Multiple Literary Cultures in Telugu Court, Temple, and Public

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Classical Persian Literature Bahman Solati (Ph.D), 2015 University of California, Berkeley [email protected]

Classical Persian Literature Bahman Solati (Ph.D), 2015 University of California, Berkeley [email protected] Introduction Studying the roots of a particular literary history enables us to better understand the allusions the literature transmits and why we appreciate them. It also allows us to foresee how the literature may progress.1 I will try to keep this attitude in the reader’s mind in offering this brief summary of medieval Persian literature, a formidable task considering the variety and wealth of the texts and documentation on the subject.2 In this study we will pay special attention to the development of the Persian literature over the last millennia, focusing in particular on the initial development and background of various literary genres in Persian. Although the concept of literary genres is rather subjective and unstable,3 reviewing them is nonetheless a useful approach for a synopsis, facilitating greater understanding, deeper argumentation, and further speculation than would a simple listing of dates, titles, and basic biographical facts of the giants of Persian literature. Also key to literary examination is diachronicity, or the outlining of literary development through successive generations and periods. Thriving Persian literature, undoubtedly shaped by historic events, lends itself to this approach: one can observe vast differences between the Persian literature of the tenth century and that of the eleventh or the twelfth, and so on.4 The fourteenth century stands as a bridge between the previous and the later periods, the Mongol and Timurid, followed by the Ṣafavids in Persia and the Mughals in India. Given the importance of local courts and their support of poets and writers, it is quite understandable that literature would be significantly influenced by schools of thought in different provinces of the Persian world.5 In this essay, I use the word literature to refer to the written word adeptly and artistically created. -

Language and Literature

1 Indian Languages and Literature Introduction Thousands of years ago, the people of the Harappan civilisation knew how to write. Unfortunately, their script has not yet been deciphered. Despite this setback, it is safe to state that the literary traditions of India go back to over 3,000 years ago. India is a huge land with a continuous history spanning several millennia. There is a staggering degree of variety and diversity in the languages and dialects spoken by Indians. This diversity is a result of the influx of languages and ideas from all over the continent, mostly through migration from Central, Eastern and Western Asia. There are differences and variations in the languages and dialects as a result of several factors – ethnicity, history, geography and others. There is a broad social integration among all the speakers of a certain language. In the beginning languages and dialects developed in the different regions of the country in relative isolation. In India, languages are often a mark of identity of a person and define regional boundaries. Cultural mixing among various races and communities led to the mixing of languages and dialects to a great extent, although they still maintain regional identity. In free India, the broad geographical distribution pattern of major language groups was used as one of the decisive factors for the formation of states. This gave a new political meaning to the geographical pattern of the linguistic distribution in the country. According to the 1961 census figures, the most comprehensive data on languages collected in India, there were 187 languages spoken by different sections of our society. -

Glossary of Literary Terms

Glossary of Critical Terms for Prose Adapted from “LitWeb,” The Norton Introduction to Literature Study Space http://www.wwnorton.com/college/english/litweb10/glossary/C.aspx Action Any event or series of events depicted in a literary work; an event may be verbal as well as physical, so that speaking or telling a story within the story may be an event. Allusion A brief, often implicit and indirect reference within a literary text to something outside the text, whether another text (e.g. the Bible, a myth, another literary work, a painting, or a piece of music) or any imaginary or historical person, place, or thing. Ambiguity When we are involved in interpretation—figuring out what different elements in a story “mean”—we are responding to a work’s ambiguity. This means that the work is open to several simultaneous interpretations. Language, especially when manipulated artistically, can communicate more than one meaning, encouraging our interpretations. Antagonist A character or a nonhuman force that opposes, or is in conflict with, the protagonist. Anticlimax An event or series of events usually at the end of a narrative that contrast with the tension building up before. Antihero A protagonist who is in one way or another the very opposite of a traditional hero. Instead of being courageous and determined, for instance, an antihero might be timid, hypersensitive, and indecisive to the point of paralysis. Antiheroes are especially common in modern literary works. Archetype A character, ritual, symbol, or plot pattern that recurs in the myth and literature of many cultures; examples include the scapegoat or trickster (character type), the rite of passage (ritual), and the quest or descent into the underworld (plot pattern). -

