Dorothy Lichtenstein (Dl)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

United States District Court Eastern District of New York

Case 1:13-cv-06147-PKC-JO Document 115 Filed 09/28/15 Page 1 of 68 PageID #: <pageID> UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK --------------------------------------------------------X CYNTHIA HILL, GAIL WILLIAMS, DENISE INMAN, VICKIE GORDON, ROLANDO LOPEZ, TAURA PATE, ELLEN ENNIS, and ANDREA HOLLY, individually and on behalf of all others similarly situated, Plaintiffs, MEMORANDUM & − against − ORDER 13 CV 6147 (PKC) (JO) THE CITY OF NEW YORK, MICHAEL R. BLOOMBERG, as Mayor of the City of New York, RAYMOND KELLY, as Police Commissioner, RICHARD F. NAPOLITANO, CHARLES P. DOWD, MICHAEL V. POLITO, LJUBOMIR BELUSIC, FRANCIS KELLY, DONALD CHURCH, DAVID LICHTENSTEIN, LOCAL 1549, DISTRICT COUNCIL 37, AFSCME, AFL-CIO, and JOHN and JANE Does 1−20 (said names being fictitious, the persons intended being those who aided and abetted the unlawful conduct of the named Defendant), Defendants. --------------------------------------------------------X PAMELA K. CHEN, United States District Judge: The named Plaintiffs and members of the proposed classes (“Plaintiffs”) are a group of minority individuals employed by Defendant New York City (the “City”) to answer and direct public calls to the City’s 911 emergency response system. (Dkt. 77 (“Am. Compl.”) ¶ 12.) Plaintiffs bring this action against the City; Michael Bloomberg as Mayor of the City and Raymond Kelly as New York Police Department (“NYPD”) Commissioner, both in their official Case 1:13-cv-06147-PKC-JO Document 115 Filed 09/28/15 Page 2 of 68 PageID #: <pageID> capacities1; and Richard F. Napolitano (“Napolitano”), Charles P. Dowd (“Dowd”), Michael V. Polito (“Polito”), Ljubomir Belusic (“Belusic”), Francis Kelly (“Kelly”), Donald Church (“Church”), and David Lichtenstein (“Lichtenstein”), all in their official and individual capacities (collectively, “City Defendants”), primarily asserting that the City Defendants discriminated against Plaintiffs on the basis of race, in violation of 42 U.S.C. -

THERE WILL BE FLOOD Councilman Warns of Storm Dangers to Gowanus Condo Plan by Natalie Musumeci Brad Lander (D–Gowanus)

LOOK FOR BREAKING NEWS EVERY WEEKDAY AT BROOKLYNPAPER.COM Yo u r Neighborhood — Yo u r News® BrooklynPaper.com • (718) 260–2500 • Brooklyn, NY • ©2012 Serving Brownstone Brooklyn and Williamsburg AWP/12 pages • Vol. 35, No. 47 • November 23–29, 2012 • FREE THERE WILL BE FLOOD Councilman warns of storm dangers to Gowanus condo plan By Natalie Musumeci Brad Lander (D–Gowanus). tial development at the site would The Brooklyn Paper “The Lightstone Group is fully put future tenants in danger. The development company committed to the development of “It would be a serious mistake Lightstone Group won’t let Hurri- its Gowanus Canal project in the for you to proceed as though noth- cane Sandy — or an angry coun- Carroll Gardens neighborhood ing had happened, without recon- cilman — stand in the way of its and will move forward to build sidering or altering your plans, plan to construct a massive hous- a high-quality, environmentally and putting over 1,000 new resi- ing complex on the banks of the sound residential complex,” the dents in harm’s way the next time Gowanus Canal. company said in a statement re- an event of this magnitude oc- The real estate firm is marching leased to The Brooklyn Paper. curs,” Lander wrote. ahead with its proposal to build a News that the project will ad- Lightstone Group spokesman controversial 700-unit development vance comes after Lander penned Ethan Geto said his company “vi- on Bond Street between Carroll an open letter to Lightstone Group File photo by Stefano Giovannini olently objects” to the suggestion and Second streets despite severe CEO David Lichtenstein last week The Lightstone Group isn’t backing down from its plan the development would put pro- flooding in the neighborhood and urging the company to drop its to build a 700-unit housing complex on the banks of the spective residents in jeopardy and the vocal opposition of Councilman plans — and claiming a residen- Gowanus Canal. -

