Adb-Brief-140-Making-Water-Available

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Rivers of Mongolia

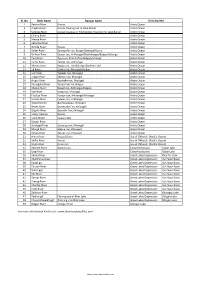

Sl. No River Name Russian Name Draining Into 1 Yenisei River Russia Arctic Ocean 2 Angara River Russia, flowing out of Lake Baikal Arctic Ocean 3 Selenge River Сэлэнгэ мөрөн in Sükhbaatar, flowing into Lake Baikal Arctic Ocean 4 Chikoy River Arctic Ocean 5 Menza River Arctic Ocean 6 Katantsa River Arctic Ocean 7 Dzhida River Russia Arctic Ocean 8 Zelter River Зэлтэрийн гол, Bulgan/Selenge/Russia Arctic Ocean 9 Orkhon River Орхон гол, Arkhangai/Övörkhangai/Bulgan/Selenge Arctic Ocean 10 Tuul River Туул гол, Khentii/Töv/Bulgan/Selenge Arctic Ocean 11 Tamir River Тамир гол, Arkhangai Arctic Ocean 12 Kharaa River Хараа гол, Töv/Selenge/Darkhan-Uul Arctic Ocean 13 Eg River Эгийн гол, Khövsgöl/Bulgan Arctic Ocean 14 Üür River Үүрийн гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 15 Uilgan River Уйлган гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 16 Arigiin River Аригийн гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 17 Tarvagatai River Тарвагтай гол, Bulgan Arctic Ocean 18 Khanui River Хануй гол, Arkhangai/Bulgan Arctic Ocean 19 Ider River Идэр гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 20 Chuluut River Чулуут гол, Arkhangai/Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 21 Suman River Суман гол, Arkhangai Arctic Ocean 22 Delgermörön Дэлгэрмөрөн, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 23 Beltes River Бэлтэсийн Гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 24 Bügsiin River Бүгсийн Гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 25 Lesser Yenisei Russia Arctic Ocean 26 Kyzyl-Khem Кызыл-Хем Arctic Ocean 27 Büsein River Arctic Ocean 28 Shishged River Шишгэд гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 29 Sharga River Шарга гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 30 Tengis River Тэнгис гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 31 Amur River Russia/China -

Journal Biology 2004 3

Mongolian Journal of Biological Sciences 2004 Vol. 2(1): 39-42 Hydrochemical Characteristics of Selenge River and its Tributaries on the Territory of Mongolia Bazarova J.G. 1, Dorzhieva S.G.1, Bazarov B.G. 1, Barkhutova D.D.2, Dagurova O.P.2, Namsaraev B.B. 2 and Zhargalova S.O.2 1Baikal Institute of Nature Management of SB RAS, Ulan-Ude, 2Institute of General and Experimental Biology of SB RAS, Ulan-Ude, E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Hydrochemical research of the Selenge and its main tributary the Orkhon river on the territory of Mongolia has been conducted. Concentrations of the main water ions were measured. Distribution of - + heavy metals was determined. Dynamics of biogenic elements (NO3 , NH4 , phosphates) and degree of phenol pollution was determined. Key words: Baikal, biogenic, heavy metals, ions, phenol, Selenge River Introduction river is polluted along its entire length. To assess the current ecological condition in the Mongolian During the last 30-40 years Lake Baikal has part of the Selenge river basin, it is necessary to been influenced by various anthropogenic factors. implement hydrobiological and hydrochemical Industrial and household waste water have changed monitoring. It requires information not only of the chemical composition of Baikal with a chemical composition, but of biogenic components deterioration in water quality in the basin territory. in the processes of accumulation and According to sustainable development policy, transformation in water, bottom sediments and river protection of Baikal region is considered -

