Katell Berthelot Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2 Maccabees, Chapter 1 Letter 1: 124 B.C

Archdiocese of St. Louis Office of Sacred Worship Lectio Divina Bible The Second Book of Maccabees Second Maccabees can be divided as follows: I. Letters to the Jews in Egypt II. Author’s Preface III. Heliodorus’ Attempt to Profane the Temple IV. Profanation and Persecution V. Victories of Judas and Purification of the Temple VI. Renewed Persecution VII. Epilogue * * * Lectio Divina Read the following passage four times. The first reading, simple read the scripture and pause for a minute. Listen to the passage with the ear of the heart. Don’t get distracted by intellectual types of questions about the passage. Just listen to what the passage is saying to you, right now. The second reading, look for a key word or phrase that draws your attention. Notice if any phrase, sentence or word stands out and gently begin to repeat it to yourself, allowing it to touch you deeply. No elaboration. In a group setting, you can share that word/phrase or simply pass. The third reading, pause for 2-3 minutes reflecting on “Where does the content of this reading touch my life today?” Notice what thoughts, feelings, and reflections arise within you. Let the words resound in your heart. What might God be asking of you through the scripture? In a group setting, you can share your reflection or simply pass. The fourth reading, pause for 2-3 minutes reflecting on “I believe that God wants me to . today/this week.” Notice any prayerful response that arises within you, for example a small prayer of gratitude or praise. -

THE BOOK of DANIEL and the "MACCABEAN THESIS" up Until

Andrews University Seminary Studies, Summer 1983, Vol. 21, No. 2, 129-141. Copyright @ 1983 by Andrews University Press. THE BOOK OF DANIEL AND THE "MACCABEAN THESIS" ARTHUR J. FERCH Avondale College Cooranbong, N. S. W. 2265 Australia Up until about a century ago, the claims laid out in the book of Daniel as to its authorship, origin, etc., during the sixth century B.C. were quite generally accepted. However, since 1890, according to Klaus Koch, this exilic theory has been seriously challenged-so much so, in fact, that today it represents only a minority view among Daniel scho1ars.l The majority hold a view akin to that of Porphyry, the third-century Neoplatonist enemy of Christianity, that the book of Daniel was composed (if not entirely, at least substantially) in the second century B.C. during the religious per- secution of the Jews by the Seleucid monarch Antiochus IV Epiphanes.2 The book is considered to have arisen in conjunction with, or in support of, the Jewish resistance to Antiochus led by Judas Maccabeus and his brothers. Thus, according to this view, designated as the "Maccabean the~is,"~the book of Daniel was composed (at least in part) and/or edited in the second century by an unknown author or authors who posed as a sixth-century statesman-prophet named Daniel and who pretended to offer genuinely inspired predictions (uaticinia ante eventu) which in reality were no more than historical narratives 'This article is based on a section of a paper presented in 1982 to the Daniel and Revelation Committee of the Biblical Research Institute (General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists, Washington, D.C.). -

Eng-Kjv 2MA.Pdf 2 Maccabees

2 Maccabees 1:1 1 2 Maccabees 1:10 The Second Book of the Maccabees 1 The brethren, the Jews that be at Jerusalem and in the land of Judea, wish unto the brethren, the Jews that are throughout Egypt health and peace: 2 God be gracious unto you, and remember his covenant that he made with Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, his faithful servants; 3 And give you all an heart to serve him, and to do his will, with a good courage and a willing mind; 4 And open your hearts in his law and commandments, and send you peace, 5 And hear your prayers, and be at one with you, and never forsake you in time of trouble. 6 And now we be here praying for you. 7 What time as Demetrius reigned, in the hundred threescore and ninth year, we the Jews wrote unto you in the extremity of trouble that came upon us in those years, from the time that Jason and his company revolted from the holy land and kingdom, 8 And burned the porch, and shed innocent blood: then we prayed unto the Lord, and were heard; we offered also sacrifices and fine flour, and lighted the lamps, and set forth the loaves. 9 And now see that ye keep the feast of tabernacles in the month Casleu. 10 In the hundred fourscore and eighth year, the people that were at Jerusalem and in Judea, and the council, and Judas, sent greeting and health unto Aristobulus, king Ptolemeus’ master, who was of the stock of the anointed priests, and to the Jews that were in Egypt: 2 Maccabees 1:11 2 2 Maccabees 1:20 11 Insomuch as God hath delivered us from great perils, we thank him highly, as having been in battle against a king. -