Pop Art with Roy Lichtenstein

January 2020 The Studiowith ART HIST RY KIDS Pop Art with Roy Lichtenstein Observe | Discuss | Discover | Create | Connect Pop Art with The Studiowith Roy Lichtenstein ART HIST RY KIDS INTRODUCTION The art of the ordinary Roy Lichtenstein’s successful art career was based on one simple idea – creating fine art inspired by images we see everyday. His art captures the ordinary things that surround us – advertisements, comic books, the painting of other famous artists like Picasso, Mondrian, Matisse, and Monet, and even Micky Mouse cartoons. He took these ideas and recreated them on a larger than life scale. Most of his can- vases are grand and oversized – they are truly bold and impactful when seen in person! He also infused little bits of commentary in his art, and he became known for his skillful use of parody. You don’t need to study every piece of art that’s included in this guide. Feel free to choose just a few that are most interesting to your kids. A range of subject matter is included here, but if some of these paintings are too intense for your kids– just skip them for now, and come back to them when they are older! There’s no hurry, and there are plenty of paintings included here that are perfect for young kids. Pop Art looks out into the world. This is your week to look closely at the “ art and chat about it. We’ll learn all It doesn’t look like a painting of about Lichtenstein and his art next something, it looks like the thing week. -

Roy Lichtenstein, Sociedad Moderna Como Expresión Artística. Rocio Castillo Rojas. “El Pop Art Mira Hacia El Mundo. No Parec

Roy Lichtenstein, sociedad moderna como expresión artística. Rocio Castillo Rojas. “El Pop Art mira hacia el mundo. No parece una pintura de algo, se parece a la cosa en sí misma”1. De esta forma Roy Lichtenstein intentaba responder la pregunta del crítico de arte, G.R. Swenson, ¿Qué es el Pop Art? (1963) y es que para entonces ya se reconocía el valor de sus obras para el enaltecimiento artístico de la sociedad moderna. A fines de los 50, el Pop Art surgía como reacción al Expresionismo Abstracto representando imágenes y elementos de la sociedad moderna caracterizada por el consumismo, los medios de comunicación masivos, la moda, la tecnología, el capitalismo, etc. Sus principales impulsores buscaban convertir la cotidianeidad de la cultura occidental en una obra estética de forma crítica e inteligente, entre ellos destaca la obra de Roy Lichtenstein. Lichtenstein nace en 1923, en Nueva York, EEUU, siendo el primero de dos hijos del matrimonio entre Milton y Beatrice Lichtenstein. Desde joven presentó habilidades artísticas y musicales: dibujaba, pintaba, esculpía, tocaba piano y clarinete, y desarrollo una gran afición por el jazz. El verano de 1940, año en que se graduó de preparatoria, estudió pintura y dibujo en la Art Students League de Nueva York con Reginald Marsh. Ese mismo año ingresó a la Facultad de Educación de la Universidad Estatal de Ohio, pero no fue hasta 1946 que logró graduarse como Bachelor of Fine Art, desde entonces comenzó su carrera como académico en la misma Universidad Estatal de Ohio y en paralelo preparó su maestría la cual obtuvo en 1949. -

Apokalypse--Send.Pdf (1.360Mb)

