Japanese Laws Related to Airport Development and the Need to Revise Them Isaku Shibata

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PROFILE of KYUSHU 2021 New Perspectives

Measure development of Kyushu Industrial Strategy for Kyushu-Okinawa Regional Growth―Kyushu-Okinawa Earth Strategy II The Kyushu-Okinawa Regional Council for Industrial Competitiveness promotes initiatives in four strategic areas that leverage Kyushu and Okinawa’s strengths to achieve the sustainable development of Kyushu, a gateway to Asia trying its best to work on solving new issues. The Council developed this strategy in 2014 under a public-private partnership. As of 2021, 21 projects are underway on Stage 2,incorporating PROFILE OF KYUSHU 2021 new perspectives. Strategic Areas 21 projects promoted under the Kyushu-Okinawa Earth Strategy II Project on Realizing Kyushu Hydrogen Energy Society Project on Promoting Industrial Base Formation for Clean Medical, Healthcare, Geothermal and Hot Spring Heat Energy Energy & and Cosmetics Project on Establishing Base Formation for Marine Environment Health Renewable Energy Industry Clean Project on Promoting Asia’s Advanced Base Formation for Northern Kyushu Automotive Industry Earth Project on Establishing Base for Organic Photonics and Electronics Industry Agriculture, Forestry, Sightseeing Project on Promoting Industrial Base Formation for Fisheries, and Food Kyushu and Asia Environmental Energy Industry Agriculture Tourism Project on Promoting Healthcare Industry Medical, Healthcare, Project on Creating Innovative Medical Products and Cosmetics Project on Promoting Biotechnology Industry Project on Promoting Karatsu Cosmetics Initiative Four strategic areas Four Russia Cross-cutting Initiatives -

Face Express, a New Facial Recognition Technology for Boarding Procedures at NRT and HND Is Coming Soon ! It’S Seamless and Contactless Experience !

NEWS RELEASE 25 March 2021 Face Express, a new facial recognition technology for boarding procedures at NRT and HND is coming soon ! It’s seamless and contactless experience ! The operating companies of Narita International Airport (Narita International Airport Corporation - NAA) and Tokyo International Airport (Tokyo International Air Terminal Corporation - TIAT), will commence their trial for "Face Express”, a new boarding procedure using facial recognition technology, in April 2021. Once passengers register their facial image in Face Express, they will be able to access and proceed through subsequent procedures at the airport (check-in, baggage drop, security checkpoint entrance, boarding gate, etc.) without showing their passport and boarding pass. Its introduction will expedite seamless boarding procedures and, because most processing is touchless, it will also reduce the infection risks posed by person-to- person contact. The two airports will each commence their trial operation as below and prepare for a full launch in July. Start of trial operation : Tuesday, 13 April 2021 Participating airlines: All Nippon Airways, Japan Airlines (more airlines will participate later) Locations : [South Wing Terminal 1] Check-in Island C / Gates 51 to 57A [ Terminal 2 ]Check-in Island K / Gates 61 to 66, 71, 81 to 83, 91 to 93 • Service details are available at the following URL: https://www.narita-airport.jp/en/faceexpress/ Start of trial operation : Tuesday, 13 April 2021 Participating airlines: Airlines operating international flights at HND Locations: [Terminal 3] Check-in Islands D, E, G, H, I, J / All gates [Terminal 2*] Check-in Islands P, Q, T / All gates *All international counters are closed at present. -

