SMC2011 Tiffon Sprenger-Ohana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Workshop for Young Composers

THE LATVIAN NATIONAL SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA INVITES YOU TO THE INTERNATIONAL WORKSHOP FOR YOUNG COMPOSERS Latvia’s top symphonic player, the Latvian National Symphony Orchestra (LNSO), reintroduces the international workshop for young composers. Andris Dzenītis, one of Latvia’s most excellent composers, developed the tradition by attracting numerous young authors to workshops in various Latvia’s cities – Dundaga, Cēsis, and Mazsalaca. The workshops will take place on 19–23 August, 2019, in Rēzekne – a city in the heart of Latvia’s most peculiar region Latgale. Workshop participants will have the opportunity to draw inspiration from the oldest layers of North Latgale’s traditional music. The workshop lecturers are: Andris Dzenītis (Latvia), Marco Stroppa (Italy/Germany), and Anders Nordentoft (Denmark). The workshop will conclude with a performance of the participants’ new works in the opening concert of the LNSO Summer Festival at the Latgale Embassy GORS Small Hall. THEME – METAMORPHOSIS OF NORTHERN LATGALE’S TRADITIONAL SONGS LATGALE is a glorious lakeland in the southeast of Latvia. It is the poorest and the wealthiest part of the country simultaneously: a region with the least successful economy and the richest traditional culture and music. Historically, the territory of Latvia (and Estonia) adopted Lutheranism in the 16th century, except for Latgale, which was under Polish rule at the time and remained Catholic. Another specific feature of Latgale is that the majority of population speak the Latgalian, or High Latvian language. This form of Latvian has its own literature, and the relation between the Latvian of the Lutheran regions and Latgale’s High Latvian makes an approximate analogy to the relation between the High German and Low German or even High German and Dutch. -

Patricia Alessandrini – Biography

Patricia Alessandrini – Biography Patricia Alessandrini’s works, principally involving live electronics, actively engage with the concert music repertoire, and issues of representation, interpretation, perception and memory. She has become increasingly involved in multimedia, theatrical and collaborative work, often involving social and political issues. Her compositions have been presented in new music festivals including Agora (Paris), Archipel (Geneva), Festival de la imagen (Manizales), Festival en tiempo real (Bogotá), Festival Synthèse (Bourges), Musica Strasbourg, Musiques Démesurées (Clermont-Ferrand), Musiques Inventives d’Annecy, Pacific New Music Festival (California), Sonorities (Belfast), Sound and Fury (NYC), and Miso Music Portugal – 25 Years (Lisbon), and performed by ensembles including Accroche Note, Arditti Quartet, Ensemble Aleph, Ensemble Alternance, Ensemble InterContemporain, Ensemble Itinéraire, Ensemble Vortex, Ives Quartet, New Millennium, Speculum Musicae, and Talujon Quartet. She has composed music for the Ballet de l’Opéra National du Rhin, and collaborated with institutions such as the Groupe de Recherches Musicales (GRM), Institut de Recherche et Coordination Acoustique/Musique (IRCAM), La Muse en Circuit, Musiques Inventives d’Annecy, Elektronmusikstudion (EMS, Stockholm) and other centres of research and production. She studied composition with Ivan Fedele, Paul Koonce, Tristan Murail, and Thea Musgrave, and participated in courses with Richard Ayres, Franco Donatoni, Brian Ferneyhough, Beat Furrer, Jonathan Harvey, Michael Jarrell, Betsy Jolas, Helmut Lachenmann, David Lang, Pär Lindgren, Philippe Manoury and Marco Stroppa. She attended an experimental course in composition and live electronics at the Conservatorio di Bologna with Adriano Guarnieri and Alvise Vidolin, the One-Year Course in Composition and Computer Music of IRCAM, and IRCAM’s Cursus II, involving the production of a multimedia project. -

