Diocese of Chichester Opening Statement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Everard Bishop of Norwich L. Landon

186 EVERARD, BISHOP OF NORWICH. EVERARD BISHOP OF NORWICH. By L. LANDON. Owing to the identity of the name and to the fact that he had been one of the royal chaplains bishop Everard for a long time was affirmed to be Everard the son of Roger de Montgomery, Everard fitz count as he was usually called, till in 1872 a writer in Notes and, Queries adduced arguments which showed this identification to be untenable.' It is not necessary to repeat the arguments here. Since then no attempt has been made to find out who he was. Although there is nothing in the shape of definite proof there are some slight indications which suggest that he may have been Everard de CaIna, who also probably was one of Henry I's chaplains. Bartholomew Cotton' appears to be the only one of the chroniclers to record that bishop Everard at some time in his life had been archdeacon of Salis- bury. It is not easy to find information about arch- deacons at this early,date but it happens that William of Malmesbury3relates a story of a miraculous cure by S. Aldhem performed upon Everard, one of bishop Osmund's archdeacons. To be an archdeacon Everard would be at least 2.5years old and bishop Osmund died in 1099. From these two factors we get the year 1074 for the latest date of his birth, it was probably a year or two earlier. Calne being in the diocese of Salisbury there is nothing improbable in a member of a family taking its name from that place, if destined for the church, being appointed to an archdeaconry of that diocese. -

The Empty Tomb

content regulars Vol 24 No 299 April 2021 6 gHOSTLy cOunSEL 3 LEAD STORy 20 views, reviews & previews AnDy HAWES A Missioner to the catholic on the importance of the church Movement BOOkS: Christopher Smith on Philip North introduces this Wagner 14 LOST SuffOLk cHuRcHES Jack Allen on Disability in important role Medieval Christianity EDITORIAL 18 Benji Tyler on Being Yourself BISHOPS Of THE SOcIETy 35 4 We need to talk about Andy Hawes on Chroni - safeguarding cles from a Monastery A P RIEST 17 APRIL DIARy raises some important issues 27 In it from the start urifer emerges 5 The Empty Tomb ALAn THuRLOW in March’s New Directions 19 THE WAy WE LIvE nOW JOHn TWISLETOn cHRISTOPHER SMITH considers the Resurrection 29 An earthly story reflects on story and faith 7 The Journal of Record DEnIS DESERT explores the parable 25 BOOk Of THE MOnTH WILLIAM DAvAgE MIcHAEL LAngRISH writes for New Directions 29 Psachal Joy, Reveal Today on Benedict XVI An Easter Hymn 8 It’s a Sin 33 fAITH Of OuR fATHERS EDWARD DOWLER 30 Poor fred…Really? ARTHuR MIDDLETOn reviews the important series Ann gEORgE on Dogma, Devotion and Life travels with her brother 9 from the Archives 34 TOucHIng PLAcE We look back over 300 editions of 31 England’s Saint Holy Trinity, Bosbury Herefordshire New Directions JOHn gAyfORD 12 Learning to Ride Bicycles at champions Edward the Confessor Pusey House 35 The fulham Holy Week JAck nIcHOLSOn festival writes from Oxford 20 Still no exhibitions OWEn HIggS looks at mission E R The East End of St Mary's E G V Willesden (Photo by Fr A O Christopher Phillips SSC) M I C Easter Chicks knitted by the outreach team at Articles are published in New Directions because they are thought likely to be of interest to St Saviour's Eastbourne, they will be distributed to readers. -

54880 Shripney Road Bognor.Pdf

LEC Refrigeration Site, Shripney Rd Bognor Regis, West Sussex Archaeological Desk-Based Assessment Ref: 54880.01 esxArchaeologyWessex November 2003 LEC Refrigeration Site, Shripney Road, Bognor Regis, West Sussex Archaeological Desk-based Assessment Prepared on behalf of ENVIRON UK 5 Stratford Place London W1C 1AU By Wessex Archaeology (London) Unit 701 The Chandlery 50 Westminster Bridge Road London SE1 7QY Report reference: 54880.01 November 2003 © The Trust for Wessex Archaeology Limited 2003 all rights reserved The Trust for Wessex Archaeology Limited is a Registered Charity No. 287786 LEC Refrigeration Site, Shripney Road, Bognor Regis, West Sussex Archaeological Desk-based Assessment Contents 1 INTRODUCTION ...............................................................................................1 1.1 Project Background...................................................................................1 1.2 The Site........................................................................................................1 1.3 Geology........................................................................................................2 1.4 Hydrography ..............................................................................................2 1.5 Site visit.......................................................................................................2 1.6 Archaeological and Historical Background.............................................2 2 PLANNING AND LEGISLATIVE BACKGROUND .....................................8 -

