NEWS and NOTES by Paul Hess

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

6-A John James Audubon, American Flamingo, 1838

JOHN JAMES AUDUBON [1785–1851] 6 a American Flamingo,1838 American Flamingo is one of the 435 hand-colored engravings that River, a major flyway for migratory birds, and eventually wan- make up John James Audubon’s monumental Birds of America, dered farther from home to comb the American frontier for issued in four volumes between 1826 and 1838. The massive unrecorded species. publication includes life-size representations of nearly five hundred Audubon’s procedure was to study and sketch a bird in its natural species of North American birds. Although Audubon was not the habitat before killing it carefully, using fine shot to minimize dam- first to attempt such a comprehensive catalog, his work departed age. His critical innovation was to then thread wire through the from conventional scientific illustration, which showed lifeless spec- specimen, allowing him to fashion a lifelike pose. He worked in imens against a blank background, by presenting the birds as they watercolor, and had completed some four hundred paintings appeared in the wild. When his pictures were first published, when he decided to publish them as a folio of prints. Failing to find some naturalists objected to Audubon’s use of dramatic action and support in Philadelphia, he sailed for England, where he became pictorial design, but these are the qualities that set his work apart lionized as “The American Woodsman.” The engraving firm and make it not only an invaluable record of early American Robert Havell and Son took on the challenge of reproducing wildlife but an unmatched work of American art. Audubon’s paintings on copper plates and tinting the resulting John James Audubon was born in Haiti and educated in France, black-and-white prints by hand. -

A Pliocene Flamingo from Mexico

June, 1944 THE WILSON BULLETIN 77 Vol. 56. No. 2 A PLIOCENE FLAMINGO FROM MEXICO BY LOYE MILLER IELD parties from the California Institute of Technology have been F fortunate in locating a variety of fossil deposits in Mexico that in- cluded bird remains. Some have been very rich in the quantity and variety of material; for example, the San Josecito Cavern of Nuevo Leon (Miller, ,1943), a deposit of Pleistocene age, yielded several thousand bird bones assigned to over forty species. The present paper deals with a collection of ten fragments, all but one of which are in- cluded in a single species. I am indebted to Dr. Chester Stock in charge of the explorations for the opportunity of working with the bird collec- tions. Dr. Alexander Wetmore has loaned comparative material, and Dr. Hildegarde Howard has been a most congenial fellow student during many conferences on the flamingoes, both Recent and Fossil. To these several colleagues my sincere thanks are offered. The ten fragments are from collecting locality No. 289, California Institute of Technology, known. as the Rincon Pliocene, Chihuahua, Mexico. Associated mammal remains include horse, camel, antelope, and carnivore species. The matrix is a fine grained silt of lightest color, without cementing material. A stiff brush serves to remove it from the well petrified bones. Unfortunately the specimens are most frag- mentary. They do, however, prove to be of interest in several respects; most notably they prove (since several speciments are from pre-volant young) that a small speciesof flamingo was present as a breeding bird. This is the earliest record for the family in America. -

Flamingo ABOUT the GROUP

Flamingo ABOUT THE GROUP Bulletin of the IUCN-SSC/Wetlands International The Flamingo Specialist Group (FSG) was established in 1978 at Tour du Valat in France, under the leadership of Dr. Alan Johnson, who coordinated the group until 2004 (see profile at www.wetlands.org/networks/Profiles/January.htm). Currently, the group is FLAMINGO SPECIALIST GROUP coordinated from the Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust at Slimbridge, UK, as part of the IUCN- SSC/Wetlands International Waterbird Network. The FSG is a global network of flamingo specialists (both scientists and non- scientists) concerned with the study, monitoring, management and conservation of the world’s six flamingo species populations. Its role is to actively promote flamingo research and conservation worldwide by encouraging information exchange and cooperation amongst these specialists, and with other relevant organisations, particularly IUCN - SSC, Ramsar, WWF International and BirdLife International. FSG members include experts in both in-situ (wild) and ex-situ (captive) flamingo conservation, as well as in fields ranging from field surveys to breeding biology, diseases, tracking movements and data management. There are currently 165 members around the world, from India to Chile, and from France to South Africa. Further information about the FSG, its membership, the membership list serve, or this bulletin can be obtained from Brooks Childress at the address below. Chair Assistant Chair Dr. Brooks Childress Mr. Nigel Jarrett Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust Slimbridge Slimbridge Glos. GL2 7BT, UK Glos. GL2 7BT, UK Tel: +44 (0)1453 860437 Tel: +44 (0)1453 891177 Fax: +44 (0)1453 860437 Fax: +44 (0)1453 890827 [email protected] [email protected] Eastern Hemisphere Chair Western Hemisphere Chair Dr. -

