Edinburgh Research Explorer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MEDIA FACTSHEET (15 Mar 2013) Singapore Unveils 320 Hours of Comedies, Entertainment Programmes and Documentaries at Hong Kong I

MEDIA FACTSHEET (15 Mar 2013) Singapore unveils 320 hours of comedies, entertainment programmes and documentaries at Hong Kong International Film & TV Market (FILMART) The Media Development Authority of Singapore (MDA) will lead 37 Singapore media companies to the 17th edition of the Hong Kong International Film & TV Market (FILMART) where they will meet with producers, distributors and investors to promote their content, negotiate deals and network with key industry players from 18 to 21 March 2013. More than 320 hours of locally-produced content including films and TV programmes will be showcased at the 90-square-metre Singapore Pavilion at the Hong Kong Convention & Exhibition Centre (booth 1A-D01, Hong Kong Convention & Exhibition Centre Level 1, Hall 1A). The content line-up includes recent locally-released film comedies Ah Boys to Men and Ah Boys to Men 2, about recruits in the Singapore military directed by prolific Singapore director Jack Neo; Taxi! Taxi!, inspired by a true story of a retrenched microbiology scientist who turns to taxi driving; Red Numbers by first-time director Dominic Ow about a guy who has three lucky minutes in his miserable life according to a Chinese geomancer; and The Wedding Diary II, the sequel to The Wedding Diary, which depicts life after marriage. Also on show are new entertaining lifestyle TV programmes, from New York Festivals nominee Signature, a TV series featuring world-renowned architect Moshe Safdie and singer Stacey Kent; reality-style lifestyle series Threesome covering topics with Asian TV celebrities Utt, Sonia Couling and Nadya Hutagalung; to light-hearted infotainment décor home makeover show Project Dream Home and Style: Check-in, an interactive 360 content fashion lifestyle programme which uses social media to interact with viewers. -

FLM201 Film Genre: Understanding Types of Film (Study Guide)

Course Development Team Head of Programme : Khoo Sim Eng Course Developer(s) : Khoo Sim Eng Technical Writer : Maybel Heng, ETP © 2021 Singapore University of Social Sciences. All rights reserved. No part of this material may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the Educational Technology & Production, Singapore University of Social Sciences. ISBN 978-981-47-6093-5 Educational Technology & Production Singapore University of Social Sciences 463 Clementi Road Singapore 599494 How to cite this Study Guide (MLA): Khoo, Sim Eng. FLM201 Film Genre: Understanding Types of Film (Study Guide). Singapore University of Social Sciences, 2021. Release V1.8 Build S1.0.5, T1.5.21 Table of Contents Table of Contents Course Guide 1. Welcome.................................................................................................................. CG-2 2. Course Description and Aims............................................................................ CG-3 3. Learning Outcomes.............................................................................................. CG-6 4. Learning Material................................................................................................. CG-7 5. Assessment Overview.......................................................................................... CG-8 6. Course Schedule.................................................................................................. CG-10 7. Learning Mode................................................................................................... -

Focus 2016 World Film Market Trends Tendances Du Marché Mondial Du Lm Pages Pub Int Focus 2010:Pub Focus 29/04/10 10:54 Page 1

FOCUS WORLD FILM MARKET TRENDS TENDANCES DU MARCHÉ MONDIAL DU FILM 2016_ focus 2016 World Film Market Trends Tendances du marché mondial du lm Pages Pub int Focus 2010:Pub Focus 29/04/10 10:54 Page 1 ISSN: 1962-4530 Lay-out: Acom*Europe | © 2011, Marché du Film | Printed: Global Rouge, Les Deux-Ponts Imprimé sur papier labélisé issu de forêts gérées durablement. Imprimé sur papier labelisé issu de forêts gérées durablement. Printed on paper from sustainably managed forests. Printed on paper from sustainably managed forests. 2 Editors Martin Kanzler ([email protected]) Julio Talavera Milla ([email protected]) Film Analysts, Department for Information on Markets and Financing, European Audiovisual Observatory Editorial assistants, LUMIERE Database Laura Ene, Valérie Haessig, Gabriela Karandzhulova Lay-out: Acom* Europe © 2016, Marché du Film Printed: Global Rouge, Les Deux-Ponts 2 Editorial As a publication of the Marché du Film, FOCUS FOCUS, une publication du Marché du Film, sera will be an essential reference for professional une référence incontournable pour tous les partici- attendees this year. Not only will it help you grasp pants professionnels cette année. Elle vous aidera the changing practices of the film industry, but it non seulement à appréhender les pratiques en con- also provides specific information on production stante évolution de l’industrie cinématographique, and distribution around the world. mais elle vous informera également de manière plus spécifique sur les secteurs de la production Once again, we are glad to collaborate with et de la distribution dans le monde entier. Susanne Nikoltchev and her team. With this part- nership, we aim to provide you with valuable Nous avons le plaisir de collaborer de nouveau insight into the world of film market trends. -