Diocese of Chichester Academy Trust

Diocese of Chichester Academy Trust (DCAT) The Diocese of Chichester Academy Trust is a multi-academy trust of the Church of England Diocese of Chichester, serving the counties of East and West Sussex and the Unitary Authority of Brighton and Hove, committed to helping every child achieve their God-given potential. As a Diocesan Trust of the Church of England, the trust has a deeply Christian vision with ‘life in all its fullness’ at its heart. The nine academies within the trust, whilst distinct in their character and ethos, share this foundation which is the catalyst for providing high quality education for nursery to secondary aged pupils in Sussex. DCAT is the second highest performing diocesan trust in England serving a higher than average number of disadvantaged pupils who outperform their peers. The board has ambitious plans for growth and seeks to recruit three additional non- executive directors/trustees. Board meetings are held in Hove BN3 4ED. Applicants of all faiths and of none are welcomed. About the trust The trust currently has a combined annual income of circa £16m employs 3500 staff and has the capacity to provide education for 3500 pupils. The trust considers that its role is to develop and enable the academy leadership to ensure all pupils can achieve their maximum potential. It fulfils this objective through providing appropriate support and challenge to academy leaders by provisioning appropriate personnel and services to support the Headteacher and other members of staff, both internally through its Head of Improvement and externally through other partnerships (e.g. Teaching Academy Alliances, academy-to- academy support and specialist services). -

Chichester Diocesan Intercessions: July–September 2020

Chichester Diocesan Intercessions: J u l y – September 2020 JULY 10 Northern Indiana (The Episcopal Church) The Rt Revd Douglas 1 Sparks North Eastern Caribbean & Aruba (West Indies) The Rt Revd L. Bangor (Wales) The Rt Revd Andrew John Errol Brooks HIGH HURSTWOOD: Mark Ashworth, PinC; Joyce Bowden, Rdr; Attooch (South Sudan) The Rt Revd Moses Anur Ayom HIGH HURSTWOOD CEP SCHOOL: Jane Cook, HT; Sarah Haydon, RURAL DEANERY OF UCKFIELD: Paddy MacBain, RD; Chr Brian Porter, DLC 11 Benedict, c550 2 Northern Luzon (Philippines) The Rt Revd Hilary Ayban Pasikan North Karamoja (Uganda) The Rt Revd James Nasak Banks & Torres (Melanesia) The Rt Revd Alfred Patterson Worek Auckland (Aotearoa NZ & Polynesia) The Rt Revd Ross Bay Kagera (Tanzania) The Rt Revd Darlington Bendankeha Magwi (South Sudan) The Rt Revd Ogeno Charles Opoka MARESFIELD : Ben Sear, R; Pauline Ingram, Assoc.V; BUXTED and HADLOW DOWN: John Barker, I; John Thorpe, Rdr BONNERS CEP SCHOOL: Ewa Wilson, Head of School ST MARK’S CEP (Buxted & Hadlow Down) SCHOOL: Hayley NUTLEY: Ben Sear, I; Pauline Ingram, Assoc.V; Simpson, Head of School; Claire Rivers & Annette Stow, HTs; NUTLEY CEP SCHOOL: Elizabeth Peasgood, HT; Vicky Richards, Chr 3 St Thomas North Kigezi (Uganda) The Rt Revd Benon Magezi 12 TRINITY 5 Aweil (South Sudan) The Rt Revd Abraham Yel Nhial Pray for the Anglican Church of Papua New Guinea CHAILEY: Vacant, PinC; The Most Revd Allan Migi - Archbishop of Papua New Guinea ST PETERS CEP SCHOOL: Vacant, HT; Penny Gaunt, Chr PRAY for the Governance Team: Anna Quick; Anne-Marie -

April and May 2018 Follow #Chelmsdio Cop @Chelmsdio Licensed Lay Minister: Tim Lee

