Roger Terry, “Authority and Priesthood in the LDS Church, Part 1: Definitions and Development,”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Secret Mormon Meetings of 1922

University of Nevada, Reno THE SECRET MORMON MEETINGS OF 1922 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History By Shannon Caldwell Montez C. Elizabeth Raymond, Ph.D. / Thesis Advisor December 2019 Copyright by Shannon Caldwell Montez 2019 All Rights Reserved UNIVERSITY OF NEVADA RENO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by SHANNON CALDWELL MONTEZ entitled The Secret Mormon Meetings of 1922 be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS C. Elizabeth Raymond, Ph.D., Advisor Cameron B. Strang, Ph.D., Committee Member Greta E. de Jong, Ph.D., Committee Member Erin E. Stiles, Ph.D., Graduate School Representative David W. Zeh, Ph.D., Dean, Graduate School December 2019 i Abstract B. H. Roberts presented information to the leadership of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in January of 1922 that fundamentally challenged the entire premise of their religious beliefs. New research shows that in addition to church leadership, this information was also presented during the neXt few months to a select group of highly educated Mormon men and women outside of church hierarchy. This group represented many aspects of Mormon belief, different areas of eXpertise, and varying approaches to dealing with challenging information. Their stories create a beautiful tapestry of Mormon life in the transition years from polygamy, frontier life, and resistance to statehood, assimilation, and respectability. A study of the people involved illuminates an important, overlooked, underappreciated, and eXciting period of Mormon history. -

Stories from General Conference PRIESTHOOD POWER, VOL. 2

Episode 27 Stories from General Conference PRIESTHOOD POWER, VOL. 2 NARRATOR: This is Stories from General Conference, volume two, on the topic of Priesthood Power. You are listening to the Mormon Channel. Worthy young men in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints have the privilege of receiving the Aaronic Priesthood. This allows them to belong to a quorum where they learn to serve and administer in some of the ordinances of the Church. In the April 1997 General Priesthood Meeting, Elder David B. Haight reminisced about his youth and how the priesthood helped him progress. (Elder David B. Haight, Priesthood Session, April 1997) “Those of you who are young today--and I'm thinking of the deacons who are assembled in meetings throughout the world--I remember when I was ordained a deacon by Bishop Adams. He took the place of my father when he died. My father baptized me, but he wasn't there when I received the Aaronic Priesthood. I remember the thrill that I had when I became a deacon and now held the priesthood, as they explained to me in a simple way and simple language that I had received the power to help in the organization and the moving forward of the Lord's program upon the earth. We receive that as 12-year-old boys. We go through those early ranks of the lesser priesthood--a deacon, a teacher, and then a priest--learning little by little, here a little and there a little, growing in knowledge and wisdom. That little testimony that you start out with begins to grow, and you see it magnifying and you see it building in a way that is understandable to you. -

December 14, 2018 To: General Authorities; General Auxiliary Presidencies; Area Seventies; Stake, Mission, District, and Temple

THE CHURCH OF JESUS GHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS OFFICE OF THE FIRST PRESIDENCY 47 EAST SOUTH TEMPLE STREET, SALT LAKE 0ITY, UTAH 84150-1200 December 14, 2018 To: General Authorities; General Auxiliary Presidencies; Area Seventies; Stake, Mission, District, andTemple Presidents; Bishops and Branch Presidents; Stake, District, Ward,and Branch Councils (To be read in sacrament meeting) Dear Brothers and Sisters: Age-Group Progression for Children and Youth We desire to strengthen our beloved children and youth through increased faith in Jesus Christ, deeper understanding of His gospel, and greater unity with His Church and its members. To that end, we are pleased to announce that in January 2019 children will complete Primary and begin attending Sunday School and Young Women or Aaronic Priesthood quorums as age- groups atth e beginning of January in the year they turn 12. Likewise, young women will progress between Young Women classes and young men between Aaronic Priesthood quorums as age- groups at the beginning of January in the year they turn 14 and 16. In addition, young men will be eligible for ordinationto the appropriate priesthood office in January of the year they tum 12, 14, and 16. Young women and ordained young men will be eligible for limited-use temple recommends beginning in January of the year they turn 12. Ordination to a priesthood office for young men and obtaining a limited-use temple recommend for young women and young men will continue to be individual matters, based on worthiness, readiness, and personal circumstances. Ordinations and obtaining limited-use recommends will typically take place throughout January. -

