Proba the Prophet Mnemosyne Supplements Late Antique Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

SMATHERS LIBRARIES’ LATIN AND GREEK RARE BOOKS COLLECTION UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2016 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS page LECTORI: TO THE READER ........................................................................................ 20 LATIN AUTHORS.......................................................................................................... 24 Ammianus ............................................................................................................... 24 Title: Rerum gestarum quae extant, libri XIV-XXXI. What exists of the Histories, books 14-31. ................................................................................. 24 Apuleius .................................................................................................................. 24 Title: Opera. Works. ......................................................................................... 24 Title: L. Apuleii Madaurensis Opera omnia quae exstant. All works of L. Apuleius of Madaurus which are extant. ....................................................... 25 See also PA6207 .A2 1825a ............................................................................ 26 Augustine ................................................................................................................ 26 Title: De Civitate Dei Libri XXII. 22 Books about the City of God. ..................... 26 Title: Commentarii in Omnes Divi Pauli Epistolas. Commentary on All the Letters of Saint Paul. .................................................................................... -

An Introduction to Catholicism

This page intentionally left blank AN INTRODUCTION TO CATHOLICISM The Vatican. The Inquisition. Contraception. Celibacy. Apparitions and miracles. Plots and scandals. The Catholic Church is seldom out of the news. But what do its one billion adherents really believe, and how do they put their beliefs into practice in worship, in the family, and in society? This down-to-earth account goes back to the early Christian creeds to uncover the roots of modern Catholic thinking. It avoids getting bogged down in theological technicalities and throws light on aspects of the Church’s institutional structure and liturgical practice that even Catholics can find baffling: Why go to confession? How are people made saints? What is “infallible” about the pope? Topics addressed include: scripture and tradition; sacraments and prayer; popular piety; personal and social morality; reform, mission, and interreligious dialogue. Lawrence Cunningham, a theologian, prize-winning writer, and university teacher, provides an overview of Catholicism today which will be indispensable for undergraduates and lay study groups. lawrence s. cunningham is John A. O’Brien Professor of Theology at the University of Notre Dame. His scholarly interests are in the areas of systematic theology and culture, Christian spirituality, and the history of Christian spirituality. His most recent book is A Brief History of Saints. He has edited or written twenty other books and is co-editor of the academic monograph series “Studies in Theology and Spirituality.” He has won three awards for his teaching and has been honored four times by the Catholic Press Association for his writing. AN INTRODUCTION TO CATHOLICISM LAWRENCE S. -

Susan Boynton)

Child Oblates and Young Singers in the Medieval Liturgy (Susan Boynton) Child oblation: parents’ offering of a child as a donation to a monastery Terms commonly used for younger singers: infantes (children): up to about 7 years old pueri (boys) or puellae (girls): about 7-14 juvencule: girls of school age scolares: novices (girls) Guido of Arezzo (ca. 991-ca. 1033): Italian monk at the abbey of Pomposa in Northern Italy Notker Balbulus (ca. 840-912): a monk at the abbey of Saint Gall in Switzerland Notker’s Liber hymnorum- collection of sequences for Mass originating with Notker Ekkehard IV (ca. 980-after 1057): a teacher, poet, and chronicler at Saint Gall Aelfric Bata (fl. 1005): an Anglo-Saxon monk at Winchester, author of the Colloquies customary: compilation of prescriptions for life in a monastery, including the liturgy ordinal: outline of the liturgical ceremonial for the church year, especially feasts Cluny: Benedictine abbey in medieval Burgundy, directly subject to the Pope Liber tramitis: Cluniac customary from the abbey of Farfa (near Rome), ca. 1050 Ulrich of Zell: Cluniac monk who compiled customs of Cluny ca. 1070-80 Bernard: [in this context] Cluniac monk who compiled customs of Cluny ca. 1080 Lanfranc, Archbishop of Canterbury (1070-1089): wrote customary for Canterbury cathedral morrow mass: mass celebrated in the morning by members of a monastic community Saint Arnulf in Metz: Benedictine abbey Regularis concordia: Late tenth-century customary created for the English monastic reform Fleury: Benedictine monastery in the Loire valley armarius: monastic librarian who was also responsible for the organization of the liturgy. -

