Control of Breathing in Mechanically Ventilated Patients

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Infections of the Respiratory Tract

F70954-07.qxd 12/10/02 7:36 AM Page 71 Infections of the respiratory 7 tract the nasal hairs and by inertial impaction with mucus- 7.1 Pathogenesis 71 covered surfaces in the posterior nasopharynx (Fig. 11). 7.2 Diagnosis 72 The epiglottis, its closure reflex and the cough reflex all reduce the risk of microorganisms reaching the lower 7.3 Management 72 respiratory tract. Particles small enough to reach the tra- 7.4 Diseases and syndromes 73 chea and bronchi stick to the respiratory mucus lining their walls and are propelled towards the oropharynx 7.5 Organisms 79 by the action of cilia (the ‘mucociliary escalator’). Self-assessment: questions 80 Antimicrobial factors present in respiratory secretions further disable inhaled microorganisms. They include Self-assessment: answers 83 lysozyme, lactoferrin and secretory IgA. Particles in the size range 5–10 µm may penetrate further into the lungs and even reach the alveolar air Overview spaces. Here, alveolar macrophages are available to phagocytose potential pathogens, and if these are overwhelmed neutrophils can be recruited via the This chapter deals with infections of structures that constitute inflammatory response. The defences of the respira- the upper and lower respiratory tract. The general population tory tract are a reflection of its vulnerability to micro- commonly experiences upper respiratory tract infections, bial attack. Acquisition of microbial pathogens is which are often seen in general practice. Lower respiratory tract infections are less common but are more likely to cause serious illness and death. Diagnosis and specific chemotherapy of respiratory tract infections present a particular challenge to both the clinician and the laboratory staff. -

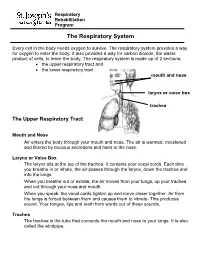

The Respiratory System

Respiratory Rehabilitation Program The Respiratory System Every cell in the body needs oxygen to survive. The respiratory system provides a way for oxygen to enter the body. It also provides a way for carbon dioxide, the waste product of cells, to leave the body. The respiratory system is made up of 2 sections: the upper respiratory tract and the lower respiratory tract mouth and nose larynx or voice box trachea The Upper Respiratory Tract Mouth and Nose Air enters the body through your mouth and nose. The air is warmed, moistened and filtered by mucous secretions and hairs in the nose. Larynx or Voice Box The larynx sits at the top of the trachea. It contains your vocal cords. Each time you breathe in or inhale, the air passes through the larynx, down the trachea and into the lungs. When you breathe out or exhale, the air moves from your lungs, up your trachea and out through your nose and mouth. When you speak, the vocal cords tighten up and move closer together. Air from the lungs is forced between them and causes them to vibrate. This produces sound. Your tongue, lips and teeth form words out of these sounds. Trachea The trachea is the tube that connects the mouth and nose to your lungs. It is also called the windpipe. The Lower Respiratory Tract Inside Lungs Outside Lungs bronchial tubes alveoli diaphragm (muscle) Bronchial Tubes The trachea splits into 2 bronchial tubes in your lungs. These are called the left bronchus and right bronchus. The bronchus tubes keep branching off into smaller and smaller tubes called bronchi. -

