Kirk Varnedoe (Kv)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Economist Print Edition

The Pop master's highs and lows Nov 26th 2009 From The Economist print edition Andy Warhol is the bellwether The Andy Warhol Foundation $100m-worth of Elvises “EIGHT ELVISES” is a 12-foot painting that has all the virtues of a great Andy Warhol: fame, repetition and the threat of death. The canvas is also awash with the artist’s favourite colour, silver, and dates from a vintage Warhol year, 1963. It did not leave the home of Annibale Berlingieri, a Roman collector, for 40 years, but in autumn 2008 it sold for over $100m in a deal brokered by Philippe Ségalot, the French art consultant. That sale was a world record for Warhol and a benchmark that only four other artists—Pablo Picasso, Jackson Pollock, Willem De Kooning and Gustav Klimt— have ever achieved. Warhol’s oeuvre is huge. It consists of about 10,000 artworks made between 1961, when the artist gave up graphic design, and 1987, when he died suddenly at the age of 58. Most of these are silk-screen paintings portraying anything from Campbell’s soup cans to Jackie Kennedy and Mao Zedong, drag queens and commissioning collectors. Warhol also created “disaster paintings” from newspaper clippings, as well as abstract works such as shadows and oxidations. The paintings come in series of various sizes. There are only 20 “Most Wanted Men” canvases, for example, but about 650 “Flower” paintings. Warhol also made sculpture and many experimental films, which contribute greatly to his legacy as an innovator. The Warhol market is considered the bellwether of post-war and contemporary art for many reasons, including its size and range, its emblematic transactions and the artist’s reputation as a trendsetter. -

The Ronald S. Lauder Collection Selections from the 3Rd Century Bc to the 20Th Century Germany, Austria, and France

000-000-NGRLC-JACKET_EINZEL 01.09.11 10:20 Seite 1 THE RONALD S. LAUDER COLLECTION SELECTIONS FROM THE 3RD CENTURY BC TO THE 20TH CENTURY GERMANY, AUSTRIA, AND FRANCE PRESTEL 001-023-NGRLC-FRONTMATTER 01.09.11 08:52 Seite 1 THE RONALD S. LAUDER COLLECTION 001-023-NGRLC-FRONTMATTER 01.09.11 08:52 Seite 2 001-023-NGRLC-FRONTMATTER 01.09.11 08:52 Seite 3 THE RONALD S. LAUDER COLLECTION SELECTIONS FROM THE 3RD CENTURY BC TO THE 20TH CENTURY GERMANY, AUSTRIA, AND FRANCE With preface by Ronald S. Lauder, foreword by Renée Price, and contributions by Alessandra Comini, Stuart Pyhrr, Elizabeth Szancer Kujawski, Ann Temkin, Eugene Thaw, Christian Witt-Dörring, and William D. Wixom PRESTEL MUNICH • LONDON • NEW YORK 001-023-NGRLC-FRONTMATTER 01.09.11 08:52 Seite 4 This catalogue has been published in conjunction with the exhibition The Ronald S. Lauder Collection: Selections from the 3rd Century BC to the 20th Century. Germany, Austria, and France Neue Galerie New York, October 27, 2011 – April 2, 2012 Director of publications: Scott Gutterman Managing editor: Janis Staggs Editorial assistance: Liesbet van Leemput Curator, Ronald S . Lauder Collection: Elizabeth Szancer K ujawski Exhibition designer: Peter de Kimpe Installation: Tom Zoufaly Book design: Richard Pandiscio, William Loccisano / Pandiscio Co. Translation: Steven Lindberg Project coordination: Anja Besserer Production: Andrea Cobré Origination: royalmedia, Munich Printing and Binding: APPL aprinta, W emding for the text © Neue Galerie, New Y ork, 2011 © Prestel Verlag, Munich · London · New Y ork 2011 Prestel, a member of V erlagsgruppe Random House GmbH Prestel Verlag Neumarkter Strasse 28 81673 Munich +49 (0)89 4136-0 Tel. -

