Long-Legged Pink Things

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

6-A John James Audubon, American Flamingo, 1838

JOHN JAMES AUDUBON [1785–1851] 6 a American Flamingo,1838 American Flamingo is one of the 435 hand-colored engravings that River, a major flyway for migratory birds, and eventually wan- make up John James Audubon’s monumental Birds of America, dered farther from home to comb the American frontier for issued in four volumes between 1826 and 1838. The massive unrecorded species. publication includes life-size representations of nearly five hundred Audubon’s procedure was to study and sketch a bird in its natural species of North American birds. Although Audubon was not the habitat before killing it carefully, using fine shot to minimize dam- first to attempt such a comprehensive catalog, his work departed age. His critical innovation was to then thread wire through the from conventional scientific illustration, which showed lifeless spec- specimen, allowing him to fashion a lifelike pose. He worked in imens against a blank background, by presenting the birds as they watercolor, and had completed some four hundred paintings appeared in the wild. When his pictures were first published, when he decided to publish them as a folio of prints. Failing to find some naturalists objected to Audubon’s use of dramatic action and support in Philadelphia, he sailed for England, where he became pictorial design, but these are the qualities that set his work apart lionized as “The American Woodsman.” The engraving firm and make it not only an invaluable record of early American Robert Havell and Son took on the challenge of reproducing wildlife but an unmatched work of American art. Audubon’s paintings on copper plates and tinting the resulting John James Audubon was born in Haiti and educated in France, black-and-white prints by hand. -

A Pliocene Flamingo from Mexico

June, 1944 THE WILSON BULLETIN 77 Vol. 56. No. 2 A PLIOCENE FLAMINGO FROM MEXICO BY LOYE MILLER IELD parties from the California Institute of Technology have been F fortunate in locating a variety of fossil deposits in Mexico that in- cluded bird remains. Some have been very rich in the quantity and variety of material; for example, the San Josecito Cavern of Nuevo Leon (Miller, ,1943), a deposit of Pleistocene age, yielded several thousand bird bones assigned to over forty species. The present paper deals with a collection of ten fragments, all but one of which are in- cluded in a single species. I am indebted to Dr. Chester Stock in charge of the explorations for the opportunity of working with the bird collec- tions. Dr. Alexander Wetmore has loaned comparative material, and Dr. Hildegarde Howard has been a most congenial fellow student during many conferences on the flamingoes, both Recent and Fossil. To these several colleagues my sincere thanks are offered. The ten fragments are from collecting locality No. 289, California Institute of Technology, known. as the Rincon Pliocene, Chihuahua, Mexico. Associated mammal remains include horse, camel, antelope, and carnivore species. The matrix is a fine grained silt of lightest color, without cementing material. A stiff brush serves to remove it from the well petrified bones. Unfortunately the specimens are most frag- mentary. They do, however, prove to be of interest in several respects; most notably they prove (since several speciments are from pre-volant young) that a small speciesof flamingo was present as a breeding bird. This is the earliest record for the family in America. -

Flamingo ABOUT the GROUP

Flamingo ABOUT THE GROUP Bulletin of the IUCN-SSC/Wetlands International The Flamingo Specialist Group (FSG) was established in 1978 at Tour du Valat in France, under the leadership of Dr. Alan Johnson, who coordinated the group until 2004 (see profile at www.wetlands.org/networks/Profiles/January.htm). Currently, the group is FLAMINGO SPECIALIST GROUP coordinated from the Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust at Slimbridge, UK, as part of the IUCN- SSC/Wetlands International Waterbird Network. The FSG is a global network of flamingo specialists (both scientists and non- scientists) concerned with the study, monitoring, management and conservation of the world’s six flamingo species populations. Its role is to actively promote flamingo research and conservation worldwide by encouraging information exchange and cooperation amongst these specialists, and with other relevant organisations, particularly IUCN - SSC, Ramsar, WWF International and BirdLife International. FSG members include experts in both in-situ (wild) and ex-situ (captive) flamingo conservation, as well as in fields ranging from field surveys to breeding biology, diseases, tracking movements and data management. There are currently 165 members around the world, from India to Chile, and from France to South Africa. Further information about the FSG, its membership, the membership list serve, or this bulletin can be obtained from Brooks Childress at the address below. Chair Assistant Chair Dr. Brooks Childress Mr. Nigel Jarrett Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust Slimbridge Slimbridge Glos. GL2 7BT, UK Glos. GL2 7BT, UK Tel: +44 (0)1453 860437 Tel: +44 (0)1453 891177 Fax: +44 (0)1453 860437 Fax: +44 (0)1453 890827 [email protected] [email protected] Eastern Hemisphere Chair Western Hemisphere Chair Dr. -

