 100 7664-41-7 AMMONIA 500 100 300-62-9 AMPHETAMINE 500 1,000 62-53-3 ANILINE 500 5,000 88-05-1 ANILINE,2,4,6-TRIMETHYL- 500 500 7783-70-2 ANTIMONY PENTAFLUORIDE 500 500 1397-94-0 ANTIMYCIN A 500/500 1,000 86-88-4 ANTU 500/500 100 1303-28-2 ARSENIC PENTOXIDE 100/500 1 THRESHOLD REPORTABLE INVENTORY RELEASE QUANTITY QUANTITY CAS NUMBER CHEMICAL NAME (POUNDS) (POUNDS) 1327-53-3 ARSENOUS OXIDE 100/500 1 7784-34-1 ARSENOUS TRICHLORIDE 500 1 7784-42-1 ARSINE 100 100 2642-71-9 AZINPHOS-ETHYL 100/500 100 86-50-0 AZINPHOS-METHYL 10/500 1 98-87-3 BENZAL CHLORIDE 500 5,000 98-16-8 BENZENAMINE, 3-(TRIFLUOROMETHYL)- 500 500 100-14-1 BENZENE, 1-(CHLOROMETHYL)-4-NITRO- 500/500 500 98-05-5 BENZENEARSONIC ACID 10/500 10 3615-21-2 BENZIMIDAZOLE, 4,5-DICHLORO-2-(TRI- 500/500 500 FLUOROMETHYL)- 98-07-7 BENZOTRICHLORIDE 100 10 100-44-7 BENZYL CHLORIDE 500 100 140-29-4 BENZYL CYANIDE 500 500 15271-41-7 BICYCLO[2.2.1]HEPTANE-2-CARBONITRILE,5- -

Malathion Human Health and Ecological Risk Assessment Final Report

SERA TR-052-02-02c Malathion Human Health and Ecological Risk Assessment Final Report Submitted to: Paul Mistretta, COR USDA/Forest Service, Southern Region 1720 Peachtree RD, NW Atlanta, Georgia 30309 USDA Forest Service Contract: AG-3187-C-06-0010 USDA Forest Order Number: AG-43ZP-D-06-0012 SERA Internal Task No. 52-02 Submitted by: Patrick R. Durkin Syracuse Environmental Research Associates, Inc. 5100 Highbridge St., 42C Fayetteville, New York 13066-0950 Fax: (315) 637-0445 E-Mail: [email protected] Home Page: www.sera-inc.com May 12, 2008 Table of Contents Table of Contents............................................................................................................................ ii List of Figures................................................................................................................................. v List of Tables ................................................................................................................................. vi List of Appendices ......................................................................................................................... vi List of Attachments........................................................................................................................ vi ACRONYMS, ABBREVIATIONS, AND SYMBOLS ............................................................... vii COMMON UNIT CONVERSIONS AND ABBREVIATIONS.................................................... x CONVERSION OF SCIENTIFIC NOTATION .......................................................................... -

Table II. EPCRA Section 313 Chemical List for Reporting Year 2017 (Including Toxic Chemical Categories)

Table II. EPCRA Section 313 Chemical List For Reporting Year 2017 (including Toxic Chemical Categories) Individually listed EPCRA Section 313 chemicals with CAS numbers are arranged alphabetically starting on page II-3. Following the alphabetical list, the EPCRA Section 313 chemicals are arranged in CAS number order. Covered chemical categories follow. Note: Chemicals may be added to or deleted from the list. The Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Call Center or the TRI-Listed Chemicals website will provide up-to-date information on the status of these changes. See section B.3.c of the instructions for more information on the de minimis % limits listed below. There are no de minimis levels for PBT chemicals since the de minimis exemption is not available for these chemicals (an asterisk appears where a de minimis limit would otherwise appear in Table II). However, for purposes of the supplier notification requirement only, such limits are provided in Appendix C. Chemical Qualifiers Certain EPCRA Section 313 chemicals listed in Table II have parenthetic “qualifiers.” These qualifiers indicate that these EPCRA Section 313 chemicals are subject to the section 313 reporting requirements if manufactured, processed, or otherwise used in a specific form or when a certain activity is performed. An EPCRA Section 313 chemical that is listed without a qualifier is subject to reporting in all forms in which it is manufactured, processed, and otherwise used. The following chemicals are reportable only if they are manufactured, processed, or otherwise used in the specific form(s) listed below: Chemical/ Chemical Category CAS Number Qualifier Aluminum (fume or dust) 7429-90-5 Only if it is a fume or dust form. -

Probabilistic Assessment of the Cumulative Acute Exposure to Organophosphorus and Carbamate Insecticides in the Brazilian Diet E.D