Journal of Mormon History Vol. 22, No. 1, 1996

Journal of Mormon History Volume 22 Issue 1 Article 1 1996 Journal of Mormon History Vol. 22, No. 1, 1996 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation (1996) "Journal of Mormon History Vol. 22, No. 1, 1996," Journal of Mormon History: Vol. 22 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory/vol22/iss1/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Mormon History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Mormon History Vol. 22, No. 1, 1996 Table of Contents CONTENTS ARTICLES PRESIDENTIAL ADDRESS • --The Emergence of Mormon Power since 1945 Mario S. De Pillis, 1 TANNER LECTURE • --The Mormon Nation and the American Empire D. W. Meinig, 33 • --Labor and the Construction of the Logan Temple, 1877-84 Noel A. Carmack, 52 • --From Men to Boys: LDS Aaronic Priesthood Offices, 1829-1996 William G. Hartley, 80 • --Ernest L. Wilkinson and the Office of Church Commissioner of Education Gary James Bergera, 137 • --Fanny Alger Smith Custer: Mormonism's First Plural Wife? Todd Compton, 174 REVIEWS --James B. Allen, Jessie L. Embry, Kahlile B. Mehr. Hearts Turned to the Fathers: A History of the Genealogical Society of Utah, 1894-1994 Raymonds. Wright, 208 --S. Kent Brown, Donald Q. Cannon, Richard H.Jackson, eds. Historical Atlas of Mormonism Lowell C. "Ben"Bennion, 212 --Spencer J. Palmer and Shirley H. -

Gospel Taboo.Indd

John the Baptist Chariot Elder Jesus Race Missionary Baptize Horse Priesthood Locust Rome Melchizedek Honey Wheels Aaronic Personal Progress Temptation Bride Young Women Devil Groom Book Satan Wedding Goal Evil Marry Set Bad White Bishop Meeting Holy Ward Together Clean Leader Have Pure Conduct Gather Consecrated Father Sacrament Temple Gospel Cumorah Faith Preach Hill Believe Christ Moroni Knowledge Missionary Joseph Smith Hope Teach Pageant Value Branch Leprosy Idol Small White Worship Ward Skin Superstition Stake Disease False Church Leper God Joseph Peace Patience Jesus War Virtue Father Calm Calm Carpenter Still Wait Mary Hate Kids Honesty Terrestrial Stake Truth Celestial Ward Lie Telestial Group Trustworthy Glory Region Integrity Three Area Repentance Manna Job Sorry Bread Bible Forgive White Suffer Bad Moses Man Ask Israel Satan Carthage Jail Modesty Lazarus Joseph Smith Clothes Martha Martyr Cover Mary Hyrum Smith Dress Dead Kill Wear Jesus Deseret Charity Atonement Lovely Love Christ Honey Bee Service Pay Saints Help Sins Pioneers Understanding Gethsemane Refreshments Golden Rule Resurrection Food Do Body Cookies Others Christ Punch Treat First Meeting Be Dead Easter Eternity Abinadi Holiday Infi nity Book of Mormon Bunny Forever Fire Eggs Endless Prophet Basket Seal Man Noah Fast Relief Society Ark Food Sister Rain Sunday Women Forty Eat Sunday Animals Hungry Priesthood Eve Teacher Commandment Adam Instructor Ten Eden Student Moses Woman Learn Tablets Apple School Rules Devil Patriarch Spirit Satan Blessing Holy Ghost Lucifer -

The Aaronic Priesthood— Greater Than You Might Think a Message About Duty to God

YOUTH By David L. Beck Young Men General President The Aaronic Priesthood— Greater Than You Might Think A MESSagE ABOUT DUty TO GOD our years ago I attended a Lord has called you to a wonderful memorial service for my brother work, and He expects you to be a FGary. One of the speakers paid priesthood man. a great tribute to my brother. I have been thinking about it ever since. He The Greatness of the said, “Gary was a priesthood man. Aaronic Priesthood . He understood the priesthood, Just think about the greatness of honored the priesthood, and fully the Aaronic Priesthood that you bear: embraced the priesthood and its • The Lord sent the resurrected principles.” John the Baptist to restore the When my brother died, he was Aaronic Priesthood. When a high priest in the Melchizedek John conferred this priest- Priesthood, and he had enjoyed 50 hood on Joseph Smith and years of priesthood service. Gary was Oliver Cowdery, he called a loving husband and father who had them his “fellow servants” served an honorable full-time mis- (D&C 13:1). President sion, married in the temple, magnified Gordon B. Hinckley his priesthood callings, and served (1910–2008) pointed out diligently as a home teacher. that John “did not place IRI You are an Aaronic Priesthood himself above Joseph and © D holder. Your priesthood service is just Oliver. He put them on beginning. You may not even have his same level when he 50 days of priesthood experience yet. addressed them as ‘my fel- But you can be worthy of the same low servants.’” President tribute Gary received. -