Trinidad & Tobago II 2019 BIRDS

Field Guides Tour Report Trinidad & Tobago II 2019 Dec 27, 2019 to Jan 5, 2020 Tom Johnson For our tour description, itinerary, past triplists, dates, fees, and more, please VISIT OUR TOUR PAGE. Each one of those red dots is a Scarlet Ibis - and look closely, you'll see a strip of pink from the American Flamingo flock at the bottom. This was our evening scene at Caroni Swamp. Photo by group member Delle Daniels. The island nation of Trinidad and Tobago provides an accessible bounty of neotropical wildlife with comfortable accommodation. Our holiday tour this year was no exception – we spent five nights at the famed Asa Wright Nature Centre in Trinidad and two nights on the sandy shores of the Atlantic on Tobago. We drank coffee and tea in the morning as the rising sun brought legions of hummingbirds and honeycreepers to the feeding station below the Asa Wright veranda, studied the mating displays of the odd Bearded Bellbird and transforming White-bearded Manakin, sought the stunning Blue-and- yellow Macaw at Nariva Swamp, enjoyed the waves of brilliant Scarlet Ibis ripple past at Caroni Swamp, and watched with excitement as Magnificent Frigatebirds tail-chased Red-billed Tropicbirds over the blue water below Little Tobago Island. There was something for everyone – for those who were taken by Neotropical birding challenges, there were Chestnut-collared and Lesser Swallow-tailed swifts to pick out of the skies above the Arima Valley and a Gray-throated Leaftosser skulking in the shadows. For those more attracted to spectacles of movement and color, we turned to the diminutive Tufted Coquettes of Asa Wright’s gardens and the jaw-droppingly pink American Flamingos striding below the river of Scarlet Ibis at Caroni Swamp. -

Wetland Birds in the Recent Fossil Record of Britain and Northwest Europe John R

Wetland birds in the recent fossil record of Britain and northwest Europe John R. Stewart 18. Dalmatian Pelican Pelecanus crispus, Deep Bay, Mai Po, Hong Kong, February 1995. Geological evidence suggests that Dalmatian Pelicans bred in Britain, and in other western European countries (including The Netherlands and Denmark), prior to and during the Iron Age. Ray Tipper. ABSTRACT Wetland habitats in Britain and other parts of western Europe have been severely depleted during the latter part of the Holocene owing principally to drainage and land reclamation. Changes in the distribution of a number of wetland bird species can be gauged from archaeological and geological site records of larger birds, whose remains are generally better preserved. Key species are discussed here, including a heron Nycticorax fenensis and a crane Grus primigenia, two extinct species named on possibly uncertain fossil evidence. We can let our minds wander back to the misty realms of fifteen hundred years ago, to a wonderful Britain which was alive with bird song from coast to coast, which sheltered wolves, bears and boars in its dark woodlands, cranes in its marshes, bustards on its heaths and beavers by its streams, and we can visualize the great pink pelican sweeping on its huge pinions over the reedy waterways which then penetrated by secret paths into the very heart of what is now Somerset. (Whitlock, 1953) © British Birds 97 • January 2004 • 33-43 33 Wetland birds in the recent fossil record f all the major habitats in northwest species, including Mute Swan Cygnus olor and Europe, wetlands may have been the Common Crane, may have become physically Omost severely depleted during the smaller owing to habitat impoverishment. -