RESPIRATORY TRACT INFECTIONS Peter Zajac, DO, FACOFP, Author Amy J

OFP PATIENT EDUCATION HANDOUT RESPIRATORY TRACT INFECTIONS Peter Zajac, DO, FACOFP, Author Amy J. Keenum, DO, PharmD, Editor • Ronald Januchowski, DO, FACOFP, Health Literacy Editor HOME MANAGEMENT INCLUDES: • Drinking plenty of clear fuids and rest. Vitamin-C may help boost your immune system. Over-the-counter pain relievers such as acetaminophen and ibuprofen can be helpful for fevers and to ease any aches. Saline (salt) nose drops, lozenges, and vapor rubs can also help symptoms when used as directed by your physician. • A cool mist humidifer can make breathing easier by thinning mucus. • If you smoke, you should try to stop smoking for good! Avoid second-hand smoking also. • In most cases, antibiotics are not recommended because they are only effective if bacteria caused the infection. • Other treatments, that your Osteopathic Family Physician may prescribe, include Osteopathic Manipulative Therapy (OMT). OMT can help clear mucus, Respiratory tract infections are any relieve congestion, improve breathing and enhance comfort, relaxation, and infection that affect the nose, sinuses, immune function. and throat (i.e. the upper respiratory tract) or airways and lungs (i.e. the • Generally, the symptoms of a respiratory tract infection usually pass within lower respiratory tract). Viruses are one to two weeks. the main cause of the infections, but • To prevent spreading infections, sneeze into the arm of your shirt or in a tissue. bacteria can cause some. You can Also, practice good hygiene such as regularly washing your hands with soap and spread the infection to others through warm water. Wipe down common surfaces, such as door knobs and faucet handles, the air when you sneeze or cough. -

Respiratory Tract Infections in the Tropics

9.1 CHAPTER 9 Respiratory Tract Infections in the Tropics Tim J.J. Inglis 9.1 INTRODUCTION Acute respiratory infections are the single most common infective cause of death worldwide. This is also the case in the tropics, where they are a major cause of death in children under five. Bacterial pneumonia is particularly common in children in the tropics, and is more often lethal. Pulmonary tuberculosis is the single most common fatal infection and is more prevalent in many parts of the tropics due to a combination of endemic HIV infection and widespread poverty. A lack of diagnostic tests, limited access to effective treatment and some traditional healing practices exacerbate the impact of respiratory infection in tropical communities. The rapid urbanisation of populations in the tropics has increased the risk of transmitting respiratory pathogens. A combination of poverty and overcrowding in the peri- urban zones of rapidly expanding tropical cities promotes the epidemic spread of acute respiratory infection. PART A. INFECTIONS OF THE LOWER RESPIRATORY TRACT 9.2 PNEUMONIA 9.2.1 Frequency Over four million people die from acute respiratory infection per annum, mostly in developing countries. There is considerable overlap between these respiratory deaths and deaths due to tuberculosis, the single commonest fatal infection. The frequency of acute respiratory infection differs with location due to host, pathogen and environmental factors. Detailed figures are difficult to find and often need to be interpreted carefully, even for tuberculosis where data collection is more consistent. But in urban settings the enormity of respiratory infection is clearly evident. Up to half the patients attending hospital outpatient departments in developing countries have an acute respiratory infection. -

Introduction to the Respiratory System

C h a p t e r 15 The Respiratory System PowerPoint® Lecture Slides prepared by Jason LaPres Lone Star College - North Harris Copyright © 2010 Pearson Education, Inc. Copyright © 2010 Pearson Education, Inc. Introduction to the Respiratory System • The Respiratory System – Cells produce energy: • For maintenance, growth, defense, and division • Through mechanisms that use oxygen and produce carbon dioxide Copyright © 2010 Pearson Education, Inc. Introduction to the Respiratory System • Oxygen – Is obtained from the air by diffusion across delicate exchange surfaces of the lungs – Is carried to cells by the cardiovascular system, which also returns carbon dioxide to the lungs Copyright © 2010 Pearson Education, Inc. 15-1 The respiratory system, composed of conducting and respiratory portions, has several basic functions Copyright © 2010 Pearson Education, Inc. Functions of the Respiratory System • Provides extensive gas exchange surface area between air and circulating blood • Moves air to and from exchange surfaces of lungs • Protects respiratory surfaces from outside environment • Produces sounds • Participates in olfactory sense Copyright © 2010 Pearson Education, Inc. Components of the Respiratory System • The Respiratory Tract – Consists of a conducting portion • From nasal cavity to terminal bronchioles – Consists of a respiratory portion • The respiratory bronchioles and alveoli The Respiratory Tract Copyright © 2010 Pearson Education, Inc. Components of the Respiratory System • Alveoli – Are air-filled pockets within the lungs: -