0012762KAI.Pdf

REBECCA SAUNDERS (*1967) 1 choler (2004) 16:52 für zwei Klaviere 2 crimson (2004–05) 17:35 für Klavier 3 miniata (2004) 32:16 für Akkordeon, Klavier, Chor und Orchester TT: 66:49 1 2 3 Nicolas Hodges Klavier 1 Rolf Hind Klavier 3 Teodoro Anzellotti Akkordeon 3 licenced by col legno SWR Vokalensemble Stuttgart SWR Sinfonieorchester Baden-Baden und Freiburg Hans Zender Coverphoto: © Peter Oswald 2 Zwischen Klang und Dunkelheit, zwischen Stille und Licht Drei Werke für und mit Klavier von Rebecca Saunders Björn Gottstein Wer, wie Rebecca Saunders, mit Eltern aufwächst, für crimson, das in Anlehnung an das mittlerwei- die sich beide als Pianisten verdingen, in einem le zurückgezogene Solo (2002) und an das Piano Haus, das voller Klaviere steht, der verbringt als solo aus der Tanztheatermusik Insideout (2003) Kind ganze Nachmittage unter dem Flügel, um entstanden ist und das ihre pianistischen Arbeiten den Klang der vibrierenden Saiten über sich hin- auf ihren – so Saunders wörtlich: „Kern“ reduziert: weg strömen zu lassen. „Das Klavier war allge- „Es geht um eine ganz schmale Palette von Klang- genwärtig und allmächtig“, beschreibt Saunders farben, Klängen und Ausdrucksmöglichkeiten, die ihr gespaltenes Verhältnis zu einem Instrument, dann in diesem Stück miteinander verschmolzen das in ihrer Kindheit beides gewesen ist: Zuflucht werden.“ und Pantheon. Zu dieser Palette gehören zahlreiche Clusterva- Das Klavier ist für Saunders noch heute ein wich- rianten, stumm gedrückte Tasten mit frei reso- tiges, ja vielleicht das wichtigste Instrument. Mehr nierenden Saiten, extreme Lagen, dynamische noch als von ihr zur Signatur erkorene Instrumente Kontraste, vor allem aber der virtuose Umgang wie der Kontrabass, die E-Gitarre oder die Spiel- mit dem Sustain-, dem Sostenuto- und dem Una uhr, ist das Klavier so sehr in ihrem musikalischen corda-Pedal. -

Ensemble Intercontemporain Matthias Pintscher, Music Director

Friday, November 6, 2015, 8pm Hertz Hall Ensemble intercontemporain Matthias Pintscher, Music Director PROGRAM Marco Stroppa (b. 1959) gla-dya. Études sur les rayonnements jumeaux (2006–2007) 1. Languido, lascivo (langoureux, lascif) 2. Vispo (guilleret) 3. Come una tenzone (comme un combat) 4. Lunare, umido (lunaire, humide) 5. Scottante (brûlant) Jens McManama, horn Jean-Christophe Vervoitte, horn Frank Bedrossian (b. 1971) We met as Sparks (2015) United States première Emmanuelle Ophèle, bass flute Alain Billard, contrabass clarinet Odile Auboin, viola Éric-Maria Couturier, cello 19 PROGRAM Beat Furrer (b. 1954) linea dell’orizzonte (2012) INTERMISSION Kurt Hentschläger (b. 1960)* Cluster.X (2015) Edmund Campion (b. 1957) United States première Kurt Hentschläger, electronic surround soundtrack and video Edmund Campion, instrumental score and live processing Jeff Lubow, software (CNMAT) * Audiovisual artist Kurt Hentschläger in collaboration with composer Edmund Campion. Ensemble intercontemporain’s U.S. tour is sponsored by the City of Paris and the French Institute. Additional support is provided by the FACE Foundation Contemporary Music Fund. This performance is made possible, in part, by Patron Sponsor Ross Armstrong, in memory of Jonas (Jay) Stern. Hamburg Steinway piano provided by Steinway & Sons of San Francisco. Cal Performances’ – season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. PLAYBILL ORCHESTRA ROSTER ENSEMBLE INTERCONTEMPORAIN Emmanuelle Ophèle flute, bass flute Didier Pateau oboe Philippe Grauvogel oboe Jérôme Comte clarinet Alain -