485861 Map.Pdf

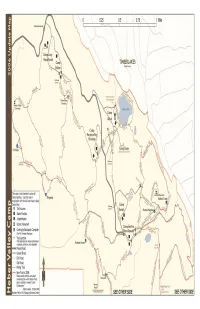

Camp Abish Legacy Building Lake Staff Office Cabin Camp Host Restroom/Shower e d c n Campsite 1 n a a y r t Staff Quarters a n w e k r p a Volleyball m P Food Prep Building a y c e l Campsite 2 l a Pavilion V Garbage r e b e H Tent Site Campsite 3 o t Small Tent Site For Priesthood Leaders Campsite 4 A bis h T rail Campfire Ring Amphitheater Trailhead p d n m a a Paved Road r C e d w e o e Gravel Road d R a e p S M a m Dirt Road r l i a e i ra a T s C h Campsite 5 y le o k T o c o t r in Hiking Trail a H M i l Camp Path il ra T y BYU Mapping Services to Camp Hinckley and le to Challenge Course and ck Geography Department Camp Esther Hin Camp Sariah to Heber Valley Parkway S to camp entrance a to Camp Abish to Camp Abish to Camp Abish r i Legacy Lake Legacy Lake This map does not completely a Legacy Lake l h rai T T ow p r Sn cover the Heber Valley Camp. a i l a A Please use this Map together Campsite 3 b is M h T with your Heber Valley Camp ra Volleyball il a Map. e r Trailhead l ai Tr A w Camp Snow Cabin no l S Restroom/Shower a r Food Prep Building t Campsite 2 il ra n Campsite 1 T Garbage Dumpster k e e re Amphitheater C Priesthood Tent Site den C Hid Campfire Ring 9 Challenge Missionary Residence 0 Course 2 Buildings 0 New trails in 2009 2 BACKCOUNTRY HIKERS: The following trails are being realigned, rebuilt, or eliminated: - Bald Knoll Ridge Trail Challenge Course 5 - Crows Nest Trail - Crows Nest Loop - Hidden Creek Trail S Ab a ish r T i r - Shepherd Trail a ai h Camp Rebekah l T Campsite 6 - Eagle Loop Trail r a i l Amphitheater Challenge Course Campsite 5 Parking Please contact your Camp Host or Trail Host for detailed information before hiking in the Upper Camp area. -

Journal of Mormon History Vol. 20, No. 1, 1994

Journal of Mormon History Volume 20 Issue 1 Article 1 1994 Journal of Mormon History Vol. 20, No. 1, 1994 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation (1994) "Journal of Mormon History Vol. 20, No. 1, 1994," Journal of Mormon History: Vol. 20 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory/vol20/iss1/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Mormon History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Mormon History Vol. 20, No. 1, 1994 Table of Contents LETTERS vi ARTICLES PRESIDENTIAL ADDRESS • --Positivism or Subjectivism? Some Reflections on a Mormon Historical Dilemma Marvin S. Hill, 1 TANNER LECTURE • --Mormon and Methodist: Popular Religion in the Crucible of the Free Market Nathan O. Hatch, 24 • --The Windows of Heaven Revisited: The 1899 Tithing Reformation E. Jay Bell, 45 • --Plurality, Patriarchy, and the Priestess: Zina D. H. Young's Nauvoo Marriages Martha Sonntag Bradley and Mary Brown Firmage Woodward, 84 • --Lords of Creation: Polygamy, the Abrahamic Household, and Mormon Patriarchy B. Cannon Hardy, 119 REVIEWS 153 --The Story of the Latter-day Saints by James B. Allen and Glen M. Leonard Richard E. Bennett --Hero or Traitor: A Biographical Story of Charles Wesley Wandell by Marjorie Newton Richard L. Saunders --Mormon Redress Petition: Documents of the 1833-1838 Missouri Conflict edited by Clark V. Johnson Stephen C. -

A Study of the History of the Office of High Priest

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2006-07-18 A Study of the History of the Office of High Priest John D. Lawson Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the History of Christianity Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Lawson, John D., "A Study of the History of the Office of High Priest" (2006). Theses and Dissertations. 749. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/749 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. A STUDY OF THE HISTORY OF THE OFFICE OF HIGH PRIEST by John Lawson A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts Religious Education Brigham Young University July 2006 Copyright © 2006 John D. Lawson All Rights Reserved ii BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY GRADUATE COMMITTEE APPROVAL Of a thesis submitted by John D. Lawson This thesis has been read by each member of the following graduate committee and has been found to be satisfactory. ___________________________ ____________________________________ Date Craig J. Ostler, Chair ___________________________ ____________________________________ Date Joseph F. McConkie ___________________________ ____________________________________ Date Guy L. Dorius iii BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY As chair of the candidate’s graduate committee, I have read the thesis of John D. Lawson in its final form and have found that (1) its format, citations, and bibliographical style are consistent and acceptable and fulfill university and department style requirements; (2) its illustrative materials including figures, tables, and charts are in place; and (3) the final manuscript is satisfactory to the graduate committee and is ready for submission to the university library. -