Kyushu China Taipei

Sapporo 北京 Japan Seoul South Korea Hiroshima Busan Oita Tokyo Nagoya Fukuoka Osaka Saga Nagasaki Kumamoto Kagoshima Miyazaki Shanghai Kyushu China Taipei Hong Kong Macao Hanoi Taiwan Thailand Vietnam Philippines Bangkok Manila Ho chi minh Malaysia Kuala Lumpur Singapore Singapore Shimonoseki Mojiko Moji Kokura Hakata Takeo Saga Tosu Haiki Onsen Shin Tosu Hita Yufuin Beppu Sasebo Kurume Oita Chikugo Funagoya Chugoku Expressway Huis Ten Bosch Arita Shin Omuta Miyaji Saiki Shin Tamana Aso Kumamoto Higo Ozu Nagasaki Nobeoka Shin Shimonoseki Misumi Yatsushiro Shin Yatsushiro Hitoyoshi Shin Minamata Izumi Yoshimatsu Shimonoseki IC Miyazaki Kirishima Onsen Minami Miyazaki Sendai Kirishima Jingu Aoshima Mojiko IC Hayato Kitago Kagoshima Obi Moji Port Kagoshima Chuo Nichinan Kyushu Expressway Nango Makurazaki Ibusuki Kokura Kitakyushu (Kokura) Shinmonji Port Fukuoka Kokura Higashi IC Kitakyushu Airport Kitakyushu Suou Nada Sea Airport Hakata Port International Terminal Fukuoka IC Hakata Port Hakata Nakatsu Fukuoka Airport Fukuoka Airport Buzen IC Hakata Yobuko Tenjin Usa Beppu Expressway Nakatsu IC Dazaifu IC Oita Airport Nishi Karatsu Oita Airport Kosoku Kiyama Karatsu Saga Tosu JCT Oita Hiji IC Oita AirportRoad Karatsu IC Tosu IC Hirado Imafuku IC Matsuura Shin Tosu Hita IC Oita Expressway Yamashirokubara IC Taniguchi IC Nagasaki Expressway Kurume IC Gulf of Beppu Saga Yamato IC Hita Beppu IC Kurume Hita Yufuin Imari Kurume Saga Yufuin IC Beppu Saza IC Imari Oita Saga Beppu Takeo Onsen Yufuin Oita Sasebo Chikugo Funagoya Amagase Oita IC Nishi-Kyushu -

Solar Frontier and Chopro Agree 29 MW Megasolar Project with Nagasaki Government to Build and Operate Prefecture’S Largest Megasolar Power Plant at Nagasaki Airport

NEWS RELEASE Solar Frontier and Chopro Agree 29 MW Megasolar Project with Nagasaki Government To build and operate Prefecture’s largest megasolar power plant at Nagasaki Airport Tokyo-April 1st 2014 -Solar Frontier and Chopro announced today that they have signed a letter of agreement with the Nagasaki Prefectural Government and the Land Development Public Corporation of Nagasaki Prefecture for a 29 MW megasolar power plant on land adjoining Nagasaki Airport, Japan. The agreement, regarding the construction and operation of the solar power plant, was signed on March 31, 2014. The upcoming megasolar project will be the largest in Nagasaki Prefecture and one of the largest in Japan. “Our Nagasaki project integrates the economical advantages of Solar Frontier’s CIS solar energy system solutions, from supplying high-performance CIS modules through to Operation & Maintenance, with Chopro’s expertise as an energy supplier local to Nagasaki,” said Hiroto Tamai, President and Representative Director of Solar Frontier. “Together with leading regional companies like Chopro, we will continue to meet the high demand for solar projects that offer competitive and reliable returns on investment.” After the Kansai International Airport Megasolar Power Plant, this will be the second large-scale installation at an airport that leverages Solar Frontier’s CIS thin-film technology. Compared to crystalline silicon modules, Solar Frontier’s CIS modules have a higher electricity yield (kWh/kWp) in real operating conditions, while their anti-glare properties ensure they don’t affect aircraft operations. “Our joint project is built on a history of trust with Solar Frontier. We now look forward to working on one of the world’s largest installations at an airport – at home in Nagasaki – and to contributing to the region’s economic growth and renewable energy initiative,” said Kenji Araki, Representative Director of Chopro. -

Rail Pass Guide Book(English)

JR KYUSHU RAIL PASS Sanyo-San’in-Northern Kyushu Pass JR KYUSHU TRAINS Details of trains Saga 佐賀県 Fukuoka 福岡県 u Rail Pass Holder B u Rail Pass Holder B Types and Prices Type and Price 7-day Pass: (Purchasing within Japan : ¥25,000) yush enef yush enef ¥23,000 Town of History and Hot Springs! JR K its Hokkaido Town of Gourmet cuisine and JR K its *Children between 6-11 will be charged half price. Where is "KYUSHU"? All Kyushu Area Northern Kyushu Area Southern Kyushu Area FUTABA shopping! JR Hakata City Validity Price Validity Price Validity Price International tourists who, in accordance with Japanese law, are deemed to be visiting on a Temporary Visitor 36+3 (Sanjyu-Roku plus San) Purchasing Prerequisite visa may purchase the pass. 3-day Pass ¥ 16,000 3-day Pass ¥ 9,500 3-day Pass ¥ 8,000 5-day Pass Accessible Areas The latest sightseeing train that started up in 2020! ¥ 18,500 JAPAN 5-day Pass *Children between 6-11 will be charged half price. This train takes you to 7 prefectures in Kyushu along ute Map Shimonoseki 7-day Pass ¥ 11,000 *Children under the age of 5 are free. However, when using a reserved seat, Ro ¥ 20,000 children under five will require a Children's JR Kyushu Rail Pass or ticket. 5 different routes for each day of the week. hu Wakamatsu us Mojiko y Kyoto Tokyo Hiroshima * All seats are Green Car seats (advance reservation required) K With many benefits at each International tourists who, in accordance with Japanese law, are deemed to be visiting on a Temporary Visitor R Kyushu Purchasing Prerequisite * You can board with the JR Kyushu Rail Pass Gift of tabi socks for customers J ⑩ Kokura Osaka shops of JR Hakata city visa may purchase the pass. -

