AIRWAY MANAGEMENT: HYPE ABOUT VENTILATION and the ANETHETIZED PATIENT Donna M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Stethoscope: Some Preliminary Investigations

695 ORIGINAL ARTICLE The stethoscope: some preliminary investigations P D Welsby, G Parry, D Smith Postgrad Med J: first published as on 5 January 2004. Downloaded from ............................................................................................................................... See end of article for Postgrad Med J 2003;79:695–698 authors’ affiliations ....................... Correspondence to: Dr Philip D Welsby, Western General Hospital, Edinburgh EH4 2XU, UK; [email protected] Submitted 21 April 2003 Textbooks, clinicians, and medical teachers differ as to whether the stethoscope bell or diaphragm should Accepted 30 June 2003 be used for auscultating respiratory sounds at the chest wall. Logic and our results suggest that stethoscope ....................... diaphragms are more appropriate. HISTORICAL ASPECTS note is increased as the amplitude of the sound rises, Hippocrates advised ‘‘immediate auscultation’’ (the applica- resulting in masking of higher frequency components by tion of the ear to the patient’s chest) to hear ‘‘transmitted lower frequencies—‘‘turning up the volume accentuates the sounds from within’’. However, in 1816 a French doctor, base’’ as anyone with teenage children will have noted. Rene´The´ophile Hyacinth Laennec invented the stethoscope,1 Breath sounds are generated by turbulent air flow in the which thereafter became the identity symbol of the physician. trachea and proximal bronchi. Airflow in the small airways Laennec apparently had observed two children sending and alveoli is of lower velocity and laminar in type and is 6 signals to each other by scraping one end of a long piece of therefore silent. What is heard at the chest wall depends on solid wood with a pin, and listening with an ear pressed to the conductive and filtering effect of lung tissue and the the other end.2 Later, in 1816, Laennec was called to a young characteristics of the chest wall. -

Infections of the Respiratory Tract

F70954-07.qxd 12/10/02 7:36 AM Page 71 Infections of the respiratory 7 tract the nasal hairs and by inertial impaction with mucus- 7.1 Pathogenesis 71 covered surfaces in the posterior nasopharynx (Fig. 11). 7.2 Diagnosis 72 The epiglottis, its closure reflex and the cough reflex all reduce the risk of microorganisms reaching the lower 7.3 Management 72 respiratory tract. Particles small enough to reach the tra- 7.4 Diseases and syndromes 73 chea and bronchi stick to the respiratory mucus lining their walls and are propelled towards the oropharynx 7.5 Organisms 79 by the action of cilia (the ‘mucociliary escalator’). Self-assessment: questions 80 Antimicrobial factors present in respiratory secretions further disable inhaled microorganisms. They include Self-assessment: answers 83 lysozyme, lactoferrin and secretory IgA. Particles in the size range 5–10 µm may penetrate further into the lungs and even reach the alveolar air Overview spaces. Here, alveolar macrophages are available to phagocytose potential pathogens, and if these are overwhelmed neutrophils can be recruited via the This chapter deals with infections of structures that constitute inflammatory response. The defences of the respira- the upper and lower respiratory tract. The general population tory tract are a reflection of its vulnerability to micro- commonly experiences upper respiratory tract infections, bial attack. Acquisition of microbial pathogens is which are often seen in general practice. Lower respiratory tract infections are less common but are more likely to cause serious illness and death. Diagnosis and specific chemotherapy of respiratory tract infections present a particular challenge to both the clinician and the laboratory staff. -

