Health Effects Classification and Its Role in the Derivation of Minimal Risk Levels: Respiratory Effects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Case Report: What Is the Real Cause of Death from Acute Chlorine Exposure in an Asthmatic Patient? Toprak S1 and Kalkan EA2*

Toprak and Kalkan. Int J Respir Pulm Med 2016, 3:045 International Journal of Volume 3 | Issue 2 ISSN: 2378-3516 Respiratory and Pulmonary Medicine Case Report: Open Access A Case Report: What is the Real Cause of Death from Acute Chlorine Exposure in an Asthmatic Patient? Toprak S1 and Kalkan EA2* 1Forensic Medicine Department, Bulent Ecevit University, Turkey 2Forensic Medicine Department, Canakkale Onsekiz Mart University, Turkey *Corresponding author: Esin Akgul Kalkan, MD, Assistant Professor, Canakkale Onsekiz Mart University, Faculty of Medicine, Forensic Medicine Department, Canakkale Onsekiz Mart Universitesi, Tip Fakultesi, Adli Tip Anabilim Dali, 17020, Canakkale, Turkey, Tel: +90 532 511 12 97, +90 286 218 00 18/2777, E-mail: [email protected] with a mixture of various chemicals including bleach and an acid Abstract containing product (hydrochloric acid). According to witnesses, her This case report presents an acute and chronic inflammation symptoms include cough, shortness of breath along with red tearing process at the same time and resulted in death following exposure eyes. She is a non-smoker and has no significant medical history other to chlorine gas. A 65-years-old woman died shortly after cleaning than asthma. She was declared dead when she arrives to hospital. her bathroom with a mixture of various chemicals including bleach and an acid containing product. She was declared dead when she The decedent was 155 cm tall and weighed 67 kg. The external arrives to hospital. She is a non-smoker and has no significant findings were unremarkable. Internally the left and right lungs medical history other than asthma. -

Job Hazard Analysis

Identifying and Evaluating Hazards in Research Laboratories Guidelines developed by the Hazards Identification and Evaluation Task Force of the American Chemical Society’s Committee on Chemical Safety Copyright 2013 American Chemical Society Table of Contents FOREWORD ................................................................................................................................................... 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................................................................. 5 Task Force Members ..................................................................................................................................... 6 1. SCOPE AND APPLICATION ..................................................................................................................... 7 2. DEFINITIONS .......................................................................................................................................... 7 3. HAZARDS IDENTIFICATION AND EVALUATION ................................................................................... 10 4. ESTABLISHING ROLES AND RESPONSIBILITIES .................................................................................... 14 5. CHOOSING AND USING A TECHNIQUE FROM THIS GUIDE ................................................................. 17 6. CHANGE CONTROL .............................................................................................................................. 19 7. ASSESSING -

Infections of the Respiratory Tract

F70954-07.qxd 12/10/02 7:36 AM Page 71 Infections of the respiratory 7 tract the nasal hairs and by inertial impaction with mucus- 7.1 Pathogenesis 71 covered surfaces in the posterior nasopharynx (Fig. 11). 7.2 Diagnosis 72 The epiglottis, its closure reflex and the cough reflex all reduce the risk of microorganisms reaching the lower 7.3 Management 72 respiratory tract. Particles small enough to reach the tra- 7.4 Diseases and syndromes 73 chea and bronchi stick to the respiratory mucus lining their walls and are propelled towards the oropharynx 7.5 Organisms 79 by the action of cilia (the ‘mucociliary escalator’). Self-assessment: questions 80 Antimicrobial factors present in respiratory secretions further disable inhaled microorganisms. They include Self-assessment: answers 83 lysozyme, lactoferrin and secretory IgA. Particles in the size range 5–10 µm may penetrate further into the lungs and even reach the alveolar air Overview spaces. Here, alveolar macrophages are available to phagocytose potential pathogens, and if these are overwhelmed neutrophils can be recruited via the This chapter deals with infections of structures that constitute inflammatory response. The defences of the respira- the upper and lower respiratory tract. The general population tory tract are a reflection of its vulnerability to micro- commonly experiences upper respiratory tract infections, bial attack. Acquisition of microbial pathogens is which are often seen in general practice. Lower respiratory tract infections are less common but are more likely to cause serious illness and death. Diagnosis and specific chemotherapy of respiratory tract infections present a particular challenge to both the clinician and the laboratory staff. -