Toxicology 222 (2006) 132–142 Probabilistic assessment of the cumulative acute exposure to organophosphorus and carbamate insecticides in the Brazilian diet E.D. Caldas a,∗, P.E. Boon b, J. Tressou c a Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, College of Health Sciences, University of Bras´ılia, 70919-970 Bras´ılia, DF, Brazil b RIKILT, Institute of Food Safety, Wageningen University and Research Centre, 6708 PD Wageningen, The Netherlands c INRA, Unit´eM´et@risk, Methodologies d’analyse de risque alimentaire INA-PG, 75231 Paris, France Received 10 October 2005; received in revised form 1 February 2006; accepted 13 February 2006 Available online 6 March 2006 Abstract In the present study, the cumulative exposure of 25 acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibiting pesticides through the consumption of nine fruits and vegetables by the Brazilian population was assessed. Food consumption data were obtained from a household budget survey conducted in all Brazilian states from July 2002 to June 2003. Residue data from 4001 samples were obtained from the Brazilian national monitoring program on pesticide residues. Relative potency factors (RPF) were calculated with methamidophos or acephate as index compounds (IC), using BMD10 or NOAEL for AChE inhibition, mostly in rat brain, obtained from national and international pesticide evaluations. Monocrotophos and triazophos, in addition to aldicarb, had the highest calculated RPF in any scenario. The exposure to AChE inhibiting pesticides for the general population at P99.9, represented 33.6% of the ARfD as methamidophos and 70.2% ARfD as acephate. The exposure calculated as acephate could exceed the ARfD at the upper bound of the 95% confidence interval for this percentile. -

Code Chemical P026 1-(O-Chlorophenyl)Thiourea P081 1

Code Chemical P026 1-(o-Chlorophenyl)thiourea P081 1,2,3-Propanetriol, trinitrate (R) P042 1,2-Benzenediol, 4-[1-hydroxy-2-(methylamino)ethyl]-, (R)- P067 1,2-Propylenimine P185 1,3-Dithiolane-2-carboxaldehyde, 2,4-dimethyl-, O- [(methylamino)- carbonyl]oxime 1,4,5,8-Dimethanonaphthalene, 1,2,3,4,10,10-hexa- chloro-1,4,4a,5,8,8a,-hexahydro-, P004 (1alpha,4alpha, 4abeta,5alpha,8alpha,8abeta)- 1,4,5,8-Dimethanonaphthalene, 1,2,3,4,10,10-hexa- chloro-1,4,4a,5,8,8a-hexahydro-, P060 (1alpha,4alpha, 4abeta,5beta,8beta,8abeta)- P002 1-Acetyl-2-thiourea P048 2,4-Dinitrophenol P051 2,7:3,6-Dimethanonaphth [2,3-b]oxirene, 3,4,5,6,9,9 -hexachloro-1a,2,2a,3,6,6a,7,7a- octahydro-, (1aalpha,2beta,2abeta,3alpha,6alpha,6abeta,7 beta, 7aalpha)-, & metabolites 2,7:3,6-Dimethanonaphth[2,3-b]oxirene, 3,4,5,6,9,9- hexachloro-1a,2,2a,3,6,6a,7,7a- P037 octahydro-, (1aalpha,2beta,2aalpha,3beta,6beta,6aalpha,7 beta, 7aalpha)- P045 2-Butanone, 3,3-dimethyl-1-(methylthio)-, O-[methylamino)carbonyl] oxime P034 2-Cyclohexyl-4,6-dinitrophenol 2H-1-Benzopyran-2-one, 4-hydroxy-3-(3-oxo-1- phenylbutyl)-, & salts, when present at P001 concentrations greater than 0.3% P069 2-Methyllactonitrile P017 2-Propanone, 1-bromo- P005 2-Propen-1-ol P003 2-Propenal P102 2-Propyn-1-ol P007 3(2H)-Isoxazolone, 5-(aminomethyl)- P027 3-Chloropropionitrile P047 4,6-Dinitro-o-cresol, & salts P059 4,7-Methano-1H-indene, 1,4,5,6,7,8,8-heptachloro- 3a,4,7,7a-tetrahydro- P008 4-Aminopyridine P008 4-Pyridinamine P007 5-(Aminomethyl)-3-isoxazolol 6,9-Methano-2,4,3-benzodioxathiepin, 6,7,8,9,10,10- -

