The Geographies of Maori-Mormonism and the Creation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Secret Mormon Meetings of 1922

University of Nevada, Reno THE SECRET MORMON MEETINGS OF 1922 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History By Shannon Caldwell Montez C. Elizabeth Raymond, Ph.D. / Thesis Advisor December 2019 Copyright by Shannon Caldwell Montez 2019 All Rights Reserved UNIVERSITY OF NEVADA RENO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by SHANNON CALDWELL MONTEZ entitled The Secret Mormon Meetings of 1922 be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS C. Elizabeth Raymond, Ph.D., Advisor Cameron B. Strang, Ph.D., Committee Member Greta E. de Jong, Ph.D., Committee Member Erin E. Stiles, Ph.D., Graduate School Representative David W. Zeh, Ph.D., Dean, Graduate School December 2019 i Abstract B. H. Roberts presented information to the leadership of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in January of 1922 that fundamentally challenged the entire premise of their religious beliefs. New research shows that in addition to church leadership, this information was also presented during the neXt few months to a select group of highly educated Mormon men and women outside of church hierarchy. This group represented many aspects of Mormon belief, different areas of eXpertise, and varying approaches to dealing with challenging information. Their stories create a beautiful tapestry of Mormon life in the transition years from polygamy, frontier life, and resistance to statehood, assimilation, and respectability. A study of the people involved illuminates an important, overlooked, underappreciated, and eXciting period of Mormon history. -

Stories from General Conference PRIESTHOOD POWER, VOL. 2

Episode 27 Stories from General Conference PRIESTHOOD POWER, VOL. 2 NARRATOR: This is Stories from General Conference, volume two, on the topic of Priesthood Power. You are listening to the Mormon Channel. Worthy young men in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints have the privilege of receiving the Aaronic Priesthood. This allows them to belong to a quorum where they learn to serve and administer in some of the ordinances of the Church. In the April 1997 General Priesthood Meeting, Elder David B. Haight reminisced about his youth and how the priesthood helped him progress. (Elder David B. Haight, Priesthood Session, April 1997) “Those of you who are young today--and I'm thinking of the deacons who are assembled in meetings throughout the world--I remember when I was ordained a deacon by Bishop Adams. He took the place of my father when he died. My father baptized me, but he wasn't there when I received the Aaronic Priesthood. I remember the thrill that I had when I became a deacon and now held the priesthood, as they explained to me in a simple way and simple language that I had received the power to help in the organization and the moving forward of the Lord's program upon the earth. We receive that as 12-year-old boys. We go through those early ranks of the lesser priesthood--a deacon, a teacher, and then a priest--learning little by little, here a little and there a little, growing in knowledge and wisdom. That little testimony that you start out with begins to grow, and you see it magnifying and you see it building in a way that is understandable to you. -

December 14, 2018 To: General Authorities; General Auxiliary Presidencies; Area Seventies; Stake, Mission, District, and Temple

THE CHURCH OF JESUS GHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS OFFICE OF THE FIRST PRESIDENCY 47 EAST SOUTH TEMPLE STREET, SALT LAKE 0ITY, UTAH 84150-1200 December 14, 2018 To: General Authorities; General Auxiliary Presidencies; Area Seventies; Stake, Mission, District, andTemple Presidents; Bishops and Branch Presidents; Stake, District, Ward,and Branch Councils (To be read in sacrament meeting) Dear Brothers and Sisters: Age-Group Progression for Children and Youth We desire to strengthen our beloved children and youth through increased faith in Jesus Christ, deeper understanding of His gospel, and greater unity with His Church and its members. To that end, we are pleased to announce that in January 2019 children will complete Primary and begin attending Sunday School and Young Women or Aaronic Priesthood quorums as age- groups atth e beginning of January in the year they turn 12. Likewise, young women will progress between Young Women classes and young men between Aaronic Priesthood quorums as age- groups at the beginning of January in the year they turn 14 and 16. In addition, young men will be eligible for ordinationto the appropriate priesthood office in January of the year they tum 12, 14, and 16. Young women and ordained young men will be eligible for limited-use temple recommends beginning in January of the year they turn 12. Ordination to a priesthood office for young men and obtaining a limited-use temple recommend for young women and young men will continue to be individual matters, based on worthiness, readiness, and personal circumstances. Ordinations and obtaining limited-use recommends will typically take place throughout January. -