The Physiology of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation

Society for Critical Care Anesthesiologists Section Editor: Avery Tung E REVIEW ARTICLE CME The Physiology of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Keith G. Lurie, MD, Edward C. Nemergut, MD, Demetris Yannopoulos, MD, and Michael Sweeney, MD * † ‡ § Outcomes after cardiac arrest remain poor more than a half a century after closed chest cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) was first described. This review article is focused on recent insights into the physiology of blood flow to the heart and brain during CPR. Over the past 20 years, a greater understanding of heart–brain–lung interactions has resulted in novel resuscitation methods and technologies that significantly improve outcomes from cardiac arrest. This article highlights the importance of attention to CPR quality, recent approaches to regulate intrathoracic pressure to improve cerebral and systemic perfusion, and ongo- ing research related to the ways to mitigate reperfusion injury during CPR. Taken together, these new approaches in adult and pediatric patients provide an innovative, physiologically based road map to increase survival and quality of life after cardiac arrest. (Anesth Analg 2016;122:767–83) udden cardiac arrest remains a leading cause of pre- during CPR, and new approaches to reduce injury associ- hospital and in-hospital death.1 Efforts to resuscitate ated with reperfusion.3,5–8,10–48 Given the debate surrounding patients after cardiac arrest have preoccupied scien- what is known, what we think we know, and what remains S 1,2 tists and clinicians for decades. However, the majority unknown about resuscitation science, this article also pro- of patients are never successfully resuscitated.1,3–5 Based vides some contrarian and nihilistic points of view. -

Maximum Expiratory Flow Rates in Induced Bronchoconstriction in Man

Maximum expiratory flow rates in induced bronchoconstriction in man A. Bouhuys, … , B. M. Kim, A. Zapletal J Clin Invest. 1969;48(6):1159-1168. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI106073. Research Article We evaluated changes of maximum expiratory flow-volume (MEFV) curves and of partial expiratory flow-volume (PEFV) curves caused by bronchoconstrictor drugs and dust, and compared these to the reverse changes induced by a bronchodilator drug in previously bronchoconstricted subjects. Measurements of maximum flow at constant lung inflation (i.e. liters thoracic gas volume) showed larger changes, both after constriction and after dilation, than measurements of peak expiratory flow rate, 1 sec forced expiratory volume and the slope of the effort-independent portion of MEFV curves. Changes of flow rates on PEFV curves (made after inspiration to mid-vital capacity) were usually larger than those of flow rates on MEFV curves (made after inspiration to total lung capacity). The decreased maximum flow rates after constrictor agents are not caused by changes in lung static recoil force and are attributed to narrowing of small airways, i.e., airways which are uncompressed during forced expirations. Changes of maximum expiratory flow rates at constant lung inflation (e.g. 60% of the control total lung capacity) provide an objective and sensitive measurement of changes in airway caliber which remains valid if total lung capacity is altered during treatment. Find the latest version: https://jci.me/106073/pdf Maximum Expiratory Flow Rates in Induced Bronchoconstriction in Man A. Bouiuys, V. R. HuNTr, B. M. Kim, and A. ZAPLETAL From the John B. Pierce Foundation Laboratory and the Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut 06510 A B S T R A C T We evaluated changes of maximum ex- rates are best studied as a function of lung volume. -

Monitoring Anesthetic Depth

ANESTHETIC MONITORING Lyon Lee DVM PhD DACVA MONITORING ANESTHETIC DEPTH • The central nervous system is progressively depressed under general anesthesia. • Different stages of anesthesia will accompany different physiological reflexes and responses (see table below, Guedel’s signs and stages). Table 1. Guedel’s (1937) Signs and Stages of Anesthesia based on ‘Ether’ anesthesia in cats. Stages Description 1 Inducement, excitement, pupils constricted, voluntary struggling Obtunded reflexes, pupil diameters start to dilate, still excited, 2 involuntary struggling 3 Planes There are three planes- light, medium, and deep More decreased reflexes, pupils constricted, brisk palpebral reflex, Light corneal reflex, absence of swallowing reflex, lacrimation still present, no involuntary muscle movement. Ideal plane for most invasive procedures, pupils dilated, loss of pain, Medium loss of palpebral reflex, corneal reflexes present. Respiratory depression, severe muscle relaxation, bradycardia, no Deep (early overdose) reflexes (palpebral, corneal), pupils dilated Very deep anesthesia. Respiration ceases, cardiovascular function 4 depresses and death ensues immediately. • Due to arrival of newer inhalation anesthetics and concurrent use of injectable anesthetics and neuromuscular blockers the above classic signs do not fit well in most circumstances. • Modern concept has two stages simply dividing it into ‘awake’ and ‘unconscious’. • One should recognize and familiarize the reflexes with different physiologic signs to avoid any untoward side effects and complications • The system must be continuously monitored, and not neglected in favor of other signs of anesthesia. • Take all the information into account, not just one sign of anesthetic depth. • A major problem faced by all anesthetists is to avoid both ‘too light’ anesthesia with the risk of sudden violent movement and the dangerous ‘too deep’ anesthesia stage. -