Apokalypse En analyse av Hariton Pushwagners maleri Jobkill i lys av popkunstens estetikk Linda Ottosen Bekkevold Masteroppgave i kunsthistorie Institutt for idé - og kunsthistorie og klassiske språk UNIVERSITETET I OSLO Høst 2014 II Apokalypse En analyse av Pushwagners maleri Jobkill (1990) i lys av popkunstens estetikk. III © Linda O. Bekkevold 2014 Apokalypse Linda O. Bekkevold http://www.duo.uio.no/ Trykk: Reprosentralen, Universitetet i Oslo IV Sammendrag Pushwagner blir ofte omtalt som popkunstner og Norges svar på Andy Warhol (1923-1987) og Roy Lichtenstein (1923-1997). Sammenligningen begrunnes med hans benyttelse av tegneserieestetikk. Med stiliserte former og fargeflater. Dette er en gjenkjennende karakteristikk av den amerikanske popkunsten klisjéfylte tegneserieuttrykk. Denne oppfatningen nevnes ofte i en bisetning uten at det foreligger noen kunsthistorisk analyse som har undersøkt dette. Pushwagner samarbeidet med den norske forfatteren Axel Jensen (1932- 2002) på 1960-tallet, og sammen skapte de et tegneserieunivers som skulle bli grunnlaget for Pushwagners kunstnerskap. På 1970-tallet og 1980-tallet arbeidet de med flere utkast og upubliserte bokprosjekter som ble utviklet til billedromanen Soft City, silketrykkserien En dag i familien Manns liv og malerifrisen Apokalypse. I denne avhandlingen søker jeg svar på hvordan Pushwagner benytter seg av tegenserieestetikken i sitt kunstuttrykk. Hva slags tradisjon benyttes i hans verk? Og kan man med rette karakterisere Pushwagner som popkunstner? Problemstillingene er verksorientert, og jeg tar utgangspunkt i maleriet Jobkill (1990), men det vil bli trukket paralleller til andre verk av kunstneren. I oppgavens tolkningsdel vil jeg trekke inn komparativt materiale fra popkunsten. V VI VII Forord I 2010-2012 hadde jeg gleden av å jobbe i et av Norges nyoppstartede gallerier, Galleri Pushwagner. -

Commentary of the Five Works Of

ART IN THE ENGLISH SPEAKING WORLD Work of art Commentary Roy Lichtenstein (1923 -1997) Introduction This document is a painting by Roy Lichtenstein, Girl with Ball , 1961 who is an American pop artist. He was a prominent figure in the Pop Art movement (with Andy Warhol, Jasper Johns and others). Pop Art emerged in the 60s, which was a consumerist period in the US. Girl with Ball was painted in 1961 and can be seen at the MOMA Museum in New York City (USA). Description This painting represents a woman who is putting up her arms because she is playing with a ball. Her hair is waving. She must be speaking because her mouth is opened. She seems to have fun. She is on the beach because she is wearing a swimsuit. Everything is typical of the sixties in the US. Besides, the woman is in the foreground but there is no background. She is standing, alone and beautiful, in the middle of the painting. The colours are warm: the basis of the painting is yellow (it must be a sunny day) and the red of the ball reminds us with that of her lips. The colours render a peaceful impression, as if we were on holiday. Analysis Lichtenstein took the image for Girl with Ball from an advert of a lodge for honeymooners, in the Pocono Mountains. He transformed the image with the techniques of the comic-strip artist and printer. This strengthens the artifice of the picture. It shows the stereotypical 50 s American girl (the pin up), with wavy shiny long hair, open mouth with lipstick and a beautiful body. -

Lightstone Launches Tech-Related Real Estate Investment Platform

Lightstone Launches Tech-Related Real Estate Investment Platform https://thediwire.com/lightstone-launches-tech-related-real-estate-investment-platform/ April 11, 2019 Lightstone, a real estate investor, developer and sponsor of alternative direct investments, has launched a new platform to purchase telecommunications and technology real estate assets. With an initial allocation of $300 million, the platform will focus on acquiring existing but underutilized data centers and telecom infrastructure, existing technology-related real estate, and new development opportunities. “As the use of cloud-based data skyrockets and growth of cloud platforms like Amazon and Google continues, there is overwhelming need for large-scale data center facilities that can support these providers and services,” said David Lichtenstein, CEO of Lightstone. “We’ve launched the platform to capitalize on the opportunity to meet this demand.” Lightstone’s platform will focus on both primary and secondary markets, including potential expansion into European markets. The company’s investments will encompass underutilized data center facilities with anchor tenant sales and leasebacks from large enterprise companies, existing technology-related real estate that can support additional leases, and new development opportunities presented by the growth of tech giants and cloud providers. In January 2019, the platform closed on its first development site, acquiring 2175 Martin Avenue in Santa Clara, California. The site will be a three-story, 88,000 square foot data center and is expected to be delivered as soon as early 2021. Christopher Flynn was named president of Lightstone Data Fund and will manage the fund and its technology- based assets. Flynn has more than 20 years of experience in the data real estate sector and a record of building data centers for EdgeConnex in 35 global locations, the company said. -

