Studies in the Bible and Antiquity Volume 5

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Book of Common Prayer

The Book of Common Prayer and Administration of the Sacraments and Other Rites and Ceremonies of the Church Together with The Psalter or Psalms of David According to the use of The Episcopal Church Church Publishing Incorporated, New York Certificate I certify that this edition of The Book of Common Prayer has been compared with a certified copy of the Standard Book, as the Canon directs, and that it conforms thereto. Gregory Michael Howe Custodian of the Standard Book of Common Prayer January, 2007 Table of Contents The Ratification of the Book of Common Prayer 8 The Preface 9 Concerning the Service of the Church 13 The Calendar of the Church Year 15 The Daily Office Daily Morning Prayer: Rite One 37 Daily Evening Prayer: Rite One 61 Daily Morning Prayer: Rite Two 75 Noonday Prayer 103 Order of Worship for the Evening 108 Daily Evening Prayer: Rite Two 115 Compline 127 Daily Devotions for Individuals and Families 137 Table of Suggested Canticles 144 The Great Litany 148 The Collects: Traditional Seasons of the Year 159 Holy Days 185 Common of Saints 195 Various Occasions 199 The Collects: Contemporary Seasons of the Year 211 Holy Days 237 Common of Saints 246 Various Occasions 251 Proper Liturgies for Special Days Ash Wednesday 264 Palm Sunday 270 Maundy Thursday 274 Good Friday 276 Holy Saturday 283 The Great Vigil of Easter 285 Holy Baptism 299 The Holy Eucharist An Exhortation 316 A Penitential Order: Rite One 319 The Holy Eucharist: Rite One 323 A Penitential Order: Rite Two 351 The Holy Eucharist: Rite Two 355 Prayers of the People -

Isaiah Commentaries & Sermons

Isaiah Commentaries & Sermons SONG OF SOLOMON JEREMIAH NEWEST ADDITIONS: Verse by verse Commentary on Isaiah 53 (Isaiah 52:13-53:12) - Bruce Hurt Verse by verse Commentary on Isaiah 35 - Bruce Hurt ISAIAH RESOURCES Commentaries, Sermons, Illustrations, Devotionals Click chart to enlarge Click chart to enlarge Chart from recommended resource Jensen's Survey of the OT - used by permission Another Isaiah Chart see on right side Caveat: Some of the commentaries below have "jettisoned" a literal approach to the interpretation of Scripture and have "replaced" Israel with the Church, effectively taking God's promises given to the literal nation of Israel and "transferring" them to the Church. Be a Berean Acts 17:11-note! ISAIAH ("Jehovah is Salvation") See Excellent Timeline for Isaiah - page 39 JEHOVAH'S JEHOVAH'S Judgment & Character Comfort & Redemption (Isaiah 1-39) (Isaiah 40-66) Uzziah Hezekiah's True Suffering Reigning Jotham Salvation & God Messiah Lord Ahaz Blessing 1-12 13-27 28-35 36-39 40-48 49-57 58-66 Prophecies Prophecies Warnings Historical Redemption Redemption Redemption Regarding Against & Promises Section Promised: Provided: Realized: Judah & the Nations Israel's Israel's Israel's Jerusalem Deliverance Deliverer Glorious Is 1:1-12:6 Future Prophetic Historic Messianic Holiness, Righteousness & Justice of Jehovah Grace, Compassion & Glory of Jehovah God's Government God's Grace "A throne" Is 6:1 "A Lamb" Is 53:7 Time 740-680BC OTHER BOOK CHARTS ON ISAIAH Interesting Facts About Isaiah Isaiah Chart The Book of Isaiah Isaiah Overview Chart by Charles Swindoll Visual Overview Introduction to Isaiah by Dr John MacArthur: Title, Author, Date, Background, Setting, Historical, Theological Themes, Interpretive Challenges, Outline by Chapter/Verse. -