GREATER and LESSER FLAMINGOS Phoenicopterus Ruber and Phoeniconaias Minor

GREATER AND LESSER FLAMINGOS Phoenicopterus ruber and Phoeniconaias minor Greater and Lesser Flamingos © Cliff Buckton © P & H Harris Lesser Flamingo The Lesser Flamingo Phoeniconaias minor is the smallest of the world's five flamingo species. It occurs primarily in the Rift Valley lakes of East Africa with about 4 to 5 million birds estimated, but also in small populations in Namibia/Botswana (40,000), Mauritania/Senegal (15,400), Ethiopia (8,300). The alkaline lakes of the Rift Valley are the primary feeding areas for the East Africa population. During non-breeding periods these lakes often hold almost the entire population. Huge feeding flocks of 1-2 million birds frequently gather on lakes Bogoria and Nakuru, creating one of the most stunning wildlife spectacles in the world. Although it is still the most numerous of the five species, the Lesser Flamingo is classified as globally "near threatened" due primarily to its dependence on a limited number of unprotected breeding sites and threats of proposed soda-ash mining and hydro-electric power schemes on the main breeding lakes. The question of whether there is occasional interchange between the East African and southern African populations has yet to be resolved definitely, but considerable circumstantial evidence has now been assembled to show that East African Lesser Flamingos probably do fly to Botswana to breed during periods when the Lake Makgadikgadi Salt Pans are flooded. Their migration routes, flight range and stopover places (if any) are still unknown. It is now known that Lesser Flamingos do fly during the day, at great heights, well above the normal diurnal movement of eagles, their main aerial predator. -

Flamingo Newsletter 17, 2009

ABOUT THE GROUP The Flamingo Specialist Group (FSG) is a global network of flamingo specialists (both scientists and non-scientists) concerned with the study, monitoring, management and conservation of the world’s six flamingo species populations. Its role is to actively promote flamingo research, conservation and education worldwide by encouraging information exchange and cooperation among these specialists, and with other relevant organisations, particularly the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC), the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands, the Convention on Conservation of Migratory Species (CMS), the African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbird Agreement (AEWA), and BirdLife International. The group is coordinated from the Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust, Slimbridge, UK, as part of the IUCN-SSC/Wetlands International Waterbird Network. FSG members include experts in both in-situ (wild) and ex-situ (captive) flamingo conservation, as well as in fields ranging from research surveys to breeding biology, infectious diseases, toxicology, movement tracking and data management. There are currently 286 members representing 206 organisations around the world, from India to Chile, and from France to South Africa. Further information about the FSG, its membership, the membership list serve, or this bulletin can be obtained from Brooks Childress at the address below. Chair Dr. Brooks Childress Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust Slimbridge Glos. GL2 7BT, UK Tel: +44 (0)1453 860437 Fax: +44 (0)1453 860437 [email protected] Eastern Hemisphere Chair Western Hemisphere Chair Dr. Arnaud Béchet Dr. Felicity Arengo Station biologique, Tour du Valat American Museum of Natural History Le Sambuc Central Park West at 79th Street 13200 Arles, France New York, NY 10024 USA Tel : +33 (0) 4 90 97 20 13 Tel: +1 212 313-7076 Fax : +33 (0) 4 90 97 20 19 Fax: +1 212 769-5292 [email protected] [email protected] Citation: Childress, B., Arengo, F. -