Film & Media Studies

NGEE ANN POLY 2021 SCHOOL OF FILM & MEDIA STUDIES Film, Sound & Video Mass Communication Media Post- Production xplore xcite xcel School of Your heart’s set on a career in the film or media business. You Film & Media Studies desire to tell the stories that go unheard. You have the passion to make a difference where it matters. All you need is the head 7 Film, Sound & Video (N82) start to take you places. Begin your journey at Singapore’s first and most established film and media school. 11 Mass Communication (N67) 15 Media Post-Production (N13) Want to know what our FMS STORIES– students are capable of THE ONES YOU TELL, creating? Check out some of their outstanding student AND THE ONES THAT SELL projects here: At Ngee Ann Polytechnic’s School of Film & Media Studies (FMS), you learn to tell and sell these stories well. As future filmmakers and media professionals, our Film, Sound & Video (FSV), Mass Communication (MCM) and Media Post-Production (MPP) students learn to craft stories and produce content that are original, compelling and thought-provoking. There is no better way to engage with a global audience that is being bombarded with ever more choices of information, education and entertainment. It’s a tall order, but this is the story of Singapore’s most established film and media school. The FMS faculty is lauded for creating innovative platforms for realistic learning, industry mentorship, entrepreneurship and service learning. With its well-equipped studio and soundstage spaces, you can expect a top-notch learning environment that inspires industry-standard works. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 29 August 2014 – for the 11Th Edition of Its Annual Must-See Musical Pantomime, W!LD RICE Is Looking To

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 29 August 2014 – For the 11th edition of its annual must-see musical pantomime, W!LD RICE is looking to the East for inspiration. Monkey Goes West is based on endearing Chinese fantasy classic Journey To The West , as affectionately re-imagined and relocated to modern-day Singapore by W!LD RICE's Resident Playwright Alfian Sa'at. Acclaimed music composer Elaine Chan will compose a brand-new score for the production. “We've always prided ourselves on taking well-loved fairy-tales and giving them a distinctly local twist,” explains Ivan Heng, Artistic Director of W!LD RICE. “We felt that it was time to explore the wealth of literature and adventure available to us from sources closer to home.” Monkey Goes West marks Broadway Beng Sebastian Tan's directing debut with W!LD RICE. No stranger to the W!LD RICE pantomime, Tan has won great acclaim for playing the evil witch in two previous productions ( Snow White & the Seven Dwarfs and Hansel & Gretel ). He is thrilled to be taking on the role of director for Monkey Goes West . “I wanted it to be based on Tripitaka's Journey To The West because, as a kid, this epic story captured so much of my imagination,” says Tan. “We want to bring audiences on a funny, fabulous, fantastical journey!' 1 The elaborate costumes for the pantomime will be designed by Saksit Pisalasupongs and Phisit Jongnarangsin of Tube Gallery, an award-winning design and fashion company based in Bangkok. Singaporeans have seen their work onstage before: 881 The Musical , The Crucible and Glass Anatomy . -