A Genettean Reading of Petronius' Satyrica

NIHIL SINE RATIONE FACIO: A GENETTEAN READING OF PETRONIUS’ SATYRICA BY OLIVER SCHWAZER Thesis submitted to University College London for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy DEPARTMENT OF GREEK AND LATIN UNIVERSITY COLLEGE LONDON 1 DECLARATION I, Oliver Schwazer, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Signed: _________________________________ 2 ABSTRACT My thesis is a narratological analysis of Petronius’ Satyrica, particularly of the first section taking place in South Italy (Petron. 1–99), based on the methodology and terminology of Gérard Genette. There are two main objectives for the present study, which are closely connected to each other. One the one hand, I wish to identify and analyse the narrative characteristics of the Satyrica, including a selection of its literary models and the ways in which they are imitated or transformed and embedded in a new narrative schema, as well as the impact, which those texts that are connected to it have on our interpretation of the work. My narratological investigation of transtextuality in the case of Petronius includes: the assessment of matters of onymity and pseudonymity, rhematic and thematic titles, and the real and implied author in the sections on para-, inter- and metatexts; features belonging to the categories of narrative voice, mood, and time in the section on the narration (‘narrating’) and the récit (‘narrative’); the hypertextual relationships between the Satyrica and a selection of its potential models or sources in the section on the histoire (‘story’); and the architext or genre of the Satyrica. -

Nomination Form International Memory of the World Register

Nomination form International Memory of the World Register 1.0 Checklist Nominees may find the following checklist useful before sending the nomination form to the International Memory of the World Secretariat. The information provided in italics on the form is there for guidance only and should be deleted once the sections have been completed. x Summary completed (section 1) x Nomination and contact details completed (section 2) x Declaration of Authority signed and dated (section 2) If this is a joint nomination, section 2 appropriately modified, and all Declarations of x Authority obtained x Documentary heritage identified (sections 3.1 – 3.3) x History/provenance completed (section 3.4) x Bibliography completed (section 3.5) Names, qualifications and contact details of up to three independent people or x organizations recorded (section 3.6) x Details of owner completed (section 4.1) x Details of custodian – if different from owner – completed (section 4.2) x Details of legal status completed (section 4.3) x Details of accessibility completed (section 4.4) x Details of copyright status completed (section 4.5) x Evidence presented to support fulfilment of the criteria? (section 5) x Additional information provided (section 6) x Details of consultation with stakeholders completed (section 7) x Assessment of risk completed (section 8) Summary of Preservation and Access Management Plan completed. If there is no x formal Plan attach details about current and/or planned access, storage and custody arrangements (section 9) x Any other information provided – if applicable (section 10) Suitable reproduction quality photographs identified to illustrate the documentary x heritage. -

18-27Outubro October

FESTIVAL DE ÓRGÃO DA MADEIRA 10TH MADEIRA ORGAN FESTIVAL 18-27 OUTUBRO OCTOBER MADEIRA E PORTO SANTO SEIS SÉCULOS DE MÚSICA PARA ÓRGÃO SIX CENTURIES OF ORGAN MUSIC 2 MADEIRA ORGAN FESTIVAL Festival de Órgão da Madeira 2019 Madeira Organ Festival 2019 O 10º Festival de Órgão da Madeira acon- The 10th Madeira Organ Festival takes tece num ano especial de celebrações da place in a special year of celebrations in the história do Arquipélago da Madeira e, por history of the Madeira Archipelago and, for esse motivo, apresenta-se com uma progra- this reason, presents a program dedicated to mação dedicada a “Seis Séculos de Música “Six Centuries of Organ Music”, inviting to a para Órgão” convidando a uma viagem musical journey through the centuries and musical através dos séculos e do patrimó- the organ heritage of the Region. nio organístico existente na Região. This Festival already conquered a prom- É um Festival ao qual já é reconhecido um inent place on the international cultural lugar de destaque no palco cultural inter- scene and affirmed itself as a reference in nacional, afirmando-se, também, como um the touristic and cultural environment of cartaz turístico e cultural de referência na Madeira, for the quality and uniqueness of Madeira pela qualidade e singularidade de its programming and great involvement with programação e grande envolvimento com the community, reinforcing its approach to a comunidade, reforçando a sua aproxima- the public and consequently affirming its ção ao público e consequente afirmação. position. Entre os dias -