Archaeological Investigations of Xiongnu Sites in the Tamir River

Archaeological Investigations of Xiongnu Sites in the Tamir River Valley Results of the 2005 Joint American-Mongolian Expedition to Tamiryn Ulaan Khoshuu, Ogii nuur, Arkhangai aimag, Mongolia David E. Purcell and Kimberly C. Spurr Flagstaff, Arizona (USA) During the summer of 2005 an archaeological investigations, and What is known points to this area archaeological expedition jointly their results, are the focus of this as one of the most important mounted by the Silkroad Foun- article, which is a preliminary and cultural regions in the world, a fact dation of Saratoga, California, incomplete record of the project recently recognized by the U.S.A. and the Mongolian National findings. Not all of the project data UNESCO through designation of University, Ulaanbataar, investi- — including osteological analysis of the Orkhon Valley as a World gated two sites near the the burials, descriptions or maps Heritage Site in 2004 (UNESCO confluence of the Tamir River with of the graves, or analyses of the 2006). Archaeological remains the Orkhon River in the Arkhangai artifacts — is available as of this indicate the region has been aimag of central Mongolia (Fig. 1). writing. Consequently, the greater occupied since the Paleolithic (circa The expedition was permitted emphasis falls on one of the two 750,000 years before present), (Registration Number 8, issued sites. It is hoped that through the with Neolithic sites found in great June 23, 2005) by the Ministry of Silkroad Foundation, the many numbers. As early as the Neolithic Education, Culture and Science of different collections from this period a pattern developed in Mongolia. The project had multiple project can be reunited in a which groups moved southward goals: archaeological investiga- scholarly publication. -

Tuul River Mongolia

HEALTHY RIVERS FOR ALL Tuul River Basin Report Card • 1 TUUL RIVER MONGOLIA BASIN HEALTH 2019 REPORT CARD Tuul River Basin Report Card • 2 TUUL RIVER BASIN: OVERVIEW The Tuul River headwaters begin in the Lower As of 2018, 1.45 million people were living within Khentii mountains of the Khan Khentii mountain the Tuul River basin, representing 46% of Mongolia’s range (48030’58.9” N, 108014’08.3” E). The river population, and more than 60% of the country’s flows southwest through the capital of Mongolia, GDP. Due to high levels of human migration into Ulaanbaatar, after which it eventually joins the the basin, land use change within the floodplains, Orkhon River in Orkhontuul soum where the Tuul lack of wastewater treatment within settled areas, River Basin ends (48056’55.1” N, 104047’53.2” E). The and gold mining in Zaamar soum of Tuv aimag and Orkhon River then joins the Selenge River to feed Burenkhangai soum of Bulgan aimag, the Tuul River Lake Baikal in the Russian Federation. The catchment has emerged as the most polluted river in Mongolia. area is approximately 50,000 km2, and the river itself These stressors, combined with a growing water is about 720 km long. Ulaanbaatar is approximately demand and changes in precipitation due to global 470 km upstream from where the Tuul River meets warming, have led to a scarcity of water and an the Orkhon River. interruption of river flow during the spring. The Tuul River basin includes a variety of landscapes Although much research has been conducted on the including mountain taiga and forest steppe in water quality and quantity of the Tuul River, there is the upper catchment, and predominantly steppe no uniform or consistent assessment on the state downstream of Ulaanbaatar City. -

Thesis Local Understanding of Hydro-Climate Changes

THESIS LOCAL UNDERSTANDING OF HYDRO-CLIMATE CHANGES IN MONGOLIA Submitted by Tumenjargal Sukh Department of Ecosystem Science and Sustainability In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the Degree of Master of Science Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado Fall 2012 Master’s Committee: Advisor: Steven Fassnacht Melinda Laituri Maria Fernandez-Gimenez Greg Butters Copyright by Tumenjargal Sukh 2012 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT LOCAL UNDERSTANDING OF HYDRO-CLIMATE CHANGES IN MONGOLIA Air temperatures have increased more in semi-arid regions than in many other parts of the world. Mongolia has an arid/semi-arid climate where much of the population is dependent upon the limited water resources, especially herders. This paper combines herder observations of changes in water availability in streams and from groundwater with an analysis of climatic and hydrologic change from station data to illustrate the degree of change of Mongolian water resources. We find that herders’ local knowledge of hydro-climatic changes is similar to the station based analysis. However, station data are spatially limited, so local knowledge can provide finer scale information on climate and hydrology. We focus on two regions in central Mongolia: the Jinst soum in Bayankhongor aimag in the desert steppe region and the Ikh-Tamir soum in Arkhangai aimag in the mountain steppe. As the temperatures have increased significantly (more in Ikh-Tamir than Jinst), precipitation amounts have decreased in Ikh-Tamir which corresponds to a decrease in streamflow, in particular, the average annual streamflow and the annual peak discharge. At Erdenemandal (Ikh-Tamir) the number of days with precipitation has decreased while at Horiult (Jinst) it has increased. -