Journal of Mormon History Vol. 22, No. 1, 1996

Journal of Mormon History Volume 22 Issue 1 Article 1 1996 Journal of Mormon History Vol. 22, No. 1, 1996 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation (1996) "Journal of Mormon History Vol. 22, No. 1, 1996," Journal of Mormon History: Vol. 22 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory/vol22/iss1/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Mormon History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Mormon History Vol. 22, No. 1, 1996 Table of Contents CONTENTS ARTICLES PRESIDENTIAL ADDRESS • --The Emergence of Mormon Power since 1945 Mario S. De Pillis, 1 TANNER LECTURE • --The Mormon Nation and the American Empire D. W. Meinig, 33 • --Labor and the Construction of the Logan Temple, 1877-84 Noel A. Carmack, 52 • --From Men to Boys: LDS Aaronic Priesthood Offices, 1829-1996 William G. Hartley, 80 • --Ernest L. Wilkinson and the Office of Church Commissioner of Education Gary James Bergera, 137 • --Fanny Alger Smith Custer: Mormonism's First Plural Wife? Todd Compton, 174 REVIEWS --James B. Allen, Jessie L. Embry, Kahlile B. Mehr. Hearts Turned to the Fathers: A History of the Genealogical Society of Utah, 1894-1994 Raymonds. Wright, 208 --S. Kent Brown, Donald Q. Cannon, Richard H.Jackson, eds. Historical Atlas of Mormonism Lowell C. "Ben"Bennion, 212 --Spencer J. Palmer and Shirley H. -

Gospel Taboo.Indd

John the Baptist Chariot Elder Jesus Race Missionary Baptize Horse Priesthood Locust Rome Melchizedek Honey Wheels Aaronic Personal Progress Temptation Bride Young Women Devil Groom Book Satan Wedding Goal Evil Marry Set Bad White Bishop Meeting Holy Ward Together Clean Leader Have Pure Conduct Gather Consecrated Father Sacrament Temple Gospel Cumorah Faith Preach Hill Believe Christ Moroni Knowledge Missionary Joseph Smith Hope Teach Pageant Value Branch Leprosy Idol Small White Worship Ward Skin Superstition Stake Disease False Church Leper God Joseph Peace Patience Jesus War Virtue Father Calm Calm Carpenter Still Wait Mary Hate Kids Honesty Terrestrial Stake Truth Celestial Ward Lie Telestial Group Trustworthy Glory Region Integrity Three Area Repentance Manna Job Sorry Bread Bible Forgive White Suffer Bad Moses Man Ask Israel Satan Carthage Jail Modesty Lazarus Joseph Smith Clothes Martha Martyr Cover Mary Hyrum Smith Dress Dead Kill Wear Jesus Deseret Charity Atonement Lovely Love Christ Honey Bee Service Pay Saints Help Sins Pioneers Understanding Gethsemane Refreshments Golden Rule Resurrection Food Do Body Cookies Others Christ Punch Treat First Meeting Be Dead Easter Eternity Abinadi Holiday Infi nity Book of Mormon Bunny Forever Fire Eggs Endless Prophet Basket Seal Man Noah Fast Relief Society Ark Food Sister Rain Sunday Women Forty Eat Sunday Animals Hungry Priesthood Eve Teacher Commandment Adam Instructor Ten Eden Student Moses Woman Learn Tablets Apple School Rules Devil Patriarch Spirit Satan Blessing Holy Ghost Lucifer -

The Aaronic Priesthood— Greater Than You Might Think a Message About Duty to God

YOUTH By David L. Beck Young Men General President The Aaronic Priesthood— Greater Than You Might Think A MESSagE ABOUT DUty TO GOD our years ago I attended a Lord has called you to a wonderful memorial service for my brother work, and He expects you to be a FGary. One of the speakers paid priesthood man. a great tribute to my brother. I have been thinking about it ever since. He The Greatness of the said, “Gary was a priesthood man. Aaronic Priesthood . He understood the priesthood, Just think about the greatness of honored the priesthood, and fully the Aaronic Priesthood that you bear: embraced the priesthood and its • The Lord sent the resurrected principles.” John the Baptist to restore the When my brother died, he was Aaronic Priesthood. When a high priest in the Melchizedek John conferred this priest- Priesthood, and he had enjoyed 50 hood on Joseph Smith and years of priesthood service. Gary was Oliver Cowdery, he called a loving husband and father who had them his “fellow servants” served an honorable full-time mis- (D&C 13:1). President sion, married in the temple, magnified Gordon B. Hinckley his priesthood callings, and served (1910–2008) pointed out diligently as a home teacher. that John “did not place IRI You are an Aaronic Priesthood himself above Joseph and © D holder. Your priesthood service is just Oliver. He put them on beginning. You may not even have his same level when he 50 days of priesthood experience yet. addressed them as ‘my fel- But you can be worthy of the same low servants.’” President tribute Gary received. -

