A Shape for Queerness: Glimpses, Loops, Holes, Language

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

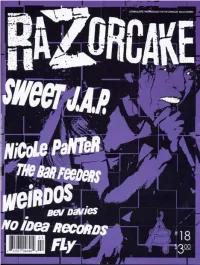

Razorcake Issue #09

PO Box 42129, Los Angeles, CA 90042 www.razorcake.com #9 know I’m supposed to be jaded. I’ve been hanging around girl found out that the show we’d booked in her town was in a punk rock for so long. I’ve seen so many shows. I’ve bar and she and her friends couldn’t get in, she set up a IIwatched so many bands and fads and zines and people second, all-ages show for us in her town. In fact, everywhere come and go. I’m now at that point in my life where a lot of I went, people were taking matters into their own hands. They kids at all-ages shows really are half my age. By all rights, were setting up independent bookstores and info shops and art it’s time for me to start acting like a grumpy old man, declare galleries and zine libraries and makeshift venues. Every town punk rock dead, and start whining about how bands today are I went to inspired me a little more. just second-rate knock-offs of the bands that I grew up loving. hen, I thought about all these books about punk rock Hell, I should be writing stories about “back in the day” for that have been coming out lately, and about all the jaded Spin by now. But, somehow, the requisite feelings of being TTold guys talking about how things were more vital back jaded are eluding me. In fact, I’m downright optimistic. in the day. But I remember a lot of those days and that “How can this be?” you ask. -

Read Razorcake Issue #27 As A

t’s never been easy. On average, I put sixty to seventy hours a Yesterday, some of us had helped our friend Chris move, and before we week into Razorcake. Basically, our crew does something that’s moved his stereo, we played the Rhythm Chicken’s new 7”. In the paus- IInot supposed to happen. Our budget is tiny. We operate out of a es between furious Chicken overtures, a guy yelled, “Hooray!” We had small apartment with half of the front room and a bedroom converted adopted our battle call. into a full-time office. We all work our asses off. In the past ten years, That evening, a couple bottles of whiskey later, after great sets by I’ve learned how to fix computers, how to set up networks, how to trou- Giant Haystacks and the Abi Yoyos, after one of our crew projectile bleshoot software. Not because I want to, but because we don’t have the vomited with deft precision and another crewmember suffered a poten- money to hire anybody to do it for us. The stinky underbelly of DIY is tially broken collarbone, This Is My Fist! took to the six-inch stage at finding out that you’ve got to master mundane and difficult things when The Poison Apple in L.A. We yelled and danced so much that stiff peo- you least want to. ple with sourpusses on their faces slunk to the back. We incited under- Co-founder Sean Carswell and I went on a weeklong tour with our aged hipster dancing. -

The Long History of Indigenous Rock, Metal, and Punk

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Not All Killed by John Wayne: The Long History of Indigenous Rock, Metal, and Punk 1940s to the Present A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in American Indian Studies by Kristen Le Amber Martinez 2019 © Copyright by Kristen Le Amber Martinez 2019 ABSTRACT OF THESIS Not All Killed by John Wayne: Indigenous Rock ‘n’ Roll, Metal, and Punk History 1940s to the Present by Kristen Le Amber Martinez Master of Arts in American Indian Studies University of California Los Angeles, 2019 Professor Maylei Blackwell, Chair In looking at the contribution of Indigenous punk and hard rock bands, there has been a long history of punk that started in Northern Arizona, as well as a current diverse scene in the Southwest ranging from punk, ska, metal, doom, sludge, blues, and black metal. Diné, Apache, Hopi, Pueblo, Gila, Yaqui, and O’odham bands are currently creating vast punk and metal music scenes. In this thesis, I argue that Native punk is not just a cultural movement, but a form of survivance. Bands utilize punk and their stories as a conduit to counteract issues of victimhood as well as challenge imposed mechanisms of settler colonialism, racism, misogyny, homophobia, notions of being fixed in the past, as well as bringing awareness to genocide and missing and murdered Indigenous women. Through D.I.Y. and space making, bands are writing music which ii resonates with them, and are utilizing their own venues, promotions, zines, unique fashion, and lyrics to tell their stories. -