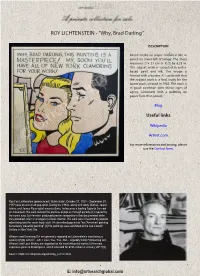

Lichtenstein Why Brad Darling

ROY LICHTENSTEIN - "Why, Brad Darling" DESCRIPTION Mixed media on paper. Initialled (RL) in pencil on lower-left of image. The sheet measures 21x 21 cm or 8.25 by 8.25 in. The subject work is executed in water- based paint and ink. The image is framed with a border. It is probable that the subject work is a final study for the iconic work, created in 1962. The work is in good condition with minor signs of aging, consistent with a painting on paper from that period. Blog Useful links Wikipedia Artnet.com For more information and pricing, please use the Contact form. Roy Fox Lichtenstein (pronounced /ˈlɪktənˌstaɪn/; October 27, 1923 – September 29, 1997) was an American pop artist. During the 1960s, along with Andy Warhol, Jasper Johns, and James Rosenquist among others, he became a leading figure in the new art movement. His work defined the premise of pop art through parody.[2] Inspired by the comic strip, Lichtenstein produced precise compositions that documented while they parodied, often in a tongue-in-cheek manner. His work was influenced by popular advertising and the comic book style. He described pop art as "not 'American' painting but actually industrial painting".[3] His paintings were exhibited at the Leo Castelli Gallery in New York City. Whaam! and Drowning Girl are generally regarded as Lichtenstein's most famous works,[4][5][6] with Oh, Jeff...I Love You, Too...But... arguably third.[7] Drowning Girl, Whaam! and Look Mickey are regarded as his most influential works.[8] His most expensive piece is Masterpiece, which was sold for $165 million in January 2017.[9] Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roy_Lichtenstein E: [email protected]. -

Kirk Varnedoe (Kv)

THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART ORAL HISTORY PROGRAM INTERVIEW WITH: KIRK VARNEDOE (KV) INTERVIEWER: SHARON ZANE (SZ) LOCATION: THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART DATE: 28 NOVEMBER 2001 BEGIN TAPE 1, SIDE 1 SZ: I'll start the way I always do, and ask you to tell me where and when you were born, and something about your family background. KV: I was born in Savannah, Georgia, January 18, 1946. I was the youngest of four children, by a good stretch. My two brothers and my sister were six, seven and eight years older than I was, so I was the baby of the family, by a long shot. My parents had both grown up, more or less, in Savannah, although my father wasn't born there. He was an investment banker who had started his own firm in the depths of the Depression, which was an odd thing to do, but he still, when I was growing up, was running it with a partner, as a private investment firm. SZ: Did you say he was not from Savannah? KV: He was born in Tampa, actually. SZ: Well, he was southern, anyway. KV: Yes, he was southern. Definitely. Southern, and with strong Scottish ties; very proud of his Scottish heritage. He was president of the St. Andrew's Society. I grew up with small kilts, piping in front of the haggis -- that sort of thing. MoMA Archives Oral History: K. Varnedoe page 1 of 180 SZ: Golf? KV: He was a very big golfer. He took us to Glen Eagles and St. -

Hurricane Maria's Battering

The IndypendenT #229: nOVeMBeR 2017 • IndypendenT.ORG ARTS FUndInG FOR The ReST OF US, p4 AMAZOn STALKS The BIG AppLe, p6 FALL MUSIC, p20 ReSISTAnCe & ReSILIenCe In pUeRTO RICO Hurricane Maria COVeRAGe STARTS On pAGe 10 survivors inside their home. CAROLYN COLE/GETTY IMAGES WE REMEMBER. MARCH WE RESIST. ACROSS THE SANDY5TH ANNIVERSARY WE RISE. BROOKLYN SATURDAY OCTOBER 28TH 11AM CADMAN PLAZA, BROOKLYN BRIDGE 2 COMMUNITY CALENDAR The IndypendenT THE INDYPENDENT, INC. 388 Atlantic Avenue, 2nd Floor Brooklyn, NY 11217 212-904-1282 www.indypendent.org Twitter: @TheIndypendent facebook.com/TheIndypendent BOARD OF DIRECTORS: FRI OCT 20 retrospective of Ayón’s work FROM SYRIA Costumes are strongly encour- Ellen Davidson, Anna Gold, 6:30PM • FREE on view at El Museo del Barrio Appearing with journalist and aged. Alina Mogilyanskaya, Ann SCREENING: BLACK PANTHERS: (1230 5th Ave.) until Nov. 5. illustrator Molly Crabapple, DROM Schneider, John Tarleton VANGUARD OF THE REVOLUTION KING JUAN CARLOS I OF SPAIN Wendy Pearlman will discuss 85 Avenue A A fi lm screening and discussion CENTER, AUDITORIUM her new book, which chronicles EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: on the riveting documentary 53 Washington Square South the war in Syria from its origins WED NOV 1 John Tarleton exploring the Black Panther to its present horror through 7:30PM • $30 Party, its signifi cance for black TUE OCT 24 the words of ordinary people. BOOK LAUNCH: MATT TAIBBI ASSOCIATE EDITOR: people and to the broader 7PM–10 PM • FREE BLUESTOCKINGS BOOKSTORE PRESENTS I CAN’T BREATHE: A Peter Rugh American culture and the pain- FORUM: CLIMATE SOLUTIONS 172 Allen St. -

