PDF Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Metta Bhavanabhavana Loving-Kindnessloving-Kindness Meditationmeditation Ven

MettaMetta BhavanaBhavana Loving-kindnessLoving-kindness MeditationMeditation Ven. Dhammarakkhita HAN DD ET U 'S B B O RY eOK LIBRA E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.buddhanet.net Buddha Dharma Education Association Inc. Metta Bhavana Loving-kindness Meditation Venerable Dhammarakkhita Published for free dist ribution 974–344–130–1 First edition , copies August Enquiries: Ms. Savanraya Vipatayotin (Nay) Dhammodaya Meditation Centre / Mu Tambol Th anon — Khat Ampur Muang, Nakhon Pathom , Th ailand Tel. (-) . Fax. (-) Website: http//www.rissir.com/dhammodaya E-mail: [email protected] Cover design by Dhammarakkhita with technical assistance from Khun Sangthong Srikaewpraphan Metta Bhavana Loving-kindness Meditation Venerable Dhammarakkhita Venerable Dhammarakkhita is an Australian Buddhist Monk of the Myanmar Th eravada tradition. He has been a monk for about eight years. After extensive and intensive practice in vipassana-mindfulness/insight meditation in Australia and Myanmar, his teacher Venerable Chanmyay Sayadaw instructed him to teach vipassana in Myanmar, Singapore and East and West Malaysia. Venerable Dhammarakkhita spent three years successfully establishing a monastery in South Africa. Th ese days he teaches by invitation in Myanmar, Japan and Th ailand and gives talks wherever he goes. “If you truly love yourself, you’ll easily love another; If you truly love yourself, you’ll never harm another.” Introduct ion Th is short explanation on how to practise Metta Bhavana or Loving -kindness Meditation was given as a three-day week- end retreat at Dhammodaya Meditation Centre in Nakhon Pathom in Th ailand. Mae-chee Boonyanandi, a Th ai Buddhist nun, has invited Venerable Chanmyay Saya daw of Myanmar to be the patron of the Centre. -

Sample Scripts for Using Puppets to Talk with Children About Feelings

Sample Scripts for Puppets and Teachers Talking with Children During the Coronavirus In these 6 video clips with the Incredible Years puppets, Carolyn Webster-Stratton the developer of the Incredible Years programs talks to the child puppets about their feelings. She encourages the child puppets to share their feelings in response to the Covid-19 virus and helps them remember times when they have felt nervous or lonely or afraid in the past and how they have learned to cope with those uncomfortable feelings in order to feel safe, less bored, patient, fair, less lonely and brave. Teachers can share these video clips with other children and by pausing the clip when the puppet is talking about particular uncomfortable feelings such as boredom, nervousness, unfairness, loneliness, and feeling unsafe. When the child puppet shares ways to cope with these feelings the teacher can encourage their students to share their solutions for ways they can think and behave to feel better. Teachers and parents may also watch these vignettes to learn ways they can use puppets themselves with their children to address their specific feelings. Since children ages 4-8 years are cognitively in what Piaget calls the pre-operational stage of cognitive brain development, the use of pretend and imaginative play can be a powerful way of helping children to talk about their feelings and for learning ways to not only manage any uncomfortable feelings but also ways to manage their behavior responses in healthy ways. Hot Tip: With puppets you can open the door to helping children talk about their feelings or to write stories about or draw pictures about their experiences. -