Telugu Newspapers and Periodicals in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana States: a Study

International Journal of Library and Information Studies Vol.8(4) Oct-Dec, 2018 ISSN: 2231-4911 Telugu Newspapers and Periodicals in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana States: A study Dastagiri Dudekula Library Assistant IIIT RK Valley Idupulapaya, Vempalli Andhra Pradesh 516330 K.V.N Rajeswara Rao Librarian SVR Engineering College Nandyal Kopparthi, Adisesu Library Assistant IIIT Nuzividu Abstract – The main objective of this study is to evaluate the Telugu newspapers and periodicals through Registrar of Newspapers for India database. The results unveil; the majority of the Newspapers/periodicals published in Andhra Pradesh when compared to Telangana state. Out of 5722 publications 2449 (42.80%) are ‘Monthly’ publications 1696(29.64%) are ‘Daily’ and 738(12.90%) are weekly publications. Geographically 527(15.98%) are published from Vishakhapatnam in Andhra Pradesh, and 1059(43.60%) are published from Hyderabad in Telangana state. The result of this study will help the research scholars and administrators of Telugu Newspapers and Periodical publications, as well as people who are interested in Telugu language. The study will also facilitate librarians and anybody interested to enhance usage of a Telugu literature by analyzing the RNI database. Keywords: The Office of the Registrar of Newspapers for India, RNI, Telugu Newspapers, Telugu Periodicals, Bibliometric studies. INTRODUCTION Print media, as you know is one of them. Print media is one of the oldest and basic forms of mass communication. It includes newspapers, weeklies, magazines, monthlies and other forms of printed journals. A basic understanding of the print media is essential in the study of mass communication. The contribution of print media in providing information and transfer of knowledge is remarkable. -

All the Nathas Or Nat Hayogis Are Worshippers of Siva and Followers

8ull. Ind. Inst. Hist. Med. Vol. XIII. pp. 4-15. INFLUENCE OF NATHAYOGIS ON TELUGU LITERATURE M. VENKATA REDDY· & B. RAMA RAo·· ABSTRACT Nathayogis were worshippers of Siva and played an impor- tant role in the history of medieval Indian mysticism. Nine nathas are famous, among whom Matsyendranatha and Gorakhnatha are known for their miracles and mystic powers. Tbere is a controversy about the names of nine nathas and other siddhas. Thirty great siddhas are listed in Hathaprad [pika and Hathara- tnaval ] The influence of natha cult in Andhra region is very great Several literary compositions appeared in Telugu against the background of nathism. Nannecodadeva,the author of'Kumar asarnbbavamu mentions sada ngayoga 'and also respects the nine nathas as adisiddhas. T\~o traditions of asanas after Vas istha and Matsyendra are mentioned Ly Kolani Ganapatideva in·sivayogasaramu. He also considers vajrfsana, mukrasana and guptasana as synonyms of siddhasa na. suka, Vamadeva, Matsyendr a and Janaka are mentioned as adepts in SivaY0ga. Navanathacaritra by Gaurana is a work in the popular metre dealing with the adventures of the nine nathas. Phan ibhaua in Paratattvarasayanamu explains yoga in great detail. Vedantaviir t ikarn of Pararnanandayati mentions the navanathas and their activities and also quotes the one and a quarter lakh varieties of laya. Vaidyasaramu or Nava- natha Siddha Pr ad Ipika by Erlapap Perayya is said to have been written on the lines of the Siddhikriyas written by Navanatha siddh as. INTRODUCTlON : All the nathas or nat ha yogis are worshippers of siva and followers of sai visrn which is one of the oldest religious cults of India. -