Nicolas Moufarrege: Recognize My Sign Contemporary Arts Museum Houston

Nicolas Moufarrege: Recognize My Sign Contemporary Arts Museum Houston Nicolas Moufarrege: Recognize My Sign November 10, 2018–February 17, 2019 Please do not remove from gallery. 1 Nicolas Moufarrege: Recognize My Sign Contemporary Arts Museum Houston BEIRUT In 1973, Nicolas Moufarrege mounted his first art exhibition at Triad Condas gallery in Beirut, Lebanon. The exhibit included a number of modestly-sized portrait-tapestries; a representative work is included in this exhibition. Moufarrege did not follow pre-made plans when embroidering, as one would with a standard embroidery kit. His approach, which he called “experimental weaving,” is improvisational: as images developed, he elaborated on them stitch by stitch. A similar energy enlivens a nearby drawing in marker on paper. For his tapestries, Moufarrege inventively used a combination of silk, cotton, and wool threads in varying colors to create vibrant textures, movement, and tonal shifts. In a 1973 interview with Moufarrege in the magazine Le Beyrouthin on the occasion of his inaugural show, the noted Lebanese artist Etel Adnan remarked that “this is how traditional craftsmanship becomes a personal art full of promise.” Unless otherwise noted, all works appear courtesy Nabil Moufarrej and Gulnar “Nouna” Mufarrij, Shreveport, Louisiana. No. 7, 1975 Thread on needlepoint canvas Une Ile [An Island], 1975 Thread on needlepoint canvas Please do not remove from gallery. 2 Nicolas Moufarrege: Recognize My Sign Contemporary Arts Museum Houston Embroidered patch, n.d. Thread and bead on denim Artist’s scrapbook, n.d. Various materials Untitled drawing, n.d. Marker on paper Title unknown, n.d. Thread on needlepoint canvas Please do not remove from gallery. -

In This Issue

VOLUME 36 NUMBER 3 NUMBER 36 VOLUME Uniting the Schools of Thought World Organization and Public Education Corporation - National Association for the Advancement of Psychoanalysis STANDING IN THE SAME STREAM: ENVY & JEALOUSY CHALLENGES RIVALS IN AND OUT OF OUR ANALYTIC CIRCLES by Robert Marchesani After waking from a night- Heinz Hartmann and the hapless ego psychologists is main- mare, 25-year-old Leonardo tained at an impressive level.” Da Vinci is told: “You have a gift, Leo, a kind of genius, the The same was true between Anna Freud’s followers and those likes of which I’ve never seen; of Melanie Klein and other schools of rivaling thought about and because of that, people psychoanalysis and psychotherapy. “Freud, the father, doesn’t will always seek to destroy you. escape this either among those who disdain him for his patriar- Please, don’t aid them in their chal and scientistic inclinations, but also the idealized identifica- endeavor.” - Da Vinci’s Demons tions that he inspired,” Lichtenstein continued. “Fixed, absolute identifications and their fiction of wholeness and certainty are Edmund Leites and Symposium 2013 began with ultimately anathema to the vital play of desire. They turn it Martin Bergman David Lichtenstein’s keynote instead into its death form, which is envy.” presentation I Am Not What I Am (a line by Iago from “Othello”) from a qualifying Lacanian “In theater and in literature,” Lichtenstein analyzed, “envy and perspective. Co-founder, faculty member, and supervisor at jealousy are as often the subject of comedy as of tragedy. Après Coup Psychoanalytic Association, Lichtenstein set the This tragi-comic theme is the hatred among rivals.