APRIL 22 ISSUE Orders Due March 24 MUSIC • FILM • MERCH Axis.Wmg.Com 4/22/17 RSD AUDIO & VIDEO RECAP

2017 NEW RELEASE SPECIAL APRIL 22 ISSUE Orders Due March 24 MUSIC • FILM • MERCH axis.wmg.com 4/22/17 RSD AUDIO & VIDEO RECAP ARTIST TITLE LBL CNF UPC SEL # SRP ORDERS DUE Le Soleil Est Pres de Moi (12" Single Air Splatter Vinyl)(Record Store Day PRH A 190295857370 559589 14.98 3/24/17 Exclusive) Anni-Frid Frida (Vinyl)(Record Store Day Exclusive) PRL A 190295838744 60247-P 21.98 3/24/17 Wild Season (feat. Florence Banks & Steelz Welch)(Explicit)(Vinyl Single)(Record WB S 054391960221 558713 7.98 3/24/17 Store Day Exclusive) Cracked Actor (Live Los Angeles, Bowie, David PRH A 190295869373 559537 39.98 3/24/17 '74)(3LP)(Record Store Day Exclusive) BOWPROMO (GEM Promo LP)(1LP Vinyl Bowie, David PRH A 190295875329 559540 54.98 3/24/17 Box)(Record Store Day Exclusive) Live at the Agora, 1978. (2LP)(Record Cars, The ECG A 081227940867 559102 29.98 3/24/17 Store Day Exclusive) Live from Los Angeles (Vinyl)(Record Clark, Brandy WB A 093624913894 558896 14.98 3/24/17 Store Day Exclusive) Greatest Hits Acoustic (2LP Picture Cure, The ECG A 081227940812 559251 31.98 3/24/17 Disc)(Record Store Day Exclusive) Greatest Hits (2LP Picture Disc)(Record Cure, The ECG A 081227940805 559252 31.98 3/24/17 Store Day Exclusive) Groove Is In The Heart / What Is Love? Deee-Lite ECG A 081227940980 66622 14.98 3/24/17 (Pink Vinyl)(Record Store Day Exclusive) Coral Fang (Explicit)(Red Vinyl)(Record Distillers, The RRW A 081227941468 48420 21.98 3/24/17 Store Day Exclusive) Live At The Matrix '67 (Vinyl)(Record Doors, The ECG A 081227940881 559094 21.98 3/24/17 -

The Genre Formerly Known As Punk: a Queer Person of Color's Perspective on the Scene Shane M

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Scripps Senior Theses Scripps Student Scholarship 2014 The Genre Formerly Known As Punk: A Queer Person of Color's Perspective on the Scene Shane M. Zackery Scripps College Recommended Citation Zackery, Shane M., "The Genre Formerly Known As Punk: A Queer Person of Color's Perspective on the Scene" (2014). Scripps Senior Theses. 334. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses/334 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Scripps Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scripps Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE GENRE FORMERLY KNOWN AS “PUNK”: A QPOC’S PERSPECTIVE ON THE SCENE Shane Zackery Scripps College Claremont CA, 91711 1 THE GENRE FORMERLY KNOWN AS “PUNK”: A QPOC’S PERSPECTIVE ON THE SCENE Abstract This video is a visual representation of the frustrations that I suffered from when I, a queer, gender non-conforming, person of color, went to “pasty normals” (a term defined by Jose Esteban Munoz to describe normative, non-exotic individuals) to get a definition of what Punk meant and where I fit into it. In this video, I personify the Punk music movement. Through my actions, I depart from the grainy, low-quality, amateur aesthetics of the Punk film and music genres and create a new world where the Queer Person of Color defines Punk. In the piece, Punk definitively says, “Don’t try to define me. Shut up and leave me to rest.” 2 1 Conceptualization My project will be an experimental performance video that incorporates monologues, performances, visual sound elements, and still and moving images. -

