Ambrose Bierce

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1. Hand Tools 3. Related Tools 4. Chisels 5. Hammer 6. Saw Terminology 7. Pliers Introduction

1 1. Hand Tools 2. Types 2.1 Hand tools 2.2 Hammer Drill 2.3 Rotary hammer drill 2.4 Cordless drills 2.5 Drill press 2.6 Geared head drill 2.7 Radial arm drill 2.8 Mill drill 3. Related tools 4. Chisels 4.1. Types 4.1.1 Woodworking chisels 4.1.1.1 Lathe tools 4.2 Metalworking chisels 4.2.1 Cold chisel 4.2.2 Hardy chisel 4.3 Stone chisels 4.4 Masonry chisels 4.4.1 Joint chisel 5. Hammer 5.1 Basic design and variations 5.2 The physics of hammering 5.2.1 Hammer as a force amplifier 5.2.2 Effect of the head's mass 5.2.3 Effect of the handle 5.3 War hammers 5.4 Symbolic hammers 6. Saw terminology 6.1 Types of saws 6.1.1 Hand saws 6.1.2. Back saws 6.1.3 Mechanically powered saws 6.1.4. Circular blade saws 6.1.5. Reciprocating blade saws 6.1.6..Continuous band 6.2. Types of saw blades and the cuts they make 6.3. Materials used for saws 7. Pliers Introduction 7.1. Design 7.2.Common types 7.2.1 Gripping pliers (used to improve grip) 7.2 2.Cutting pliers (used to sever or pinch off) 2 7.2.3 Crimping pliers 7.2.4 Rotational pliers 8. Common wrenches / spanners 8.1 Other general wrenches / spanners 8.2. Spe cialized wrenches / spanners 8.3. Spanners in popular culture 9. Hacksaw, surface plate, surface gauge, , vee-block, files 10. -

Le Creusot Steam Hammer MEN in SHEDS

THE ORIGINAL MAGAZINE FOR MODEL ENGINEERS Vol. 220 No. 4583 • 30 March - 12 April 2018 Join our online community www.model-engineer.co.uk MEN IN Perpetual Motion SHEDS Le Creusot A Wooden Steam Traction Hammer Engine COVER FEATURE Electric Steam ENGINEERING GROUP Carriage £3.99 527 Published by MyTimeMedia Ltd. Suite 25S, Eden House, Enterprise Way, Edenbridge, Kent TN8 6HF +44 (0)1689 869840 www.model-engineer.co.uk 508 SUBSCRIPTIONS UK - New, Renewals & Enquiries Tel: 0344 243 9023 Email: [email protected] USA & CANADA - New, Renewals & Enquiries Tel: (001)-866-647-9191 REST OF WORLD - New, Renewals & Enquiries Tel: +44 1604 828 748 Email: [email protected] Vol. 220 No. 4583 30 March - 12 April 2018 CURRENT AND BACK ISSUES Tel: 01795 662976 Website: www.mags-uk.com 488 SMOKE RINGS 508 THE ENV AERO ENGINE News, views and comment on Stephen Wessel continues an occasional series EDITORIAL the world of model engineering. on the construction of an elusive prototype. Editor: Diane Carney Tel: +44 (0)1539 564750 489 SIX INCH OLDSMOBILE 511 A SIMPLE BOILER TEST RIG Email: [email protected] David Tompkins describes his electrically Tony Bird describes how you can test PRODUCTION driven half size Oldsmobile Curved Dash your small boiler for minimal cost. Designer: Yvette Green horseless carriage. Illustrator: Grahame Chambers 514 BOOK REVIEW Retouching Manager: Brian Vickers 492 THE INQUISITIVE FIDDLER Ad Production: Andy Tompkins Mitch Barnes shares some salutary lessons for 515 THE UNSEEN STUART S50 those who, like him, have decided to fiddle with Russell Franklin explains how being blind did not ADVERTISING a model on a whim. -