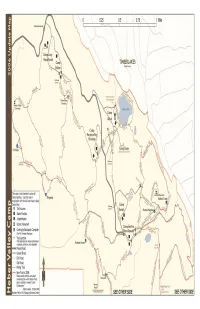

485861 Map.Pdf

Camp Abish Legacy Building Lake Staff Office Cabin Camp Host Restroom/Shower e d c n Campsite 1 n a a y r t Staff Quarters a n w e k r p a Volleyball m P Food Prep Building a y c e l Campsite 2 l a Pavilion V Garbage r e b e H Tent Site Campsite 3 o t Small Tent Site For Priesthood Leaders Campsite 4 A bis h T rail Campfire Ring Amphitheater Trailhead p d n m a a Paved Road r C e d w e o e Gravel Road d R a e p S M a m Dirt Road r l i a e i ra a T s C h Campsite 5 y le o k T o c o t r in Hiking Trail a H M i l Camp Path il ra T y BYU Mapping Services to Camp Hinckley and le to Challenge Course and ck Geography Department Camp Esther Hin Camp Sariah to Heber Valley Parkway S to camp entrance a to Camp Abish to Camp Abish to Camp Abish r i Legacy Lake Legacy Lake This map does not completely a Legacy Lake l h rai T T ow p r Sn cover the Heber Valley Camp. a i l a A Please use this Map together Campsite 3 b is M h T with your Heber Valley Camp ra Volleyball il a Map. e r Trailhead l ai Tr A w Camp Snow Cabin no l S Restroom/Shower a r Food Prep Building t Campsite 2 il ra n Campsite 1 T Garbage Dumpster k e e re Amphitheater C Priesthood Tent Site den C Hid Campfire Ring 9 Challenge Missionary Residence 0 Course 2 Buildings 0 New trails in 2009 2 BACKCOUNTRY HIKERS: The following trails are being realigned, rebuilt, or eliminated: - Bald Knoll Ridge Trail Challenge Course 5 - Crows Nest Trail - Crows Nest Loop - Hidden Creek Trail S Ab a ish r T i r - Shepherd Trail a ai h Camp Rebekah l T Campsite 6 - Eagle Loop Trail r a i l Amphitheater Challenge Course Campsite 5 Parking Please contact your Camp Host or Trail Host for detailed information before hiking in the Upper Camp area. -

Roger Terry, “Authority and Priesthood in the LDS Church, Part 1: Definitions and Development,”

ARTICLES AND ESSAYS AUTHORITY AND PRIESTHOOD IN THE LDS CHURCH, PART 1: DEFINITIONS AND DEVELOPMENT Roger Terry The issue of authority in Mormonism became painfully public with the rise of the Ordain Women movement. The Church can attempt to blame (and discipline) certain individuals, but this development is a lot larger than any one person or group of people. The status of women in the Church was basically a time bomb ticking down to zero. With the strides toward equality American society has taken over the past sev- eral decades, it was really just a matter of time before the widening gap between social circumstances in general and conditions in Mormondom became too large to ignore. When the bomb finally exploded, the Church scrambled to give credible explanations, but most of these responses have felt inadequate at best. The result is a good deal of genuine pain and a host of very valid questions that have proven virtually impossible to answer satisfactorily. At least in my mind, this unfolding predicament has raised certain important questions about what priesthood really is and how it cor- responds to the larger idea of authority. What is this thing that women are denied? What is this thing that, for over a century, faithful black LDS men were denied? Would clarifying or fine-tuning our definition—or even better understanding the history of how our current definition developed—perhaps change the way we regard priesthood, the way we practice it, the way we bestow it, or refuse to bestow it? The odd sense I have about priesthood, after a good deal of study and pondering, is 1 2 Dialogue, Spring 2018 that most of us don’t really have a clear idea of what it is and how it has evolved over the years. -