İSRAİL ISO 9001 BELGESİ VE FİYATI Kalite Yönetim Sistemi Standardı' Nın Hazırlanışı Mantalite Ve Metodoloji

İSRAİL ISO 9001 BELGESİ VE FİYATI Kalite Yönetim Sistemi Standardı’ nın hazırlanışı mantalite ve metodoloji olarak belirli coğrafyaları içerecek şekilde olmamaktadır. ISO-Uluslararası Standart Organizasyonu standartları global kullanım amaçlı hazırlamakta ve bu standartlarla küresel bir standart yapısı kurmayı hedeflemektedir. Bu hedefle kullanıma sunulan uluslararası kalite yönetim sistemi standardının tüm dünyada kriteri ve uygulaması aynı fakat standart dili farklıdır. ISO 9001 Kalite Yönetim Sistemi Belgesi ve fiyatının uygulama kriteri İSRAİL Ülkesi ve şehirlerin de tamamen aynıdır. Ancak her kuruluşun maliyet ve proses yapıları farklı olduğu için standart uygulaması ne kadar aynı da olsa fiyatlar farklılık göstermektedir. İSRAİL Ülkesinde kalite yönetim sistemi uygulaması ve standart dili İSRAİLca olarak uyarlanmıştır. İSRAİL Standart Kurumunun, standardı İSRAİL diline uyarlaması ile bu ülke bu standardı kabul etmiş, ülke coğrafyasında yer alan tüm şehirler ve kuruluşları için kullanımına sunmuştur. İSRAİL ISO 9001 belgesi ve fiyatı ilgili coğrafi konum olarak yerleşim yerleri ve şehirleri ile ülke geneli ve tüm dünya genelinde geçerli, kabul gören ve uygulanabilir bir kalite yönetim sistemi standardı olarak aşağıda verilen şehirleri, semtleri vb. gibi tüm yerel yapısında kullanılmaktadır. ISQ-İntersistem Belgelendirme Firması olarak İSRAİL ülkesinin genel ve yerel coğrafyasına hitap eden global geçerli iso 9001 belgesi ve fiyatı hizmetlerini vermekte olduğumuzu kullanıcılarımızın bilgisine sunmaktayız. İSRAİL ISO 9001 belgesi fiyatı ISQ belgelendirme yurt dışı standart belge fiyatı ile genellikle aynıdır. Ancak sadece denetçi(ler) yol, konaklama ve iaşe vb. masrafı fiyata ilave edilebilir. Soru: İSRAİL ’ daki ISO 9001 ile başka ülkelerdeki ISO 9001 aynı mıdır? Cevap: Evet. Uluslararası iso 9001 standardı Dünya’ nın her yerinde aynıdır, sadece fiyatları değişiklik gösterir. Ülke coğrafyasının büyüklüğü, nüfusu, sosyal yapısı vb. -