The Book of Common Prayer

The Book of Common Prayer and Administration of the Sacraments and Other Rites and Ceremonies of the Church Together with The Psalter or Psalms of David According to the use of The Episcopal Church Church Publishing Incorporated, New York Certificate I certify that this edition of The Book of Common Prayer has been compared with a certified copy of the Standard Book, as the Canon directs, and that it conforms thereto. Gregory Michael Howe Custodian of the Standard Book of Common Prayer January, 2007 Table of Contents The Ratification of the Book of Common Prayer 8 The Preface 9 Concerning the Service of the Church 13 The Calendar of the Church Year 15 The Daily Office Daily Morning Prayer: Rite One 37 Daily Evening Prayer: Rite One 61 Daily Morning Prayer: Rite Two 75 Noonday Prayer 103 Order of Worship for the Evening 108 Daily Evening Prayer: Rite Two 115 Compline 127 Daily Devotions for Individuals and Families 137 Table of Suggested Canticles 144 The Great Litany 148 The Collects: Traditional Seasons of the Year 159 Holy Days 185 Common of Saints 195 Various Occasions 199 The Collects: Contemporary Seasons of the Year 211 Holy Days 237 Common of Saints 246 Various Occasions 251 Proper Liturgies for Special Days Ash Wednesday 264 Palm Sunday 270 Maundy Thursday 274 Good Friday 276 Holy Saturday 283 The Great Vigil of Easter 285 Holy Baptism 299 The Holy Eucharist An Exhortation 316 A Penitential Order: Rite One 319 The Holy Eucharist: Rite One 323 A Penitential Order: Rite Two 351 The Holy Eucharist: Rite Two 355 Prayers of the People -

Syllabus, Deuterocanonical Books

The Deuterocanonical Books (Tobit, Judith, 1 & 2 Maccabees, Wisdom, Sirach, Baruch, and additions to Daniel & Esther) Caravaggio. Saint Jerome Writing (oil on canvas), c. 1605-1606. Galleria Borghese, Rome. with Dr. Bill Creasy Copyright © 2021 by Logos Educational Corporation. All rights reserved. No part of this course—audio, video, photography, maps, timelines or other media—may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage or retrieval devices without permission in writing or a licensing agreement from the copyright holder. Scripture texts in this work are taken from the New American Bible, revised edition © 2010, 1991, 1986, 1970 Confraternity of Christian Doctrine, Washington, D.C. and are used by permission of the copyright owner. All Rights Reserved. No part of the New American Bible may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the copyright owner. 2 The Deuterocanonical Books (Tobit, Judith, 1 & 2 Maccabees, Wisdom, Sirach, Baruch, and additions to Daniel & Esther) Traditional Authors: Various Traditional Dates Written: c. 250-100 B.C. Traditional Periods Covered: c. 250-100 B.C. Introduction The Deuterocanonical books are those books of Scripture written (for the most part) in Greek that are accepted by Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches as inspired, but they are not among the 39 books written in Hebrew accepted by Jews, nor are they accepted as Scripture by most Protestant denominations. The deuterocanonical books include: • Tobit • Judith • 1 Maccabees • 2 Maccabees • Wisdom (also called the Wisdom of Solomon) • Sirach (also called Ecclesiasticus) • Baruch, (including the Letter of Jeremiah) • Additions to Daniel o “Prayer of Azariah” and the “Song of the Three Holy Children” (Vulgate Daniel 3: 24- 90) o Suzanna (Daniel 13) o Bel and the Dragon (Daniel 14) • Additions to Esther Eastern Orthodox churches also include: 3 Maccabees, 4 Maccabees, 1 Esdras, Odes (which include the “Prayer of Manasseh”) and Psalm 151. -