Punk · Film RARE PERIODICALS RARE

We specialize in RARE JOURNALS, PERIODICALS and MAGAZINES Please ask for our Catalogues and come to visit us at: rare PERIODIcAlS http://antiq.benjamins.com music · pop · beat · PUNk · fIlM RARE PERIODICALS Search from our Website for Unusual, Rare, Obscure - complete sets and special issues of journals, in the best possible condition. Avant Garde Art Documentation Concrete Art Fluxus Visual Poetry Small Press Publications Little Magazines Artist Periodicals De-Luxe editions CAT. Beat Periodicals 296 Underground and Counterculture and much more Catalogue No. 296 (2016) JOHN BENJAMINS ANTIQUARIAT Visiting address: Klaprozenweg 75G · 1033 NN Amsterdam · The Netherlands Postal address: P.O. BOX 36224 · 1020 ME Amsterdam · The Netherlands tel +31 20 630 4747 · fax +31 20 673 9773 · [email protected] JOHN BENJAMINS ANTIQUARIAT B.V. AMSTERDAM cat.296.cover.indd 1 05/10/2016 12:39:06 antiquarian PERIODIcAlS MUSIC · POP · BEAT · PUNK · FILM Cover illustrations: DOWN BEAT ROLLING STONE [#19111] page 13 [#18885] page 62 BOSTON ROCK FLIPSIDE [#18939] page 7 [#18941] page 18 MAXIMUM ROCKNROLL HEAVEN [#16254] page 36 [#18606] page 24 Conditions of sale see inside back-cover Catalogue No. 296 (2016) JOHN BENJAMINS ANTIQUARIAT B.V. AMSTERDAM 111111111111111 [#18466] DE L’AME POUR L’AME. The Patti Smith Fan Club Journal Numbers 5 and 6 (out of 8 published). October 1977 [With Related Ephemera]. - July 1978. [Richmond Center, WI]: (The Patti Smith Fan Club), (1978). Both first editions. 4to., 28x21,5 cm. side-stapled wraps. Photo-offset duplicated. Both fine, in original mailing envelopes (both opened a bit rough but otherwise good condition). EUR 1,200.00 Fanzine published in Wisconsin by Nanalee Berry with help from Patti’s mom Beverly. -

Tony Hawk's Underground 2: Remix

wru.thu92online.com AcJiVISiox. activision.com lCflVlSloX bia Paciflc,tevel 5,51 BarsonSl, EIph! xsw ?i?1, AuilElia O2m5 mvision Pubrhhing.Inc. Acllvbion isareqistered tadema*aodTflUG s atadema*0i Adlbion Publbhinq,lnc All ilqib Bsefled.TonyHawkb aindemafr oirony Hawk,lnc. PSP version developed by Neve6offEnletuinment, Inc. and shak. MemoryStick 0uorM nay bercquked Gold separalely). Ali dghtsreseod- All olhertmdematuand tade namesarelhe propedyor thenrespedlve owners 80739.260.AU ULES.OO033 '+ , 'Plays&tiou", , UMo ad "608@'@ hdeMb or qi$d tEdemdsoi Sny Compu@E&ftinmm @. -tF' AllnigilsReed. ffi1ro2265 i:::::::i:,.,:,4,:,r.:.rur.,.,,,,1: PRECAUTIONS ',rl:tl1llt:irri::;:iil.i, ThisdisccontainsgamesoftwareforthePSPrM(Playstation@Portable)system.Neverusethis::: on anyother system, as it coulddamage it. Readthe PSPrM system Instruction Manual carefui , :: ensurecorect usage. Do not leave the disc near heat sources or in directsunlight or exces:.. moisture.Do not use cracked or deformed discs or discsthat have been repaired with adhesives :! 2 thiscould iead to mal{unction. I Pushdown one sldeofthe Placethe disc as shoer dkc as shown and gentiy pull gently pressingdownf,- ( upwards to remove lt. Usinq until it clickslito pl.r. excesslorce to temove the Storing the disc incon:: disc may result n damage, may retult in dam.ge. 8 B HEALTHWARNING Alwaysplay in a welllit environment. Take regular breaks, 15 minutesevery hour Avoid p aynq Y whentired or suffering from lack of sleep.Some individuals are sensitive lo flashing or flickerlng Iightsor geometricshapes and patterns, may have an undetectedepileptic condition and maJ WalkingandClimbing. ..."...9 experienceepileplic seizures when watching television or playingvideogames. Consult your Tagging. doctorbefore playing videogames ifyou have an epileptic condition and immediately should you experienceany of the followingsymptoms whilst playing: dizziness, altered vision, muscle ControlTips h{itching,other involuntary movement. -

