Indians in the American System: Past and Present, Student Book. the Lavinia and Charles P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mike Mangini

/.%/&4(2%% 02):%3&2/- -".#0'(0%4$)3*4"%-&34&55*/(4*()54 7). 9!-!(!$25-3 VALUED ATOVER -ARCH 4HE7ORLDS$RUM-AGAZINE 0/5)& '0$64)*)"5 "$)*&7&5)&$-"44*$ 48*/(406/% "35#-",&: 5)&.&/503 50%%46$)&3."/ 45:-&"/%"/"-:4*4 $2%!-4(%!4%23 Ê / Ê" Ê," Ê/"Ê"6 , /Ê-1 -- (3&(03:)65$)*/40/ 8)&3&+";;41"45"/%'6563&.&&5 #6*-%:06308/ .6-5*1&%"-4&561 -ODERN$RUMMERCOM 3&7*&8&% 5"."4*-7&345"33&.0108&34530,&130-6%8*("5-"4130)"3%8"3&3*.4)05-0$."55/0-"/$:.#"-4 Volume 36, Number 3 • Cover photo by Paul La Raia CONTENTS Paul La Raia Courtesy of Mapex 40 SETTING SIGHTS: CHRIS ADLER Lamb of God’s tireless sticksman embraces his natural lefty tendencies. by Ken Micallef Timothy Saccenti 54 MIKE MANGINI By creating layers of complex rhythms that complement Dream Theater’s epic arrangements, “the new guy” is ushering in a bold and exciting era for the band, its fans, and progressive rock music itself. by Mike Haid 44 GREGORY HUTCHINSON Hutch might just be the jazz drummer’s jazz drummer— historically astute and futuristically minded, with the kind 12 UPDATE of technique, soul, and sophistication that today’s most important artists treasure. • Manraze’s PAUL COOK by Ken Micallef • Jazz Vet JOEL TAYLOR • NRBQ’s CONRAD CHOUCROUN • Rebel Rocker HANK WILLIAMS III Chuck Parker 32 SHOP TALK Create a Stable Multi-Pedal Setup 36 PORTRAITS NYC Pocket Master TONY MASON 98 WHAT DO YOU KNOW ABOUT...? Faust’s WERNER “ZAPPI” DIERMAIER One of Three Incredible 70 INFLUENCES: ART BLAKEY Prizes From Yamaha Drums Enter to Win We all know those iconic black-and-white images: Blakey at the Valued $ kit, sweat beads on his forehead, a flash in the eyes, and that at Over 5,700 pg 85 mouth agape—sometimes with the tongue flat out—in pure elation. -

My Bloody Valentine's Loveless David R

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2006 My Bloody Valentine's Loveless David R. Fisher Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC MY BLOODY VALENTINE’S LOVELESS By David R. Fisher A thesis submitted to the College of Music In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2006 The members of the Committee approve the thesis of David Fisher on March 29, 2006. ______________________________ Charles E. Brewer Professor Directing Thesis ______________________________ Frank Gunderson Committee Member ______________________________ Evan Jones Outside Committee M ember The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables......................................................................................................................iv Abstract................................................................................................................................v 1. THE ORIGINS OF THE SHOEGAZER.........................................................................1 2. A BIOGRAPHICAL ACCOUNT OF MY BLOODY VALENTINE.………..………17 3. AN ANALYSIS OF MY BLOODY VALENTINE’S LOVELESS...............................28 4. LOVELESS AND ITS LEGACY...................................................................................50 BIBLIOGRAPHY..............................................................................................................63 -