MARCO STROPPA Miniature Estrose – Primo Libro Per Pianoforte D’Amore

MARCO STROPPA Miniature Estrose – Primo Libro per pianoforte d’amore Erik Bertsch © Roberto Masotti Marco Stroppa (*1959) Miniature Estrose Primo Libro (1991 – 2003; rev. 2009) 1 Passacaglia canonica, in contrappunto policromatico 08:30 2 Birichino, come un furetto 03:41 3 Moai 09:56 4 Ninnananna 06:04 5 Tangata Manu 10:00 6 Innige Cavatina 11:40 7 Prologos: Anagnorisis I. Canones diversi ad consequendum 13:08 TT 63:00 Erik Bertsch, piano 3 Miniature Estrose “Miniature” as it is used here does not no. Each Miniatura is based on a com- so much refer to a piece that is brief plex system of resonances created by as it does to one that is fashioned in a sizeable number of keys being low- great detail, like the elaborately dec- ered silently prior to the performance orated initials of medieval illuminated and then held by the sostenuto ped- manuscripts or some of the miniatures al, leaving the relative strings free to from India. “Estrose” is an untrans- vibrate throughout the duration of latable word with various shades of the Miniatura. In this manner, the oth- meaning, having to do with imagina- er notes played interact with the free tion, creative intuition, inspiration and strings, generating countless sympa- genius, but also extravagance and ec- thetic resonances and giving rise to centricity. Suffice it to say that Antonio the formation of latent harmony. This Vivaldi chose this same word for his mechanism, which lies at the basis of L’Estro Armonico. a metamorphosed instrument which Stroppa refers to as the pianoforte Marco Stroppa, from d’amore, demands a radical change Miniature Estrose, Primo Libro – from the performer in his or her ap- Casa Ricordi, Milano proach to the piano. -

Télécharger La Lettre De Présences 2020

CONCERTS MAISON DE LA RADIO FESTIVAL PRÉSENCES 2020 DU 7 AU 16 FÉVRIER GEORGE BENJAMIN UN PORTRAIT FESTIVAL DE CRÉATION MUSICALE DE RADIO FRANCE – 30e ÉDITION GEORGE BENJAMIN © CHRISTOPHE ABRAMOWITZ GEORGE BENJAMIN EST LE HÉROS DE LA TRENTIÈME ÉDITION DE PRÉSENCES. CRÉÉ PAR CLAUDE SAMUEL EN 1991, LE FESTIVAL A PERMIS DE DÉFENDRE ET ILLUSTRER GEORGE BENJAMIN EN 9 DATES LA MUSIQUE D’AUJOURD’HUI EN INVITANT DES FIGURES TUTÉLAIRES DE LA SECONDE 1960 1976 1980 1985 1992 2001 2006 2012 2018 E MOITIÉ DU XX SIÈCLE (XENAKIS, BERIO, LIGETI ET QUELQUES AUTRES) ET EN Naissance Étudie au Ringed by the Flat Enseigne à la Royal Fonde le festival Tient la chaire Création Création de l’opéra Création de l’opéra à Londres. Conservatoire Horizon est joué School of Music « Wet Ink » à San de composition d’Into the Little Hill Written on Skin Lessons in Love and FAISANT LA PART BELLE À LA DÉCOUVERTE. APRÈS KAIJA SAARIAHO EN 2017, PUIS de Paris avec aux Proms de de Londres. Francisco, consacré Henry Purcell au lors du Festival au Festival Violence à Covent Olivier Messiaen Londres. à la musique King’s College de d’Automne à Paris. d’Aix-en-Provence. Garden. THIERRY ESCAICH ET WOLFGANG RIHM, L’AVENTURE SE POURSUIT CETTE ANNÉE et Yvonne Loriod. d’aujourd’hui. Londres. EN COMPAGNIE D’UN MUSICIEN ANGLAIS QUI FUT ÉLÈVE D’OLIVIER MESSIAEN ET A MARQUÉ LES ESPRITS AVEC (NOTAMMENT) SON OPÉRA WRITTEN ON THE SKIN. D’AUTRES COMPOSITEURS, BIEN SÛR, SONT À L’AFFICHE DU FESTIVAL, ET PRÉSENCES VOUS CONFESSEZ UNE AFFECTION PARTICULIÈRE POUR LA SEPTIÈME DE NOUS FAIT NOUS RÉJOUIR D’ÊTRE LEURS CONTEMPORAINS. -