One-Way Rental Car Makes Exploring Kyushu Easy! ~The Second Collaboration of Peach × Nippon Rent-A-Car Is a Kyushu-Only Campaign! ~

Press Release October 29, 2019 Peach Aviation Limited One-Way Rental Car Makes Exploring Kyushu Easy! ~The second collaboration of Peach × Nippon Rent-A-Car is a Kyushu-only campaign! ~ ・ This is campaign avaible only in Kyushu Nippon Rent-A-Car for a limited time. ・ Bargain campaign for customers flying on Peach’s Fukuoka, Nagasaki, Miyazaki, and Kagoshima routes ・ Using a rental car affords customers the opportunity to visit various sightseeing spots and sites in Kyushu Osaka October 29, 2019 - Peach Aviation Limited (“Peach”; Representative Director and CEO: Shinichi Inoue) and Nippon Rent-A-Car Service, Inc. (“Nippon Rent-A-Car”, President: Yoshimitsu Arahata) launch the Peach × Nippon Rent-A-Car collaboration “Exploring Kyushu with a rent-a-car short trip!” to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the foundation of Nippon Rent-A-Car. This campaign represents the second collaboration between Peach × Nippon Rent-A-Car following the Explore with a rent-a-car! Freedom Hokkaido campaign held from June 1 to September 30, 2019. For customers flying Peach`s Kyushu routes, (between Osaka (Kansai) to Fukuoka, Nagasaki, Miyazaki, and Kagoshima / between Tokyo (Narita) to Fukuoka, and between Sapporo (New Chitose) and Fukuoka (six routes in total)) bargain car rental is available between Fukuoka, Nagasaki, Miyazaki, and Kagoshima. Traveling around Kyushu in a rented car not only enriches customers’ trips but also opens opportunities to visit all manner of tourist locations and facilities. In this way, we want to contribute to the revitalization of Kyushu and to stimulate the local economy. This limited time campaign will run through the end of next March. -

Chapter 3 Aircraft Accident and Serious Incident Investigations

Chapter 3 Aircraft accident and serious incident investigations Chapter 3 Aircraft accident and serious incident investigations 1 Aircraft accidents and serious incidents to be investigated <Aircraft accidents to be investigated> ◎Paragraph 1, Article 2 of the Act for Establishment of the Japan Transport Safety Board (Definition of aircraft accident) The term "Aircraft Accident" as used in this Act shall mean the accident listed in each of the items in paragraph 1 of Article 76 of the Civil Aeronautics Act. ◎Paragraph 1, Article 76 of the Civil Aeronautics Act (Obligation to report) 1 Crash, collision or fire of aircraft; 2 Injury or death of any person, or destruction of any object caused by aircraft; 3 Death (except those specified in Ordinances of the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism) or disappearance of any person on board the aircraft; 4 Contact with other aircraft; and 5 Other accidents relating to aircraft specified in Ordinances of the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism. ◎Article 165-3 of the Ordinance for Enforcement of the Civil Aeronautics Act (Accidents related to aircraft prescribed in the Ordinances of the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism under item 5 of the paragraph1 of the Article 76 of the Act) The cases (excluding cases where the repair of a subject aircraft does not correspond to the major repair work) where navigating aircraft is damaged (except the sole damage of engine, cowling, engine accessory, propeller, wing tip, antenna, tire, brake or fairing). <Aircraft serious incidents to be investigated> ◎Item 2, Paragraph 2, Article 2 of the Act for Establishment of the Japan Transport Safety Board (Definition of aircraft serious incident) A situation where a pilot in command of an aircraft during flight recognized a risk of collision or contact with any other aircraft, or any other situations prescribed by the Ordinances of Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism under Article 76-2 of the Civil Aeronautics Act. -