Brice Marden Bibliography

G A G O S I A N Brice Marden Bibliography Selected Monographs and Solo Exhibition Catalogues: 2019 Brice Marden: Workbook. New York: Gagosian. 2018 Rales, Emily Wei, Ali Nemerov, and Suzanne Hudson. Brice Marden. Potomac and New York: Glenstone Museum and D.A.P. 2017 Hills, Paul, Noah Dillon, Gary Hume, Tim Marlow and Brice Marden. Brice Marden. London: Gagosian. 2016 Connors, Matt and Brice Marden. Brice Marden. New York: Matthew Marks Gallery. 2015 Brice Marden: Notebook Sept. 1964–Sept.1967. New York: Karma. Brice Marden: Notebook Feb. 1968–. New York: Karma. 2013 Brice Marden: Book of Images, 1970. New York: Karma. Costello, Eileen. Brice Marden. New York: Phaidon. Galvez, Paul. Brice Marden: Graphite Drawings. New York: Matthew Marks Gallery. Weiss, Jeffrey, et al. Brice Marden: Red Yellow Blue. New York: Gagosian Gallery. 2012 Anfam, David. Brice Marden: Ru Ware, Marbles, Polke. New York: Matthew Marks Gallery. Brown, Robert. Brice Marden. Zürich: Thomas Ammann Fine Art. 2010 Weiss, Jeffrey. Brice Marden: Letters. New York: Matthew Marks Gallery. 2008 Dannenberger, Hanne and Jörg Daur. Brice Marden – Jawlensky-Preisträger: Retrospektive der Druckgraphik. Wiesbaden: Museum Wiesbaden. Ehrenworth, Andrew, and Sonalea Shukri. Brice Marden: Prints. New York: Susan Sheehan Gallery. 2007 Müller, Christian. Brice Marden: Werke auf Papier. Basel: Kunstmuseum Basel. 2006 Garrels, Gary, Brenda Richardson, and Richard Shiff. Plane Image: A Brice Marden Retrospective. New York: Museum of Modern Art. Liebmann, Lisa. Brice Marden: Paintings on Marble. New York: Matthew Marks Gallery. 2003 Keller, Eva, and Regula Malin. Brice Marden. Zürich : Daros Services AG and Scalo. 2002 Duncan, Michael. Brice Marden at Gemini. -

Bleckner Biography

ROSS BLECKNER BIOGRAPHY Born in New York City, New York, 1949. Education: New York University, NYC, B.A., 1971. California Institute of the Arts, Valencia, California, M.F.A., 1973. Lives in New York City. Selected Solo Shows: 1983 Mary Boone Gallery, NYC, NY. 1986 Mario Diacono Gallery, Boston, Massachusetts. Mary Boone Gallery, NYC, NY. 1987 Mary Boone Gallery, NYC, NY. 1988 San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, California. Mary Boone Gallery, NYC, NY. 1989 Milwaukee Art Museum, Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Contemporary Arts Museum, Houston, Texas. Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. 1990 Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Canada. Kunsthalle Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland. 1991 Kolnischer Kunstverein, Koln, Germany. Moderna Museet, Stockholm, Sweden. Mary Boone Gallery, NYC, NY. 1993 Galerie Max Hetzler, Koln, Germany. 1994 Mary Boone Gallery, NYC, NY. 1995 Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, NYC, NY. Astrup Fearnley Museet for Moderne Kunst, Oslo, Norway. I.V.A.M., Centre Julio Gonzalez, Valencia, Spain. 1996 Mary Boone Gallery, NYC, NY. 1997 Galerie Daniel Templon, Paris, France. Bawag Foundation, Vienna, Austria. 1999 Mary Boone Gallery, NYC, NY. 2000 Mario Diacono Gallery, Boston, Massachusetts. Galerie Ernst Beyeler, Basel, Switzerland. Maureen Paley/Interim Art, London, England. ROSS BLECKNER BIOGRAPHY (continued) : Selected Solo Shows: 2001 Mary Boone Gallery, NYC, NY. 2003 Lehmann Maupin Gallery, NYC, NY. Mary Boone Gallery, NYC, NY. 2004 “Dialogue with Space”, Esbjerg Art Museum, Esbjerg, Denmark. 2005 Ruzicska Gallery, Salzburg, Austria. 2007 Thomas Ammann Fine Art, Zurich, Switzerland. Cais Gallery, Seoul, South Korea. Mary Boone Gallery, NYC, NY. 2008 “New Paintings”, Imago Galleries, Palm Desert, California. 2010 Mary Boone Gallery, NYC, NY. -