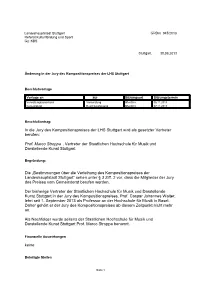

KSD Redaktionssystem

Landeshauptstadt Stuttgart GRDrs 945/2013 Referat Kultur/Bildung und Sport Gz: KBS Stuttgart, 30.09.2013 Änderung in der Jury des Kompositionspreises der LHS Stuttgart Beschlußvorlage Vorlage an zur Sitzungsart Sitzungstermin Verwaltungsausschuss Vorberatung öffentlich 06.11.2013 Gemeinderat Beschlussfassung öffentlich 07.11.2013 Beschlußantrag: In die Jury des Kompositionspreises der LHS Stuttgart wird als gesetzter Vertreter berufen: Prof. Marco Stroppa , Vertreter der Staatlichen Hochschule für Musik und Darstellende Kunst Stuttgart Begründung: Die „Bestimmungen über die Verleihung des Kompositionspreises der Landeshauptstadt Stuttgart“ sehen unter § 3 Ziff. 2 vor, dass die Mitglieder der Jury des Preises vom Gemeinderat berufen werden. Der bisherige Vertreter der Staatlichen Hochschule für Musik und Darstellende Kunst Stuttgart in der Jury des Kompositionspreises, Prof. Caspar Johannes Walter, lehrt seit 1. September 2013 als Professor an der Hochschule für Musik in Basel. Daher gehört er der Jury des Kompositionspreises ab diesem Zeitpunkt nicht mehr an. Als Nachfolger wurde seitens der Staatlichen Hochschule für Musik und Darstellende Kunst Stuttgart Prof. Marco Stroppa benannt. Finanzielle Auswirkungen keine Beteiligte Stellen Seite 1 keine Vorliegende Anträge/Anfragen keine Erledigte Anträge/Anfragen keine Dr. Susanne Eisenmann Anlagen Anlage 1: Vita Marco Stroppa Seite 2 Vita Marco Stroppa Der Komponist, Forscher und Dozent Marco Stroppa begann seine Musikstudien in Italien (Diplom in Klavier, Komposition, Chorleitung und Elektronische Musik). Er perfektionierte in der Zeit von 1984 bis 1986 seine wissenschaftlichen Kenntnisse am Massachusetts Institute of Technology in den USA (Kognitive Psychologie, Informatik und Künstliche Intelligenz). Von 1980 bis 1984 arbeitete er mit dem Computerklangforschungszentrum der Universität Padua zusammen. Auf Einladung von Pierre Boulez zog er 1982 nach Paris, um als Komponist und Forscher am IRCAM zu arbeiten. -

Compact Discs / DVD-Blu-Ray Recent Releases - Spring 2017

Compact Discs / DVD-Blu-ray Recent Releases - Spring 2017 Compact Discs 2L Records Under The Wing of The Rock. 4 sound discs $24.98 2L Records ©2016 2L 119 SACD 7041888520924 Music by Sally Beamish, Benjamin Britten, Henning Kraggerud, Arne Nordheim, and Olav Anton Thommessen. With Soon-Mi Chung, Henning Kraggerud, and Oslo Camerata. Hybrid SACD. http://www.tfront.com/p-399168-under-the-wing-of-the-rock.aspx 4tay Records Hoover, Katherine, Requiem For The Innocent. 1 sound disc $17.98 4tay Records ©2016 4TAY 4048 681585404829 Katherine Hoover: The Last Invocation -- Echo -- Prayer In Time of War -- Peace Is The Way -- Paul Davies: Ave Maria -- David Lipten: A Widow’s Song -- How To -- Katherine Hoover: Requiem For The Innocent. Performed by the New York Virtuoso Singers. http://www.tfront.com/p-415481-requiem-for-the-innocent.aspx Rozow, Shie, Musical Fantasy. 1 sound disc $17.98 4tay Records ©2016 4TAY 4047 2 681585404720 Contents: Fantasia Appassionata -- Expedition -- Fantasy in Flight -- Destination Unknown -- Journey -- Uncharted Territory -- Esme’s Moon -- Old Friends -- Ananke. With Robert Thies, piano; The Lyris Quartet; Luke Maurer, viola; Brian O’Connor, French horn. http://www.tfront.com/p-410070-musical-fantasy.aspx Zaimont, Judith Lang, Pure, Cool (Water) : Symphony No. 4; Piano Trio No. 1 (Russian Summer). 1 sound disc $17.98 4tay Records ©2016 4TAY 4003 2 888295336697 With the Janacek Philharmonic Orchestra; Peter Winograd, violin; Peter Wyrick, cello; Joanne Polk, piano. http://www.tfront.com/p-398594-pure-cool-water-symphony-no-4-piano-trio-no-1-russian-summer.aspx Aca Records Trios For Viola d'Amore and Flute. -