Sanctus Sanctorum Exultatio Master's Thesis Presented

Variety within Unity: Sanctus sanctorum exultatio Master’s Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Peter Moeller Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University Thesis Committee Dr. Danielle Fosler-Lussier, Advisor Dr. Charles Atkinson Dr. Leslie Lockett ii Copyright by Peter Moeller 2018 iii Abstract When the Frankish King Pepin III declared, in the wake of the visit by Pope Stephen II and his retinue (752-57), that henceforth the churches in Francia would follow the Roman rite in the celebration of the liturgy, he began a process that would have far-reaching consequences for both the liturgy and its music. The chants of the Roman rite quickly came to be represented as divinely inspired—their melodies having been sung directly into the ear of Gregory the Great by the Holy Spirit in the form of a dove—and their textual and melodic ductus unalterable. Frankish singers, however, responded creatively to the imposition of the Roman liturgy and its music. While they could not alter the texts and melodies of the standard items of the mass and office, they could add newly composed texts and melodies to them. The result was the phenomenon often referred to as "troping," a term that covers a diverse array of practices ranging from adding melismas to the phrases of an Introit, adding texts to preexistent melismas, or composing completely new texts with music that could introduce and embellish almost any chant of the Mass or Office—the last-named being the "classic trope," as Bruno Stäblein called it. -

1 Tabakliteratur in Der Frühen Neuzeit

Die Poesie der Dinge Frühe Neuzeit Studien und Dokumente zur deutschen Literatur und Kultur im europäischen Kontext Herausgegeben von Achim Aurnhammer, Wilhelm Kühlmann, Jan-Dirk Müller, Martin Mulsow und Friedrich Vollhardt Band 237 Die Poesie der Dinge Ziele und Strategien der Wissensvermittlung im lateinischen Lehrgedicht der Frühen Neuzeit Herausgegeben von Ramunė Markevičiūtė und Bernd Roling Diese Publikation wurde ermöglicht durch die Förderung der Deutschen Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) und eine Ko-Finanzierung für Open-Access-Monografien und -Sammelbände der Freien Universität Berlin. ISBN 978-3-11-072068-6 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-072282-6 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-072296-3 ISSN 0934-5531 DOI https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110722826 Dieses Werk ist lizensiert unter einer Creative Commons Namensnennung 4.0 International Lizenz. Weitere Informationen finden Sie unter https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number: 2020951701 Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.dnb.de abrufbar. © 2021 Ramunė Markevičiūtė und Bernd Roling, publiziert von Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Dieses Buch ist als Open-Access-Publikation verfügbar über www.degruyter.com. Satz: Integra Software Services Pvt. Ltd. Druck und Bindung: CPI books GmbH, Leck www.degruyter.com Danksagung Die in diesem Band gesammelten Beiträge gehen aus der Tagung „Herausforde- rungen der Poetisierung von Wissenschaft“ hervor, die im Rahmen des Projekts der DFG-Forschungsgruppe 2305 Diskursivierungen von Neuem. Tradition und Novation in Texten und Bildern des Mittelalters und der Frühen Neuzeit vom 31. Januar bis zum 1. -