2 Maccabees Reconsidered,“ ZNW 51 (1960) 10–30

21-2Mc-NETS-4.qxd 11/10/2009 10:31 PM Page 503 2 MAKKABEES TO THE READER EDITION OF THE GREEK TEXT The Greek text used as the basis of the present translation is R. Hanhart’s Göttingen edition, Maccabaeo- rum libri I-IV, 2: Maccabaeorum liber II, copiis usus quas reliquit Werner Kappler edidit Robert Hanhart (Septu- aginta: Vetus Testamentum Graecum Auctoritate Societatis Litterarum Göttingensis editum IX [Göttingen: Van- denhoeck & Ruprecht, 2nd ed., 1976 (1959)]), which forms part of the Göttingen Septuagint and is the standard critically established text of contemporary Septuagint scholarship. The texts provided by H. B. Swete, The Old Testament in Greek, According to the Septuagint (vol. 3; Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1912), A. Rahlfs, Septuaginta. Id est Vetus Testamentum graece iuxta LXX interpretes (9th ed.; Stuttgart: Württembergische Bibelanstalt, 1935) and F.-M. Abel, Les livres des Maccabées (Etudes Bibliques; Paris: J. Gabalda, 1949) were also consulted. It was not always possible to follow the text reconstructed by Hanhart. Wherever the present transla- tor’s textual-critical decisions differ from those of Hanhart, this has been indicated in the footnotes. Some of the considerations that necessitated such decisions are laid out in the next section. THE NETS TRANSLATION OF 2 MAKKABEES The Text of 2 Makkabees Any critical edition of 2 Makkabees relies mainly on two famous Greek uncial manuscripts: the Codex Alexandrinus (fifth century) and the Codex Venetus (eighth century). There is also a rich tradition of Greek minuscule manuscripts, as well as manuscript witnesses to Syriac, Armenian and Latin transla- tions. There also is a Coptic fragment of some passages from 2 Makk 5–6.1 Hanhart’s edition is based mainly on Alexandrinus and on minuscules 55, 347 and 771. -

“Not As the Gentiles”: Sexual Issues at the Interface Between Judaism And

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 16 July 2018 doi:10.20944/preprints201807.0284.v1 Peer-reviewed version available at Religions 2018, 9, 258; doi:10.3390/rel9090258 Article “Not as the Gentiles”: Sexual Issues at the Interface between Judaism and its Greco-Roman World William Loader, Murdoch University, [email protected] Abstract: Sexual Issues played a significant role in Judaism’s engagement with its Greco-Roman world. This paper will examine that engagement in the Hellenistic Greco-Roman era to the end of the first century CE. In part sexual issues were a key element of demarcation between Jews and the wider community, alongside such matters as circumcision, food laws, sabbath keeping and idolatry. Jewish writers, such as Philo of Alexandria, make much of the alleged sexual profligacy of their Gentile contemporaries, not least in association with wild drunken parties, same-sex relations and pederasty. Jews, including the emerging Christian movement, claimed the moral high ground. In part, however, matters of sexuality were also areas where intercultural influence is evident, such as in the shift in Jewish tradition from polygyny to monogyny, but also in the way Jewish and Christian writers adapted the suspicion and sometimes rejection of passions characteristic of some popular philosophies of their day, seeing them as allies in their moral crusade. Keywords: sexuality; Judaism; Greco-Roman 1. Introduction When the apostle Paul wrote to his recently founded community of believers that they were to behave “not as the Gentiles” in relation to sexual matters (1 Thess 4:5), he was standing in a long tradition of Jews demarcating themselves from their world over sexual issues. -