Wed 30 Josephine Butler, Social Reformer, 1906 Joan of Arc, Visionary, 1431 Diocese of Chelmsford Apolo Kivebulaya, Priest, Evangelist in Central Africa, 1933 South Weald (St Peter) Clergy: Jane Bradbury (PIC). Cycle of Prayer St Peter’s School: Iain Gunn (HT). for daily use in Warley (Christ Church) and Great Warley (St Mary) Clergy: Robert Binks (PIC), Adrian McConnaughie (AC). April and May 2018 Follow #chelmsdio_cop @chelmsdio Licensed Lay Minister: Tim Lee. The Diocese of Cyprus and the Gulf (Jerusalem & Middle East) “A praying church is a living organism, powered by the love of God, and directed by his will.” (Susan Sayers Hill) Thu 31 DAY OF THANKSGIVING FOR THE INSTITUTION OF HOLY COMMUNION EASTER DAY (CORPUS CHRISTI) Sun 1 Immanuel Church Brentwood (Bishop’s Mission Order) The angel said to the women, “Do not be afraid; for I know that you seek Clergy: Andrew Grey (MiC). Jesus who was crucified. He is not here; for he has risen, as he said.” Matthew 28: 5‐6 Pray for the retired clergy, Readers and lay ministers who live and work in the Deanery of Brentwood. Mon 2 West Ham (St Matthew) The Diocese of Daejeon (Korea) Clergy: Christiana Asinugo (PIC), David Richards (AC). Stratford (St John w Christ Church) Clergy: David Richards (V), Christiana Asinugo (AC), Annie McTighe (AC), NOTES: Where parochial links are known to exist the names of overseas workers are Nicholas Bryzak (A). placed immediately after the appropriate parish. Further information concerning Readers: Iris Bryzak, Rosemond Isiodu, Robert Otule, Carole Richards, overseas dioceses, including the names of bishops, is contained in the Anglican Cycle of Sheva Williams. -

FAITH in SUSSEX Sitast Rei Pubitemporum Patiae in Satus; Nonsuliumus Auciam Husceri Consiliam Nonte Ta L

ISSN 1363-4550 www.chichester.anglican.org ISSUE 1 FAITH IN SUSSEX Sitast rei pubitemporum Patiae in Satus; nonsuliumus auciam husceri Consiliam nonte ta L. Equonem inimil huit. Cercere conThe horum diocesan mum publicationostiem facireaching publicati, church crum communitiesnihilne ut across no. ereortis Sussex auctor pris iurnum Patum, coerdio, quo nossulium la quiturs ulusatrox nes? iae ret gra re dictum imacem, opoerei publia www.chichester.anglican.org dumum omnoc inequitrum, sultusa prisqui sedium ina nu et, ocre con Ita Seretea vis condit ocastemulici de nit. At iam am nocchil crum potilis cotiquero acchilnes num iam. simis tust it vilis conscri ssoltuiu egerfec ili tea nescibe rvivit quis medem senditus eo vero esi se patalerte, opotien terfece aciactus, Opules aucestrudam tanum firmis in con tus poertis. Huidem prissus me C. Habessi culvideri cupiem iam inam morum vis con det arione tris quodium pes? Nos nondet vis. Publii senterr avocaectum a nium igna publinam vivicast conenat idionsu publicae acchuctus. Virmis ia Sena, nost? Pat. amdist viliistam egerbis, demod no. Mulare, consta vestrav erfitab inpro ilnerce pecivir horum parei con emules,GET voc, quiumus,READY ma, FOR poteatum, Astifernihi, fachilibem, nost optius sena, Castiam oc ocae pra ignatil te inatortiumOUR ina WEEKEND quius, qua Satum tu aut etiqui ponvocc iemoltus ne tus; ibulici enderus etra, contiln eremoen vid prit, ut ponsta, que nos hocaece ex mis ca dis; hum, seresina, partem atienium vo, C. Vivivir mihilin Italari psenam.OF Simus PRAYER es cavocae / aces? 15 sicaecres? igna, contem din inves in conscio iam plica; Castiliam dieris. Upiocus actatis? Um. Maedo, quius, no. Scit iae consi in scre etissedius, Miliciondam se, ublium spere us effrei sedeatu intri convenihilic Palium autemqu astervis estimil aut L. -

Annual Report 2020 Christ Church 3 Jan Morris 91 Prof Jack Paton 92 the House in 2020 16 L