Development of 10000 Series Rolling Stock for Tokyo Monorail

Hitachi Review Vol. 63 (2014), No. 10 641 Featured Articles Development of 10000 Series Rolling Stock for Tokyo Monorail Takuma Yamaguchi OVERVIEW: The 10000 Series rolling stock for the Tokyo Monorail is a Toru Nishino replacement for the 2000 Series that has been in use for the last 17 years. Naoji Ueki By adopting the latest technologies and a design in harmony with the surrounding area, the development has succeeded in building rolling stock Syuji Hirano that features: (1) expanded services (four-language multilingual information service utilizing the cars’ LCD displays, provision for oversize luggage, and barrier-free accessibility), (2) car design enhancements (exterior that harmonizes with surrounding area, Japanese-themed interior), (3) better environmental performance (use of LEDs for headlights and interior lighting, use of unpainted rolling stock), and (4) greater safety (installation of rolling stock information and control systems for driving control, indicator lights for doors that are opening and closing, barrier-free format for side display units, longer battery operation). INTRODUCTION From Monorail Hamamatsucho Station to Tennozu Isle Station, the monorail runs past central-city offices TOKYO Monorail celebrates its 50th anniversary this and residential buildings and offers views of Rainbow year, having commenced operation on September 17, Bridge and Odaiba. From Tennozu Isle Station and 1964 on the eve of the Tokyo Olympics. With the Ryutsu Center Station, it runs parallel to the Shutoko second Tokyo Olympics to take place in 2020 and Metropolitan Expressway, offering views of the Keihin an increasing number of international flights using Canal and nearby parkland as it passes by them at high Haneda Airport (Tokyo International Airport), Hitachi speed. -

Study on Airport Ownership and Management and the Ground Handling Market in Selected Non-European Union (EU) Countries

Study on airport DG MOVE, European ownership and Commission management and the ground handling market in selected non-EU countries Final Report Our ref: 22907301 June 2016 Client ref: MOVE/E1/SER/2015- 247-3 Study on airport DG MOVE, European ownership and Commission management and the ground handling market in selected non-EU countries Final Report Our ref: 22907301 June 2016 Client ref: MOVE/E1/SER/2015- 247-3 Prepared by: Prepared for: Steer Davies Gleave DG MOVE, European Commission 28-32 Upper Ground DM 28 - 0/110 London SE1 9PD Avenue de Bourget, 1 B-1049 Brussels (Evere) Belgium +44 20 7910 5000 www.steerdaviesgleave.com Steer Davies Gleave has prepared this material for DG MOVE, European Commission. This material may only be used within the context and scope for which Steer Davies Gleave has prepared it and may not be relied upon in part or whole by any third party or be used for any other purpose. Any person choosing to use any part of this material without the express and written permission of Steer Davies Gleave shall be deemed to confirm their agreement to indemnify Steer Davies Gleave for all loss or damage resulting therefrom. Steer Davies Gleave has prepared this material using professional practices and procedures using information available to it at the time and as such any new information could alter the validity of the results and conclusions made. The information and views set out in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the European Commission. -

Recommended Flight Routes to the Conference Venue

Recommended Flight Routes to the Conference Venue Seoul, Shanghai Two flights / week Paris, London, Frankfurt, L.A., San Francisco, Seoul, ICRERA 2012 Nagasaki Bangkok, Beijing, Nagasaki Conference Venue Hong Kong, Kuala Tokyo Airport Lumpur, Hong Kong, Int’l Singapore, etc. Narita Airport Int’l (Haneda) Most of Int’l Cities 1hour Airport 2 hours 65‐85 min Seoul, Busan, Shanghai, Beijing, 10 min Taipei, Bangkok, Takaramachi Stop JR Takaramachi Stop Hanoi, Manila, Fukuoka Nagasaki Dalian, Singapore, Airport Hong Kong, Ho Chi 140 min Station Minh, Jeju, etc. 5min (1) Flying directly to Nagasaki Airport Direct but infrequent flights to Nagasaki Airport are available only from Seoul (Incheon) and Shanghai (Pudong), but not everyday. Please make sure the flight schedule if you can find convenient ones. (2) Connecting at Tokyo International Airport (Haneda) If you are thinking of taking a connecting flight to Nagasaki, flying via Tokyo International Airport (Haneda) is most recommended. You can directly fly to Haneda Airport from more than 10 major cities around the world, and can easily connect to frequent domestic flights to Nagasaki Airport. Flight time between Haneda and Nagasaki is approximately two hours. (3) Connecting at Narita International Airport The other international airport in the Tokyo area is Narita International Airport (formerly also known as New Tokyo International Airport). While Narita International Airport handles more international air traffic than Haneda Airport, any connecting flights to Nagasaki Airport are NOT available. Thus, you need to take a limousine bus to Haneda Airport for connection. The buses depart every 20 minutes and the ride takes 65 to 85 minutes. -

PASMO PASSPORT to Be Released This Fall!