Greece's No. 1 Film Hit Comes to NYC Director Papakalaitis Tells TNH

S o C V st ΓΡΑΦΕΙ ΤΗΝ ΙΣΤΟΡΙΑ W ΤΟΥ ΕΛΛΗΝΙΣΜΟΥ E 101 ΑΠΟ ΤΟ 1915 The National Herald anniversa ry N www.thenationalherald.com A weeKlY greeK-AmericAn PublicAtion 1915-2016 VOL. 20, ISSUE 1004 January 7-13, 2017 c v $1.50 Greece’s No. 1 Film Hit Murdered Comes to NYC Director Greek Papakalaitis Tells TNH Ambassador By Penelope Karageorge you have a love story, you have in Brazil the to have an obstacle. So I decided Worlds Apart, the film that the obstacle would be reality, rocked Greece, breaking box of - the political/social crisis that’s Latest fice records and ranking No. 1 not only in Greece but all over over any film in the last decade, Europe.” is ready to win new audiences Is Worlds Apart a comedy or in the US. a tragedy? “It’s life,” he says. “I Team Sent from It opens Friday January 13 like to laugh. I like to cry. We Greece to investigate at Manhattan’s Village East Cin - have from the moment we are ema, a multiplex on Second Av - born until the end when we and receive a report enue. On January 20, the film leave this world all the colors of will open in Los Angeles at the life. So in this movie you laugh on the crime Arclight Cinema. With the odds a lot but you cry a lot. But don’t against a Greek film finding dis - say what happens!” He adds: ATHENS – A team of Greek po - tribution in the USA, it is excit - “The good thing about this film lice was sent to Rio de Janeiro ing to have Cinema Libre Studio is that that audiences all over to get a report on the murder of bring this exceptional film to the world understand the Greek Ambassador Kyriakos Americans. -

장크트 갈렌 수도원 도서관도 그 중 하나 : “책을 지니지 않는 수 도원은 무기를 갖추지 않는 요새와도 같다.” - 성 베네딕트의 수도 계율은 수도사들에게 《성서》 읽기를 엄히 명 하고 모든 수도사는 1년에 약 1만 5천 쪽(300쪽 책 50권)을 읽어 야 했다

두 바퀴로 세상여행 Cycling around the World . 여행은 고행(고통)이자 순례 . 순례는 고독의 실천 - 고독함 속에서 지혜로워지고 성숙하고 타인에 대한 소중함도 깨닫는다. - 홀로 있을 때 자연과 합일하고 내면을 향한 라이딩도 가능해진다. - 헬렌 켈러 : “나는 눈과 귀와 혀를 빼앗겼지만 영혼을 잃지 않았으므로 모든 것을 가진 것과 같다. 세상에서 가장 아름답고 소중한 것은 보이거나 만져지지 않는다. 단지 가슴으로만 느껴질 수 있다. 세상이 비록 고통으로 가득하더라도 그것을 극복하는 힘도 가득하다.” 세상의 벨로루트 : 자전거 실크로드 . 한국 - 제주도 : 1994년부터 자전거를 교통수단으로 이용하는 여 행 인프라와 소프트웨어 구축, 현재 658㎞의 자전거 도로 구축. 자동차 도로망 2694㎞의 24.4% - 해안 일주도로의 병행 자전거 도로 : 182㎞. 물이 잘 빠지 는 투스콘으로 포장. 제주 서귀포시 중심가와 관광지 등에 773곳, 1만4000대 용량의 자전거 보관소도 설치 - '안단테 쉐어링(Andante-Sharing) 서비스‘ : 누구나 필요 할 때 언제 어디서나 자전거를 빌려 탈 수 있는 자전거 올레 길 서비스. 제주도 전 지역을 13개 구간의 자전거 올레로 구분. 각 구간에 자유롭게 자전거를 반납·대여 가능한 파트 너 관계 구축. 각 구간은 자전거로 약 2시간 거리에 위치 . 네덜란드 - 전국 1만8000㎞ 자전거 도로, 모든 길이 이어져서 자전거를 이용한 통근·통학 및 도시간 여행도 활발 . 미국 - 남부 플로리다 주 키웨스트에서 북부 메인 주 칼레까지 4828㎞를 자전거도로로 잇는 동부해안 그린웨이 (ECG) 프로젝트 (1991년-2010년 완공) . 캐나다 - 1만8078㎞의 트랜스 캐나다 트레일을 1992년부터 구축 http://www.jnuri.net/news/articleView.html?idxno=13000 1. 유로벨로와 역사문화 . 14개 유로벨로 루트 : - 유럽의 자전거 실크로드 (1995년 이후) - European Cyclists’ Federation (ECF)가 각국의 자전거 도로를 연결해 유럽 대륙을 거대한 자전거 여행 천국으로 만드는 관광 프로젝트 - 규모 : 총 길이 7만여 ㎞에 14개 루트 - 기준 : 두 사람이 지나가기에 충분한 넓이, 30㎞마다 휴게소, 50㎞마다 숙박시설, 150㎞마다 기차와 버스 등 대중교통수단과 연결 등 http://www.eurovelo.org/ . -