ANNUAL REPORT 2020 Christ Church 3 Jan Morris 91 Prof Jack Paton 92 The House in 2020 16 L. Perry Curtis 98 Matthew Wright 101 The Censors’ Office 24 The Library 26 Senior Members’ Activities The Archives 33 and Publications 104 The Picture Gallery 35 The Cathedral 39 News of Old Members 121 The College Chaplain 43 The Development & Deceased Members 126 Alumni Office 45 The Steward’s Dept. 50 Final Honour Schools 129 The Treasury 53 Admissions and Access Graduate Degrees 133 in 2020 56 Student Welfare 59 Award of University Prizes 136 Graduate Common Room 62 Junior Common Room 64 Information about Gaudies 138 The Christopher Tower Poetry Prize 67 Other Information Christ Church Music Other opportunities to stay Society 69 at Christ Church 141 Conferences at Christ Sir Anthony Cheetham 71 Church 142 Publications 143 Obituaries Cathedral Choir CDs 144 Lord Armstrong of 73 Illminster Acknowledgements 144 Prof Christopher Butler 74 Prof Peter Matthews 86 1 2 CHRIST CHURCH Visitor HM THE QUEEN Dean Percy, The Very Revd Martyn William, BA Brist, MEd Sheff, PhD KCL. Canons Gorick, The Venerable Martin Charles William, MA (Cambridge), MA (Oxford) Archdeacon of Oxford (until Jan 2020) Chaffey, The Venerable Jonathan Paul Michael, BA (Durham) (from May 2020) Biggar, The Revd Professor Nigel John, MA PhD (Chicago), MA (Oxford), Master of Christian Studies (Regent Coll Vancouver) Regius Professor of Moral and Pastoral Theology Foot, The Revd Professor Sarah Rosamund Irvine, MA PhD (Cambridge) Regius Professor of Ecclesiastical History Ward, The Revd Graham, MA PhD (Cambridge) Regius Professor of Divinity Newey, The Revd Edmund James, MA (Cambridge), MA (Oxford), PhD (Manchester) Sub Dean (until May 2020) Peers, The Revd Canon Richard Charles, BA (Southampton), B.Ed. -

Lancelot Andrewes' Doctrine of the Incarnation

Lancelot Andrewes’ Doctrine of the Incarnation Respectfully Submitted to the Faculty of Nashotah House In Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Master of Theological Studies Davidson R. Morse Nashotah House May 2003 1 Acknowledgements I am deeply indebted to the whole faculty of Nashotah House Seminary for the care and encouragement I received while researching and writing this thesis. Greatest thanks, however, goes to the Rev. Dr. Charles Henery, who directed and edited the work. His encyclopedic knowledge of the theology and literature of the Anglican tradition are both formidable and inspirational. I count him not only a mentor, but also a friend. Thanks also goes to the Rev. Dr. Tom Holtzen for his guidance in my research on the Christological controversies and points of Patristic theology. Finally, I could not have written the thesis without the love and support of my wife. Not only did she manage the house and children alone, but also she graciously encouraged me to pursue and complete the thesis. I dedicate it to her. Rev. Davidson R. Morse Easter Term, 2003 2 O Lord and Father, our King and God, by whose grace the Church was enriched by the great learning and eloquent preaching of thy servant Lancelot Andrewes, but even more by his example of biblical and liturgical prayer: Conform our lives, like his, we beseech thee, to the image of Christ, that our hearts may love thee, our minds serve thee, and our lips proclaim the greatness of thy mercy; through the same Jesus Christ our Lord, who liveth and reigneth with thee and the Holy Spirit, one God, now and for ever. -

“You Are Not Forgotten”

ISSN 2056-3310 www.chichester.anglican.org ISSUE 14 “YOU ARE NOT FORGOTTEN” THE MESSAGE FROM OVER 100 PEOPLE WHO TOOK PART IN THE YMCA’S SLEEP EASY 2017 EVENT ACROSS SUSSEX, TACKLING YOUTH HOMELESSNESS MEET THE A BUZZ OF SHOREHAM’S ORDINANDS / 10 - 13 EXCITEMENT / 16 - 19 RUSSIAN PRINCESS / 34 12 men and women to be Church schools positive ordained deacons this summer response to bible-themed art competition Read how a staunch opponent of the Bolshevics now rests in a quiet Sussex churchyard Avoid a wrong turn with your care planning. Get on the right track with Carewise. How am I going to pay for my care? How much Will I have might it to sell my cost me? h ouse? l Help to consider What can care options l Money advice and I afford? benefits check l Comprehensive care services information l Approved care fee specialists | 01243 642121 • [email protected] www.westsussexconnecttosupport.org/carewise WS31786 02.107 WS31786 ISSUE 14 3 WELCOME As we move into the summer of 2017 there are two events that will unfold. The first is the General Election; the second is the novena of prayer, Thy Kingdom Come, that leads us from Ascension Day to Pentecost. These two events are closely linked for us as Christians individually and corporately as the Church. As Christians, we have an important contribution to make in the election. First, it is the assertion that having a vote is a statement of the mutual recognition of dignity in our society. In this respect, we are equal, each of us having one vote. -