Jumalan Kasvot Suomeksi. Metaforisaatio Ja Erään

JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 82 Maria Kela Jumalan kasvot suomeksi Metaforisaatio ja erään uskonnollisen ilmauksen synty JYVÄSKYLÄN YLIOPISTO JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 82 Maria Kela Jumalan kasvot suomeksi Metaforisaatio ja erään uskonnollisen ilmauksen synty Esitetään Jyväskylän yliopiston humanistisen tiedekunnan suostumuksella julkisesti tarkastettavaksi yliopiston Villa Ranan Blomstedtin salissa joulukuun 15. päivänä 2007 kello 12. JYVÄSKYLÄN YLIOPISTO JYVÄSKYLÄ 2007 Jumalan kasvot suomeksi Metaforisaatio ja erään uskonnollisen ilmauksen synty JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 82 Maria Kela Jumalan kasvot suomeksi Metaforisaatio ja erään uskonnollisen ilmauksen synty JYVÄSKYLÄN YLIOPISTO JYVÄSKYLÄ 2007 Editors Aila Mielikäinen Department of Languages Irene Ylönen, Marja-Leena Tynkkynen Publishing Unit, University Library of Jyväskylä Jyväskylä Studies in Humanities Editorial Board Editor in Chief Heikki Hanka, Department of Art and Culture Studies, University of Jyväskylä Petri Karonen, Department of History and Ethnology, University of Jyväskylä Matti Rahkonen, Department of Languages, University of Jyväskylä Petri Toiviainen, Department of Music, University of Jyväskylä Minna-Riitta Luukka, Centre for Applied Language Studies, University of Jyväskylä Raimo Salokangas, Department of Communication, University of Jyväskylä Cover picture by Jyrki Kela URN:ISBN:9789513930691 ISBN 978-951-39-3069-1 (PDF) ISBN 978-951-39-3008-0 (nid.) ISSN 1459-4331 Copyright ©2007 , by University of Jyväskylä Jyväskylä University Printing House, Jyväskylä 2007 ABSTRACT Kela, Maria God’s face in Finnish. Metaphorisation and the emergence of a religious expression. Jyväskylä: University of Jyväskylä, 2007, 275 p. (Jyväskylä Studies in Humanities ISSN 1459-4331; 82) ISBN 978-951-39-3069-1 (PDF), 978-951-39-3008-0 (nid.) English summary Diss. The objective of this study is to reveal, how a religious expression is emerged through the process of metaphorisation in translated biblical language. -

Shadows Over the Land Without Shade: Iconizing the Israeli Kibbutz in the 1950S, Acting-Out Post Palestinian-Nakba Cultural Trauma

Volume One, Number One Shadows over the Land Without Shade: Iconizing the Israeli Kibbutz in the 1950s, acting-out post Palestinian-Nakba Cultural Trauma Lior Libman Abstract: The kibbutz – one of Zionism's most vital forces of nation-building and Socialist enterprise – faced a severe crisis with the foundation of the State of Israel as State sovereignty brought about major structural, political and social changes. However, the roots of this crisis, which I will describe as a cultural trauma, are more complex. They go back to the pioneers' understanding of their historical action, which emanated arguably from secularized and nationalized Hasidic theology, and viewed itself in terms of the meta-historical Zionist-Socialist narrative. This perception was no longer conceivable during the 1948 war and thereafter. The participation in a war that involved expulsion and killing of civilians, the construction of new kibbutzim inside emptied Palestinian villages and confiscation by old and new kibbutzim of Palestinian fields, all caused a fatal rift in the mind of those who saw themselves as fulfilling a universal humanistic Socialist model; their response was total shock. This can be seen in images of and from the kibbutz in this period: in front of a dynamic and troublesome reality, the Realism of kibbutz-literature kept creating pastoral-utopian, heroic-pioneering images. The novel Land Without Shade (1950) is one such example. Written by the couple Yonat and Alexander Sened, it tells the story of the establishment of Kibbutz Revivim in the Negev desert in the 1940s. By a symptomatic reading of the book’s representation of the kibbutz, especially in relation to its native Bedouin neighbors and the course of the war, I argue that the iconization of the kibbutz in the 1950s is in fact an acting-out of the cultural trauma of the kibbutz, the victimizer, who became a victim of the crash of its own self-defined identity. -