The Role and Function of the Seventies in LDS Church History

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 1960 The Role and Function of the Seventies in LDS Church History James N. Baumgarten Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Cultural History Commons, and the Mormon Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Baumgarten, James N., "The Role and Function of the Seventies in LDS Church History" (1960). Theses and Dissertations. 4513. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/4513 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. 3 e F tebeebTHB ROLEROLB ardaindANDAIRD FUNCTION OF tebeebTHB SEVKMTIBS IN LJSlasLDS chweceweCHMECHURCH HISTORYWIRY A thesis presentedsenteddented to the dedepartmentA nt of history brigham youngyouyom university in partial ftlfillmeutrulfilliaent of the requirements for the degree master of arts by jalejamsjamejames N baumgartenbelbexbaxaartgart9arten august 1960 TABLE CFOF CcontentsCOBTEHTS part I1 introductionductionreductionroductionro and theology chapter bagragpag ieI1 introduction explanationN ionlon of priesthood and revrevelationlation Sutsukstatementement of problem position of the writer dedelimitationitationcitation of thesis method of procedure and sources II11 church doctrine on the seventies 8 ancient origins the revelation -

The Geographies of Maori-Mormonism and the Creation

Western Geography, 15/16 (2005/2006), pp. 108–122 ©Western Division, Canadian Association of Geographers Student Writing The Geographies of Maori–Mormonism and the Creation of a Cross-Cultural Hybrid Matthew Summerskill Geography Program University of Northern British Columbia Prince George, BC V2N 4Z9 This paper explores how the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints attracted a large Maori following in late 19th century New Zealand, and examines key fea- tures of Maori–Mormonism at this time. It focuses on how the alienation of Maori lands during the New Zealand Wars led to Maori resistance of British-based religion. Mormonism attracted Maori because it was non-British, fulfilled Maori prophecies, coincided with some pre-existing Maori values, and provided Maori an inspiring ancestral path. However Maori also resisted attacks that Mormon missionaries launched on aspects of their traditional culture. This paper suggests that newly produced Maori–Mormon (hybrid) spaces were largely shaped by Mormon missionaries’ embracement of ‘acceptable’ Maori culture, and missionary attempts to undercut Maori traditions that conflicted with Latter-day Saint doctrines. Introduction In New Zealand, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has often been called a Maori church (Barber & Gilgen, 1996; Britsch, 1986). Likewise, Latter-day Saints have always prided The Geographies of Maori–Mormonism 109 themselves for their success in attracting Maori to the Mormon Church—particularly where other churches have failed (Lineham, 1991). Why is it that Mormonism has such a strong Maori follow- ing, and when did it gain authenticity among the Maori? For the Mormon mission, was it a case of being in the right place at the right time? Or was it that Mormonism offered more to the Maori way of life than we might expect? This paper examines the means by which Maori were drawn to Mormonism (i.e., land grievances, prophecies, and cultural compatibility), and places a particular emphasis on the concept of hybridity. -

Criptural Commentary

through faith: "The Priests in Christendom warn their flocks not to believe in Mormonism; and yet you sisters have power to heal the sick, by the laying on of hands, which they cannot do." (Millenial Star, XV:130.) criptural Commentary In the early history of the Church it was common for Relief Society sisters to visit and administer relief to their kindred sisters, not through the priesthood but by virtue of their Priesthood callings and faith. Steven F. Christensen not in me, how can it pass through to the patient? And how do we get it in us? We Another saying which some sisters In this issue of commentary we will live worthy of it, and the Lord is anxious may enjoy placing next to their other discuss some interesting items to see that we have it. Brigham Young "refrigerator slogans" is: "We have pertaining to priesthood. Extracts said, "I do not say that I heal everybody I heard of men who have said to their have been chosen which might lay hands on; but many have been healed wives, ’I hold the priesthood and interest the reader to pursue the under my administration." (Discourses of you’ve got to do what I say.’ Such a study personally. Brigham Young, comp. John A. Widstoe [Salt Lake City: Deseret Book Co., 1954], p. man should be tried for his Power in the Priesthood 162)... membership. Certainly he should not Readers no doubt will be familiar with James E. Talmage, in acknowledging be honored in his priesthood. We rule LDS terminology which sometimes the injustice experienced or felt by in love and understanding." (Spencer speaks of those who have been given some has written: W.