The Most Important Works of Art of the Twentieth Century

This PDF is a selection from a published volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: Conceptual Revolutions in Twentieth-Century Art Volume Author/Editor: David W. Galenson Volume Publisher: Cambridge University Press Volume ISBN: 978-0-521-11232-1 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/gale08-1 Publication Date: October 2009 Title: The Most Important Works of Art of the Twentieth Century Author: David W. Galenson URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c5786 Chapter 3: The Most Important Works of Art of the Twentieth Century Introduction Quality in art is not just a matter of private experience. There is a consensus of taste. Clement Greenberg1 Important works of art embody important innovations. The most important works of art are those that announce very important innovations. There is considerable interest in identifying the most important artists, and their most important works, not only among those who study art professionally, but also among a wider public. The distinguished art historian Meyer Schapiro recognized that this is due in large part to the market value of works of art: “The great interest in painting and sculpture (versus poetry) arises precisely from its unique character as art that produces expensive, rare, and speculative commodities.”2 Schapiro’s insight suggests one means of identifying the most important artists, through analysis of prices at public sales.3 This strategy is less useful in identifying the most important individual works of art, however, for these rarely, if ever, come to market. An alternative is to survey the judgments of art experts. One way to do this is by analyzing textbooks. -

Pop Art with Roy Lichtenstein

January 2020 The Studiowith ART HIST RY KIDS Pop Art with Roy Lichtenstein Observe | Discuss | Discover | Create | Connect Pop Art with The Studiowith Roy Lichtenstein ART HIST RY KIDS INTRODUCTION The art of the ordinary Roy Lichtenstein’s successful art career was based on one simple idea – creating fine art inspired by images we see everyday. His art captures the ordinary things that surround us – advertisements, comic books, the painting of other famous artists like Picasso, Mondrian, Matisse, and Monet, and even Micky Mouse cartoons. He took these ideas and recreated them on a larger than life scale. Most of his can- vases are grand and oversized – they are truly bold and impactful when seen in person! He also infused little bits of commentary in his art, and he became known for his skillful use of parody. You don’t need to study every piece of art that’s included in this guide. Feel free to choose just a few that are most interesting to your kids. A range of subject matter is included here, but if some of these paintings are too intense for your kids– just skip them for now, and come back to them when they are older! There’s no hurry, and there are plenty of paintings included here that are perfect for young kids. Pop Art looks out into the world. This is your week to look closely at the “ art and chat about it. We’ll learn all It doesn’t look like a painting of about Lichtenstein and his art next something, it looks like the thing week. -

S I G N a T U R E He Had So Many More Stories to Tell

SIGNATURE by Seth Thomas Pietras ’01 He Had So Many More Most of my exposure to Kirk occurred this past work hard, play hard, on the pitch and off, nihil in Stories to Tell spring at the A.W. Mellon Lecture Series at the moderato—a credo Kirk catapulted to a new level. efore I knew it, I had a large stack of National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. During Following the lectures and my visit with Kirk, I books on my lap—books about paradigm the series, I marveled that someone as distin- sat down with his former student Jeffrey Weiss, Bshifts and non-Euclidean geometry in guished as he would introduce himself week after chief curator of modern and contemporary art at modern art. “If you’re interested in what I’m week. Each time he arrived at the podium, it was: the National Gallery, to whom Kirk had referred saying, you need to read these,” Kirk said. “Then “Thank you for coming. I am Kirk Varnedoe.” me. Our discussion, originally intended to be an forget about it all and just look at the art.” During the fourth lecture, however, I realized informational session on modern art, rapidly I had encountered Kirk Varnedoe ’67 on the that even in a crowd of hundreds of informed resembled two kids discussing their favorite front cover of Rugby Magazine months earlier, patrons who had waited hours to gain admit- superhero; we were discussing Kirk. “He has and as a fellow rugger with a mind for art history, tance, recognition was not guaranteed. -