Jazz – Pop – Rock Gesamtliste Stand Januar 2021

Jazz – Pop – Rock Gesamtliste Stand Januar 2021 50 Cent Thing is back CD 1441 77 Bombay Str. Up in the Sky CD 1332 77 Bombay Street Oko Town CD 1442 77 Bombay Street Seven Mountains CD 1684 7 Dollar Taxi Bomb Shelter Romance CD 1903 Abba The Definitive Collection CD 1085 Abba Gold CD 243 Abba (Feat.) Mamma Mia! Feat. Abba CD 992 Above & Beyond We are all we need CD 1643 AC/DC Black Ice CD 1044 AC/DC Rock or Bust CD 1627 Adams, Bryan Tracks of my Years CD 1611 Adams, Bryan Reckless CD 1689 Adele Adele 19 CD 1009 Adele Adele: 21 CD 1285 Adele Adele 25 CD 1703 Aguilera, Christina Liberation CD 1831 a-ha 25 Twenty Five CD 1239 Airbow, Tenzin Reflecting Signs CD 1924 Albin Brun/Patricia Draeger Glisch d’atun CD 1849 Ali Erol CD 1801 Allen, Lily It’s not Me, it’s You CD 1550 Allen, Lily Sheezus CD 1574 Alt-J An Awsome Wave CD 1503 Alt-J This is all yours CD 1637 Alt-J This is all yours, too CD 1654 Amir Au Cœurs de moi CD 1730 Girac, Kendji Amigo CD 1842 Anastacia Heavy rotation CD 1301 Anastacia Resurrection CD 1587 Angèle Brol la Suite CD 1916 Anthony, Marc El Cantante CD 1676 Arctic Monkeys Whatever people say CD 1617 Armatrading, Joan Starlight CD 1423 Ärzte, Die Jazz ist anders CD 911 Aslan Hype CD 1818 Avicii Tim CD 1892 Avidan, Assaf Gold Shadow CD 1669 Azcano, Juli Distancias CD 1851 Azcano, Julio/Arroyo, M. New Tango Songbook CD 1850 Baba Shrimps Neon CD 1570 Baker, Bastian Tomorrow may not be better CD 1397 Baker, Bastian Noël’s Room CD 1481 Baker, Bastian Too old to die young CD 1531 Baker, Bastian Facing Canyons CD 1702 Bailey Rae, Corinne The Heart speaks in Whispers CD 1733 Barclay James H. -

Billboard-1997-08-30

$6.95 (CAN.), £4.95 (U.K.), Y2,500 (JAPAN) $5.95 (U.S.), IN MUSIC NEWS BBXHCCVR *****xX 3 -DIGIT 908 ;90807GEE374EM0021 BLBD 595 001 032898 2 126 1212 MONTY GREENLY 3740 ELM AVE APT A LONG BEACH CA 90807 Hall & Oates Return With New Push Records Set PAGE 1 2 THE INTERNATIONAL NEWSWEEKLY OF MUSIC, VIDEO AND HOME ENTERTAINMENT AUGUST 30, 1997 ADVERTISEMENTS 4th -Qtr. Prospects Bright, WMG Assesses Its Future Though Challenges Remain Despite Setbacks, Daly Sees Turnaround BY CRAIG ROSEN be an up year, and I think we are on Retail, Labels Hopeful Indies See Better Sales, the right roll," he says. LOS ANGELES -Warner Music That sense of guarded optimism About New Releases But Returns Still High Group (WMG) co- chairman Bob Daly was reflected at the annual WEA NOT YOUR BY DON JEFFREY BY CHRIS MORRIS looks at 1997 as a transitional year for marketing managers meeting in late and DOUG REECE the company, July. When WEA TYPICAL LOS ANGELES -The consensus which has endured chairman /CEO NEW YORK- Record labels and among independent labels and distribu- a spate of negative m David Mount retailers are looking forward to this tors is that the worst is over as they look press in the last addressed atten- OPEN AND year's all- important fourth quarter forward to a good holiday season. But few years. Despite WARNER MUSI C GROUP INC. dees, the mood with reactions rang- some express con- a disappointing was not one of SHUT CASE. ing from excited to NEWS ANALYSIS cern about contin- second quarter that saw Warner panic or defeat, but clear -eyed vision cautiously opti- ued high returns Music's earnings drop 24% from last mixed with some frustration. -

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: an Analysis Into Graphic Design's

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres by Vivian Le A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems (Honors Scholar) Presented May 29, 2020 Commencement June 2020 AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Vivian Le for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems presented on May 29, 2020. Title: Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres. Abstract approved:_____________________________________________________ Ryann Reynolds-McIlnay The rise of digital streaming has largely impacted the way the average listener consumes music. Consequentially, while the role of album art has evolved to meet the changes in music technology, it is hard to measure the effect of digital streaming on modern album art. This research seeks to determine whether or not graphic design still plays a role in marketing information about the music, such as its genre, to the consumer. It does so through two studies: 1. A computer visual analysis that measures color dominance of an image, and 2. A mixed-design lab experiment with volunteer participants who attempt to assess the genre of a given album. Findings from the first study show that color scheme models created from album samples cannot be used to predict the genre of an album. Further findings from the second theory show that consumers pay a significant amount of attention to album covers, enough to be able to correctly assess the genre of an album most of the time. -