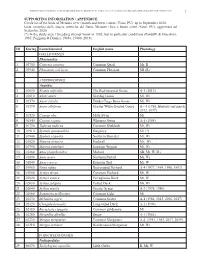

1 ID Euring Latin Binomial English Name Phenology Galliformes

BIRDS OF METAURO RIVER: A GREAT ORNITHOLOGICAL DIVERSITY IN A SMALL ITALIAN URBANIZING BIOTOPE, REQUIRING GREATER PROTECTION 1 SUPPORTING INFORMATION / APPENDICE Check list of the birds of Metauro river (mouth and lower course / Fano, PU), up to September 2020. Lista completa delle specie ornitiche del fiume Metauro (foce e basso corso /Fano, PU), aggiornata ad Settembre 2020. (*) In the study area 1 breeding attempt know in 1985, but in particolar conditions (Pandolfi & Giacchini, 1985; Poggiani & Dionisi, 1988a, 1988b, 2019). ID Euring Latin binomial English name Phenology GALLIFORMES Phasianidae 1 03700 Coturnix coturnix Common Quail Mr, B 2 03940 Phasianus colchicus Common Pheasant SB (R) ANSERIFORMES Anatidae 3 01690 Branta ruficollis The Red-breasted Goose A-1 (2012) 4 01610 Anser anser Greylag Goose Mi, Wi 5 01570 Anser fabalis Tundra/Taiga Bean Goose Mi, Wi 6 01590 Anser albifrons Greater White-fronted Goose A – 4 (1986, february and march 2012, 2017) 7 01520 Cygnus olor Mute Swan Mi 8 01540 Cygnus cygnus Whooper Swan A-1 (1984) 9 01730 Tadorna tadorna Common Shelduck Mr, Wi 10 01910 Spatula querquedula Garganey Mr (*) 11 01940 Spatula clypeata Northern Shoveler Mr, Wi 12 01820 Mareca strepera Gadwall Mr, Wi 13 01790 Mareca penelope Eurasian Wigeon Mr, Wi 14 01860 Anas platyrhynchos Mallard SB, Mr, W (R) 15 01890 Anas acuta Northern Pintail Mi, Wi 16 01840 Anas crecca Eurasian Teal Mr, W 17 01960 Netta rufina Red-crested Pochard A-4 (1977, 1994, 1996, 1997) 18 01980 Aythya ferina Common Pochard Mr, W 19 02020 Aythya nyroca Ferruginous -

The Handrearing of a Chilian Flamingo And

£; 'E (j) CJ) :§ o > .0 o (5 .c 0.. PInk Floyd The Handrearing ofa Chilian Flamingo and its Introduction to the Flock Floyd (second from right) seen as a member ofthe flock. He can be distinguished be the light by Chris Smith gray down on the headand neckand by the lighter shade ofpink on the body andwings. Shortly Animal Technician after Floyd was introduced to the flock, several pairs C!f.flamingos successfully hatched and Oklahoma City Zoological Park reared theiryoung. ink Floyd: to many people it is birds care. However, after one of the hatching, chicks stay in or near the the name of a rock band that has first eggs disappeared from the nest, nest for about the first week. After Precorded many cIa sic albums the remaining and subsequent eggs leaving the nest, chicks congregate such as "The Wall" and "The Dark Side were pulled and replaced with dummy with other chicks, forming creches or of the Moon. ' To the personnel at the eggs. The eggs were placed in incuba nursery groups. These creches can Oklahoma City Zoological Park, it is also tor at a temperature of 99.5° F. (37.5° consist of several thousand young the name of its first captive-hatched C). The hygrometer was maintained birds. Chilean Flamingo, Phoenicopterus between 82-84°F (30-31°C). The eggs Adult flamingos take turns watching chilensis. were turned five times daily. A total of over the chicks. While the chicks are in The Oklahoma City Zoo has exhib eight flamingo eggs were pulled from the nursery, the parents continue to ited Chilean Flamingos since 1966, but the nests. -