Introduction to Airway Resistance Measurements

Introduction to airway resistance measurements Dr. David Kaminsky Department of Medicine The University of Vermont VT 05405 Burlington UNITED STATES OF AMERICA [email protected] AIMS Review physiology of airway resistance Survey measures of airway resistance Provide examples of clinical applications Highlight research applications SUMMARY Airway resistance (Raw) is one of the fundamental features of the mechanics of the respiratory system. While the flow-volume loop offers insight into the volume and flow of air, it is limited in terms of specific information regarding lung mechanics. Airway resistance is the ratio of driving pressure divided by flow through the airways. It specifies the pressure required to achieve a flow of air with a velocity of 1L/sec. If the airway is represented by a simple, rigid tube, with laminar flow of air through it, the airway resistance Raw = (8 x L x )/ r4, where L = length of the tube, = viscosity of the gas, and r = radius of the tube. It is important to note that the r4 relationship demonstrates how sensitive resistance is to the size of the tube, varying inversely with the 4th power of the radius. The inner diameter of the airway is itself determined by many factors, including airway smooth muscle contractile state, airway wall thickness (related to inflammation, edema and remodeling), airway wall buckling and formation of mucosal folds, the interdependence, or linkage, of airway and surrounding lung parenchyma, and the intrinsic elastic recoil of the lung parenchyma, which serves as a load on the airway and variably resists bronchoconstriction. Of course, the airways are not rigid tubes, and in fact flow is a complex process involving both laminar and turbulent conditions, so this calculation of Raw is an approximation only. -

Den170044 Summary

DE NOVO CLASSIFICATION REQUEST FOR CLEARMATE REGULATORY INFORMATION FDA identifies this generic type of device as: Isocapnic ventilation device. An isocapnic ventilation device is a prescription device used to administer a blend of carbon dioxide and oxygen gases to a patient to induce hyperventilation. This device may be labeled for use with breathing circuits made of reservoir bags (21 CFR 868.5320), oxygen cannulas (21 CFR 868.5340), masks (21 CFR 868.5550), valves (21 CFR 868.5870), resuscitation bags (21 CFR 868.5915), and/or tubing (21 CFR 868.5925). NEW REGULATION NUMBER: 21 CFR 868.5480 CLASSIFICATION: Class II PRODUCT CODE: QFB BACKGROUND DEVICE NAME: ClearMateTM SUBMISSION NUMBER: DEN170044 DATE OF DE NOVO: August 23, 2017 CONTACT: Thornhill Research, Inc. 5369 W. Wallace Ave Scottsdale, AZ 85254 INDICATIONS FOR USE ClearMateTM is intended to be used by emergency department medical professionals as an adjunctive treatment for patients suffering from carbon monoxide poisoning. The use of ClearMateTM enables accelerated elimination of carbon monoxide from the body by allowing isocapnic hyperventilation through simulated partial rebreathing. LIMITATIONS Intended Patient Population is adults aged greater than 16 years old and a minimum of 40 kg (80.8 lbs) ClearMateTM is intended to be used by emergency department medical professionals. This device should always be used as adjunctive therapy; not intended to replace existing protocol for treating carbon monoxide poisoning. When providing treatment to a non-spontaneously breathing patient using the ClearMate™ non-spontaneous breathing patient circuit, CO2 monitoring equipment for the measurement of expiratory carbon dioxide concentration must be used. PLEASE REFER TO THE LABELING FOR A MORE COMPLETE LIST OF WARNINGS AND CAUTIONS. -

Hyperoxia-Induced Pulmonary Vascular and Lung Abnormalities in Young Rats and Potential for Recovery