Aldicarb by Caroline Cox Pulses Across the Junctions Between Nerves

Aldicarb By Caroline Cox pulses across the junctions between nerves. (given over a one-year period). The high- This causes loss of muscular coordination, est dose at which no adverse effects were In 1966, four years before the insecticide convulsions, and ultimately death.5 The observed (called the NOEL) was 0.02 mg/ 11 aldicarb was registered for use in the United AChE inhibition is said to be reversible be- kg/day, about one-tenth of the LD50. States, researchers were using the chemical cause the aldicarb disassociates from the There is evidence that people may suf- on an experimental basis.1 One researcher AChE within several hours. This occurs even fer acute symptoms when exposed to even brought a small amount home and his wife if death has occurred. Organophosphate in- lower levels of aldicarb. In humans who applied it to the soil under a backyard rose secticides (malathion and diazinon, for ex- consumed aldicarb-contaminated water- bush. Over three weeks later she ate a sprig ample) have the same mode of action ex- melons, clinical signs of aldicarb poison- of mint from a plant growing nearby. Within cept that the AChE inhibition is not as ing were found in individuals consuming half an hour she was suffering from vomit- readily reversible.7 as little as 0.002 mg/kg of the aldicarb ing, diarrhea, and involuntary urination. Her Aldicarb is a systemic insecticide. It is metabolite aldicarb sulfoxide. This pupils closed to pinpoints, her muscles applied as granules below the soil surface amount is one-tenth the NOEL in the twitched, and her breathing was difficult. -

Healthcare Resource

Health Care Resource: Links between Pesticide Exposures and Mental Health Prepared by the Mental Health and Environment Working Group of the Collaborative on Health and the Environment www.healthandenvironment.org Mental Health Effects from Pesticide Exposure Exposure to pesticides can have behavioral and psychiatric consequences. The purpose of this resource is to help mental health clinicians and health care providers become aware of the association between pesticide exposure and these consequences and to provide links to relevant research findings. Many people are at risk of pesticide exposure, including those who: • work in agriculture, landscaping or other settings (such as grocery stores, schools, daycares and office buildings) in which pest problems are treated with chemicals; • live downwind from where aerial spraying of pesticides is done; • live in communities where spray and runoff can contaminate both surface and ground water; or • live in urban dwellings where pest control is used. Outside use may take months for the pesticide to degrade to half-life or roughly half potency. Indoors there are no degrading elements such as sunshine, soil or rain to degrade potency; these undegraded pesticides can be re-suspended into the air in dust particles. Health care providers should consider the possibility that the symptoms associated with mental health disorders, such as irritability, depression or anxiety, may be the result of acute or chronic pesticide exposure. No matter what the presenting ailment may be, clinicians who care for individuals either at risk of pesticide exposure or those with known exposure are encouraged to inquire about the presence of depression, anxiety, or any of the other symptoms listed below. -

For Aldicarb Reregistration Eligibility Decision (RED) Document for Aldicarb

United States Prevention, Pesticides EPA Environmental Protection and Toxic Substances September 2007 Agency (7508P) Reregistration Eligibility Decision for Aldicarb Reregistration Eligibility Decision (RED) Document for Aldicarb List A Case Number 0140 Approved by: Date: Steven Bradbury, Ph.D. Director Special Review and Reregistration Division Page 2 of 191 Table of Contents Aldicarb Reregistration Eligibility Decision Team ........................................................................ 5 Glossary of Terms and Abbreviations ............................................................................................ 6 Abstract........................................................................................................................................... 8 I. Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 9 II. Chemical Overview.................................................................................................................. 11 A. Chemical Identity..................................................................................................................11 B. Regulatory History ................................................................................................................12 C. Use and Usage Profile...........................................................................................................12 D. Tolerances .............................................................................................................................13 -

Organophosphate and Carbamate Pesticides

ORGANOPHOSPHATE AND CARBAMATE PESTICIDES What are ORGANOPHOSPHATE and CARBAMATE PESTICIDES? Organophosphates are phosphoric acid esters or thiophosphoric acid esters. When developed in the 1930s and 1940s, their original compounds were highly toxic to mammals. Organophosphates manufactured since then are less toxic to mammals but toxic to target organisms, such as insects. Malathion, dibrom, chlorpyrifos, temephos, diazinon and terbufos are organophosphates. Carbamates are esters of N-methyl carbamic acid. Aldicarb, carbaryl, propoxur, oxamyl and terbucarb are carbamates. Although these pesticides differ chemically, they act similarly. When applied to crops or directly to the soil as systemic insecticides, organophosphates and carbamates generally persist from only a few hours to several months. However, they have been fatal to large numbers of birds on turf and in agriculture, and negatively impacted breeding success in birds. Many organophosphates are highly toxic to aquatic organisms. How can people be exposed to organophosphate and carbamate pesticides? People can be exposed to organophosphates and carbamates pesticides through accidental exposure during use. People can accidentally inhale the pesticides if they are in an area where they were recently applied. The chemicals can be ingested with food or drinks that are contaminated. How can these pesticides exhaust affect my health? Acetylcholinesterase is an enzyme found in the nervous system, red blood cells and blood plasma. These pesticides damage nerve function by acting as acetylcholinesterase inhibitors in the nervous system. Breathing - Short-term exposure can produce muscle twitching, headache, nausea, dizziness, loss of memory, weakness, tremor, diarrhea, sweating, salivation, tearing, constriction of pupils, and slowed heartbeat. Long-term exposure can produce delayed neurotoxicity, such as tingling and burning in the extremities.