GREATER and LESSER FLAMINGOS Phoenicopterus Ruber and Phoeniconaias Minor

GREATER AND LESSER FLAMINGOS Phoenicopterus ruber and Phoeniconaias minor Greater and Lesser Flamingos © Cliff Buckton © P & H Harris Lesser Flamingo The Lesser Flamingo Phoeniconaias minor is the smallest of the world's five flamingo species. It occurs primarily in the Rift Valley lakes of East Africa with about 4 to 5 million birds estimated, but also in small populations in Namibia/Botswana (40,000), Mauritania/Senegal (15,400), Ethiopia (8,300). The alkaline lakes of the Rift Valley are the primary feeding areas for the East Africa population. During non-breeding periods these lakes often hold almost the entire population. Huge feeding flocks of 1-2 million birds frequently gather on lakes Bogoria and Nakuru, creating one of the most stunning wildlife spectacles in the world. Although it is still the most numerous of the five species, the Lesser Flamingo is classified as globally "near threatened" due primarily to its dependence on a limited number of unprotected breeding sites and threats of proposed soda-ash mining and hydro-electric power schemes on the main breeding lakes. The question of whether there is occasional interchange between the East African and southern African populations has yet to be resolved definitely, but considerable circumstantial evidence has now been assembled to show that East African Lesser Flamingos probably do fly to Botswana to breed during periods when the Lake Makgadikgadi Salt Pans are flooded. Their migration routes, flight range and stopover places (if any) are still unknown. It is now known that Lesser Flamingos do fly during the day, at great heights, well above the normal diurnal movement of eagles, their main aerial predator. -

Flamingo Newsletter 17, 2009

ABOUT THE GROUP The Flamingo Specialist Group (FSG) is a global network of flamingo specialists (both scientists and non-scientists) concerned with the study, monitoring, management and conservation of the world’s six flamingo species populations. Its role is to actively promote flamingo research, conservation and education worldwide by encouraging information exchange and cooperation among these specialists, and with other relevant organisations, particularly the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC), the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands, the Convention on Conservation of Migratory Species (CMS), the African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbird Agreement (AEWA), and BirdLife International. The group is coordinated from the Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust, Slimbridge, UK, as part of the IUCN-SSC/Wetlands International Waterbird Network. FSG members include experts in both in-situ (wild) and ex-situ (captive) flamingo conservation, as well as in fields ranging from research surveys to breeding biology, infectious diseases, toxicology, movement tracking and data management. There are currently 286 members representing 206 organisations around the world, from India to Chile, and from France to South Africa. Further information about the FSG, its membership, the membership list serve, or this bulletin can be obtained from Brooks Childress at the address below. Chair Dr. Brooks Childress Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust Slimbridge Glos. GL2 7BT, UK Tel: +44 (0)1453 860437 Fax: +44 (0)1453 860437 [email protected] Eastern Hemisphere Chair Western Hemisphere Chair Dr. Arnaud Béchet Dr. Felicity Arengo Station biologique, Tour du Valat American Museum of Natural History Le Sambuc Central Park West at 79th Street 13200 Arles, France New York, NY 10024 USA Tel : +33 (0) 4 90 97 20 13 Tel: +1 212 313-7076 Fax : +33 (0) 4 90 97 20 19 Fax: +1 212 769-5292 [email protected] [email protected] Citation: Childress, B., Arengo, F. -

Comments on the Population Status of Chilean Flamingos at Lagoa Do Peixe National Park, Southern Brazil

Delfino and Aldana-Ardila. Flamingo 2020, pages: 21-26. Comments on the population status of Chilean flamingos at Lagoa do Peixe National Park, Southern Brazil Henrique Cardoso Delfino 1* & Oscar Maurício Aldana-Ardila 1 1 Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Instituto de Biociências, Departamento de Zoologia, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Biologia Animal, Laboratório de Ecologia e Sistemática de Aves e Mamíferos Marinhos (LABSMAR). Av. Bento Gonçalves, 9500. CEP: 91509-900, Porto Alegre, RS, Brasil. *Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract In South America, the Chilean flamingo (Phoenicopterus chilensis) is distributed from south of the Equator to southern Argentina, passing by the Brazilian coast. One of the locations where this species is present in southern Brazil is the Lagoa do Peixe National Park, between the cities of Mostardas and Tavares, in Rio Grande do Sul state. This area is a natural reserve implemented to conserve both coastal biodiversity and the many species of migratory birds that use the area in contranuptial periods. Although the flamingo is well known in the region, there is a lack, in scientific literature, of information about the population of flamingos living inside the park. In this paper, we comment on the current population and conservation status of Chilean flamingos in the Lagoa do Peixe National Park, bringing attention to the necessities to protect the park from political pressures and to increase research activity on these birds in this area. Resumen En América del Sur, el flamenco austral (Phoenicopterus chilensis) se distribuye desde el sur del Ecuador hasta el sur de Argentina, pasando por la costa brasileña. -