003 1-399818511910-1059$02.00/0 PEDIATRIC RESEARCH Vol. 19, No. 10, 1985 Copyright O 1985 International Pediatric Research Foundation, Inc. Prinfed in U.S.A. Hyperoxia-Induced Pulmonary Vascular and Lung Abnormalities in Young Rats and Potential for Recovery WENDY LEE WILSON, MICHELLE MULLEN, PETER M. OLLEY, AND MARLENE RABINOVITCH Departments of Cardiology and Pathology, Research Institute, The Hospital for Sick Children and Departments of Pediatrics and Pathology, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada ABSTRACT. We carried out morphometric studies to The newborn infant, especially the premature with hyaline assess the effects of increasing durations of hyperoxic membrane disease, may require prolonged high oxygen therapy. exposure on the developing rat lung and to evaluate the Hyperoxia is damaging to lung tissue presumably because the potential for new growth and for regression of structural relatively inert O2 molecule undergoes univalent reduction to abnormalities on return to room air. From day 10 of life form highly reactive free radicals which are cytotoxic (1). Some Sprague-Dawley rats were either exposed to hyperoxia protection is afforded by the antioxidant enzyme systems of the (0.8F102) for 2-8 wk or were removed after 2 wk and lungs, superoxide dismutase, catalase, and glutathione peroxidase allowed to "recover" in room air for 2-6 wk. Litter mates (2-5) but the induction of these enzymes is often insufficient to maintained in room air served as age matched controls. prevent tissue damage. In the clinical setting it has been difficult Every 2 wk experimental and control rats from each group to separate the role of oxygen toxicity from other variables such were weighed and killed. -

Relationship Between PCO 2 and Unfavorable Outcome in Infants With

nature publishing group Articles Clinical Investigation Relationship between PCO2 and unfavorable outcome in infants with moderate-to-severe hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy Krithika Lingappan1, Jeffrey R. Kaiser2, Chandra Srinivasan3, Alistair J. Gunn4; on behalf of the CoolCap Study Group BACKGROUND: Abnormal PCO2 is common in infants with term infants with HIE, both minimum and cumulative expo- hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy (HIE). The objective was to sure to hypocapnia in the first 12 h of the trial were associated determine whether hypocapnia was independently associated with death or adverse neurodevelopmental outcome (13). The with unfavorable outcome (death or severe neurodevelopmen- dose–response relationship between PCO2 and outcome for tal disability at 18 mo) in infants with moderate-to-severe HIE. infants with moderate-to-severe HIE is unknown. METHODS: This was a post hoc analysis of the CoolCap Study The risk of developing hypocapnia or hypercapnia may be in which infants were randomized to head cooling or standard affected by severity of brain injury, intensity and duration of care. Blood gases were measured at prespecified times after newborn resuscitation, timing after the primary injury, and/or randomization. PCO2 and follow-up data were available for 196 response to metabolic acidosis. Thus, in this secondary analy- of 234 infants. Analyses were performed to investigate the rela- sis of the CoolCap Study (14), we sought to confirm the obser- tionship between hypocapnia in the first 72 h after randomiza- vation that -

BTS Guideline for Oxygen Use in Adults in Healthcare and Emergency

BTS guideline BTS guideline for oxygen use in adults in healthcare Thorax: first published as 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2016-209729 on 15 May 2017. Downloaded from and emergency settings BRO’Driscoll,1,2 L S Howard,3 J Earis,4 V Mak,5 on behalf of the British Thoracic Society Emergency Oxygen Guideline Group ▸ Additional material is EXECUTIVE SUMMARY OF THE GUIDELINE appropriate oxygen therapy can be started in the published online only. To view Philosophy of the guideline event of unexpected clinical deterioration with please visit the journal online ▸ (http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/ Oxygen is a treatment for hypoxaemia, not hypoxaemia and also to ensure that the oxim- thoraxjnl-2016-209729). breathlessness. Oxygen has not been proven to etry section of the early warning score (EWS) 1 have any consistent effect on the sensation of can be scored appropriately. Respiratory Medicine, Salford ▸ Royal Foundation NHS Trust, breathlessness in non-hypoxaemic patients. The target saturation should be written (or Salford, UK ▸ The essence of this guideline can be summarised ringed) on the drug chart or entered in an elec- 2Manchester Academic Health simply as a requirement for oxygen to be prescribed tronic prescribing system (guidance on figure 1 Sciences Centre (MAHSC), according to a target saturation range and for those (chart 1)). Manchester, UK 3Hammersmith Hospital, who administer oxygen therapy to monitor the Imperial College Healthcare patient and keep within the target saturation range. 3 Oxygen administration NHS Trust, London, UK ▸ The guideline recommends aiming to achieve ▸ Oxygen should be administered by staff who are 4 University of Liverpool, normal or near-normal oxygen saturation for all trained in oxygen administration. -