End-Time Bible Prophecies

End-Time Bible Prophecies Operation Tribulation Rescue Issue Date: 2 October 2018 Contents 1. Introduction Old Testament 2. 2 Chronicles 36 3. Psalms 47 4. Isaiah 2, 4, 9, 11, 13-14, 17, 19, 23-27, 29-30, 32, 34-35, 56, 60-61, 63, 65-66 5. Jeremiah 23, 25, 29-33, 50-51 6. Ezekiel 11, 20, 28, 34, 36-48 7. Daniel 2, 7-12 8. Joel 1-3 9. Amos 9 10. Obadiah 1 11. Micah 2, 4 12. Zephaniah 1, 3 13. Zechariah 1-8, 12-14 14. Malachi 4 New Testament 15. Matthew 19, 24-25, 28 16. Mark 13 17. Luke 12, 17, 21 18. John 14 19. Acts 1-2 20. Romans 11 21. 1 Corinthians 15 22. Philippians 3 23. 1 Thessalonians 1-5 24. 2 Thessalonians 1-2 25. 2 Timothy 3 26. Titus 2 27. Hebrews 1 28. 2 Peter 3 29. 1 John 2, 4 30. 2 John 1 31. Revelation 1-22 End-Time Topics 32. End Times Defined 33. Rebirth of Israel 34. The Rapture 35. Ezekiel 38 Battle – Nations Attack Israel … God Destroys Them 36. The Antichrist (Beast) 37. Peace Treaty Between Israel and Antichrist 38. The Great Tribulation 39. Jewish Temple Rebuilt in Jerusalem 40. Two Prophets in Israel … Killed (Rise from the Dead) 41. Mark of the Beast and False Prophet 42. God’s 21 Judgments 43. 144,000 Jews Commissioned by God for His Service 44. Babylon the Great 45. Jesus’ Words (and others) About the End Times 46. Armageddon (Judgment Day) 47. -

Aufstände in Galiläa

Online-Texte der Evangelischen Akademie Bad Boll Aufstände in Galiläa Schriftliche Berichte und archäologische Funde Dr. Yinon Shivtiel Ein Beitrag aus der Tagung: Bauern, Fischer und Propheten. Neues aus Galiläa zur Zeit Jesu Archäologie und Theologie im Neuen Testament Bad Boll, 7. - 8. Mai 2011, Tagungsnummer: 500211 Tagungsleitung: Dr. Thilo Fitzner _____________________________________________________________________________ Bitte beachten Sie: Dieser Text ist ausschließlich zum persönlichen, privaten Gebrauch bestimmt. Jede weitere Vervielfältigung und Verbreitung bedarf der ausdrücklichen Genehmigung des Urhebers/der Urheberin bzw. der Evangelischen Akade- mie Bad Boll. © 2011 Alle Rechte beim Autor/bei der Autorin dieses Textes Eine Stellungnahme der Evangelischen Akademie Bad Boll ist mit der Veröffentlichung dieses Textes nicht ausge- sprochen. Evangelische Akademie Bad Boll Akademieweg 11, D-73087 Bad Boll E-Mail: [email protected] Internet: www.ev-akademie-boll.de Cliff Settlements, Shelters and Refuge Caves in the Galilee1 Yinon Shivtiel2 The1existence of intricate systems of intercon- nected refuge caves in2the Judean Desert has been known for a long time, and has been the subject of many publications, including one in this volume.3 These systems were attributed by researchers to the period of the Bar Kokhba rebellion. One of the researchers suggested in his article that over 20 similar systems existed in the Galilee (Shahar 2003, 232-235). The pur- pose of this article is to show that the cave sys- tems in the Galilee served not only as places Figure 1. Two coins from Akhbarah. of refuge, but also as escape routes for local villagers. The common denominator of these the time-range and the simultaneity of prepa- systems was their complexity, as compared rations of the caves for refuge suggest that the with cliff-top caves, as they are currently acces- methods of enlarging and preparing these caves sible only by rappelling. -

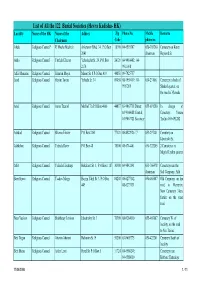

List of All the 122 Burial Societies (Hevra Kadisha- HK) Locality Name of the HK Name of the Addres Zip Phone No