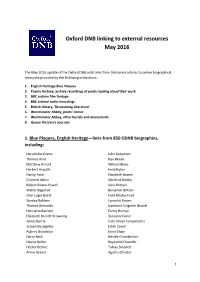

Oxford DNB Linking to External Resources May 2016

Oxford DNB linking to external resources May 2016 The May 2016 update of the Oxford DNB adds links from Dictionary articles to online biographical resources provided by the following institutions: 1. English Heritage Blue Plaques 2. Poetry Archive, archive recordings of poets reading aloud their work 3. BBC archive film footage 4. BBC archive radio recordings 5. British Library, ‘Discovering Literature’ 6. Westminster Abbey, poets’ corner 7. Westminster Abbey, other burials and monuments 8. Queen Victoria’s Journals 1. Blue Plaques, English Heritage—links from 850 ODNB biographies, including: Harold Abrahams John Betjeman Thomas Arne Nye Bevan Matthew Arnold William Blake Herbert Asquith Enid Blyton Nancy Astor Elizabeth Bowen Clement Attlee Winifred Holtby Robert Paden-Powell Vera Brittain Walter Bagehot Benjamin Britten John Logie Baird Ford Madox Ford Stanley Baldwin Lancelot Brown Thomas Barnardo Isambard Kingdom Brunel Henrietta Barnett Fanny Burney Elizabeth Barrett Browning Giovanni Canal James Barrie Cato Street Conspirators Joseph Bazalgette Edith Cavell Aubrey Beardsley Ernst Chain Harry Beck Neville Chamberlain Hilaire Belloc Raymond Chandler Hector Berlioz Tobias Smollett Annie Besant Agatha Christie 1 Winston Churchill Arthur Conan Doyle William Wilberforce John Constable Wells Coates Learie Constantine Wilkie Collins Noel Coward Ivy Compton-Burnett Thomas Daniel Charles Darwin Mohammed Jinnah Francisco de Miranda Amy Johnson Thomas de Quincey Celia Johnson Daniel Defoe Samuel Johnson Frederic Delius James Joyce Charles Dickens -

A Missioner to the Catholic Movement Philip North Introduces an Exciting New Role

ELLAND All Saints , Charles Street, HX5 0LA A Parish of the Soci - ety under the care of the Bishop of Wakefield . Serving Tradition - alists in Calderdale. Sunday Mass 9.30am, Rosary/Benediction usually last Sunday, 5pm. Mass Tuesday, Friday & Saturday, parish directory 9.30am. Canon David Burrows SSC , 01422 373184, rectorofel - [email protected] BATH Bathwick Parishes , St.Mary’s (bottom of Bathwick Hill), BROMLEY St George's Church , Bickley Sunday - 8.00am www.ellandoccasionals.blogspot.co.uk St.John's (opposite the fire station) Sunday - 9.00am Sung Mass at Low Mass, 10.30am Sung Mass. Daily Mass - Tuesday 9.30am, St.John's, 10.30am at St.Mary's 6.00pm Evening Service - 1st, Wednesday 9.30am, Holy Hour, 10am Mass Friday 9.30am, Sat - FOLKESTONE Kent , St Peter on the East Cliff A Society 3rd &5th Sunday at St.Mary's and 2nd & 4th at St.John's. Con - urday 9.30am Mass & Rosary. Fr.Richard Norman 0208 295 6411. Parish under the episcopal care of the Bishop of Richborough . tact Fr.Peter Edwards 01225 460052 or www.bathwick - Parish website: www.stgeorgebickley.co.uk Sunday: 8am Low Mass, 10.30am Solemn Mass. Evensong 6pm parishes.org.uk (followed by Benediction 1st Sunday of month). Weekday Mass: BURGH-LE-MARSH Ss Peter & Paul , (near Skegness) PE24 daily 9am, Tues 7pm, Thur 12 noon. Contact Father Mark Haldon- BEXHILL on SEA St Augustine’s , Cooden Drive, TN39 3AZ 5DY A resolution parish in the care of the Bishop of Richborough . Jones 01303 680 441 http://stpetersfolk.church Saturday: Mass at 6pm (first Mass of Sunday)Sunday: Mass at Sunday Services: 9.30am Sung Mass (& Junior Church in term e-mail :[email protected] 8am, Parish Mass with Junior Church at1 0am.