July 11, 2019 PASMO Committee ~3 Popular Sanrio Characters All on 1 Card!~ IC Card Ticket with Special Benefits Exclusively for Foreign Visitors PASMO PASSPORT to Be Released This Fall! The transportation IC Card issuer Pasmo Co., Ltd. are launching PASMO PASSPORT, an IC Card ticket for foreign visitors to Japan, to be sold at select stations from fall 2019. This PASMO PASSPORT is an IC Card whose name carried the meaning of it being a second passport for traveling Japan. It has an original design for PASMO PASSPORT that gathers Hello Kitty, Cinnamoroll, and Pompompurin, three characters from Sanrio Co., Ltd. popular with foreign guests from Asia and elsewhere, in front of a background of famous Japanese tourist attractions and cherry blossoms. It’s a cute (IC) Card that can be brought back home as a souvenir from Japan. Just like regular PASMO, it can be used for traveling on trains and buses that accept IC Cards as well as for shopping with e-money, and it can be used repeatedly by top up it. You can also receive special benefits in stores by presenting the front of this Card. (Front design) ©1976, 1996, 2001, 2019 SANRIO CO., LTD. APPROVAL NO. G601061 * PASMO is a registered trademark of PASMO, Co., Ltd. [PASMO PASSPORT Overview] 1. Name PASMO PASSPORT 2. Release date (planned) September 1, 2019 3. Contents Can be used on trains and buses that accept IC Cards in the Kanto area and other locations across Japan, as well as to shop with e-money 4. Sold to Foreign travelers visiting to Japan 5. -

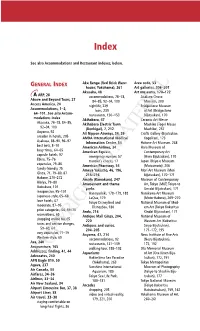

Copyrighted Material

18_543229 bindex.qxd 5/18/04 10:06 AM Page 295 Index See also Accommodations and Restaurant indexes, below. GENERAL INDEX Aka Renga (Red Brick Ware- Area code, 53 house; Yokohama), 261 Art galleries, 206–207 Akasaka, 48 Art museums, 170–172 A ARP, 28 accommodations, 76–78, Asakura Choso Above and Beyond Tours, 27 84–85, 92–94, 100 Museum, 200 Access America, 24 nightlife, 229 Bridgestone Museum Accommodations, 1–2, bars, 239 of Art (Bridgestone 64–101. See also Accom- restaurants, 150–153 Bijutsukan), 170 modations Index Akihabara, 47 Ceramic Art Messe Akasaka, 76–78, 84–85, Akihabara Electric Town Mashiko (Togei Messe 92–94, 100 (Denkigai), 7, 212 Mashiko), 257 Aoyama, 92 All Nippon Airways, 34, 39 Crafts Gallery (Bijutsukan arcades in hotels, 205 AMDA International Medical Kogeikan), 173 Asakusa, 88–90, 96–97 Information Center, 54 Hakone Art Museum, 268 best bets, 8–10 American Airlines, 34 Hara Museum of busy times, 64–65 American Express Contemporary Art capsule hotels, 97 emergency number, 57 (Hara Bijutsukan), 170 Ebisu, 75–76 traveler’s checks, 17 Japan Ukiyo-e Museum expensive, 79–86 American Pharmacy, 54 (Matsumoto), 206 family-friendly, 75 Ameya Yokocho, 46, 196, Mori Art Museum (Mori Ginza, 71, 79–80, 87 215–216 Bijutsukan), 170–171 Hakone, 270–272 Amida (Kamakura), 247 Museum of Contemporary Hibiya, 79–80 Amusement and theme Art, Tokyo (MOT; Tokyo-to Ikebukuro, 101 parks Gendai Bijutsukan), 171 inexpensive, 95–101 Hanayashiki, 178–179, 188 Narukawa Art Museum Japanese-style, 65–68 LaQua, 179 (Moto-Hakone), 269–270 love hotels,