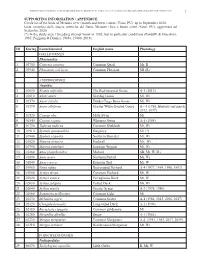

1 ID Euring Latin Binomial English Name Phenology Galliformes

BIRDS OF METAURO RIVER: A GREAT ORNITHOLOGICAL DIVERSITY IN A SMALL ITALIAN URBANIZING BIOTOPE, REQUIRING GREATER PROTECTION 1 SUPPORTING INFORMATION / APPENDICE Check list of the birds of Metauro river (mouth and lower course / Fano, PU), up to September 2020. Lista completa delle specie ornitiche del fiume Metauro (foce e basso corso /Fano, PU), aggiornata ad Settembre 2020. (*) In the study area 1 breeding attempt know in 1985, but in particolar conditions (Pandolfi & Giacchini, 1985; Poggiani & Dionisi, 1988a, 1988b, 2019). ID Euring Latin binomial English name Phenology GALLIFORMES Phasianidae 1 03700 Coturnix coturnix Common Quail Mr, B 2 03940 Phasianus colchicus Common Pheasant SB (R) ANSERIFORMES Anatidae 3 01690 Branta ruficollis The Red-breasted Goose A-1 (2012) 4 01610 Anser anser Greylag Goose Mi, Wi 5 01570 Anser fabalis Tundra/Taiga Bean Goose Mi, Wi 6 01590 Anser albifrons Greater White-fronted Goose A – 4 (1986, february and march 2012, 2017) 7 01520 Cygnus olor Mute Swan Mi 8 01540 Cygnus cygnus Whooper Swan A-1 (1984) 9 01730 Tadorna tadorna Common Shelduck Mr, Wi 10 01910 Spatula querquedula Garganey Mr (*) 11 01940 Spatula clypeata Northern Shoveler Mr, Wi 12 01820 Mareca strepera Gadwall Mr, Wi 13 01790 Mareca penelope Eurasian Wigeon Mr, Wi 14 01860 Anas platyrhynchos Mallard SB, Mr, W (R) 15 01890 Anas acuta Northern Pintail Mi, Wi 16 01840 Anas crecca Eurasian Teal Mr, W 17 01960 Netta rufina Red-crested Pochard A-4 (1977, 1994, 1996, 1997) 18 01980 Aythya ferina Common Pochard Mr, W 19 02020 Aythya nyroca Ferruginous -

The Handrearing of a Chilian Flamingo And

£; 'E (j) CJ) :§ o > .0 o (5 .c 0.. PInk Floyd The Handrearing ofa Chilian Flamingo and its Introduction to the Flock Floyd (second from right) seen as a member ofthe flock. He can be distinguished be the light by Chris Smith gray down on the headand neckand by the lighter shade ofpink on the body andwings. Shortly Animal Technician after Floyd was introduced to the flock, several pairs C!f.flamingos successfully hatched and Oklahoma City Zoological Park reared theiryoung. ink Floyd: to many people it is birds care. However, after one of the hatching, chicks stay in or near the the name of a rock band that has first eggs disappeared from the nest, nest for about the first week. After Precorded many cIa sic albums the remaining and subsequent eggs leaving the nest, chicks congregate such as "The Wall" and "The Dark Side were pulled and replaced with dummy with other chicks, forming creches or of the Moon. ' To the personnel at the eggs. The eggs were placed in incuba nursery groups. These creches can Oklahoma City Zoological Park, it is also tor at a temperature of 99.5° F. (37.5° consist of several thousand young the name of its first captive-hatched C). The hygrometer was maintained birds. Chilean Flamingo, Phoenicopterus between 82-84°F (30-31°C). The eggs Adult flamingos take turns watching chilensis. were turned five times daily. A total of over the chicks. While the chicks are in The Oklahoma City Zoo has exhib eight flamingo eggs were pulled from the nursery, the parents continue to ited Chilean Flamingos since 1966, but the nests. -