Dorothy Lichtenstein (Dl)

THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART ORAL HISTORY PROGRAM INTERVIEW WITH: DOROTHY LICHTENSTEIN (DL) NTERVIEWER: AGNES GUND (AG) LOCATION: NEW YORK, NEW YORK DATE: MAY 6, 1998 BEGIN MINICASSETTE MASTER TAPE 1, SIDE A AG: I'd like to thank you, first of all, for doing this. It's very nice of you. The first question that I'd like to ask you is, how did you and Roy meet, the first time? DL: The first time we met, I was working at a gallery, the Bianchini Gallery. That was around the corner from the Castelli Gallery at 4 East 77th Street. We were on 78th Street, and, in fact, that's the gallery that Rosa Esmond has now, Ubu Gallery [16 East 78th Street]. AG: Oh, is that her gallery? DL: Yes. We were doing a show called The Great American Supermarket, based on the fact that so much of the work in the early '60s imitated commercial products and ads, so we thought to set the exhibition up. AG: That's great. And this was a contemporary gallery? DL: Yes. When I started working there, Paul Bianchini owned it, and he did mostly drawing shows of modern masters, but, say, French and Europeans and mostly pre-war, but he would have had Dubuffet and Giacometti. AG: And he was a friend of Leo's [Castelli]. MoMA Archives Oral History: D. Lichtenstein page 1 of 29 DL: Well, he ran this gallery. He knew Leo, and of course it was very exciting. We thought Leo's gallery was the most exciting place. -

“Just What Was It That Made U.S. Art So Different, So Appealing?”

“JUST WHAT WAS IT THAT MADE U.S. ART SO DIFFERENT, SO APPEALING?”: CASE STUDIES OF THE CRITICAL RECEPTION OF AMERICAN AVANT-GARDE PAINTING IN LONDON, 1950-1964 by FRANK G. SPICER III Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation Adviser: Dr. Ellen G. Landau Department of Art History and Art CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY May, 2009 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of Frank G. Spicer III ______________________________________________________ Doctor of Philosophy candidate for the ________________________________degree *. Dr. Ellen G. Landau (signed)_______________________________________________ (chair of the committee) ________________________________________________Dr. Anne Helmreich Dr. Henry Adams ________________________________________________ Dr. Kurt Koenigsberger ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ December 18, 2008 (date) _______________________ *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. Table of Contents List of Figures 2 Acknowledgements 7 Abstract 12 Introduction 14 Chapter I. Historiography of Secondary Literature 23 II. The London Milieu 49 III. The Early Period: 1946/1950-55 73 IV. The Middle Period: 1956-59: Part 1, The Tate 94 V. The Middle Period: 1956-59: Part 2 127 VI. The Later Period: 1960-1962 171 VII. The Later Period: 1963-64: Part 1 213 VIII. The Later Period: 1963-64: Part 2 250 Concluding Remarks 286 Figures 299 Bibliography 384 1 List of Figures Fig. 1 Richard Hamilton Just What Is It That Makes Today’s Homes So Different, So Appealing? (1956) Fig. 2 Modern Art in the United States Catalogue Cover Fig. 3 The New American Painting Catalogue Cover Fig. -