Idioms-And-Expressions.Pdf

Idioms and Expressions by David Holmes A method for learning and remembering idioms and expressions I wrote this model as a teaching device during the time I was working in Bangkok, Thai- land, as a legal editor and language consultant, with one of the Big Four Legal and Tax companies, KPMG (during my afternoon job) after teaching at the university. When I had no legal documents to edit and no individual advising to do (which was quite frequently) I would sit at my desk, (like some old character out of a Charles Dickens’ novel) and prepare language materials to be used for helping professionals who had learned English as a second language—for even up to fifteen years in school—but who were still unable to follow a movie in English, understand the World News on TV, or converse in a colloquial style, because they’d never had a chance to hear and learn com- mon, everyday expressions such as, “It’s a done deal!” or “Drop whatever you’re doing.” Because misunderstandings of such idioms and expressions frequently caused miscom- munication between our management teams and foreign clients, I was asked to try to as- sist. I am happy to be able to share the materials that follow, such as they are, in the hope that they may be of some use and benefit to others. The simple teaching device I used was three-fold: 1. Make a note of an idiom/expression 2. Define and explain it in understandable words (including synonyms.) 3. Give at least three sample sentences to illustrate how the expression is used in context. -

Resources March 10, 2018

Appleton Public Montessori Diversity & Inclusion Committee Resources March 10, 2018 General Diversity Local Resources ● Books ● Videos ● Websites ○ African Heritage Incorporated https://www.africanheritageinc.org/ ○ Casa Hispania http://www.casahispanawi.org/ ○ Celebrate Diversity http://www.celebratediversityfoxcities.com/ ○ Community Foundation https://www.cffoxvalley.org/2017/05/09/fox-cities-working-on- diversity/ ○ Diverse & Resilient https://www.diverseandresilient.org/ ○ Fox Valley Resources http://www.lawrence.edu/info/offices/diversity-and- inclusion/resources/fox-valley-diversity-resources ○ Hmong American Partnership Fox Valley https://www.hapfv.org/ ○ LGBTQ Chamber of Commerce https://wislgbtchamber.com/diverse-resilient/ ○ MId-Day Women’s Alliance https://middaywomensalliance.wildapricot.org/ ○ The New North http://thenewnorth.com/talent/diversity-resources/diversity-resource-guides/ National Resources ● Books ● Videos ● Websites ○ Diversity Best Practice http://www.diversitybestpractices.com/2017-diversity-holidays ○ Reading Diversely FAQ: https://bookriot.com/2015/01/15/reading-diversely-faq-part-1/ ○ Zinn Education Project https://zinnedproject.org/ ● Children’s books in general, including issues of diversity: ○ The Horn Book (and the The Horn Book Guide) http://www.hbook.com/ ○ School Library Journal, including the blogs Fuse 8 Production http://blogs.slj.com/afuse8production/ and 100 Scope Notes http://100scopenotes.com/ ● More specifically oriented toward diversity in children’s literature ○ Booktoss blog by Laura Jiménez: -

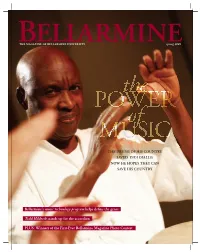

Bellarmine's Music Technology Program Helps Define the Genre Todd Hildreth Stands up for the Accordion PLUS