The Analysis of Destruction in Flamingo Habitat of Acigol Wetland

THE ANALYSIS OF DESTRUCTION IN FLAMINGO HABITAT OF ACIGOL WETLAND M. Karaman*, Z. D. Uca Avci, I. Papila, E. Ozelkan Istanbul Technical University, Center for Satellite Communications and Remote Sensing, Maslak, Istanbul,Turkey (muhittin, damla, emre, papila)@cscrs.itu.edu.tr Abstract: Industrial developments improve human zoologists. The spatial and temporal analyses of water life whereas it can destroy, pollute and decrease the covered areas in the basin area were distinguished by available feeding and breeding area for the animals. considering the feeding type of flamingos as wading. For Acigol Lake, being a saline shallow wetland, offers a the same time period, salt production activities were suitable feeding and breeding area on the migration compared and their effects were evaluated. way of flamingos’. Acigol Lake is the main sodium sulfate production area in Turkey. Sodium sulfate production is carried out by industrial firms and high amounts of water are pumped from lake to salt pans. In this study, spatial and temporal variation of flamingos’ feeding sites due to water pumping is investigated by using remote sensing. Dry and water covered areas were determined by using modified normalized difference water index (MNDWI). Then, the MNDWI images were classified to ‘feeding by wading’ and ‘feeding by swimming’ areas by using the in-situ depth measurements. The decreases in the lake water level during salt production period, showed the Figure 1. The picture of a dead flamingo in Tuz Lake direct effect of industry on flamingos’ feeding areas. (photo credit: Murat Ataol ) (Balkız et al.,2009) Figure 2 . The artemia salina deaths in salt pans Keywords: flamingo, Lake Acigol, MNDWI, salt lake, (Karaman, 2011) salt pans, remote sensing 2. -

Population Size and Movements of the Greater Flamingo (Phoenicopterus Roseus) in the Jaffna Peninsula, Sri Lanka: Results from a Long-Term Study

Ceylon Journal of Science 47(4) 2018: 373-378 DOI: http://doi.org/10.4038/cjs.v47i4.7555 RESEARCH ARTICLE Population size and movements of the Greater Flamingo (Phoenicopterus roseus) in the Jaffna peninsula, Sri Lanka: Results from a long-term study Chaminda S. Wijesundara1,*, Saumya Wanniarachchi1, Tharangi Hettiarachchi1, Supun Galappaththi1, Asela Weerawardhana1 and Packiyanathan Rajkumar2,3 1Department of Zoology, University of Peradeniya, Peradeniya, Sri Lanka 2Postgraduate Institute of Science, University of Peradeniya, Peradeniya, Sri Lanka 3Divisional Secretariat, Chundukkuli, Jaffna, Sri Lanka Received:12/05/2018; Accepted:02/08/2018 Abstract: The Greater Flamingo (Phoenicopterus roseus) is an and western Africa, from east Africa to South Africa and uncommon migrant bird species found in Sri Lanka, and is a major Madagascar, and east to Kazakhstan and through Middle attraction among avitourists. Jaffna Peninsula, Mannar Island, and East to India and Sri Lanka (Primack, 2010; del Hoyo et the southeastern coastal areas are the known strongholds of this al., 2017). In Sri Lanka, it is mainly found in the northern species in Sri Lanka. Previous studies on this species in the Jaffna parts of the island (Wijesundara et al., 2017b), where, in Peninsula are limited, most probably due to the inaccessibility some areas such as Jaffna region, it is one of the most of the area during the three-decade long civil war. Hence, the abundant migratory bird species (Wijesundara et al., objectives of the present study were to determine the population 2016). Even though it is generally recognized as a migrant size and movements of the Greater Flamingo in major flocking species, a large number can be seen year-round in the areas in the Jaffna Peninsula.