Chapter 1 “The Sons of Sid Vicious”

CHAPTER 1 “THE SONS OF SID VICIOUS” SECTION OF THE SLAM PIT abruptly came to a halt and fanned out. Three from the Pig Children gang started to advance, and then another four moved on us. Each one was a true Philistine: sizable, A smelly, disgusting. Santino pulled his box cutter out and started slic- ing and dicing at anything that moved. The Governor and I were pushing and kicking for more space. Every inch mattered. A few guys ran off bleeding. One Pig Child got hold of Santino, they struggled briefly, but the inevitable always happened … blood poured. I counted six slashes to the chest. The guy’s face turned white, reality set in, and down he went. “LMP! Want some, get some!” threatened Santino. Everybody backed the fuck up—the great equalizer once again proved its point. Shock seeped in as they surrounded their fallen. Panic in Pig Park. Santino, The Governor, and I stood tall—heads cocked back, eyes of evil. The Pig Children took an even harder look and realized there were only three of us, with no backup, and started to rally numbers. Next thing we knew, a good 30 or 40 guys were coming at us from every direction yelling, “Get ’em!” We went at it. I dropped one and then two, steady as ever. The Governor was trading bombs and holding his own. Santino nailed a few with his fists then sliced an- other. Funny thing was, the Pig Children were hitting their own people as much as us. That’s what happens when you rage fight. -

Punk Passage: California and Beyond, 1977-1981 Photographs by Ruby Ray Mining Denver’S Underground Rock Photography: Seldom Seen Scenes in Local Music

Exhibitions: Punk Passage: California and Beyond, 1977-1981 Photographs by Ruby Ray Mining Denver’s Underground Rock Photography: seldom seen scenes in local music. Group show curated by Cinthea Fiss Dates: March 29–May 12, 2012 Public Reception: Thursday, March 29, 6-9 pm. Featuring live music by Fritz Fox of The Mutants. Members’ Preview Reception 5-6 pm. Organized by: Rupert Jenkins & Richard Peterson Place: Colorado Photographic Arts Center, 445 South Saulsbury Street, Lakewood, CO 80226 Hours: TU–SA 12–5.30 pm Events: Music Scene: Presentations and Critiques by Ruby Ray, Richard Peterson, and Cinthea Fiss Date: Saturday March 31, 1-4.30 pm. Place: CPAC Cost: $10/5 presentations only; $25/15 with portfolio critique Punk Passage: California and Beyond, 1977-1981 will be shown at CPAC alongside Mining Denver’s Underground Rock Photography: seldom seen scenes in local music, an exhibition of new Denver music photography curated by Cinthea Fiss. Both exhibitions are presented in collaboration with Search & Destroy, a series of citywide exhibitions, concerts and events in Denver exploring punk’s historical and ongoing relationship to visual art, coordinated around the exhibition Bruce Conner and the Primal Scene of Punk Rock at the Museum of Contemporary Art Denver. Partner institutions include Art-Plant, Carmen Wiedenhoeft Gallery, Colorado Photographic Arts Center, Gildar Gallery, Hi-Dive, Lion's Lair, Museum of Contemporary Art Denver and Underground Music Showcase. Mining Denver Rock Photography artists: [email protected], John Schoenwalter, Jason Bye, Brenda LaBier, Spike Photography Exhibition celebrates San Francisco’s explosive Punk Scene of the late 70s In 1977, punk broke through the world psyche like a jackhammer. -

Sexuality in the Horror Soundtrack (1968-1981)