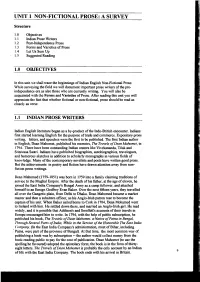

Unit 1 Non-Fictional Prose: a Survey

UNIT 1 NON-FICTIONAL PROSE: A SURVEY Structure I .O Objectives 1.1 Indian Prose Writers 1.2 Post-Independence Prose 1.3 Forms and Varieties of Prose 1.4 Let Us Sum Up 1.5 Suggested Reading 1.0 OBJECTIVES In this unit we shall trace the beginnings of Indian English Non-Fictional Prose. While surveying the field we will document important prose writers of the pre- independence era as also those who are currently writing. You will also be acquainted with the Forms and Varieties of Prose. After reading this unit you will appreciate the fact that whether fictional or non-fictional, prose should be read as closely as verse. 1.1 INDIAN PROSE WRITERS lndian English literature began as a by-product of the Indo-British encounter. Indians first started learning English for the purpose of trade and commerce. Expository+prose writing, letters, and speeches were the first to be published. The first Indian author in English, Dean Mahomet, published his memoirs, The Travels ofDean Mahomet, in 1794. There have been outstanding Indian orators like Vivekananda, Tilak and Srinivasa Sastri. Indians have published biographies, autobiographies, travelogues, and humorous sketches in addition to scholarly monographs in various fields of knowledge. Many of the contemporary novelists and poets have written good prose. But the achievements in poetry and fiction have drawn armtion away from non- fiction prose writings. Dean Mahomed ( 1759- 185 1) was born in 1759 into a fhmily claiming traditions of service to the Mughal Empire. After the death of his fbther, at the age of eleven, he .ioined the East India Company's Bengal Army as a camp follower, and attached h~mselfto an Ensign Godfrey Evan Baker. -

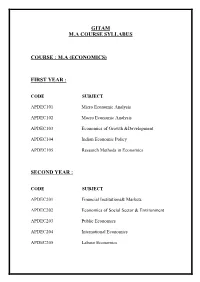

Gitam Ma Course Syllabus Course : Ma (Economics) First Year

GITAM M.A COURSE SYLLABUS COURSE : M.A (ECONOMICS) FIRST YEAR : CODE SUBJECT APDEC101 Micro Economic Analysis APDEC102 Macro Economic Analysis APDEC103 Economics of Growth &Development APDEC104 Indian Economic Policy APDEC105 Research Methods in Economics SECOND YEAR : CODE SUBJECT APDEC201 Financial Institutions& Markets APDEC202 Economics of Social Sector & Environment APDEC203 Public Economics APDEC204 International Economics APDEC205 Labour Economics COURSE : M.A (ENGLISH) FIRST YEAR : CODE SUBJECT APDEN101 British Poetry APDEN102 British Drama APDEN103 British Novel APDEN104 Aspects of Language APDEN105 Literary Criticism and Theory SECOND YEAR : CODE SUBJECT APDEN201 American Literature APDEN202 Indian English Literature APDEN203 New Literatures in English APDEN204 Australian Literature APDEN205 American Novel ANU COURSE: MASTER OF ARTS:ENGLISH MA(ENGLISH)- SUBJECT LIST: FIRST YEAR: CODE SUBJEST DEG01 HISTORY OF THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE DEG02 SHAKESPEARE DEG03 MODERN LITERATURE-I(1550-1700) DEG04 MODERN LITERATURE-II(1700-1850) DEG05 MODERN ENGLICH LITERATURE-III(1850-1950) FINAL YEAR: DEGO21 LITERARY CRITICISM DEGO22 AMERICAN LITERATURE DEGO23 INDIAN ENGLISH LITERATURE DEGO24 TWENTIETH CENTURY POETRY AND DRAMA DEGO25 TWENTIETH CENTURY PROSE AND FICTION COURSE: MASTER OF ARTS:TELUGU MA(TELUGU)- SUBJECTLIST: FIRST YEAR: CODE SUBJECT DT01 PRESCRIBED TEXT DT02 INTRODUCTION TO GENERAL LINGUISTICS DT03 OUTLINES OF TELUGU LITERATURE DT04 STUDY OF TELUGU GRAMMAR, PROSODY & POETICS DT05 MODERN TRENDS IN TELUGU POETRY FINAL YEAR: DT21 LITERARY CRITICISM &THEORY OF LITERATURE DT22 DRAVIDIAN PHILOGY & EVOLUTION OF TELUGU LANGUAGE DT23 SPECIAL STUDY : SREENADHA DT24 WOMEN STUDIES IN TELUGU LITERATURE COURSE: MASTER OF ARTS: ECONOMICS MA(ECONOMICS)- SUBJECTLIST FIRST YEAR: CODE SUBJECT DEC01 MICRO ECONOMICS DEC02 MACRO ECONOMICS DEC03 GOVERNMENT FINANCE DEC04 EVOLUTION OF ECONOMICS DOCTRIN DEC05 QUANTITATIVE METHODS FINAL YEAR: IN ADDITION TO THE FOLLOWING FOUR COMPULSORY PAPERS, THE CANDIDATE HAS TO SELECT ONE OF THE FOLLOWING ELECTIVE GROUPS. -