THE MAGAZINE OF BELLARMINE UNIVERSITY spring 2009 the POWER of MUSIC THE DRUMS OF HIS COUNTRY SAVED YAYA DIALLO; NOW HE HOPES THEY CAN SAVE HIS COUNTRY Bellarmine’s music technology program helps define the genre Todd Hildreth stands up for the accordion PLUS: Winners of the First-Ever Bellarmine Magazine Photo Contest 2 BELLARMINE MAGAZINE TABLE of CEONT NTS 5 FROM THE PRESIDENT Helping Bellarmine navigate tough times 6 THE READERS WRITE Letters to the editor 7 ‘SUITE FOR RED RIVER GORGE, PART ONE’ A poem by Lynnell Edwards 7 WHAT’S ON… The mind of Dr. Kathryn West 8 News on the Hill 14 FIRST-EVER BELLARMINE MAGAZINE PHOTO CONTEST The winners! 20 QUESTION & ANSWER Todd Hildreth has a squeezebox – and he’s not afraid to use it 22 DRUM CIRCLE Yaya Diallo’s music has taken him on an amazing journey 27 CONCORD CLASSIC This crazy thing called the Internet 28 BELLARMINE RADIO MAKES SOME NOISE Shaking up the lineup with more original programming 32 NEW HARMONY Fast-growing music technology program operates between composition and computers 34 CLASS NOTES 36 Alumni Corner 38 THE ALUMNI ASSOCIATION COVER: DRUMMER YAYA DIALLO BRINGS THE HEALING ENERGY. —page 22 LEFT: FANS CHEER THE KNIGHTS TO ANOTHER VICTORY. COVER PHOTO BY GEOFF OLIVER BUGBEE PHOTO AT LEFT BY BRIAN TIRPAK spring 2009 3 from THE EDITOR Harmonic convergence OFFICERS OF THE UNIVERSITY DR. JOSEPH J. MCGOWAN President WHB EN ELLARMINE MAGAZINE CONTRIBUTOR KATIE KELTY WENT TO The Concord archives in search of a flashback story for this issue’s “Concord Classic,” she DR. -

Garbage Shut Your Mouth (Radio Version) Mp3, Flac, Wma

Garbage Shut Your Mouth (Radio Version) mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Shut Your Mouth (Radio Version) Country: UK Released: 2002 Style: Alternative Rock, Pop Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1509 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1897 mb WMA version RAR size: 1693 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 868 Other Formats: AU AIFF VOC AA MOD MP3 MP2 Tracklist 1 Shut Your Mouth (Radio Version) 3:25 Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Mushroom Records (UK) Ltd. Copyright (c) – Mushroom Records (UK) Ltd. Published By – Deadarm Music Published By – Almo Music Corp. Published By – Vibecrusher Music Published By – Irving Music, Inc. Mastered At – Classic Sound, New York Pressed By – Sonopress – 50357162 Credits Bass – Daniel Shulman Engineer – Billy Bush Mastered By – Scott Hull Written-By, Producer – Butch Vig, Duke Erikson, Garbage, Shirley Manson, Steve Marker Notes Taken from the album: beautifulgarbage Promo only not for sale Barcode and Other Identifiers Matrix / Runout: Sonopress 50357162/TRASH46 03 Mastering SID Code: IFPI LB 45 Mould SID Code: IFPI 0711 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Shut Your Australia MUSH106CDS Garbage Mouth (CD, Mushroom MUSH106CDS & New 2002 Single) Zealand Shut Your Mouthº¹ (CD, MUSH106CDS Garbage Mushroom MUSH106CDS UK 2002 Single, Enh, CD1) Shut Your Play It Again 720.0106.122, 720.0106.122, Garbage Mouth (CD, Sam [PIAS], Europe 2002 MUSH106CDM MUSH106CDM Single) Mushroom Shut Your TRASH47 Garbage Mouth (12", Mushroom TRASH47 UK 2002 Promo) Shut Your MUSH106CDSXX Garbage Mouth°³ (CD, Mushroom MUSH106CDSXX UK 2002 Single, Car) Related Music albums to Shut Your Mouth (Radio Version) by Garbage Garbage - Why Do You Love Me Garbage - Version 2.0 / Beautiful Garbage Garbage - Run Baby Run Garbage - I Think I'm Paranoid Garbage - Version 2.0 Garbage - Only Happy When It Rains Garbage - Beautiful Garbage Garbage - Lick The Pavement Garbage - Queer Garbage - Garbage. -