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Monstrous Resonance: Sexuality in the Horror Soundtrack (1968-1981) A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Musicology by Morgan Fifield Woolsey 2018 © Copyright by Morgan Fifield Woolsey 2018 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Monstrous Resonance: Sexuality in the Horror Soundtrack (1968-1981) by Morgan Fifield Woolsey Doctor of Philosophy in Musicology University of California, Los Angeles, 2018 Professor Raymond L. Knapp, Co-Chair Professor Mitchell Bryan Morris, Co-Chair In this dissertation I argue for the importance of the film soundtrack as affective archive through a consideration of the horror soundtrack. Long dismissed by scholars in both cinema media studies and musicology as one of horror’s many manipulative special effects employed in the aesthetically and ideologically uncomplicated goal of arousing fear, the horror soundtrack is in fact an invaluable resource for scholars seeking to historicize changes in cultural sensibilities and public feelings about sexuality. I explore the critical potential of the horror soundtrack as affective archive through formal and theoretical analysis of the role of music in the representation of sexuality in the horror film. I focus on films consumed in the Unites States during the 1970s, a decade marked by rapid shifts in both cultural understanding and cinematic representation of sexuality. ii My analyses proceed from an interdisciplinary theoretical framework animated by methods drawn from affect studies, American studies, feminist film theory, film music studies, queer of color critique, and queer theory. What is the relationship between public discourses of fear around gender, race, class, and sexuality, and the musical framing of sexuality as fearful in the horror film? I explore this central question through the examination of significant figures in the genre (the vampire, the mad scientist/creation dyad, and the slasher or serial killer) and the musical-affective economies in which they circulate. -

QS 204, Queer Identity: Pop Music and Its Audience, 1980'S To

New Course Proposal – Page 1/18 NEW COURSE PROPOSAL College: [ Humanities ] Department: [ Queer Studies ] Note: Use this form to request a single course that can be offered independently of any other course, lab or activity. 1. Course information for Catalog Entry Subject Abbreviation and Number: [ QS 204 ] Course Title: [ Queer Identity: Pop Music and Its Audience, 1980’s to Now ] Units: [ 3 ] units Course Prerequisites: [ ] (if any) Course Corequisites: [ ] (if any) Recommended Preparatory Courses: [ ] (if any) 2. Course Description for Printed Catalog: Notes: If grading is NC/CR only, please state in course description. If a course numbered less than 500 is available for graduate credit, please state “Available for graduate credit in the catalog description.” [This course analyzes queer identity and its relation to pop music since the 1980’s, focusing primarily on explicit representations of LGBTQ themes, experiences, characters, and communities in pop music. Course themes include positive images, creation of alternative space, AIDS, coming out, celebrity, and the gay audience. Through close readings of queer theory and criticism, we will analyze the phenomenon of queer music by exploring the contested relationships between spectator and text, identity and commodity, realism and fantasy, activism and entertainment, desire and politics. QS 204 is an elective for the QS Minor. ] 3. Date of Proposed Implementation: (Semester/Year): [ Spring ] / [ 2018 ] Comments Early Implementation as part of the response to the pressing need and as part of a proposed sequence of new courses in concert with existing QS courses (S18: QS204, QS304; F18: QS205; S19: QS208; F19: QS369) 4. Course Level [ X ]Undergraduate Only [ ]Graduate Only [ ]Graduate/Undergraduate 5. -

His Eyes Looked Like Eggs, with the Yolks Broken Open, With

PO Box 42129, Los Angeles, CA 90042 #18 www.razorcake.com picked off the road, and sewn back on. If he didn’t move with such is eyes looked like eggs, with the yolks broken open, with authority, it’d’ve been easy to mistake him as broken. bits of blood pulsing through them. Before he even opened His voice caught me off guard. It was soft, resonant. “What’re HHup his grease stained tennis bag, I knew that there was you looking for?” nothing I’d want to buy from him. He unzipped the bag. Inside, “Foot pegs.” I didn’t have to give him the make and model. He there were ten or fifteen carburetors. Obviously freshly stolen, the knew from the connecting bolt I held out. rubber fuel lines cut raggedly and gas leaking out. “Got ‘em. Don’t haggle with me. You got the cash?” I placed “No. I’m just looking for foot pegs.” the money in his hand. “Man, you could really help me out. Sure you don’t want an “That’s what I like. Cash can’t bounce. Follow me.” upgrade? There’s some nice ones in here.” We weaved through dusty corridors, the halls strategically There were some very expensive pieces of metal, highly mined with Doberman shit. To the untrained eye, the place looked polished, winking at me. I could almost hear the death threats their in shambles. No care was taken to preserve the carpet. Inside-facing previous owners’ bellowed into empty parking lots. windows were smashed out. He bent down, opened a drawer with a “No.