Programme De Salle

Document de communication du Festival d'Automne à Paris - tous droits réservés Helmut Lachenmann Trio Fluido pour clarinette, alto et percussion Pression pour violoncelle Dal Niente pour clarinette temA pour flûte, voix et violoncelle Toccatina pour violon Intérieur I pour percussion Entretien avec le compositeur et présentation du cycle Helmut Lachenmann Trio à cordes Ensemble Recherche, Freiburg Salut fur Caudwell, Linda Hirst, soprano pour deux guitaristes Wilhelm Bruck et Theodor Ross, guitare Eric Tanguy Quatuor à cordes nol Accanto, musique pour un clarinettiste avec orchestre Toshio Hosokawa Landscape Ausklang, Péter atvôs pour piano et orchestre Korrespondenz Helmut Lachenmann Eduard Brunner, clarinette Reigen seliger Geister Massimiliano Damerini, piano Orchestre Symphonique du Südwestfunk, Quatuor Arditti Baden- Baden Direction, Zoltan Pesko Coproduction Festival d'Automne à Paris, Radio France Concert enregistré par France Musique Helmut Lachenmann "...Zwei Gefühle...", Musik mit Leonardo (création en France) Helmut Lachenmann Guero Gran Torso pour piano Allegro sostenuto pour clarinette, violoncelle et piano Marco Stroppa Mouvement (-vor der Erstarrung) Miniature estrose, pour piano (création de la version intégrale) Ensemble Modern, Francfort Direction, Markus Stenz Quatuor de Berne Pierre-Laurent Aimard, piano Coproduction Festival d'Automne à Paris, Opéra de Paris Bastille Les cinq concerts consacrés à l'oeuvre de Helmut Lachenmann sont réalisés avec le concours de l'Association Française d'Action Artistique, de la Sacem, en co-réalisation avec le Goethe-Institut Production : Festival d'Automne à Paris. Co-producteurs : Radio France et Opéra de Paris Bastille Directrice artistique, Joséphine Markovits. Conseiller, Philippe Albèra. Coordination de la publication, Peter Szendy. Assistante, Shan Benson Le Festival d'Automne à Paris est subventionné par le Ministère de la Culture et de la Francophonie, le Ministère des Affaires Etrangères, la Ville deParis, Présidente, Janine Alexandre-Debray. -

Arbeitsberichte 171 NO. 94 MARCO

NO. 94 MARCO STROPPA A composer, researcher, and teacher, Marco Stroppa (born in 1959 in Verona) studied music in Italy (piano, composition, electronic music) and computer science, cognitive psychology, and AI at MIT’s Media Laboratory (1984–86). In 1980, he composed Traiettoria, which immediately met with great success. In 1982, Pierre Boulez invited him to Ircam (Paris). His uninterrupted association with it has been crucial to his musical growth. A highly respected educator, Stroppa founded the composition course at the Bartók Festival in Szombathély, Hungary, where he taught for 13 years. In 1999, he became Professor of Composition at the State University of Music and the Performing Arts in Stuttgart, the successor of Helmut Lachenmann. Often assembled in the form of thematic cycles, his works draw inspiration from a wide range of experiences: reading poetic and mythological texts, a deep engagement in ecological and socio-political issues, the study of ethnomusicology, and his personal contact with the performers, including Pierre-Laurent Aimard. He in- vented the term “acoustic totem” for The Enormous Room, a cycle of works for solo instru- ments and “chamber electronics” based on poems by E. E. Cummings. Stroppa has writ- ten more than 50 essays about his music research. His first opera (Re Orso, King Bear), on a text by Arrigo Boito, premiered with great success in May 2012 at the Opéra Comique in Paris. – Address: Staatliche Hochschule für Musik und Darstellende Kunst, Urban- straße 25, 70182 Stuttgart, Germany. E-mail: [email protected]. In Haydn’s most famous musical joke, the quiet, gentle slow movement of Symphony No. -