Brand New Cd & Dvd Releases 2006 6,400 Titles

BRAND NEW CD & DVD RELEASES 2006 6,400 TITLES COB RECORDS, PORTHMADOG, GWYNEDD,WALES, U.K. LL49 9NA Tel. 01766 512170: Fax. 01766 513185: www. cobrecords.com // e-mail [email protected] CDs, DVDs Supplied World-Wide At Discount Prices – Exports Tax Free SYMBOLS USED - IMP = Imports. r/m = remastered. + = extra tracks. D/Dble = Double CD. *** = previously listed at a higher price, now reduced Please read this listing in conjunction with our “ CDs AT SPECIAL PRICES” feature as some of the more mainstream titles may be available at cheaper prices in that listing. Please note that all items listed on this 2006 6,400 titles listing are all of U.K. manufacture (apart from Imports which are denoted IM or IMP). Titles listed on our list of SPECIALS are a mix of U.K. and E.C. manufactured product. We will supply you with whichever item for the price/country of manufacture you choose to order. ************************************************************************************************************* (We Thank You For Using Stock Numbers Quoted On Left) 337 AFTER HOURS/G.DULLI ballads for little hyenas X5 11.60 239 ANATA conductor’s departure B5 12.00 327 AFTER THE FIRE a t f 2 B4 11.50 232 ANATHEMA a fine day to exit B4 11.50 ST Price Price 304 AG get dirty radio B5 12.00 272 ANDERSON, IAN collection Double X1 13.70 NO Code £. 215 AGAINST ALL AUTHOR restoration of chaos B5 12.00 347 ANDERSON, JON animatioin X2 12.80 92 ? & THE MYSTERIANS best of P8 8.30 305 AGALAH you already know B5 12.00 274 ANDERSON, JON tour of the universe DVD B7 13.00 -

Enacting Cultural Identity : Time and Memory in 20Th-Century African-American Theater by Female Playwrights

Enacting Cultural Identity: Time and Memory in 20th-Century African-American Theater by Female Playwrights Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades des Doktors der Philosophie (Dr. phil.) vorgelegt von Simone Friederike Paulun an der Geisteswissenschaftliche Sektion Fachbereich Literaturwissenschaft Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 13. Februar 2012 Referentin: Prof. Dr. Dr. h.c. Aleida Assmann Referentin: PD Dr. Monika Reif-Hülser Konstanzer Online-Publikations-System (KOPS) URL: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bsz:352-0-269861 Acknowledgements 1 Acknowledgements This dissertation would not have been possible without the guidance and support of several individuals who in one way or another contributed to the writing and completion of this study. It gives me a great pleasure to acknowledge the help of my supervisor Prof Dr. Aleida Assmann who has supported me throughout my thesis and whose knowledge, guidance, and encouragement undoubtedly highly benefited my project. I would also like to thank PD Dr. Monika Reif-Hülser for her sustained interest in my work. The feedback that I received from her and the other members of Prof. Assmann’s research colloquium was a very fruitful source of inspiration for my work. The seeds for this study were first planted by Prof. David Krasner’s course on African- American Theater, Drama, and Performance that I attended while I was an exchange student at Yale University, USA, in 2005/2006. I am immensely grateful to him for introducing me to this fascinating field of study and for sharing his expert knowledge when we met again in December 2010. A further semester of residence as a visiting scholar at the African American Department at Yale University in 2010 enabled me to receive invaluable advice from Prof. -

Singing Japan's Heart and Soul

Smith ScholarWorks East Asian Languages & Cultures: Faculty Publications East Asian Languages & Cultures 7-19-2012 Singing Japan’s Heart and Soul: A Discourse on the Black Enka Singer Jero and Race Politics in Japan Neriko Musha Doerr Ramapo College Yuri Kumagai Smith College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.smith.edu/eas_facpubs Part of the Japanese Studies Commons Recommended Citation Doerr, Neriko Musha and Kumagai, Yuri, "Singing Japan’s Heart and Soul: A Discourse on the Black Enka Singer Jero and Race Politics in Japan" (2012). East Asian Languages & Cultures: Faculty Publications, Smith College, Northampton, MA. https://scholarworks.smith.edu/eas_facpubs/4 This Article has been accepted for inclusion in East Asian Languages & Cultures: Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Smith ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected] ICS15610.1177/1367877912451688Doerr and KumagaiInternational Journal of Cultural Studies 4516882012 International Journal of Cultural Studies 15(6) 599 –614 © The Author(s) 2012 Reprints and permission: sagepub.co.uk/ journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/1367877912451688 ics.sagepub.com Article Singing Japan’s heart and soul: A discourse on the black enka singer Jero and race politics in Japan Neriko Musha Doerr Ramapo College, USA Yuri Kumagai Smith College, USA Abstract This article analyses a discourse around the ascendancy of Jero, an ‘African-American’ male dressed in hip-hop attire singing enka, a genre of music that has been dubbed ‘the heart and soul of Japan.’ Since his debut in Japan in February 2008, Jero has attracted much media attention. This article analyses a prominent discourse, ‘Jero is almost Japanese because he sings enka well.’ While many argue that to challenge stereotypes and racism is to introduce alternative role models, we show that such alternative role models can also reinforce the existing regime of difference of Japanese vs.