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: DIFFERENCE AMONGST YOUR OWN: THE LIVED EXPERIENCES OF LOW-INCOME AFRICAN- AMERICAN STUDENTS AND THEIR ENCOUNTERS WITH CLASS WITHIN ELITE HISTORICALLY BLACK COLLEGE (HBCU) ENVIRONMENTS Steve Derrick Mobley, Jr. Doctor of Philosophy, 2015 Dissertation directed by: Professor Noah D. Drezner, Department of Counseling, Higher Education, and Special Education Professor Francine H. Hultgren, Department of Teaching and Learning, Policy and Leadership The subtle and deeply impactful nuances of Black intra-racial social class differences that manifest amongst students who attend historically Black colleges (HBCU) has remained untouched and understudied in higher-education scholarship. In this phenomenological study, I explore how low-income African-American students encounter social class within elite HBCU environments. The men and women in this study graduated between the years of 2001 and 2010. Contemporary HBCU student experiences are underscored and reveal great tension between self, community, and place. The philosophical works of Martin Heidegger, Hans-Georg Gadamer and Edward Casey are joined with the voices of Black scholars including W.E.B. DuBois, Audre Lorde, Frantz Fanon, bell hooks, and Toni Morrison to provide critical context for the phenomenon being studied. Max van Manen’s key phenomenological insights also provide a methodological foundation for the study. My co-researchers encountered significant shifts and evolved within their oppressed identities during their undergraduate years. During their undergraduate years they felt a difference amongst their own that they still reconcile today. The participants within this study endured feelings of alienation, wonder, and even confusion within their distinct higher education environments. This study concludes with phenomenological insights for myriad educational stakeholders that include higher educational researchers, higher education practitioners, families, and students. -

People Buy You: the Real Secret to What Matters Most in Business

Table of Contents Praise Title Page Copyright Page Dedication Foreword About the Author Chapter 1 - From Information to Empathy The Light Bulb Goes Off Twenty-First Century Trends Meet Tim Sanders A New Paradigm—from Information to Empathy What’s the Point? Chapter 2 - Friends Buy from Friends and Other Urban Myths Myth #1: Friends Buy from Friends Myth #2: People Buy from People They Like Myth #3: You Have to Sell Yourself People Buy You The Five Levers of People Buy You Chapter 3 - Be Likable Likability Is the Gateway to Connections How to Be Likable Likable Behaviors Be Polite, Nice, Respectful, and Mind Your Manners Be Nice Compliment Others Be Respectful Be There Be Enthusiastic and Confident Invest in Yourself Authenticity Turning First Impressions into Lasting Impressions Summary Chapter 4 - Connect Real Connections The Problem with Rapport The Real Secret to Connecting Ask Questions Be Prepared Listening Keep Them Talking Staying Connected Summary Chapter 5 - Solve Problems The Problem with Pump and Dump The Conflict of Objectives Five Rules of Questioning Empathy and Problem Solving Look Out for Icebergs The Transition from Connecting to Problem Solving About Questions Overcoming Questioning Roadblocks Connecting the Dots Summary Chapter 6 - Build Trust A Foundation of Trust Status Quo Is King You Are Always on Stage Going the Extra Mile Sweat the Small Stuff Leverage Your Support Team Response Admit When You Are Wrong and Apologize Listening Builds Trust Consistent Behavior Summary Chapter 7 - Create Positive Emotional Experiences The Law of Reciprocity Anchoring It Don’t Cost Nuthin’ to Be Nice (Little Things Are Big Things) Develop a Disciplined System Summary Chapter 8 - A Brand Called You “A Brand Called You” Building a Personal Brand Interpersonal Relationships Manage Labels Manage Your Professional Image Become an Expert Managing Your Brand Online Is Not Difficult but It Does Take Vigilance Attack Yourself Praise for People Buy You “People Buy You is not just a self-evident truth, it’s your opportunity to discover why and how. -