Defining Territories and Empires: from Mongol Ulus to Russian Siberia1200-1800 Stephen Kotkin

Defining Territories and Empires: from Mongol Ulus to Russian Siberia1200-1800 Stephen Kotkin (Princeton University) Copyright (c) 1996 by the Slavic Research Center All rights reserved. The Russian empire's eventual displacement of the thirteenth-century Mongol ulus in Eurasia seems self-evident. The overthrow of the foreign yoke, defeat of various khanates, and conquest of Siberia constitute core aspects of the narratives on the formation of Russia's identity and political institutions. To those who disavow the Mongol influence, the Byzantine tradition serves as a counterweight. But the geopolitical turnabout is not a matter of dispute. Where Chingis Khan and his many descendants once held sway, the Riurikids (succeeded by the Romanovs) moved in. *1 Rather than the shortlived but ramified Mongol hegemony, which was mostly limited to the middle and southern parts of Eurasia, longterm overviews of the lands that became known as Siberia, or of its various subregions, typically begin with a chapter on "pre-history," which extends from the paleolithic to the moment of Russian arrival in the late sixteenth, early seventeenth centuries. *2 The goal is usually to enable the reader to understand what "human material" the Russians found and what "progress" was then achieved. Inherent in the narratives -- however sympathetic they may or may not be to the native peoples -- are assumptions about the historical advance deriving from the Russian arrival and socio-economic transformation. In short, the narratives are involved in legitimating Russia's conquest without any notion of alternatives. Of course, history can also be used to show that what seems natural did not exist forever but came into being; to reveal that there were other modes of existence, which were either pushed aside or folded into what then came to seem irreversible. -

Tuul River Basin Basin

GOVERNMENT OF MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT MONGOLIA I II III AND GREEN DEVELOPMENT Physical, Tuul river Socio-Economic geographical basin water Development and natural resource and and Future condition of water quality trend of the Tuul river Tuul River basin Basin IV V VI Water Water use Negative TUUL RIVER BASIN supply, water balance of the impacts on consumption- Tuul river basin basin water INTEGRATED WATER MANAGEMENT PLAN use and water resources demand, hydro- constructions VII VIII IX Main challenges River basin The organization and strategic integrated and control of objectives of the water resources the activities to river basin water management implement the Tuul management plan plan measures River Basin IWM INTEGRATED WATER MANAGEMENT PLAN plan Address: TUUL RIVER BASIN “Strengthening Integrated Water Resources Management in Mongolia” project Chingunjav Street, Bayangol District Ulaanbaatar-16050, Mongolia Tel/Fax: 362592, 363716 Website: http://iwrm.water.mn E-mail: [email protected] Ulaanbaatar 2012 Annex 1 of the Minister’s order ¹ A-102 of Environment and Green Development, dated on 03 December, 2012 TUUL RIVER BASIN INTEGRATED WATER MANAGEMENT PLAN (Phase 1, 2013-2015; Phase 2, 2016-2021) Ulaanbaatar 2012 DDC 555.7’015 Tu-90 This plan was developed within the framework of the “Strengthening Integrated Water Resources Management in Mongolia” project, funded by the Government of the Kingdom of the Netherlands at Ministry of Environment and Green Development of Mongolia Project Project Project Consulting Team National Director -