Gas Exchange

Gas exchange Gas exchange occurs as a result of respiration, when carbon dioxide is excreted and oxygen taken up, and photosynthesis, when oxygen is excreted and carbon dioxide is taken up. The rate of gas exchange is affected by: • the area available for diffusion • the distance over which diffusion occurs • the concentration gradient across the gas exchange surface • the speed with which molecules diffuse through membranes. Efficient gas exchange systems must: • have a large surface area to volume ratio • be thin • have mechanisms for maintaining steep concentration gradients across themselves • be permeable to gases. Single-celled organisms are aquatic and their cell surface membrane has a sufficiently large surface area to volume ratio to act as an efficient gas exchange surface. In larger organisms, permeable, thin, flat structures have all the properties of efficient gas exchange surfaces but need water to prevent their dehydration and give them mechanical support. Since the solubility of oxygen in water is low, organisms that obtain their oxygen from water can maintain only a low metabolic rate. In small and thin organisms, the distance from gas exchange surface to the inside of the organism is short enough for diffusion of gases to be efficient. Diffusion gradients are maintained because gases are continually used up or produced. In larger organisms, simple diffusion is not an efficient way of transporting gases between cells in the body and the gas exchange surface. In many animals a blood circulatory system carries gases to and from the gas exchange surface. The gas-carrying capacity of the blood is increased by respiratory pigments, such as haemoglobin. -

Mechanisms of Pulmonary Gas Exchange Abnormalities During Experimental Group B Streptococcal Infusion

003 I -3998/85/1909-0922$02.00/0 PEDIATRIC RESEARCH Vol. 19, No. 9, I985 Copyright 0 1985 International Pediatric Research Foundation, Inc. Printed in (I.S. A. Mechanisms of Pulmonary Gas Exchange Abnormalities during Experimental Group B Streptococcal Infusion GREGORY K. SORENSEN, GREGORY J. REDDING, AND WILLIAM E. TRUOG ABSTRACT. Group B streptococcal sepsis in newborns obtained from GBS (5, 6). Arterial Poz fell by 9 torr in association produces pulmonary arterial hypertension and hypoxemia. with the increase in pulmonary arterial pressure (4). In contrast, The purpose of this study was to investigate the mecha- the neonatal piglet infused with GBS demonstrated both pul- nisms by which hypoxemia occurs. Ten anesthetized, ven- monary arterial hypertension and profound arterial hypoxemia tilated piglets were infused with 2 x lo9 colony forming (7). These results suggest that the neonatal pulmonary vascula- unitstkg of Group B streptococci over a 30-min period. ture may respond to bacteremia differently from that of adults. Pulmonary arterial pressure rose from 14 ? 2.8 to 38 ? The relationship between Ppa and the matching of alveolar 6.7 torr after 20 min of the bacterial infusion (p< 0.01). ventilation and pulmonary perfusion, a major determinant of During the same period, cardiac output fell from 295 to arterial oxygenation during room air breathing (8), has not been 184 ml/kg/min (p< 0.02). Arterial Po2 declined from 97 studied in newborns. The predictable rise in Ppa with an infusion 2 7 to 56 2 11 torr (p< 0.02) and mixed venous Po2 fell of group B streptococcus offers an opportunity to delineate the from 39.6 2 5 to 28 2 8 torr (p< 0.05). -

CARBON MONOXIDE: the SILENT KILLER Information You Should

CARBON MONOXIDE: THE SILENT KILLER Information You Should Know Carbon monoxide is a silent killer that can lurk within fossil fuel burning household appliances. Many types of equipment and appliances burn different types of fuel to provide heat, cook, generate electricity, power vehicles and various tools, such as chain saws, weed eaters and leaf blowers. When these units operate properly, they use fresh air for combustion and vent or exhaust carbon dioxide. When fresh air is restricted, through improper ventilation, the units create carbon monoxide, which can saturate the air inside the structure. Carbon Monoxide can be lethal when accidentally inhaled in concentrated doses. Such a situation is referred to as carbon monoxide poisoning. This is a serious condition that is a medical emergency that should be taken care of right away. What Is It? Carbon monoxide, often abbreviated as CO, is a gas produced by burning fossil fuel. What makes it such a silent killer is that it is odorless and colorless. It is extremely difficult to detect until the body has inhaled a detrimental amount of the gas, and if inhaled in high concentrations, it can be fatal. Carbon monoxide causes tissue damage by blocking the body’s ability to absorb enough oxygen. In fact, poisoning from this gas is one of the leading causes of unintentional death from poison. Common Sources of CO Kerosene or fuel-based heaters Fireplaces Gasoline powered equipment and generators Charcoal grills Automobile exhaust Portable generators Tobacco smoke Chimneys, furnaces, and boilers Gas water heaters Wood stoves and gas stoves Properly installed and maintained appliances are safe and efficient. -