4 Lower Respiratory Disease

d:/postscript/04-CHAP4_4.3D – 27/1/4 – 9:27 [This page: 245] 4 Lower Respiratory Disease S Walters and DJ Ward 1 Executive summary Statement of the problem Respiratory disease has a substantial impact on the health of populations at all ages and every level of morbidity. Acute upper respiratory infections are the commonest illnesses experienced by individuals throughout life, accounting for over 27% of all GP consultations. Asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease are the cause of almost 5% of all admissions and bed-days, and lower respiratory infections are responsible for almost 11% of deaths. While still uncommon, TB rates appear to be rising and it remains an important problem in some communities. Cystic fibrosis is the commonest inherited disorder in the UK and is an important cause of death in young adults. Improvements in survival mean increasing use of expensive medications and medical technologies. Sub-categories The principal sub-categories of lower respiratory disease considered in this review were chosen on the basis of their public health or health service impact, and are: 1 lower respiratory infections in children 2 lower respiratory infections in adults, including pneumonia 3 asthma 4 chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) 5 tuberculosis 6 cystic fibrosis. Upper respiratory conditions (including allergic rhinitis), influenza, lung cancer, neonatal respiratory problems, occupational diseases, sleep-disordered breathing, diffuse parenchymal lung disease (a wide range of conditions that include fibrosing alveolitis and sarcoidosis) and other respiratory disorders are not specifically reviewed in detail in this revision. Together, these conditions account for 7% of deaths and 2.5% of hospital admissions, and form a substantial part of the workload of respiratory physicians. -

The Respiratory System

Respiratory Rehabilitation Program The Respiratory System Every cell in the body needs oxygen to survive. The respiratory system provides a way for oxygen to enter the body. It also provides a way for carbon dioxide, the waste product of cells, to leave the body. The respiratory system is made up of 2 sections: • the upper respiratory tract and • the lower respiratory tract mouth and nose larynx or voice box trachea The Upper Respiratory Tract Mouth and Nose Air enters the body through your mouth and nose. The air is warmed, moistened and filtered by mucous secretions and hairs in the nose. Larynx or Voice Box The larynx sits at the top of the trachea. It contains your vocal cords. Each time you breathe in or inhale, the air passes through the larynx, down the trachea and into the lungs. When you breathe out or exhale, the air moves from your lungs, up your trachea and out through your nose and mouth. When you speak, the vocal cords tighten up and move closer together. Air from the lungs is forced between them and causes them to vibrate. This produces sound. Your tongue, lips and teeth form words out of these sounds. Trachea The trachea is the tube that connects the mouth and nose to your lungs. It is also called the windpipe. You can feel some of your trachea in the front of your neck. It feels firm with tough rings around it. The Lower Respiratory Tract Inside Lungs Outside Lungs bronchial tubes alveoli diaphragm (muscle) Bronchial Tubes The trachea splits into 2 bronchial tubes in your lungs. -

Dysbiosis in Pediatrics Is Associated with Respiratory Infections: Is There a Place for Bacterial-Derived Products?