Media Release Mm2 Asia Invites

mm2 Asia Ltd. Co. Reg. No.: 201424372N 1002 Jalan Bukit Merah #07-11 Singapore 159456 www.mm2asia.com MEDIA RELEASE MM2 ASIA INVITES SHAREHOLDERS TO CELEBRATE SG50 WITH SPECIAL SCREENING OF “7 LETTERS” SINGAPORE, 4 August 2015 – mm2 Asia Ltd. (“mm2 Asia” and together with its subsidiaries, the “Group”), is pleased to invite its mm2 Red Carpet Club members to a special screening of ‘7 Letters’, a unique film to commemorate Singapore’s Golden Jubilee (“SG50”) this year. The Group is proud to be the exclusive worldwide distributor for ‘7 Letters’, an anthology of seven short films directed by Singapore’s seven most illustrious directors – Eric Khoo, Boo Junfeng, Jack Neo, Kelvin Tong, K Rajagopal, Tan Pin Pin, and Royston Tan. The seven directors gathered their creative storytelling and filmmaking talents to present an emotive anthology showcasing the lives and stories of Singaporeans. 1 | P a g e The seven short films are genuine and venerating ‘love letters’ to Singapore, capturing each director’s personal and poignant connection with the place they call home. The seven stories tell of Singapore’s heartland and its people through spellbinding tales of lost love, identity, inter- generational familial bonds, unlikely neighbours, and traditional folklore. ‘7 Letters’ is fully supported by the Singapore Film Commission (“SFC”). “As part of the Red Carpet Club’s activities, we are pleased to invite our shareholders to see ‘7 Letters’, one of this year’s most significant and meaningful films,” said Mr Melvin Ang (洪伟才), CEO of mm2 Asia. “We support local filmmaking, especially films with a special connection to Singaporeans.” Since launching the mm2 Red Carpet Club this year, mm2 Asia organised a series of screenings for its members, including ‘Ah Boys to Men 3: Frogmen’, a co-production by the Group that became the highest grossing opening weekend Asian film in Singapore of all time. -

Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong's National Day Rally 2012 (Speech in English) �Page 1 of 10

Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong's National Day Rally 2012 (Speech in English) Page 1 of 10 Singapore Gcvernr rrt integrity • Service • Car ' .ce -Contact Info fnedback Horne About t,overnniet Monte,, Media Centre >, Prime Minister Recent News -70 Print (pit I OS JUNE 2013 Statement from the Prime Minister's PRIME MINISTER LEE HSIEN LOONG'S NATIONAL Office DAY RALLY 2012 (SPEECH IN ENGLISH) 03 JUNE 2013 MFA Press Statement: Official Visit to Singapore by Prime Minister and Minister of Defence & Security of the "A Home With Hope and Heart" Deinocratic Republic of TimobLeste, 3 - 5 June 2013 Friends and fellow Singaporeans 31 MAY 2013 We have travelled from Third World to First. You know the Singapore story to date well. Our MFA Press Statement: Visit of the question is what is the next chapter of this story? Where do we want Singapore to be 20 years Prime Minister of the Socialist from now? Republic of Vietnam ; His Excellency Nguyen Tan Dung. 31 May to 1 June The next 20 years will see many changes in the world. The first big question will be: will there be 2013 peace or instability in the world, and in Asia? If it is not peaceful, if there are tensions, then we must brace ourselves for a rough ride. But if there is peace and prosperity worldwide, which looks likely, then it is going to be an exciting era of rapid progress and dramatic change. We are both a country and a city. So when we look forward into our future, we have to see our future against what other countries are doing and also against what other cities are doing in the world. -

Issue 6 | December 2013

ISSUE 6 | DECEMBER 2013 Live Together It’s fun for all ages at HDB’s Welcome Parties! LIVE TOGETHER LIVE WELL MY LIFE STORY 2 Making Learning Fun 8 A Walk to 18 From the Block to Remember the Big Screen HDB Issue 06 Cover and back V6.indd 3 11/22/13 5:11 PM Live TOGETHER Contents Live TOGETHER 2 Making Learning Fun 4 A Trip Back in Time Live WELL 6 One Park Fits All 8 A Walk to Remember Live HAPPY Making 10 Going Full Circle 11 Crime Watchers 12 A Chance to Shine learning fu n At HDB’s Outreach to Young Live GREEN and Youth (OHYAY!) roadshows, 14 Engaging and Educational students learn how to be a 16 Reusable Solutions good neighbour through games and quizzes. My LIFE STORY group of “aliens” landed at Red 18 From the Block to the Swastika School on 14 August 2013 Big Screen — however, their agenda was not A Wilson Pang world domination, but to teach students how to be good and eco-friendly neighbours. Known as the HeartlanD ; Photos Beanies, these ‘extraterrestrial’ visitors are part of an animated video presentation G featured in HDB’s Outreach to Young and Gene Khor Youth (OHYAY!) roadshow. Launchednched Text in November 2009, thee OHYAY! roadshows aimm toto share HDB’s communityty goalsgoals with the youths, and engagengage and nurture them in Life Storeys is a twice-yearly publication by the building community bondsnds Housing and Development Board. Filled with lifestyle features, this newsletter features stories and in the heartlands. To date,e, happenings from your neighbourhood so that you the programme has reachedhed can know your community a little better and play out to around 103,000 a more active role in community-building. -