List of All the 122 Burial Societies (Hevra Kadisha- HK) Locality Name of the HK Name of the Addres Zip Phone No. Mobile Remarks Chairman Code phone no. Afula Religious Council* R' Moshe Mashiah Arlozorov Blvd. 34, P.O.Box 18100 04-6593507 050-303260 Cemetery on Keren 2041 chairman Hayesod St. Akko Religious Council Yitzhak Elharar Yehoshafat St. 29, P.O.Box 24121 04-9910402; 04- 2174 9911098 Alfei Menashe Religious Council Shim'on Moyal Manor St. 8 P.O.Box 419 44851 09-7925757 Arad Religious Council Hayim Tovim Yehuda St. 34 89058 08-9959419; 08- 050-231061 Cemetery in back of 9957269 Shaked quarter, on the road to Massada Ariel Religious Council Amos Tzuriel Mish'ol 7/a P.O.Box 4066 44837 03-9067718 Direct; 055-691280 In charge of 03-9366088 Central; Cemetery: Yoram 03-9067721 Secretary Tzefira 055-691282 Ashdod Religious Council Shlomo Eliezer P.O.Box 2161 77121 08-8522926 / 7 053-297401 Cemetery on Jabotinski St. Ashkelon Religious Council Yehuda Raviv P.O.Box 48 78100 08-6714401 050-322205 2 Cemeteries in Migdal Tzafon quarter Atlit Religious Council Yehuda Elmakays Hakalanit St. 1, P.O.Box 1187 30300 04-9842141 053-766478 Cemetery near the chairman Salt Company, Atlit Beer Sheva Religious Council Yaakov Margy Hayim Yahil St. 3, P.O.Box 84208 08-6277142, 050-465887 Old Cemetery on the 449 08-6273131 road to Harzerim; New Cemetery 3 km. further on the same road Beer Yaakov Religious Council Shabbetay Levison Jabotinsky St. 3 70300 08-9284010 055-465887 Cemetery W. -

Religious and Social Meanings of the Holy Land Ways of Knowing 2312

Religious and Social Meanings of the Holy Land Ways of Knowing 2312 Chancey and Lander JTerm 2017 [email protected] and [email protected] Jan. 6-18, 2017 Course Description The current state of Israel comprises regions that the three Abrahamic religions have regarded as holy for centuries. Although the concept of a “Holy Land” permeates ancient Jewish writings, it was early Christian pilgrims who first employed the biblical term “Holy Land” to describe the territory of the Bible. In the seventh century, Islam also forged a connection to this area, more specifically Jerusalem, regarding it as the site of the prophet Muhammed’s night-time journey (‘Isra) to heaven. Through archaeological and site fieldtrips, readings, and lectures by experts in the field, students will investigate the diverse meanings of the Holy Land to the adherents of the various traditions who have regarded the region as religiously significant for more than three millennia. Students will learn how the two disciplines of archaeology and religious studies combine to inform a deeper understanding of the Holy Land than a single disciplinary study. Students will also explore the complexity of daily life in the modern state of Israel. Student Learning Outcomes Ways of Knowing 1. Students will demonstrate knowledge of more than one disciplinary practice. 2. Students will explain how bringing more than one practice to an examination of the course topic contributes to knowing about that topic. Philosophical/Religious/Ethical Inquiry, level I 1. Students will be able to describe and explain some of the general features and principal theoretical methods of one of the fields of philosophy, religious studies, or ethics. -