Konzerte Zum 80. Geburtstag Von Helmut Lachenmann

Konzerte zum 80. Geburtstag von Helmut Lachenmann Fr 13. November 2015, 20 Uhr Sa 14. November 2015, 15 und 20 Uhr Theaterhaus Stuttgart 1 Programm Samstag, 14. November 2015, 15 Uhr Theaterhaus Stuttgart, T3–T1 attacca – geistesgegenwart.musik 13. bis 14. November 2015 Pierluigi Billone Theaterhaus Stuttgart »Equilibrio. Cerchio« für Violine solo (2015) UA/Kompositionsauftrag des SWR 20‘ Helmut Lachenmann Streichtrio (1966) 10‘ Freitag, 13. November 2015, 20 Uhr Theaterhaus Stuttgart, T1 Lisa Streich Helmut Lachenmann »NEBENSONNEN (für Helmut Lachenmann)« »Toccatina« für Klarinette, Violine, Viola und Violoncello (2015) Studie für Violine allein (1986) 6‘ UA/Kompositionsauftrag des SWR 11‘ PAUSE Mark Andre »S2« Helmut Lachenmann »Trio fluido« für Schlagzeug (2015) für Klarinette, Viola und Schlagzeug (1966) 16‘ UA/Kompositionsauftrag des SWR 12‘ Malte Giesen Im Gespräch mit Mark Andre, Helmut Lachenmann und »Stilisierung, mit explosions« Oliver Schneller (Moderation: Björn Gottstein) für Kontrabassklarinette, Schlagzeug, Viola und Elektronik (2015) UA/Kompositionsauftrag des SWR 13‘ Luigi Nono »Sarà dolce tacere« PAUSE Christoph Delz Canto per 8 soli da »La terra la morte« di Cesare Pavese (1960) 10‘ »Arbeitslieder«, op. 8 Oliver Schneller für Tenor, vier falsettierende Bässe, gemischten Chor, »Kireji« Klavier (mit Verstärkung) und Bläserquintett (1983/84) 27‘ für Vokalensemble und Lautsprecher (2015) UA/Kompositionsauftrag des SWR 9‘ Marco Fusi, Violine ensemble recherche Marco Fusi, Violine Florian Hölscher, Klavier Christian Dierstein, Schlagzeug Stuttgart Winds Schola Heidelberg SWR Vokalensemble Dirigent: Walter Nußbaum Dirigent: Marcus Creed Mit freundlicher Unterstützung der Stiftung Christoph Delz 2 3 Samstag, 14. November 2015, 20 Uhr Theaterhaus Stuttgart, T1 Samstag, 14. November 2015, 20 Uhr Theaterhaus Stuttgart, T1 ESSAY Einführung: 19 Uhr, Glashaus Nicolaus A. -

JP Thesis September 09

The Extended Flautist: Techniques, Technologies and Performer Perceptions in Music for Flute and Electronics Author Penny, Margaret Jean Published 2009 Thesis Type Thesis (Professional Doctorate) School Queensland Conservatorium of Music DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/3188 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/366551 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au THE EXTENDED FLAUTIST: Techniques, technologies and performer perceptions in music for flute and electronics Jean Penny Bachelor of Music (Instrumental performance, Honours), University of Melbourne Queensland Conservatorium Griffith University A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance) May 2009 The Extended Flautist KEYWORDS Breath tone, Burt, electronics, contemporary music performance, extended techniques, flute, Hajdu, identity, interactive live electronics, Lavista, meta- instrument, micro-sounds, Musgrave, performance, performance analysis, performance practice, performance space, physicality, Pinkston, Risset, Saariaho, Stroppa, self-perception, sonority, sound technologist, spatialisation, technology. i The Extended Flautist ABSTRACT As musical and performance practices have evolved over the last half-century, the realm of the solo flautist has expanded to encompass an extensive array of emerging techniques and technologies. This research examines the impact