MONGOLIA Environmental Monitor 2003 40872

MONGOLIA Environmental Monitor 2003 40872 THE WORLD BANK 1818 H Street, NW Washington, D. C. 20433 U.S.A. Public Disclosure AuthorizedPublic Disclosure Authorized Tel: 202-477-1234 Fax: 202-477-6391 Telex: MCI 64145 WORLDBANK MCI 248423 WORLDBANK Internet: http://worldbank.org THE WORLD BANK MONGOLIA OFFICE Ulaanbaatar, 11 A Peace Avenue Ulaanbaatar 210648, Mongolia Public Disclosure AuthorizedPublic Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure AuthorizedPublic Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure AuthorizedPublic Disclosure Authorized THE WORLD BANK ENVIRONMENT MONITOR 2003 Land Resources and Their Management THE WORLD BANK CONTENTS PREFACE IV ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS V SECTION I: PHYSICAL FEATURES OF LAND 2 SECTION II: LAND, POVERTY, AND LIVELIHOODS 16 SECTION III: LEGAL AND INSTITUTIONAL DIMENSIONS OF LAND MANAGEMENT 24 SECTION IV: FUTURE CHALLENGES 32 MONGOLIA AT A GLANCE 33 NOTES 34 The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / THE WORLD BANK 1818 H Street, NW Washington, DC 20433 The World Bank Mongolia Office Ulaanbaatar, 11 A Peace Avenue Ulaanbaatar 210648, Mongolia All rights reserved. First printing June 2003 This document was prepared by a World Bank Team comprising Messrs./Mmes. Anna Corsi (ESDVP), Giovanna Dore (Task Team Leader), Tanvi Nagpal, and Tony Whitten (EASES); Robin Mearns (EASRD); Yarissa Richmond Lyngdoh (EASUR); H. Ykhanbai (Mongolia Ministry of Nature and Environment). Jeffrey Lecksell was responsible for the map design. Photos were taken by Giovanna Dore and Tony Whitten. Cover and layout design were done by Jim Cantrell. Inputs and comments by Messrs./Mmes. John Bruce (LEGEN), Jochen Becker, Gerhard Ruhrmann (Rheinbraun Engineering und Wasser - GmbH), Nicholas Crisp, John Dick, Michael Mullen (Food and Agriculture Organization), Clyde Goulden (Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia), Hans Hoffman (GTZ), Glenn Morgan, Sulistiovati Nainggolan (EASES), and Vera Songwe (EASPR) are gratefully acknowledged. -

River Water Quality of the Selenga-Baikal Basin: Part II—Metal Partitioning Under Different Hydroclimatic Conditions

water Article River Water Quality of the Selenga-Baikal Basin: Part II—Metal Partitioning under Different Hydroclimatic Conditions Nikolay Kasimov 1, Galina Shinkareva 1,* , Mikhail Lychagin 1, Sergey Chalov 1 , Margarita Pashkina 1, Josefin Thorslund 2 and Jerker Jarsjö 2 1 Faculty of Geography, Lomonosov Moscow State University, 119991 Moscow, Russia; [email protected] (N.K.); [email protected] (M.L.); [email protected] (S.C.); [email protected] (M.P.) 2 Department of Physical Geography and the Bolin Centre for Climate Research, Stockholm University, SE-106 91 Stockholm, Sweden; josefi[email protected] (J.T.); [email protected] (J.J.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +7-909-633-2239 Received: 4 July 2020; Accepted: 20 August 2020; Published: 26 August 2020 Abstract: The partitioning of metals and metalloids between their dissolved and suspended forms in river systems largely governs their mobility and bioavailability. However, most of the existing knowledge about catchment-scale metal partitioning in river systems is based on a limited number of observation points, which is not sufficient to characterize the complexity of large river systems. Here we present an extensive field-based dataset, composed of multi-year data from over 100 monitoring locations distributed over the large, transboundary Selenga River basin (of Russia and Mongolia), sampled during different hydrological seasons. The aim is to investigate on the basin scale, the influence of different hydroclimatic conditions on metal partitioning and transport. Our results showed that the investigated metals exhibited a wide range of different behaviors. Some metals were mostly found in the dissolved form (84–96% of Mo, U, B, and Sb on an average), whereas many others predominantly existed in suspension (66–87% of Al, Fe, Mn, Pb, Co, and Bi). -

Mongoliai Envirk7 NMENT Monitor 2004

E I R lAA E N T Monitor 2004 Public Disclosure Authorized 30053 _~~~~~~~~~~ -- Public Disclosure Authorized _~~ ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~r 41~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~- _.!@:_-7-~ - _ _., - -- ~~~~~~~~~~ ..I. Public Disclosure Authorized Environmental Cha-llenges of Urban D-evlopment -- - ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Public Disclosure Authorized t ~~~~THEWORLD BAN K Mongoliai ENVIRk7 NMENT Monitor 2004 Environmental Challenges of Urban Development THE WORLD BANK M 1'REFACE iii tIBBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS iV 'ECTION l: OVERVIEW OF THE URBAN TRANSFORMATION IN MONGOLIA 2 !ECTION 11: PRESSURES OF URBANIZATION 10 'ECTION III:TOWARD ENVIRONMENTALLY SUSTAINABLE URBAN AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT 24 ECTION IV: FUTURE CHALLENGES 30 MONGOLIA AT A GLANCE 31 NOTES 32 'I he International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / THE WORLD BANK 18'18 H Street, NW Washington, DC 20433 I he World Bank Mongolia Office 11 A Peace Avenue I laanbaatar 210648, Mongolia All rights reserved. First printing June 2004 'Ihis document was prepared by a World Bank team comprising Messrs./Mmes. Anna Corsi (ESDVP), Giovanna Dore, Tanvi Nagpal, and lony Whitten (EASES); Raja Iyer (EASUR) and the team of the Second Ulaanbaatar Urban Service Improvement Project; Salvador Rivera (i.ASEG) and the team of the Mongolia Improved Urban Stoves Project; Jim Cantrell designed the cover and layout of this document, and lIffrey Lecksell was responsible for the map design. [Liput and comments from Messrs./Mmes. Zafar Ahmad and Christopher Finch (EACIF); Tseveen Badam (Office of the Mayor, City of L laanbaatar); Rachel Kaufmann (SASES); Dr. Shiene Enkhtsetseg (Mongolia Ministry of Health); H. Ykhanbai, and Naavaan-Yunden (Oundar (Mongolia Ministry of Nature and Environment); Jitendra Shah (EASES); Dr. -