The Tradition of Kuchipudi Dance-Dramas1

The Tradition of Kuchipudi Dance-dramas1 Sunil Kothari The Historical Background Of the many branches of learning which flourished in Andhra from very early ti.mes not the least noteworthy is the tradition of the Natyashastra, embracing the tw1n arts of music and dance. The Natyashastra mentions the Andhra region m connection with a particular style of dance in the context of the Vritti-s. Bharata refers to Kaishiki Vrittt: a delicate and graceful movement in the dance of this reg1on .2 A particular raga by the name of Andhri was the contribution of this region to the music of India. The dance traditions in Andhra can be traced to various sources. The ancient temples, the Buddhist ruins excavated at Nagarjunakonda, Amaravati, Ghantasala, Jagayyapet and Bhattiprole indicate a flourishing dance tradition in Andhra. Of these the Amaravati stupa relics are the most ancient dating back to the second century B.C.3 They reveal the great choreographic possibilities of group and composite dances called pind1bandha-s, mentioned by Bharata and on which Abhinavagupta gives a detailed commentary in Abhinava Bharat1: 4 The history of dance, divided into two periods for the sake of convenience on account of the continuity of the Sanskrit and the later development of the vernacular regional languages, admits of two broad limits : from the second century B.C. to the ninth century A.D. and from the tenth century A.D. to the eighteenth century A.D. The latter period coincides with the growth of various regional styles and with the development of the tradition of Kuchipudi dance dramas. -

A History of English Literature MICHAEL ALEXANDER

A History of English Literature MICHAEL ALEXANDER [p. iv] © Michael Alexander 2000 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W 1 P 0LP. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The author has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2000 by MACMILLAN PRESS LTD Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS and London Companies and representatives throughout the world ISBN 0-333-91397-3 hardcover ISBN 0-333-67226-7 paperback A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 09 08 07 06 05 04 03 02 O1 00 Typeset by Footnote Graphics, Warminster, Wilts Printed in Great Britain by Antony Rowe Ltd, Chippenham, Wilts [p. v] Contents Acknowledgements The harvest of literacy Preface Further reading Abbreviations 2 Middle English Literature: 1066-1500 Introduction The new writing Literary history Handwriting -

Why Should Anyone Be Familiar with Persian Literature?