The Preview Edition

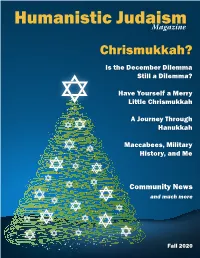

Humanistic Judaism Magazine Chrismukkah? Is the December Dilemma Still a Dilemma? Have Yourself a Merry Little Chrismukkah A Journey Through Hanukkah Maccabees, Military History, and Me Community News and much more Fall 2020 Table of Contents From SHJ Tributes, Board of Directors, p. 3 Communities p. 19–23 Maccabees, Military History, and Me p. 4–7 by Paul Golin Contributors Have Yourself a Merry Little Chrismukkah I Adam Chalom is the rabbi of Kol Hadash p. 8 Humanistic Congregation in Deerfield, IL and the by Rabbi Jeffrey L. Falick dean of the International Institute for Secular Humanistic Judaism (IISHJ). Is the December Dilemma Still a Dilemma? I Arty Dorman is a long-time member of Or Emet, Minnesota Congregation for Humanistic Judaism and p. 9 is the current Jewish Cultural School Director. by Rabbi Miriam Jerris I Lincoln Dow is the Community Organizer for Jews for a Secular Democracy. A Journey Through Hanukkah I Rachel Dreyfus, a CHJ member, is a professional p. 10, 16 marketing consultant, and project coordinator for OH! by Rabbi Adam Chalom I Jeffrey Falick is the Rabbi of The Birmingham Temple, Congregation for Humanistic Judaism. I Paul Golin is the Executive Director of the Society Hanukkah for Humanistic Judaism. p. 11 I Miriam Jerris is the Rabbi of the Society for Book Excerpt from God Optional Judaism Humanistic Judaism and the IISHJ Associate by Judith Seid Professor of Professional Development. I Herbert Levine is the author of two books of Richard Logan bi-lingual poetry, Words for Blessing the World (2017) and An Added Soul: Poems for a New Old p. -

Canons of the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament

Canons of the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament JEWISH TANAKH* PROTESTANT CATHOLIC ORTHODOX OLD TESTAMENT* OLD TESTAMENT* OLD TESTAMENT* Torah (Law or Instruction) The Five Books of Moses Pentateuch Pentateuch Bereshit (In the Beginning) Genesis Genesis Genesis Shemot (Names) Exodus Exodus Exodos VaYiqra (He summoned) Leviticus Leviticus Leuitikon BeMidbar (In the wilderness) Numbers Numbers Arithmoi Devarim (Words) Deuteronomy Deuteronomy Deuteronomion Nevi’im (Prophets) Historical Books Historical Books Histories Iesous Naue Yehoshua (Joshua) Joshua Josue Kritai (Judges) Shofetim (Judges) Judges Judges Routh Shemuel (Samuel) Ruth Ruth 1 Basileion (1 Reigns) Melachim (Kings) 1 Samuel 1 Kings (1 Samuel) 2 Basileion (2 Reigns) 2 Samuel 2 Kings (2 Samuel) 3 Basileion (3 Reigns) Yeshayahu (Isaiah) 1 Kings 3 Kings (1 Kings) 4 Basileion (4 Reigns) Yirmeyahu (Jeremiah) 2 Kings 4 Kings (2 Kings) 1 Paralipomenon (1 Supplements) Yechezkel (Ezekiel) 1 Chronicles 1 Paralipomenon 2 Paralipomenon (2 Supplements) 2 Chronicles 2 Paralipomenon Tere Asar (The Twelve) 1 Esdras (= 3 Esdras in the Ezra 1 Esdras (Ezra) Vulgate; parallels the conclusion Hoshea (Hosea) Nehemiah 2 Esdras (Nehemiah) of 2 Paralipomenon and 2 Esdras) Yoel (Joel) Esther Tobias 2 Esdras (Ezra+Nehemiah) Amos (Amos) Judith Esther (long version) Ovadyah (Obadiah) Poetic and Wisdom Books Esther (long version) Ioudith Yonah (Jonah) 1 Maccabees Job Tobit Michah (Micah) 2 Maccabees Psalms 1 Makkabaion Nachum (Nahum) Proverbs 2 Makkabaion Chavakuk (Habakkuk) Poetic and Wisdom Books Ecclesiastes -

Blessing & Dedication of the Synod Offices

A section of the Anglican Journal NOVEMBER 2015 IN THIS ISSUE Holy Cross Day at Holy Cross PAGES 10 & 11 A Church Recapturing Without the Momentum Walls or Keys of Reconciliation PAGES 12 – 14 PAGE 23 Blessing & Dedication of the Synod Offices The Eve of Holy Cross Day RANDY MURRAY Diocesan Communications Officer & Topic Editor “We shape our buildings; thereafter they shape us.” Winston Churchill The promotion material distributed by diocesan commu- nications inviting all interested people to attend the Open House, Blessing and Dedication of the Synod Offices and gathering spaces at 1410 Nanton Avenue on September 13, 2015, perhaps gave the impression that the event would be like the opening of a high rise tower a business, or perhaps a gated subdivision. But that was certainly not the case. This was first and foremost, worship, a liturgy glorifying God, asking the Creator to bless this place, the people who use the place and the work and ministry that is done in Jesus’ name in this place. The Blessing and Dedication marked the end of years of discussion, visioning, negotiating and planning, and marked the completion of months of engineering, design- ing and building. Not just building, but renovating and repurposing an existing structure, bestowing upon it the components and fixtures necessary to be a gathering place from which the mission and ministry of the diocese of New Westminster can emanate. Therefore, the Blessing and Dedication also marked a beginning, a fresh start and a renewed purpose for this place located in the venerable, stately, extremely expensive neighbourhood of Shaughnessy. -