India & Mongolia in the Middle Ages – More Than Just a Connection

Ancient History of Asian Countries India & Mongolia in the Middle Ages – More Than Just a Connection By Mohan Gopal Author Mohan Gopal The Taj Mahal area and traced his lineage to a line of Turkic-Mongol warlords who alternately plagued, plundered, ruled and governed in greater or If there is one monument which conjures up an image of India, it lesser components a vast region which roughly spans the areas of is the Taj Mahal. It was constructed c. 1631 at the behest of Emperor present-day Turkey, southern Russia, the northern Middle East, Shah Jahan as the ultimate memorial and place of eternal rest for his central Asia, northern Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan and northern India. beloved wife, Mumtaj. The Taj, as it is commonly referred to, is for The most commonly known name in this lineage was Tamerlane, romanticists across the globe, the ultimate architectural poem of love born in 1336 in central Asia, also known as Timur the Lame, Timur etched in white marble with floral motifs inlaid with precious stones; the Great or Timur the Horrible, depending on which perspective one a monument of perfect geometrical balance and symmetry. In this took – that of his huge territorial conquests or the countless and mausoleum lie the tombs of Emperor Shah Jahan and his beloved endless massacres and lootings which formed the basis of them. queen. Babur chose the former perspective and with pride considered It may come as a surprise to many that this widely admired, loved himself a Timurid, a descendant of the mighty Timur. and romanticized world artefact which has come to be known as a Babur’s mother was Qutlugh Nigar Khanum. -

Sustainable Water Management in the Selenga-Baikal Basin

Sustainable Water Management in the Selenga-Baikal Basin Integrated Environmental Assessment for a Transboundary Watershed with Multiple Stressors Contact Integrated Water Resources Management – Model Region Mongolia – If you have any questions or suggestions, please do not hesitate to contact us: Dr. Daniel Karthe | [email protected] Philipp Theuring | [email protected] Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research, Magdeburg, Germany Acad. Prof. Dr. Nikolay Kasimov | [email protected] Dr. Sergey Chalov | [email protected] Lomonosov Moscow State University, Russia For further information and contacts, please refer to www.iwrm-momo.de Project Profi le Sustainable Water Management in the Selenga-Baikal Basin Integrated Environmental Assessment for a Transboundary Watershed with Multiple Stressors August 2014 Publisher: Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research (UFZ) Moscow Lomonosov State University Editors: Dr. Daniel Karthe | Dr. Sergey Chalov Layout: perner&schmidt werbung und design gmbh Sponsors: International Bureau of the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) Russian Geographical Society Links: www.ufz.de www.eng.geogr.msu.ru SELENGA-BAIKAL PROJECT Lake Baikal Page 2 SELENGA-BAIKAL PROJECT Table of Contents/Partners Table of Contents Page 1 Introduction . 4 2 Hydrochemical Monitoring in the Selenga-Baikal Basin . 5 3 Planning IWRM in the Kharaa River Model Region . 6 4 A Monitoring Concept for the Selenga-Baikal Basin . 7 5 Selected Publications . 8 Contact . 9 Partners Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research Lomonosov Moscow State University Associated partners are the Mongolian Academy of Sciences (Institutes of Geograpy and Geoecology), the Russian Academy of Sciences (Institute of Water Problems, the Joint Russian-Mongolian Complex Biological Expedition) and the Center for Environmental Systems Research of Kassel University, Germany.