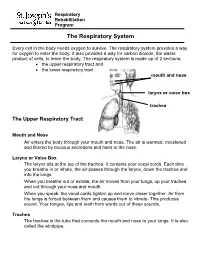

The Respiratory System

Respiratory Rehabilitation Program The Respiratory System Every cell in the body needs oxygen to survive. The respiratory system provides a way for oxygen to enter the body. It also provides a way for carbon dioxide, the waste product of cells, to leave the body. The respiratory system is made up of 2 sections: the upper respiratory tract and the lower respiratory tract mouth and nose larynx or voice box trachea The Upper Respiratory Tract Mouth and Nose Air enters the body through your mouth and nose. The air is warmed, moistened and filtered by mucous secretions and hairs in the nose. Larynx or Voice Box The larynx sits at the top of the trachea. It contains your vocal cords. Each time you breathe in or inhale, the air passes through the larynx, down the trachea and into the lungs. When you breathe out or exhale, the air moves from your lungs, up your trachea and out through your nose and mouth. When you speak, the vocal cords tighten up and move closer together. Air from the lungs is forced between them and causes them to vibrate. This produces sound. Your tongue, lips and teeth form words out of these sounds. Trachea The trachea is the tube that connects the mouth and nose to your lungs. It is also called the windpipe. The Lower Respiratory Tract Inside Lungs Outside Lungs bronchial tubes alveoli diaphragm (muscle) Bronchial Tubes The trachea splits into 2 bronchial tubes in your lungs. These are called the left bronchus and right bronchus. The bronchus tubes keep branching off into smaller and smaller tubes called bronchi. -

Influence of a Six-Week Swimming Training with Added Respiratory

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article Influence of a Six-Week Swimming Training with Added Respiratory Dead Space on Respiratory Muscle Strength and Pulmonary Function in Recreational Swimmers Stefan Szczepan 1,* , Natalia Danek 2 , Kamil Michalik 2 , Zofia Wróblewska 3 and Krystyna Zato ´n 1 1 Department of Swimming, Faculty of Physical Education, University School of Physical Education in Wroclaw, Ignacego Jana Paderewskiego 35, Swimming Pool, 51-612 Wroclaw, Poland; [email protected] 2 Department of Physiology and Biochemistry, Faculty of Physical Education, University School of Physical Education in Wroclaw, Ignacego Jana Paderewskiego 35, P-3 Building, 51-612 Wroclaw, Poland; [email protected] (N.D.); [email protected] (K.M.) 3 Faculty of Pure and Applied Mathematics, Wroclaw University of Science and Technology, Zygmunta Janiszewskiego 14a, C-11 Building, 50-372 Wroclaw, Poland; zofi[email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +48-713-473-404 Received: 5 July 2020; Accepted: 6 August 2020; Published: 8 August 2020 Abstract: The avoidance of respiratory muscle fatigue and its repercussions may play an important role in swimmers’ health and physical performance. Thus, the aim of this study was to investigate whether a six-week moderate-intensity swimming intervention with added respiratory dead space (ARDS) resulted in any differences in respiratory muscle variables and pulmonary function in recreational swimmers. A sample of 22 individuals (recreational swimmers) were divided into an experimental (E) and a control (C) group, observed for maximal oxygen uptake (VO2max). The intervention involved 50 min of front crawl swimming performed at 60% VO2max twice weekly for six weeks.