Impact of Catholic Monastery Church Building on Cistercian Monastery Formation in Livonia and the State of the Teutonic Order During 13Th and 14Th Century

Scientific Journal of Latvia University of Life Sciences and Technologies Landscape Architecture and Art, Volume 12, Number 12 DOI: 10.22616/j.landarchart.2018.12.07 Impact of Catholic Monastery Church Building on Cistercian Monastery Formation in Livonia and the State of the Teutonic Order during 13th and 14th Century Silvija Ozola, Riga Technical University Abstract. Convinced Christians, in order to sacrifice themselves to God, became monks. In Italy and other remote places or at important traffic roads, building of monasteries for religious, educating and social needs was started, services and schools were organized, accommodation for travellers provided. Without applying concrete, a homogeneous planning monumental monastery churches with massive walls, restrained décor, wooden ceilings, semi cylindrical ridge or altarpiece (Latin: presbyterium) at the building eastern end were built. In churches, rooms with small windows were dark and enigmatic. Due to the impact of relics, the dead and martyrs’ commemoration cult and ideology, basilicas had more extended planning: at the nave’s eastern end a podium for the altar was made. In walls a semicircle planning chancel’s niche or apse and windows were built. In order to organize ritual processions, chapels for extra altars arranged in the cross-nave or transept. The entrance into the apse joined both side-naves and surrounded by the chancel. The building’s plan obtained a shape of a Latin cross. Symbolism was not the determinant factor, but rather the functionality of room. The transept, which earlier had been considered as underlying, became more important than the nave, which since the 5th century searches for fireproof cover formation and new planning and vault solutions were necessary. -

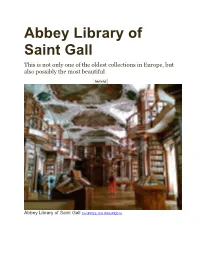

Abbey Library of Saint Gall This Is Not Only One of the Oldest Collections in Europe, but Also Possibly the Most Beautiful

Abbey Library of Saint Gall This is not only one of the oldest collections in Europe, but also possibly the most beautiful. Add to list Abbey Library of Saint Gall CHIPPEE ON WIKIPEDIA 4,720 There are beautiful old libraries and then there is the Abbey Library of Saint Gall, which may not only be one of the oldest surviving libraries in Europe but certainly one of the most beautiful. According to the Abbey of Saint Gall’s website (Abtei St. Gallen in German), the earliest evidence of a library collection on the site dates back to around 820 CE, in plans that show a library attached to the main church. The Abbey is said to have followed the Rule of St. Benedict, a portion of which prescribes the study of literature, should a library available, so it is no wonder that the abbey itself would have been built with one. As the abbey grew over the years, so did its library, and soon the site became known for its collection of illuminated manuscripts and writings, as well as a leading center for science and Western culture around the 10th century. In the mid-18th century, the world-renowned collection was moved to a new library space which was lavishly decorated in a Baroque rococo style. Elaborate artworks were installed in the ceiling which were framed by flowing, curved moldings, giving the space a timeless and fantastical aspect. The wooden balconies are shaped into flowering shapes and designs. Oh, and also the books the historic collection was also on display if you could look past the surroundings to pay attention to them.