Gas-Liquid Hollow Fiber Membrane Contactors for Different Applications

Review Gas-Liquid Hollow Fiber Membrane Contactors for Different Applications Stepan D. Bazhenov 1,*, Alexandr V. Bildyukevich 2 and Alexey V. Volkov 1 1 A.V. Topchiev Institute of Petrochemical Synthesis, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow 119991, Russia; [email protected] 2 Institute of Physical Organic Chemistry, National Academy of Sciences of Belarus, Minsk 220072, Belarus; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +7-495-647-5927 (ext. 202) Received: 14 September 2018; Accepted: 2 October 2018; Published: 10 October 2018 Abstract: Gas-liquid membrane contactors that were based on hollow fiber membranes are the example of highly effective hybrid separation processes in the field of membrane technology. Membranes provide a fixed and well-determined interface for gas/liquid mass transfer without dispensing one phase into another while their structure (hollow fiber) offers very large surface area per apparatus volume resulted in the compactness and modularity of separation equipment. In many cases, stated benefits are complemented with high separation selectivity typical for absorption technology. Since hollow fiber membrane contactors are agreed to be one of the most perspective methods for CO2 capture technologies, the major reviews are devoted to research activities within this field. This review is focused on the research works carried out so far on the applications of membrane contactors for other gas-liquid separation tasks, such as water deoxygenation/ozonation, air humidity control, ethylene/ethane separation, etc. A wide range of materials, membranes, and liquid solvents for membrane contactor processes are considered. Special attention is given to current studies on the capture of acid gases (H2S, SO2) from different mixtures. -

Effects of Anaesthesia Techniques and Drugs on Pulmonary Function

Review Article Effects of anaesthesia techniques and drugs on pulmonary function Address for correspondence: Vijay Saraswat Dr. Vijay Saraswat, Department of Anaesthesiology, Apollo Hospitals, Nashik, Maharashtra, India Apollo Hospitals, Nashik, Maharashtra, India. E‑mail: drvsaraswat@gmail. ABSTRACT com The primary task of the lungs is to maintain oxygenation of the blood and eliminate carbon dioxide through the network of capillaries alongside alveoli. This is maintained by utilising ventilatory reserve capacity and by changes in lung mechanics. Induction of anaesthesia impairs pulmonary functions by the loss of consciousness, depression of reflexes, changes in rib cage and haemodynamics. All drugs used during anaesthesia, including inhalational agents, affect pulmonary functions directly by acting on respiratory system or indirectly through their actions on other systems. Volatile anaesthetic agents have more pronounced effects on pulmonary functions compared to intravenous induction agents, leading to hypercarbia and hypoxia. The posture of the patient also leads to major changes in pulmonary functions. Anticholinergics and neuromuscular blocking agents have little effect. Analgesics and Access this article online sedatives in combination with volatile anaesthetics and induction agents may exacerbate Website: www.ijaweb.org their effects. Since multiple agents are used during anaesthesia, ultimate effect may be DOI: 10.4103/0019‑5049.165850 different from when used in isolation. Literature search was done using MeSH key words ‘anesthesia’, -

Respiratory System

Respiratory System 1 Respiratory System 2 Respiratory System 3 Respiratory System 4 Respiratory System 5 Respiratory System 6 Respiratory System 7 Respiratory System 8 Respiratory System 9 Respiratory System 10 Respiratory System 11 Respiratory System • Pulmonary Ventilation 12 Respiratory System 13 Respiratory System 14 Respiratory System • Measuring of Lung Function œ Compliance œ the ease at which the lungs and thoracic wall can be expanded œ if reduced it is more difficult to inflate the lungs œ causes: • Damaged lung tissue • Fluid within lung tissue • Decrease in pulmonary surfactant • Anything that impedes lung expansion or contraction œ Respiratory Volumes and Capacities will be covered in Lab œ 15 Respiratory System • Exchange of Oxygen and Carbon Dioxide œ Charles‘ Law œ the volume of a gas is directly proportional to the absolute temperature, assuming the pressure remains constant As gases enter the lung they warm and expand, increasing lung volume œ Dalton‘s Law œ each gas of a mixture of gases exerts its own pressure as if all the other gases were not present œ Henry‘s Law œ the quantity of a gas that will dissolve in a liquid is proportional to the partial pressure of the gas and its solubility coefficient, when the temperature remains constant 16 Respiratory System • External and Internal Respiration 17 Respiratory System • Transport of Oxygen and Carbon Dioxide by the Blood œ Oxygen Transport • 1.5% dissolved in plasma • 98.5% carried with Hbinside of RBC‘s as oxyhemoglobin œ Hbœ made up of protein portion called the globinportion -