microorganisms Review Dysbiosis in Pediatrics Is Associated with Respiratory Infections: Is There a Place for Bacterial-Derived Products? Stefania Ballarini 1,*, Giovanni A. Rossi 2, Nicola Principi 3 and Susanna Esposito 4 1 Department of Experimental Medicine, University of Perugia, Didactic Pole “Sant’Andrea delle Fratte”, 06132 Perugia, Italy 2 Unit of Pediatric Pulmonary, G. Gaslini University Hospital, 16147 Genoa, Italy; [email protected] 3 Università degli Studi di Milano, 20122 Milan, Italy; [email protected] 4 Department of Medicine and Surgery, Pediatric Clinic, University of Parma, 43126 Parma, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Respiratory tract infections (RTIs) are common in childhood because of the physiologic immaturity of the immune system, a microbial community under development in addition to other genetic, physiological, environmental and social factors. RTIs tend to recur and severe lower viral RTIs in early childhood are not uncommon and are associated with increased risk of respiratory disorders later in life, including recurrent wheezing and asthma. Therefore, a better understanding of the main players and mechanisms involved in respiratory morbidity is necessary for a prompt and improved care as well as for primary prevention. The inter-talks between human immune components and microbiota as well as their main functions have been recently unraveled; nevertheless, more is still to be discovered or understood in the above medical conditions. The aim of this review paper is to provide the most up-to-date overview on dysbiosis in pre-school children and its association with Citation: Ballarini, S.; Rossi, G.A.; RTIs and their complications. -

Health Effects Classification and Its Role in the Derivation of Minimal Risk Levels: Respiratory Effects

1. Clean Technol., Environ. Toxicol., & Occup. Med., Vol. 7, No.3, 1998 233 HEALTH EFFECTS CLASSIFICATION AND ITS ROLE IN THE DERIVATION OF MINIMAL RISK LEVELS: RESPIRATORY EFFECTS SHARON B. WILBUR Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry Department of Health and Human Services Atlanta, Georgia The anatomy and physiology ofthe respiratory system as related to pathophysiology of the respiratory system are considered. The various toxicological end points in the respiratory system and the relative seriousness ofthe effects are discussed. The impact ofassessing the seriousness of the effects on the derivation of health-based guidance values, with specific examples ofthe Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry's minimal risk levels based on respiratory effects, is presented. INTRODUCTION To determine the levels of significant human exposure to a given chemical and associated health effects, the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry's (ATSDR's) toxicological profiles examine and interpret available toxicological and epidemiological data. The respiratory system is an important consideration from a public health standpoint because it is a primary target for hazardous substances and represents the first contact for inhaled pollutants. Respiratory effects can occur from inhalation oftoxic gases, vapors, dusts, or aerosols ofparticulate or liquid chemicals or solutions. In addition, chemicals present in the systemic circulation from exposure by other routes can reach the lungs and elicit toxic effects therein. Respiratory tract tissue can be damaged directly by the chemical or indirectly by its metabolites, since many cells in the respiratory system are capable of xenobiotic metabolism. Many respiratory effects of toxic chemicals are due to excessive oxidative burden on the lungs, leading to chronic bronchitis, emphysema, and fibrosis, for example. -

Diagnosis and Treatment of Respiratory Illness in Children and Adults Non-Infectious Rhinitis Algorithm

Health Care Guideline: Diagnosis and Treatment of Respiratory Illness in Children and Adults Non-Infectious Rhinitis Algorithm Patient presents with symptoms of non-infectious rhinitis History/physical Consider RAST* and skin yes testing when definitive Signs and symptoms no Signs and symptoms Consider referral to diagnosis is needed suggest allergic suggest structural specialist etiology? etiology? yes no * Radioallergosorbent test Treatment options Non-allergic • Education on avoidance rhinitis • Medications - Intranasal corticosteroids - Intranasal antihistamines - Oral antihistamines Treatment options - Combination intranasal • Medications antihistamines/intranasal corticosteroids - Intranasal antihistamines - Leukotriene blockers - Decongestants - Anticholinergics - Intranasal corticosteroids - Decongestants - Intranasal ipraptropium bromide • Patient education Adequate yes • Patient education Adequate yes • Follow-up as response? • Follow-up as appropriate response? appropriate no no Consider referral • Consider testing to a specialist • Consider referral to a specialist www.icsi.org Copyright © 2017 by Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement 1 Diagnosis and Treatment of Respiratory Illness in Children and Adults Fifth Edition/September 2017 Acute Pharyngitis Algorithm Patient presents with symptoms of GAS* pharyngitis History/physical Shared decision-making Consider strep testing Do not routinely test if Centor (RADT**, throat culture, criteria < 3 or when viral features PCR***) based on clinical like rhinorrhea, cough, oral -