Annals of Language and Literature Volume 4, Issue 1, 2020, PP 11-18 ISSN 2637-5869 Why should anyone be Familiar with Persian Literature? Shabnam Khoshnood1, Dr. Ali reza Salehi2*, Dr. Ali reza Ghooche zadeh2 1M.A student, Persian language and literature department, Electronic branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran 2Persian language and literature department, Electronic branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran *Corresponding Author: Dr. Ali reza Salehi, Persian language and literature department, Electronic branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran, Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Literature is a tool for conveying concepts, thoughts, emotions and feelings to others that has always played an important and undeniable role in human life. Literature encompasses all aspects of human life as in love and affection, friendship and loyalty, self-sacrifice, justice and cruelty, manhood and humanity, are concepts that have been emphasized in various forms in the literature of different nations of the world. Poets and writers have endeavored to be heretics in the form of words and sentences and to promote these concepts and ideas to their community. Literature is still one of the most important identifiers of nations and ethnicities that no other factor has been able to capture. As a rich treasure trove of informative and educational material, Persian literature has played an important role in the development and reinforcement of social ideas and values in society, which this mission continues to do best. In this article, we attempt to explain the status of Persian literature and its importance. Keywords: language, literature, human, life, religion, culture. INTRODUCTION possible to educate without using the humanities elite. -

Roman Prose and Satire. If We Keep to Schedule, We Will Finish with Augustine's Confessions, Selections Actually. So Our Concl

Roman prose and satire. If we keep to schedule, we will finish with Augustine’s Confessions, selections actually. So our conclusion will bring us from the ancient world to the rise of the West, from the epic journey to the inward struggle to master the self, from the lyrics of Sappho to the lamentations of the fallen. We will work quickly, but thoroughly and systematically. We will define and refine key terms and ideas. We will develop themes and questions. We will work toward some comprehensive thoughts about our literature and the cultures that come with it. Lots of reading, but when it is this good, who doesn’t ask for more? Now the basics: two papers, a midterm and a final, some shorter activities, and lots of dialogue in class. The final will be comprehensive. CATEGORY 1 EH 381, Victorian Literature and Culture (Cat. 1) Ullrich, TTH 12:30-1:50 The Victorians have a terrible problem with PR. Often simplified as repressive, Victorian England was a time of impressive cultural change. The Victorian era was the first era to call into question institutional Christianity on a large scale. Many distinctively “modern” innovations and cultural concepts made significant strides during this time period, including democracy, feminism, unionization of workers, socialism, Marxism. This is the age of Darwin, Marx, and early Freud, as well as Queen Victorian, the Oxford Movement, and Utilitarianism. This course is designed as a survey of the major Victorian writers and the cultural events which transformed the era. The course covers the time period from 1832-1900. -

Unit 31 Indian Languages and Literature

UNIT 31 INDIAN LANGUAGES AND LITERATURE Structure 31.0 Objectives 31.1 Introduction 31.2 Arabic and Persian 31.3 Sanskrit 31.4 North India 31.4.1 Hindi 31.4.2 Urdu 31.4.3 Punjabi 3 1.5 Western India 31.5.1 %uj& 315.2 Marathi 31.6 Eastern India 31.6.1 Bengali 31.6.2 Asaunek 31.6.3 Ckiya 3 1.7 South Indian Languages 31.7.1 Td 31.7.2 Teluy 31.7.3 Kamada 31.7.4 Malayalam 31.8 Let Us Sum Up 31.9 Key Words 31.10 Answers to Cbeck Your Progress Exercises In this unit, we will discuss the languages and literatme tbat flourished m India during the 16th to mid 18th centuries. Aftea gomg through this unit you will: ,. be able to appreciate the variety and richness of literam produced during the period under study; know about the main literary works in India in the following languages: Arabic, Persian, Urdu, Sanskrit, HiLdi, Punjabi, Bengali, Assamese, Oriya, Tamil, Telugu, Malayalam and Kannada; and .a be familiar wit. some of the main historians, writers and poets writing in the above languages. ' cr 31.1 INTRODUCTION The Mughal rule created some semblance of political unity m India. Further, it not only encouraged an integtated internal matket and an increase m foreign trade, but also generated an atmosphere of creative intellectual activity. Apart from the Empexors, the Mughal princes and nobles, too, patronised literary activity. Tbe regional com.of the Rajput Rajas and the ' Deccan and South Indian rulers also did not lag bebind.