Possible Misreading in 1 Maccabees 7:34 in Light of Its Biblical Model

JBL 138, no. 4 (2019): 777–789 https://doi.org/10.15699/jbl.1384.2019.5 Possible Misreading in 1 Maccabees 7:34 in Light of Its Biblical Model matan orian [email protected] Center for the Study of Conversion and Inter-Religious Encounters, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Beer Sheva, 8410501, Israel First Maccabees 7:34 employs four verbs to describe the offensive speech by Nicanor, the Seleucid general, addressed to the Jewish elders and priests. The third verb indicates that Nicanor defiled his audience. While this has led scholars to associate 1 Maccabees with the Jewish concept of gentile impurity, several factors suggest that, at this point, an error found its way into the Greek translation from the original Hebrew. The present argument comprises three steps. First, I use the biblical Sennacherib story, featured in the background of the Nicanor episode in 1 Maccabees, as a means of reconstructing the relevant original Hebrew verb employed by 1 Maccabees. Second, I suggest a possible misreading of one letter on the part of the Greek translator. Finally, I propose that a similar, earlier verse in 1 Maccabees, 1:24b, may have been conducive to the translator’s commission of this mistake, thus offering an insight into his way of thinking. I. A Verb Clearly out of Context First Maccabees 7:34 employs four verbs to describe the insulting nature of the speech by Nicanor, the Seleucid general, directed at the Jewish elders and the priests of the Jerusalem temple who emerged from the temple to greet him: “he mocked them, derided them, defiled them, and spoke arrogantly” (ἐμυκτήρισεν αὐτοὺς καὶ κατεγέλασεν αὐτῶν καὶ ἐμίανεν αὐτοὺς καὶ ἐλάλησεν ὑπερηφάνως).1 The third verb, “defile,” plainly differs from the other verbs in this verse: it does not relate to the nature of the speech but rather to a cultic or ritual consequence of some physical act committed by Nicanor. -

The Septuagint As a Holy Text – the First 'Bible' of the Early Church

HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies ISSN: (Online) 2072-8050, (Print) 0259-9422 Page 1 of 9 Original Research The Septuagint as a holy text – The first ‘bible’ of the early church Author: This article acknowledges the fact that historically there are two phases in the emergence of the 1 Johann Cook Septuagint – a Jewish phase and a Christian one. The article deals first with methodological Affiliation: issues. It then offers a historical orientation. In the past some scholars have failed to distinguish 1Department of Ancient between key historical phases: the pre-exilic/exilic (Israelite – 10 tribes), the exilic (the Studies, Faculty of Arts and Babylonian exile ‒ 2 tribes) and the post-exilic (Judaean/Jewish). Many scholars are unaware Social Sciences, University of of the full significance of the Hellenistic era, including the Seleucid and Ptolemaic eras and Stellenbosch, Stellenbosch, South Africa their impact on ‘biblical’ textual material. Others again overestimate the significance of this era; the Greek scholar Evangelia Dafni is an example. Many are uninformed about the Persian Corresponding author: era, which includes the Achaemenid, Parthian and Sassanian eras, each one of which had an Johann Cook, impact on Judaism. An example is the impact of Persian dualism. Another problem is the [email protected] application of the concept of ‘the Bible’. The notion of ‘Bible’ applies only after the 16th century Dates: Common Era, specifically after the advent of the printing press. Earlier, depending on the Received: 18 May 2020 context, we had clay tablets (Mesopotamia), vella (Levant-Judah) and papyri (Egypt) to write Accepted: 06 July 2020 on.