Modern Birds Classification System Tinamiformes

6.1.2011 Classification system • Subclass: Neornites (modern birds) – Superorder: Paleognathae, Neognathae Modern Birds • Paleognathae – two orders, 49 species • Struthioniformes—ostriches, emus, kiwis, and allies • Tinamiformes—tinamous Ing. Jakub Hlava Department of Zoology and Fisheries CULS Tinamiformes • flightless • Dwarf Tinamou • consists of about 47 species in 9 genera • Dwarf Tinamou ‐ 43 g (1.5 oz) and 20 cm (7.9 in) • Gray Tinamou ‐ 2.3 kg (5.1 lb) 53 cm (21 in) • small fruits and seeds, leaves, larvae, worms, and mollusks • Gray Tinamou 1 6.1.2011 Struthioniformes Struthioniformes • large, flightless birds • Ostrich • most of them now extinct • Cassowary • chicks • Emu • adults more omnivorous or insectivorous • • adults are primarily vegetarian (digestive tracts) Kiwi • Emus have a more omnivorous diet, including insects and other small animals • kiwis eat earthworms, insects, and other similar creatures Neognathae Galloanserae • comprises 27 orders • Anseriformes ‐ waterfowl (150) • 10,000 species • Galliformes ‐ wildfowl/landfowl (250+) • Superorder Galloanserae (fowl) • Superorder Neoaves (higher neognaths) 2 6.1.2011 Anseriformes (screamers) Anatidae (dablling ducks) • includes ducks, geese and swans • South America • cosmopolitan distribution • Small group • domestication • Large, bulky • hunted animals‐ food and recreation • Small head, large feet • biggest genus (40‐50sp.) ‐ Anas Anas shoveler • mallards (wild ducks) • pintails • shlhovelers • wigeons • teals northern pintail wigeon male (Eurasian) 3 6.1.2011 Tadorninae‐ -

AOU Classification Committee – North and Middle America

AOU Classification Committee – North and Middle America Proposal Set 2016-C No. Page Title 01 02 Change the English name of Alauda arvensis to Eurasian Skylark 02 06 Recognize Lilian’s Meadowlark Sturnella lilianae as a separate species from S. magna 03 20 Change the English name of Euplectes franciscanus to Northern Red Bishop 04 25 Transfer Sandhill Crane Grus canadensis to Antigone 05 29 Add Rufous-necked Wood-Rail Aramides axillaris to the U.S. list 06 31 Revise our higher-level linear sequence as follows: (a) Move Strigiformes to precede Trogoniformes; (b) Move Accipitriformes to precede Strigiformes; (c) Move Gaviiformes to precede Procellariiformes; (d) Move Eurypygiformes and Phaethontiformes to precede Gaviiformes; (e) Reverse the linear sequence of Podicipediformes and Phoenicopteriformes; (f) Move Pterocliformes and Columbiformes to follow Podicipediformes; (g) Move Cuculiformes, Caprimulgiformes, and Apodiformes to follow Columbiformes; and (h) Move Charadriiformes and Gruiformes to precede Eurypygiformes 07 45 Transfer Neocrex to Mustelirallus 08 48 (a) Split Ardenna from Puffinus, and (b) Revise the linear sequence of species of Ardenna 09 51 Separate Cathartiformes from Accipitriformes 10 58 Recognize Colibri cyanotus as a separate species from C. thalassinus 11 61 Change the English name “Brush-Finch” to “Brushfinch” 12 62 Change the English name of Ramphastos ambiguus 13 63 Split Plain Wren Cantorchilus modestus into three species 14 71 Recognize the genus Cercomacroides (Thamnophilidae) 15 74 Split Oceanodroma cheimomnestes and O. socorroensis from Leach’s Storm- Petrel O. leucorhoa 2016-C-1 N&MA Classification Committee p. 453 Change the English name of Alauda arvensis to Eurasian Skylark There are a dizzying number of larks (Alaudidae) worldwide and a first-time visitor to Africa or Mongolia might confront 10 or more species across several genera. -

Ward-Nutrient Composition of American Flamingo Crop Milk.Pdf

Nutrient Composition Of American Flamingo Crop Milk Ann M. Ward1, Amy Hunt1, Mike Maslanka1*, and Chris Brown2 1 Nutritional Services Department, Fort Worth Zoo, Fort Worth, Texas USA 2Bird Department, Dallas Zoo, Dallas, Texas USA Crop milk samples (30 mL) were collected from juvenile (6-7 wks old) American flamingos (Phoenicopterus ruber ruber, n = 14) in the Ria Lagartos Biosphere Reserve (El Cuyo, Mexico) on the northern coast of the Yucatan Peninsula. The samples were analyzed for dry matter, crude protein, fat, minerals (calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, manganese, sodium, potassium, iron, copper, manganese, molybdenum, zinc), vitamin A, vitamin E, lutein and zeaxanthin, beta-cryptoxanthin, echinenone, canthaxanthin, and beta-carotene. In addition, morphometric measurements and blood samples were taken at the time of sample collection. This information will allow us to learn more about crop milk and avian lactation, and, most practically, to aid in flamingo hand-rearing efforts. Key words: Phoenicopterus ruber ruber, carotenoids, holocrine secretion INTRODUCTION American flamingos (Phoenicopterus ruber ruber) occur throughout the coastal wetland system of the Yucatan Peninsula. One of the largest flamingo colonies nests in the Ria Lagartos Lagoon on the northeastern coast. These birds utilize the surrounding habitat, which includes local commercial salt production operations, for roosting and foraging throughout the year [Arengo and Baldassarre, 1998]. Flamingos support their young for up to six months with crop milk. Along with several species of pigeons and doves, and some penguins, flamingos share with mammals the ability to secrete milk for the nourishment of their young. Much like in mammals, the production of milk in birds is prolactin mediated. -