Annual Report 2003 Annual Report 2003

THE CLEVELAND MUSEUM OF ART ANNUAL REPORT 2003 ANNUAL REPORT 2003 1 ARcover2003.p65 1 6/1/2004, 11:41 PM Annual Report 2003 ARpp01-21.p65 1 6/1/2004, 11:45 PM The Cleveland Cover: School The Annual Report The type is Bembo right in the United 46, 68, 72, 82, 87, 92, Museum of Art children are enthralled was produced by the and TheSans adapted States of America or 100; Becky Bristol: p. 11150 East with the ten litho- External Affairs for this publication. abroad and may not 95; Philip Brutz: pp. Boulevard graphs in Color division of the Composed with be reproduced in any 90 (right), 96; © Cleveland, Ohio Numeral Series (cour- Cleveland Museum of Adobe PC form or medium Disney/Pixar: p. 94; 44106-1797 tesy Margo Leavin Art. PageMaker 6.5. without permission Gregory M. Donley: Copyright © 2004 Gallery, Los Angeles), Narrative: Gregory Photography credits: from the copyright pp. 9 (left), 12, 13, on view in the holders. The follow- 37, 39, 44 (top), 45 The Cleveland M. Donley Works of art in the Museum of Art landmark exhibition ing photographers are (bottom), 47 (bot- Jasper Johns: Numbers. Editing: Barbara J. collection were pho- acknowledged: tom), 49 (top), 67, All rights reserved. Bradley and Kathleen tographed by museum Frontispiece: The Howard Agresti: pp. 71, 77, 79, 80, 89 No portion of this Mills photographers 1, 7, 8 (all), 10 (both), (all); Ann Koslow: p. publication may be museum and lagoon Howard Agriesti and in winter. Design: Thomas H. 36, 38, 40, 43, 44 71 (left); Shannon reproduced in any Barnard Gary Kirchenbauer; (middle and bottom), Masterson: p. -

Kirk Varnedoe Papers, 1890-2006 (Bulk 1970-2003)

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8dv1hvn Online items available Finding aid for the Kirk Varnedoe papers, 1890-2006 (bulk 1970-2003) Annette Leddy Finding aid for the Kirk Varnedoe 2008.M.60 1 papers, 1890-2006 (bulk 1970-2003) Descriptive Summary Title: Kirk Varnedoe papers Date (inclusive): 1890-2006 (bulk 1970-2003) Number: 2008.M.60 Creator/Collector: Varnedoe, Kirk, 1946-2003 Physical Description: 61.08 Linear Feet(138 boxes) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles 90049-1688 [email protected] URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/askref (310) 440-7390 Abstract: Papers of critic and curator Kirk Varnedoe include student papers and lecture notes, research files for exhibitions and publications, typescripts and audio tapes of lectures, and a small amount of material related to his position at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in English Biographical/Historical Note Kirk Varnedoe was born in Savannah, Georgia in 1946 to a wealthy and distinguished Southern family. He attended Williams College, where he began studying studio art, but soon switched to art history under the influence of Professor Lane Faison. He also played college football and, after graduating, returned to coach the football team and teach art history for a year. He then earned a Ph.D. at Stanford under Rodin scholar Albert Elsen, with whom he collaborated on an exhibition and catalog about the profusion of drawings falsely attributed to Rodin. -

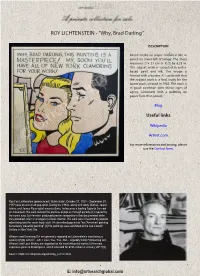

Lichtenstein Why Brad Darling

ROY LICHTENSTEIN - "Why, Brad Darling" DESCRIPTION Mixed media on paper. Initialled (RL) in pencil on lower-left of image. The sheet measures 21x 21 cm or 8.25 by 8.25 in. The subject work is executed in water- based paint and ink. The image is framed with a border. It is probable that the subject work is a final study for the iconic work, created in 1962. The work is in good condition with minor signs of aging, consistent with a painting on paper from that period. Blog Useful links Wikipedia Artnet.com For more information and pricing, please use the Contact form. Roy Fox Lichtenstein (pronounced /ˈlɪktənˌstaɪn/; October 27, 1923 – September 29, 1997) was an American pop artist. During the 1960s, along with Andy Warhol, Jasper Johns, and James Rosenquist among others, he became a leading figure in the new art movement. His work defined the premise of pop art through parody.[2] Inspired by the comic strip, Lichtenstein produced precise compositions that documented while they parodied, often in a tongue-in-cheek manner. His work was influenced by popular advertising and the comic book style. He described pop art as "not 'American' painting but actually industrial painting".[3] His paintings were exhibited at the Leo Castelli Gallery in New York City. Whaam! and Drowning Girl are generally regarded as Lichtenstein's most famous works,[4][5][6] with Oh, Jeff...I Love You, Too...But... arguably third.[7] Drowning Girl, Whaam! and Look Mickey are regarded as his most influential works.[8] His most expensive piece is Masterpiece, which was sold for $165 million in January 2017.[9] Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roy_Lichtenstein E: [email protected].