Filmart Ad Cover Day 2.Indd

TUESDAY, MARCH 20 2018 DAY 2 AT FILMART www.ScreenDaily.com Stand 1A-B19 Editorial +852 2582 8958 Advertising +1 213 447 5120 TUESDAY, MARCH 20 2018 TODAY DAY 2 AT FILMART Girls Always Happy, review, p8 REVIEW www.ScreenDaily.com Stand 1A-B19 Editorial +852 2582 8958 Advertising +1 213 447 5120 Girls Always Happy Chinese debut lays bare a complex mother-daughter relationship Jack Neo » Page 8 iQiyi launches dramatic FEATURE heads mm2’s Korea hot projects The latest work from the directors gala slate of Inside Men, The Throne and push as TV series travel The Whistleblower BY SILVIA WONG » Page 12 Celebrating its 10th anniversary, BY LIZ SHACKLETON Hsieh Hsin-ying (Love At Seventeen) Burning Ice, as well as Youku’s Day Singapore’s mm2 Entertainment Chinese streaming giant iQiyi is star in Meet Me @ 1006, which fol- And Night. iQiyi has also sold SCREENINGS presents an extended slate of 24 launching four new series at lows a lawyer who fi nds a strange shows to US platform Dramafever, What’s on at Filmart regional fi lms at Filmart, including Filmart today, tapping into the woman in his apartment at the Korea’s CJ E&M, Malaysia’s Astro, » Page 30 a trio of new titles co-produced trend for Chinese-language TV same time every night, while Jasper Singapore’s StarHub and Hong with Turner Asia Pacifi c. drama to fi nd an audience overseas. Liu (When I See You Again) stars in Kong’s TVB. Taking the spotlight is Killer Not The four 24x45-minute series — Plant Goddess about a music execu- “In the past, costume dramas Stupid, Jack Neo’s fi rst fi lm set out- Meet Me @ 1006, Befriend, Plant tive stranded in a rural village. -

Irene Ang 洪爱玲 Actor

IRENE ANG 洪爱玲 ACTOR. HOST. COMEDIAN. MOTIVATIONAL SPEAKER. JUDGE. DIRECTOR. Ethnicity: Chinese Nationality: Singaporean Height: 1.72m Hair: Black Eyes: Black Languages Spoken: English, Mandarin, Chinese Dialects Irene Ang @flyirene @flyierene Irene Ang’s Showreel Curriculum Vitae Awards Year Title Category Best Comedy Performance by an Actor / Actress 2014 Asian Televsion Awards (Soo Ling in Spouse for House Season 1) 2014 Asian Television Awards Best Comedy Program (Spouse for House) 2012 M:Idea Youth Choice (MCYS) Most Awesome Personality I Wanna Be BFF With Singapore Entertainment Awards, Singapore 2011 Contributions to the Movie Industry Press Holdings Limited The Singapore Women’s Weekly Magazine 2010 Great Women of Our Time – Arts & Media Winner Great Women of Our Time 2008 The Execcutive Magazine Top 25 Most Powerful Businesswomen Singaporeans Going Bananas Survey 2007 Top Bananarina Starbucks Singapore Singapore Publishing Holdings – The New Paper 2007 1st Runner Up Fame Awards 2006 Harper’s Bazaar The Entertainer Extraordinaire 2005 Mediacorp Publishing 8 Days Readers’ Poll Favourite Comedian: Side Splitter 2005 Mediacorp Publishing 8 Days Readers’ Poll Best Makeover: Hey Presto 2004 Ernst & Young Singapore Entrepreneur of the Year Awards Nominee 2003 Spirit of Enterprise Honouree Best Comedy Performance by an Actress 2002 Asian Television Awards (Rosie Phua in Phua Chu Kang Pte Ltd) Highly Recoemmended Best Performance by an Actress (Comedy) 2000 - 02 Asian Television Awards (Rosie Phua in Phua Chu Kang Pte Ltd) 1998 - 03 Asian -