The Respiratory System

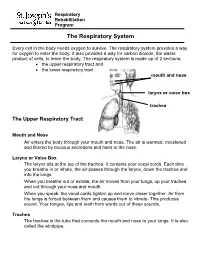

Respiratory Rehabilitation Program The Respiratory System Every cell in the body needs oxygen to survive. The respiratory system provides a way for oxygen to enter the body. It also provides a way for carbon dioxide, the waste product of cells, to leave the body. The respiratory system is made up of 2 sections: the upper respiratory tract and the lower respiratory tract mouth and nose larynx or voice box trachea The Upper Respiratory Tract Mouth and Nose Air enters the body through your mouth and nose. The air is warmed, moistened and filtered by mucous secretions and hairs in the nose. Larynx or Voice Box The larynx sits at the top of the trachea. It contains your vocal cords. Each time you breathe in or inhale, the air passes through the larynx, down the trachea and into the lungs. When you breathe out or exhale, the air moves from your lungs, up your trachea and out through your nose and mouth. When you speak, the vocal cords tighten up and move closer together. Air from the lungs is forced between them and causes them to vibrate. This produces sound. Your tongue, lips and teeth form words out of these sounds. Trachea The trachea is the tube that connects the mouth and nose to your lungs. It is also called the windpipe. The Lower Respiratory Tract Inside Lungs Outside Lungs bronchial tubes alveoli diaphragm (muscle) Bronchial Tubes The trachea splits into 2 bronchial tubes in your lungs. These are called the left bronchus and right bronchus. The bronchus tubes keep branching off into smaller and smaller tubes called bronchi. -

Gas Exchange in the Prone Posture

RESPIRATORY CARE Paper in Press. Published on May 30, 2017 as DOI: 10.4187/respcare.05512 Gas Exchange in the Prone Posture Nicholas J Johnson MD, Andrew M Luks MD, and Robb W Glenny MD Introduction Overview of Gas Exchange Lung Structure Normal Exchange of Oxygen and Carbon Dioxide Abnormal Exchange of Oxygen and Carbon Dioxide Gas Exchange in the Prone Posture Under Normal Conditions Spatial Distribution of Ventilation Spatial Distribution of Perfusion Ventilation and Perfusion Matching Mechanisms by Which the Prone Posture Improves Gas Exchange in Animal Models of ARDS Additional Physiologic Effects of the Prone Posture Clinical Trials Summary The prone posture is known to have numerous effects on gas exchange, both under normal condi- tions and in patients with ARDS. Clinical studies have consistently demonstrated improvements in oxygenation, and a multi-center randomized trial found that, when implemented within 48 h of moderate-to-severe ARDS, placing subjects in the prone posture decreased mortality. Improve- ments in gas exchange occur via several mechanisms: alterations in the distribution of alveolar ventilation, redistribution of blood flow, improved matching of local ventilation and perfusion, and reduction in regions of low ventilation/perfusion ratios. Ventilation heterogeneity is reduced in the prone posture due to more uniform alveolar size secondary to a more uniform vertical pleural pressure gradient. The prone posture results in more uniform pulmonary blood flow when com- pared with the supine posture, due to an anatomical bias for greater blood flow to dorsal lung regions. Because both ventilation and perfusion heterogeneity decrease in the prone posture, gas exchange improves. -

Gas Exchange and Gas Transfer

Gas exchange and gas transfer •Red: important •Black: in male / female slides •Pink: in female slides only Editing file •Blue: in male slides only •Yellow: notes •Gray: extra information Twitter account •Textbook: Guyton + Linda Objectives 1. Define partial pressure of a gas 2. Understand that the pressure exerted by each gas in a mixture of gases is independent of the pressure exerted by the other gases (Dalton's Law) 3. Understand that gases in a liquid diffuse from higher partial pressure to lower partial pressure (Henry’s Law) 4. Describe the factors that determine the concentration of a gas in a liquid. 5. Describe the components of the alveolar-capillary membrane (i.e., what does a molecule of gas pass through). 6. Knew the various factors determining gas transfer: - Surface area, thickness, partial pressure difference, and diffusion coefficient of gas 7. State the partial pressures of oxygen and carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, alveolar gas, at the end of the pulmonary capillary, in systemic capillaries, and at the beginning of a pulmonary capillary. Gas exchange through the respiratory membrane After the alveoli are ventilated with fresh air, the next step in the respiratory process is diffusion of oxygen from the alveoli into the pulmonary blood and diffusion of carbon dioxide in the opposite direction, out of the blood. Female’s slides only Composition of alveolar air and its relation to atmospheric air: The dry atmospheric air Alveolar air is partially O2 is constantly CO2 constantly diffuses enters the respiratory replaced by atmospheric absorbed from the from the pulmonary passage is humidified air with each breath.