Tasar Designer: F.D.Bethwaite, Assisted by I.B.Bruce

Tasar Designer: F.D.Bethwaite, assisted by I.B.Bruce Dimensions Length, Overall 14’10” 4.52m Length, Waterline 14’00” 4.27m Beam 5’9” 1.75m Hull Depth 2’½” 0.62m Sail Area: Main 90sq.ft. 8.36sq.m. Jib 33sq.ft. 3.07sq.m. Sailing the Tasar By Frank Bethwaite And Ian Bruce Introduction This manual has been written for the sole purpose of helping you to enjoy your Tasar to the fullest, regardless of your previous skills and experience. Section I shows you how to assemble and rig your Tasar. Section II deals with the basics of handling, sailing and maintaining your boat and is in tended primarily for those who have had limited experience with a light, planing sailboat. If you already have dinghy experience you will find Section II pretty simple stuff but we still recommend that you breeze through it as one or two points are peculiar to the Tasar. Once you and your crew are comfortable with the boat and confident in your ability to handle it afloat and ashore, it follows, inevitably, that you will seek to increase your knowledge because with it will come increased pleasure. In Section III we let you delve into the principles behind the evolution and design of the Tasar and, in particular, help you to more fully understand the importance of the over-rotating mast by reintroducing you to the basic aerodynamic principles of sails and sail shapes. Section IV is a detailed look at the upwind performance of the Tasar and the infinite control which can be exercised over the full spectrum of wind conditions. -

A Brief Cognitive Behavioural Intervention for Regular Amphetamine Users- 2 Posted 26/02/08

A brief cognitive behavioural intervention for regular amphetamine users A treatment guide © University of Newcastle 2003 ISBN 1-74186-503-4 Online ISBN 1-74186-504-2 Copyright in this work is retained by the University of Newcastle. Full rights to use, sub-licence, reproduce, modify and exploit the work are granted by the University of Newcastle to the Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. Permission to use this work beyond the limits or for purposes other than those permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 (Commonwealth), must be obtained from the Department of Health and Ageing. Publication approval number 3013 This guide is based on an intervention developed by Baker, A., Kay-Lambkin, F., Lee, N.K. & Claire, M., and was adapted from the sources cited in the ‘Sources and Acknowledgements’ Section of this guide. This project was funded by the Illicit Drugs Section, Drug Strategy Branch, Population Health Division, Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. This guide was prepared by Linda Jenner and Frances Kay-Lambkin on behalf of the study group. Suggested Citation: Baker, A., Kay-Lambkin, F., Lee, N.K., Claire, M. & Jenner, L. (2003). A Brief Cognitive Behavioural Intervention for Regular Amphetamine Users. Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. The opinions expressed in this document are those of the authors and are not necessarily those of the Australian Government. Publications Production Unit Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing ii "#3*&'$0(/*5*7&#&)"7*063"-*/5&37&/5*0/'033&(6-"3".1)&5".*/&64&34r"53&"5.&/5(6*%& Contents BACKGROUND 1 SECTION 1. -

A Study of the Book of Ruth

A Study of the Book of Ruth by Becky J. Case & Allyson M. Barrante For: Crux Bible Study Leaders Crux Bible Study is a Geneva College Community Bible Study Sponsored by the Staff of The Coalition for Christian Outreach and “The Call” Fall 2004 Dear Crux Bible Study Leaders, Welcome to the study of the book of Ruth. It’s with great excitement and eager expectation that we begin this study. This beautiful and eloquently written story is packed with truth about God and His workings in the ordinary circumstances of life. Our prayer is that as you dig into the Scriptures with a group of peers here at Geneva College that your lives will be transformed in new ways. Our hope is that this guide will be a helpful resource to you, and aid in developing your gifts as a small group leader while giving a clearer picture of the Word to students in your study. A few thoughts as you begin this journey: The Crux Bible study guide has been designed to be just that: a guide. Our desire is for you to develop it further, make changes that adapt it to your group, and make choices about how to use the questions we’ve developed. The last thing this guide has been prepared for is to make the job of the small group leader “easy”. Rather, it has been made to help create informed leaders. The book of Ruth is a beautiful story, and probably one you may have heard in Sunday School as a child. While we admire the creativity of our God to reveal himself through a variety of means, we must be careful to remember it is far more than an eloquently written love drama. -