Isaiah 25, Concluding Cantata: Isaiah's Song

Isaiah 25, Concluding Cantata: Isaiah's Song Isaiah 25, Concluding Cantata: Isaiah's Song Overview Structure of the Cantata The fundamental dynamic is an alternation of scenes of judgment and of rejoicing. The section falls into two parts. In the first part, two major sections of judgment (24:1-12; 16b-22) alternate with a distant echo of . ארץ ”songs of praise (13-16a, cf. 23). This section is marked by frequent1 mention of the “earth In the second part, the singers draw near, and we hear three songs, each followed by a description of the events of which they sing: • Isaiah's Song (25:1-5) and a description of what will happen “in this mountain” (6-12) • Judah's song (26:1-19) and advice and description for the coming judgment (26:20-27:1) • The Lord's song (27:2-5) and description of the coming restoration of his people and judgment on the unbelievers (6-13). 25:1-12, Isaiah's Song and Expectation The major division is between address to the Lord in the second person (1-5) and description of the Lord in the third person (6-10). 1-5, Song The song alternates between statements of praise and the reasons for praise. First Isaiah himself praises the Lord, giving as reason the Lord's sovereign judgments. Then he states that those who were Israel's oppressors will glorify and fear the Lord. This time the reason is the Lord's protection of his people. 25:1 O LORD, thou art my God; I will exalt thee, I will praise thy name;--The verse is an adaptation of Ps 118:28, which in turn (together with v. -

First Reading Isaiah 25:6A, 7-9 a Reading from the Book of The

First Reading Isaiah 25:6a, 7-9 A reading from the Book of the Prophet Isaiah On this mountain the Lord of hosts will provide for all peoples. On this mountain he will destroy the veil that veils all peoples, The web that is woven over all nations; he will destroy death forever. The Lord God will wipe away the tears from all faces; The reproach of his people he will remove from the whole earth; for the Lord has spoken. On that day it will be said: “Behold our God, to whom we looked to save us! This is the Lord for whom we looked; let us rejoice and be glad that he has saved us!” Pause and look up at the congregation. Then say: The Word of the Lord. First Reading Isaiah 40:1-5 A reading from the prophet Isaiah Comfort, O comfort my people, says your God. Speak tenderly to Jerusalem, and cry to her that she has served her term, that her penalty is paid, that she has received from the Lord’s hand double for all her sins. A voice cries out: “In the wilderness prepare the way of the Lord, make straight in the desert a highway for our God. Every valley shall be lifted up, and every mountain and hill be made low; the uneven ground shall become level, and the rough places a plain. Then the glory of the Lord shall be revealed, and all people shall see it together, for the mouth of the Lord has spoken.” Pause and look up at the congregation. -

Hukkok Hukok Hul Huldah I. Hebrew Bible/Old Testament

519 Hukkok 520 what extent this attitude is expressed in the Hui not Hukok but Helkath. Horvat Gamum, located theological discourse is a subject for further re- on a steep hill at the junction of Misgav, may have search. been the biblical city of Hukuk. It is near the mod- Another type of (possible) encounter with Chris- ern kibbutz of Hukuk. tian traditions can be traced in Hui myths and leg- Bibliography: ■ Knoppers, G. N., I Chronicles 1–9 (AB 12; ends. In particular, legends about the first ancestors New York 2004) 461–62. of Hui Muslims, Adam and Haowa (biblical Eve; in Joseph Titus Muslim tradition H awwā), can be read as compila- tions of Muslim (qurānic), Christian (biblical), and Chinese narrative patterns under the strong influ- Hul ence of oral traditions. This interpretation, how- The name “Hul” (MT Ḥwl; LXX υλ, in other man- ever, depends on the methodology employed – uscripts – e.g., the SP – Ḥywl; etymology uncertain) alternative structuralist or evolutionary inter- occurs as an eponym in the genealogies of Gen 10 pretations have been proposed that do not involve and 1 Chr 1. Whereas according to Genesis Hul was the hypothesis of the transmission of myths and the second son of Aram and the grandson of Seth legends. However, evidence of anti-Catholic polem- (Gen 10 : 23), 1 Chronicles states that Hul was the ics in a few legends is uncontested, perhaps result- seventh son of Shem (1 Chr 1 : 17). Most commenta- ing from the influence of Muslims who were resist- tors attribute this discrepancy to a scribal error, ing the Qing state and its Christian protégés during where the Chronicler accidentally omitted the rebellions (Li/Luckert: 7–33).