Bovine Respiratory Disease (BRD) Causes Increased Death Losses As Well As Medication Costs, Labor, and Lost Production

BOVINE RESPIRATORY Animal Health Fact Sheet DISEASE Clell V. Bagley, DVM, Extension Veterinarian Utah State University, Logan UT 84322-5600 July 1997 AH/Beef/04 Disease of the respiratory tract is a major problem for cattle and it continues to cause serious economic losses for producers. Bovine respiratory disease (BRD) causes increased death losses as well as medication costs, labor, and lost production. Many different infectious agents may cause similar clinical signs. Multiple agents are often involved in the development of BRD. DISEASE CONDITIONS (OR SYNDROMES) The respiratory diseases of cattle can be divided into three main categories: 1. Upper respiratory tract infections These infections cause inflammation of the nostrils, throat (pharynx) and windpipe (trachea). The clinical signs are usually mild and involve coughing, nasal discharge, fever, and a decreased appetite. 2. Diphtheria This infection involves the larynx (voice box) and may occur alone or along with other respiratory infections. There are often loud noises during breathing and the swelling may severely restrict the air flow and result in death of the animal. 3. Pneumonia (lower respiratory tract infection) An infection of the lungs is often due to an extension of infection from the upper respiratory tract (#1) or a failure of the mechanisms which are designed to protect the lungs. It is much more serious and causes more severe signs than does an upper respiratory infection. Shipping fever is one form of lower respiratory tract disease and derives its name from the usual occurrence of the disease shortly after shipment of the cattle. CAUSES AND DEVELOPMENT OF DISEASE The causes of BRD are multiple and complex, but the three factors of stress, viral infection and bacterial infection are almost always involved in cases of severe disease. -

Pulmonary Ventilation

CHAPTER 2 Pulmonary Ventilation © IT Stock/Polka Dot/ inkstock Chapter Objectives By studying this chapter, you should be able to do Name two things that cause pleural pressure the following: to decrease. 8. Describe the mechanics of ventilation with 1. Identify the basic structures of the conducting respect to the changes in pulmonary pressures. and respiratory zones of the ventilation system. 9. Identify the muscles involved in inspiration and 2. Explain the role of minute ventilation and its expiration at rest. relationship to the function of the heart in the 10. Describe the partial pressures of oxygen and production of energy at the tissues. carbon dioxide in the alveoli, lung capillaries, 3. Identify the diff erent ways in which carbon tissue capillaries, and tissues. dioxide is transported from the tissues to the 11. Describe how carbon dioxide is transported in lungs. the blood. 4. Explain the respiratory advantage of breathing 12. Explain the significance of the oxygen– depth versus rate during a treadmill exercise. hemoglobin dissociation curve. 5. Describe the composition of ambient air and 13. Discuss the eff ects of decreasing pH, increasing alveolar air and the pressure changes in the pleu- temperature, and increasing 2,3-diphosphoglyc- ral and pulmonary spaces. erate on the HbO dissociation curve. 6. Diagram the three ways in which carbon dioxide 2 14. Distinguish between and explain external res- is transported in the venous blood to the lungs. piration and internal respiration. 7. Defi ne pleural pressure. What happens to alve- olar volume when pleural pressure decreases? Chapter Outline Pulmonary Structure and Function Pulmonary Volumes and Capacities Anatomy of Ventilation Lung Volumes and Capacities Lungs Pulmonary Ventilation Mechanics of Ventilation Minute Ventilation Inspiration Alveolar Ventilation Expiration Pressure Changes Copyright ©2014 Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC, an Ascend Learning Company Content not final.