Your Pregnancy Guide IMPORTANT CONTACTS

Your Pregnancy Guide IMPORTANT CONTACTS FILL IN THIS INFORMATION SO YOU HAVE IT WHEN YOU NEED IT. Healthcare Provider Phone Address City After Hours Phone Hospital Phone Address Health Department Phone Address Maternity Care Coordinator Phone In Case of Emergency, Contact: Name Phone Name Phone MY PRENATAL APPOINTMENTS USE THIS SPACE TO WRITE DOWN YOUR PRENATAL APPOINTMENTS. WEEK DATE TIME WEEK DATE TIME 1 to 4 33 to 34 5 to 8 35 to 36 9 to 12 37 13 to 16 38 17 to 20 39 21 to 24 Due Date ? 25 to 28 40 29 to 30 41 31 to 32 42 If you can’t keep an Childbirth Class Date: Time: appointment, Breastfeeding Class Date: Time: remember to RESCHEDULE. My Postpartum Visit Date: Time: CONGRATULATIONS! You are going to be a mother! You may feel like you have no control over what’s happening to your body and emotions anymore. But you do! What you do during your pregnancy will make a difference. It’s important to take care of yourself physically and emotionally. The more you know about what’s happening and the more you let others know how you feel, the more in control you will be. This book answers lots of questions pregnant women ask. But remember, every pregnancy is different. Even if you’ve been pregnant before, this pregnancy can be very different. When you are pregnant, you will have many prenatal appointments with your healthcare providers. Prenatal is a term that refers to when you are pregnant. Pre = before and natal = birth. -

Manage Stress Workbook

Manage Stress workbook U.S. Department of Veterans Aairs Veterans Health Administration Patient Care Services Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Contents Stress Goal 1 This workbook was designed by the National Keys to Managing Your Stress 2 Center for Health Promotion and Disease Tools for Managing Stress 4 Prevention (NCP). It will guide you through Mindfulness 7 steps to identify and track your stress, and practice a variety of strategies that have been Other Factors for Managing Stress 13 shown to counteract stress. Appendix A: My Health Choices 15 Appendix B: Pleasant Activities Tip Sheet 17 It goes without saying that you have probably experienced periods of high stress and danger. You probably are well acquainted with the depression, aggressive behavior, and low energy ‘fight or flight’ feeling that often occurs in such are other common symptoms. situations. This heightened feeling occurs when our bodies release stress hormones in response You can learn specific techniques for managing to the stress. The hormones keep us alert and your stress more effectively. These techniques ready to deal with whatever is happening or is can help you lower your stress and improve about to happen. your readiness to respond in stressful situations. You’ll also deal more easily with While this natural response serves us well in stress when it comes up. the short term, our bodies need time to recover. Prolonged, high stress can cause high blood It’s important to remember that you cannot pressure, a weakened immune system, heart always control the causes of your stress, but you disease, and digestive problems. -

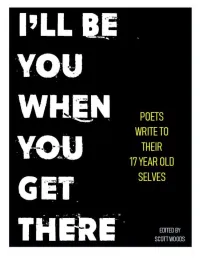

I'll Be You When You Get There

I’ll Be You When You Get There: Poets Write To Their 17 Year Old Selves Collection ©2019 by Scott Woods All individual poems rights remain with their respective authors beyond this one-project usage. Black Air Press Columbus, Ohio Cover art by Scott Woods This book is not for sale. This is an act of charity and community. It is intended as a digital product only. Print-outs of the book are allowed for personal or educational purposes. If you discover that someone is selling this collection in any capacity or form please inform the editor. Upon notice of such a breach, said editor will take a baseball bat to the offending party’s world. So don’t be that guy. Requests for further information or uses may be directed to the editor. To the students of South High School: We’re all rooting for you. Yes, you too. My side of the story is the incomplete side of yours L.R. CONTENTS Steve Brightman But Most Of All, Get Used To The Dust While You Renovate Sidney Jones, Jr. State of The Union Address to a 17 year-old Self Jenise Michele Asking For Her Forgiveness (a poem for Jessica) Tony Brown Clarity Wess Mongo Jolley 20 Pieces of Advice, Sent to My Younger Self, to be Opened June 15, 1978 Ruby Harper I Really Wanted... J. Kennedy Untitled Christina Hoverman 14 Year Hindsight Nancy Kangas Get Out Ryk McIntyre I Sent a Letter to Myself at 17, It Came Back "Return to Sender" Amy Monahan-Curtis The Fall Lee Rossi Instructions to My Teenage Self Matt Mason The Problem Jessica Kahn A Letter to My 17 Year Old Self Justin Lipscomb 17 Branches Won't Hold -