Benjamin Kheng 金文明 Actor

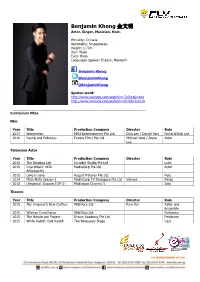

Benjamin Kheng 金文明 Actor. Singer. Musician. Host. Ethnicity: Chinese Nationality: Singaporean Height: 1.73m Hair: Black Eyes: Black Languages Spoken: English, Mandarin Benjamin Kheng @benjaminKheng @BenjaminKheng Spoken word: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TxJNrg2n4o4 http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BhHAV1z4v28 _____________________________________________________________________ Curriculum Vitae Film Year Title Production Company Director Role 2017 Wonderboy MM2 Entertainment Pte Ltd Dick Lee / Daniel Yam Richard/Dick Lee 2016 Young and Fabulous Encore Films Pte Ltd Michael Woo / Joyce Actor Lee Television Actor Year Title Production Company Director Role 2016 The Breakup List Invisible Studio Pte Ltd Luke 2015 Interstitials: HDB MediaCorp Pte Ltd Actor Affordability 2015 Love is Love August Pictures Pte Ltd Pete 2014 Mata Mata Season 2 MediaCorp TV Singapore Pte Ltd Various Ringo 2013 Unnatural (Season 3 EP 2) Mediacorp Channel 5 Jake Theatre Year Title Production Company Director Role 2015 The Emperor’s New Clothes Wild Rice Ltd Pam Oei Tailor and Ensemble 2015 Wildrice Fund Raiser Wild Rice Ltd Performer 2015 The Henderson Project Dream Academy Pte Ltd Performer 2015 White Rabbit, Red Rabbit The Necessary Stage Cast 2014 Ah Boys To Men Musical Running Into The Sun Beatrice Chia Ken Chow Richmond 2013 Edges The Musical Sight Lines Productions Derrick Chew (Various Roles) 2012 National Broadway Company Theatreworks Ong Keng Sen (Dick Lee) 2012 Boom Sight Lines Productions Derrick Chew Young Father, Property Agent 2011 Unleashed! 2011 -

Singaporean Cinema in the 21St Century: Screening Nostalgia

SINGAPOREAN CINEMA IN THE 21ST CENTURY: SCREENING NOSTALGIA LEE WEI YING (B.A.(Hons.), NUS) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF CHINESE STUDIES NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2013 Declaration i Acknowledgement First and utmost, I owe a huge debt of gratitude to my supervisor, Dr. Nicolai Volland for his guidance, patience and support throughout my period of study. My heartfelt appreciation goes also to Associate Professor Yung Sai Shing who not only inspired and led me to learn more about myself and my own country with his most enlightening advice and guidance but also shared his invaluable resources with me so readily. Thanks also to Dr. Xu Lanjun, Associate Professor Ong Chang Woei, Associate Professor Wong Sin Kiong and many other teachers from the NUS Chinese Studies Department for all the encouragement and suggestions given in relation to the writing of this thesis. To Professor Paul Pickowicz, Professor Wendy Larson, Professor Meaghan Morris and Professor Wang Ban for offering their professional opinions during my course of research. And, of course, Su Zhangkai who shared with me generously his impressive collection of films and magazines. Not forgetting Ms Quek Geok Hong, Mdm Fong Yoke Chan and Mdm Kwong Ai Wah for always being there to lend me a helping hand. I am also much indebted to National University of Singapore, for providing me with a wonderful environment to learn and grow and also awarding me the research scholarship and conference funding during the two years of study. In NUS, I also got to know many great friends whom I like to express my sincere thanks to for making this endeavor of mine less treacherous with their kind help, moral support, care and company.