The Role and Function of the Seventies in LDS Church History

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 1960 The Role and Function of the Seventies in LDS Church History James N. Baumgarten Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Cultural History Commons, and the Mormon Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Baumgarten, James N., "The Role and Function of the Seventies in LDS Church History" (1960). Theses and Dissertations. 4513. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/4513 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. 3 e F tebeebTHB ROLEROLB ardaindANDAIRD FUNCTION OF tebeebTHB SEVKMTIBS IN LJSlasLDS chweceweCHMECHURCH HISTORYWIRY A thesis presentedsenteddented to the dedepartmentA nt of history brigham youngyouyom university in partial ftlfillmeutrulfilliaent of the requirements for the degree master of arts by jalejamsjamejames N baumgartenbelbexbaxaartgart9arten august 1960 TABLE CFOF CcontentsCOBTEHTS part I1 introductionductionreductionroductionro and theology chapter bagragpag ieI1 introduction explanationN ionlon of priesthood and revrevelationlation Sutsukstatementement of problem position of the writer dedelimitationitationcitation of thesis method of procedure and sources II11 church doctrine on the seventies 8 ancient origins the revelation -

Representations of Mormonism in American Culture Jeremy R

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository American Studies ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 8-19-2011 Imagining the Saints: Representations of Mormonism in American Culture Jeremy R. Ricketts Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/amst_etds Part of the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Ricketts, eJ remy R.. "Imagining the Saints: Representations of Mormonism in American Culture." (2011). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/amst_etds/37 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in American Studies ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Jeremy R. Ricketts Candidate American Studies Departmelll This dissertation is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Dissertation Commillee: , Chairperson Alex Lubin, PhD &/I ;Se, tJ_ ,1-t C- 02-s,) Lori Beaman, PhD ii IMAGINING THE SAINTS: REPRESENTATIONS OF MORMONISM IN AMERICAN CULTURE BY JEREMY R. RICKETTS B. A., English and History, University of Memphis, 1997 M.A., University of Alabama, 2000 M.Ed., College Student Affairs, 2004 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy American Studies The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico May 2011 iii ©2011, Jeremy R. Ricketts iv DEDICATION To my family, in the broadest sense of the word v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation has been many years in the making, and would not have been possible without the assistance of many people. My dissertation committee has provided invaluable guidance during my time at the University of New Mexico (UNM). -

Hagoth and the Polynesian Tradition

Hagoth and the Polynesian Tradition Jerry K. Loveland n what amounts to an aside in the story of the Book of Mormon I peoples, there is in the 63rd chapter of Alma a brief reference to a “curious man” named Hagoth. And it came to pass that Hagoth, he being an exceedingly curi- ous man, therefore he went forth and built him an exceedingly large ship, on the borders of the land Bountiful, by the land Desolation, and launched it into the west sea, by the narrow neck which led into the land northward. And behold, there were many of the Nephites who did enter therein and did sail forth with much provisions, and also many women and children; and they took their course northward. And thus ended the thirty and seventh year. And in the thirty and eighth year, this man built other ships. And the first ship did also return, and many more people did enter into it; and they also took much provisions, and set out again to the land northward. And it came to pass that they were never heard of more. And we suppose that they were drowned in the depths of the sea. And it came to pass that one other ship also did sail forth; and whither she went we know not. (Alma 3:5–8) What we have here, is an account of a colonizing movement of men, women, and children who went out in ships presumably into the Pacific Ocean sometime between 53 and 57 b.c. And they were never heard of again. -

Imperial Zions: Mormons, Polygamy, and the Politics of Domesticity in the Nineteenth Century

Imperial Zions: Mormons, Polygamy, and the Politics of Domesticity in the Nineteenth Century By Amanda Lee Hendrix-Komoto A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Professor Susan M. Juster, Co-Chair Associate Professor Damon I. Salesa, Co-Chair Professor Terryl L. Givens Associate Professor Kali A.K. Israel Professor Mary C. Kelley ii To my grandmother Naomi, my mother Linda, my sisters Laura and Jessica, and my daughter Eleanor iii Acknowledgements This is a dissertation about family and the relationships that people form with each other in order to support themselves during difficult times. It seems right, then, to begin by acknowledging the kinship network that has made this dissertation possible. Susan Juster was an extraordinary advisor. She read multiple drafts of the dissertation, provided advice on how to balance motherhood and academia, and, through it all, demonstrated how to be an excellent role model to future scholars. I will always be grateful for her support and mentorship. Likewise, Damon Salesa has been a wonderful co-chair. His comments on a seminar paper led me to my dissertation topic. Because of him, I think more critically about race. In my first years of graduate school, Kali Israel guided me through the politics of being a working-class woman at an elite academic institution. Even though my work took me far afield from her scholarship, she constantly sent me small snippets of information. Through her grace and generosity, Mary Kelley served as a model of what it means to be a female scholar.