Improving the Social Skills of Children with High-Functioning Autism Spectrum Disorder: an Intervention Study

IMPROVING THE SOCIAL SKILLS OF CHILDREN WITH HIGH-FUNCTIONING AUTISM SPECTRUM DISORDER: AN INTERVENTION STUDY by Cynthia Aileen Waugh A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Applied Psychology and Human Development Ontario Institute for Studies in Education University of Toronto © Copyright by Cynthia Waugh 2015 Improving the Social Skills of Children with High-Functioning Autism Spectrum Disorder: An Intervention Study Cynthia A. Waugh Doctor of Philosophy Department of Applied Psychology and Human Development Ontario Institute for Studies in Education University of Toronto 2015 Abstract Previous research has found that although most children with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder (HFASD) desire friendship, they have fewer and less stable friendships and report more loneliness than their peers. They also tend to be socially naïve, vulnerable to deception and more often bullied. A significant contributor to their challenges is an impaired Theory of Mind (ToM), which is the ability to reason about mental states (e.g. knowledge, emotions, desires, beliefs, intentions). While social difficulties define ASD, research suggests that visual processing may be a relative strength. This bias favoring visual information over verbal mental representations appears to have enabled some children to gain mental state understanding via the use of visual supports. Since peer acceptance is a powerful predictor of mental health and the risks of peer rejection— and benefits of friendship— extend into adulthood, it is important to teach friendship-making skills. This was the broad objective of the study, which drew upon research demonstrating that ii despite deficits in ToM, children with HFASD have strengths in visual processing which can be utilized to enhance learning. -

Markham Peaceful Parent 6-25-12

! ! DRAFT!COPY! NOT!FOR!CIRCULATION! ! ! ! ! ! Peaceful!Parent,!Happy!Kids How to Stop Yelling and Start Connecting Laura Markham, Ph.D. Praise for Peaceful Parent, Happy Kids Advance Press Review Excerpts Other Parenting Experts’ Review Excerpts Waiting for: Elizabeth Pantley, Patty Wipfler "The Aha! moment in Dr. Laura Markham's Peaceful Parent, Happy Kids is that attachment isn't just for babies. Attachment provides the foundation for the growing child to learn emotional intelligence, empathy, and responsibility while he masters his environment. Dr. Laura teaches by example, holding parents with compassion as she gives them priceless, easy to use strategies to create a secure, healthy attachment with their child.” - Lysa Parker & Barbara Nicholson, Founders of Attachment Parenting International and authors of Attached at the Heart: 8 Proven Parenting Principles for Raising Connected and Compassionate Children. "Dr. Laura shows parents how their empathy can wire their child's brain for emotional regulation and happiness -- and a brighter future for humanity. Her understanding and knowledge of the many challenges of raising loving, compassionate children gives parents powerful tools to be the best that they can be. A simple, yet revolutionary, message of love." - Nancy Samalin, M.S, best selling parenting author whose most recent book is Loving Without Spoiling. Peaceful Parents, Happy Kids has two important ideas, and one revolutionary idea. Dr. Laura Markham’s guidance on fostering connection and coaching instead of controlling are the important ideas, and they can make a huge difference in your life as a parent. Her explanation of why parents need to regulate ourselves first—before we can help regulate our children--is the revolutionary idea.