Federal Register/Vol. 85, No. 74/Thursday, April 16, 2020/Notices

21262 Federal Register / Vol. 85, No. 74 / Thursday, April 16, 2020 / Notices acquisition were not included in the 5275 Leesburg Pike, Falls Church, VA Comment (1): We received one calculation for TDC, the TDC limit would not 22041–3803; (703) 358–2376. comment from the Western Energy have exceeded amongst other items. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: Alliance, which requested that we Contact: Robert E. Mulderig, Deputy include European starling (Sturnus Assistant Secretary, Office of Public Housing What is the purpose of this notice? vulgaris) and house sparrow (Passer Investments, Office of Public and Indian Housing, Department of Housing and Urban The purpose of this notice is to domesticus) on the list of bird species Development, 451 Seventh Street SW, Room provide the public an updated list of not protected by the MBTA. 4130, Washington, DC 20410, telephone (202) ‘‘all nonnative, human-introduced bird Response: The draft list of nonnative, 402–4780. species to which the Migratory Bird human-introduced species was [FR Doc. 2020–08052 Filed 4–15–20; 8:45 am]‘ Treaty Act (16 U.S.C. 703 et seq.) does restricted to species belonging to biological families of migratory birds BILLING CODE 4210–67–P not apply,’’ as described in the MBTRA of 2004 (Division E, Title I, Sec. 143 of covered under any of the migratory bird the Consolidated Appropriations Act, treaties with Great Britain (for Canada), Mexico, Russia, or Japan. We excluded DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR 2005; Pub. L. 108–447). The MBTRA states that ‘‘[a]s necessary, the Secretary species not occurring in biological Fish and Wildlife Service may update and publish the list of families included in the treaties from species exempted from protection of the the draft list. -

Columbiformes ~ Pterocliformes ~ Mesitornithiformes

Birds of the World part 2 Galloanseres, Neoaves: Columbea NEOGNATHAE (the rest of the birds!): Galloanseres • ORDER ANSERIFORMES – waterfowl • Family Anhimidae – screamers (3 species) • Family Anseranatidae – magpie goose (1 species) • Family Anatidae – ducks, geese, and swans (173 species) • ORDER GALLIFORMES – landfowl • Family Megapodiidae – megapodes (21 species) • Family Cracidae – chachalacas, curassows, and guans (55 species) • Family Numididae – guineafowl (6 species) • Family Odontophoridae – New World quail (34 species) • Family Phasianidae – pheasants and allies (183 species) NEOGNATHAE : Neoaves (the rest of the birds!): COLUMBEA • ORDER PODICIPEDIFORMES – Family Podicipedidae – grebes (23 species) • ORDER PHOENICOPTERIFORMES – Family Phoenicopteridae – flamingos (6 species) • ORDER COLUMBIFORMES – Family Columbidae – pigeons and doves (334 species) • ORDER PTEROCLIDIFORMES – Family Pteroclididae – sandgrouse (16 species) • ORDER MESITORNITHIFORMES – Family Mesitornithidae – mesites (3 species) NEOGNATHAE : Galloanseres • ORDER ANSERIFORMES – waterfowl • Family Anhimidae – screamers (3 species) • Family Anseranatidae – magpie goose (1 species) • Family Anatidae – ducks, geese, and swans (173 species) • ORDER GALLIFORMES – landfowl • Family Megapodiidae – megapodes (21 species) • Family Cracidae – chachalacas, curassows, and guans (55 species) • Family Numididae – guineafowl (6 species) • Family Odontophoridae – New World quail (34 species) • Family Phasianidae – pheasants and allies (183 species) southern or crested screamer