Automatic Hydroheater® Operation and Technical Manual

Version 2.2 Automatic Hydroheater® Operation and Technical Manual The Leader in Engineered Liquid Heating Systems Hydro-Thermal Corporation Waukesha, Wisconsin Phone 262-548-8900 | toll-free 800-952-0121 www.hydro-thermal.com Version 2.2 Automatic Hydroheater® 1 GENERAL 2 1.1 Purpose of the Manual 2 1.2 Series Designations 2 1.3 Theory of Operation 2 2 SAFETY PRECAUTIONS 4 2.1 General 4 2.2 Specific 4 3 INSTALLATION 5 3.1 General 5 3.2 Before Installing 5 3.3 Installation 8 3.4 Control Instrumentation 10 3.5 Special Installation Requirements for Operating Temperatures Above 212°F (100°C) 13 3.6 Suggested Optional Accessories 14 4 OPERATION 15 4.1 Pre-start Checklist 15 4.2 Operation 15 5 TROUBLE SHOOTING 18 5.1 Trouble, Probable Causes and Suggested Remedies 18 6 MAINTENANCE 20 6.1 Periodic Service 20 6.2 Disassembly and Re-Assembly of Series M103 Through M110 Hydroheaters for Parts Replacement (Figure 10) 21 6.3 Disassembly and Re-Assembly of K410 Through K412 Hydroheaters for Parts Replacement (See Figure 11) 27 6.4 Disassembly and Re-Assembly of Series K413, K414, K415, K416, and K417 Hydroheaters (See Figure 12) 31 7 ILLUSTRATED PARTS LIST 37 7.1 "M" Series Hydroheaters 37 7.2 "K" Series Automatic Hydroheaters (Models K410 through K412) 39 7.3 "K" Series Automatic Hydroheaters (Models K413 through K417) 41 1 Version 2.2 Automatic Hydroheater® 1 General 1.1 Purpose of the Manual This manual is intended to provide the information necessary to correctly install, operate, troubleshoot, and maintain the Hydroheater. -

MRM & VPS Shock Isolation Systems for Forging Hammers

VVIBROIBRO/DDYNAMICYNAMICS ® vibration and shock isolation systems MMRMRM™ & VPSVPS™ ShockShock IIsolationsolation SystemsSystems forfor FForgingorging HammersHammers Forging Hammer Isolation Vibro/Dynamics began producing isolation systems for forging hammers in 2002 after receiving numerous requests for an improved mounting system from hammer builders and forging producers. Vibration and shock isolation of forging hammers is very difficult due to their large masses and extreme shock forces. Vibro/Dynamics first developed the FS Series Coil Spring Isolators with viscous fluid dampers and then followed with the development of MRM™ and VPS™ Elastomeric Isolation System. Both types have proven to be very effective in isolating hammer and shock forces. Coil spring and viscous damper units provide the greatest isolation performance, but have higher initial cost, more expensive foundations, and potential maintenance issues. The viscous dampers in the spring isolators are difficult to protect if a pit should flood; a situation usually requiring the replacement of the damper fluid. Some competitive damper designs have leaked due to the cracks developing in the damper tube walls, which requires the removal and repair of the spring isolators. As a result, the MRM and VPS Systems has become an accepted standard for FSV20 and FSX20 Viscous Damped Spring Mounts vibration and shock isolation around the world. They offer superior isolation performance over timber and pad systems without the larger inertia mass, flooding issues, and higher maintenance cost associated with coil spring isolator systems. They are easy to install and maintain and have proven to be durable. This document seeks to address the technical issues involved in the isolation of forging hammers. -

Steam Handbook

Products Solutions Services Steam Handbook An introduction to steam generation and distribution 1 Steam Handbook An introduction to steam generation and distribution Dr. Ian Roberts Phillip Stoor Michael Carr Dr. Rainer Höcker Oliver Seifert 2 Endress+Hauser – Steam Handbook Impressum Publisher Endress+Hauser Flowtec AG, CH-4153 Reinach/BL Editor in chief Thomas Stauss Editorial team Michael Carr, Dr. Rainer Höcker, Dr. Ian Roberts, Romeo Rocchetti, Oliver Seifert, Thomas Stauss, Phillip Stoor Illustrations Kodotec (Lörrach, Germany) Layout, set Beatrice Meyer Steam Handbook, 1st Edition 2017 © Copyright 2017 by: Endress+Hauser Flowtec AG, CH-4153 Reinach/BL All rights reserved. This work is copyright protected in its entirety. All use in breach of copyright laws without the express permission of the publisher is forbidden. Duplication, translation, microfilming, storage and processing in any form of electronic media is prohibited. 3 Contents 5 Foreword 37 How steam moves 5 What this document is about? (simple explanation) 5 Who this document is for? 5 How to use the document? 41 On the motion of steam (detailed explanation) 7 A short history of 55 Some hazards of steam boiler designs 55 Boiling liquid expanding vapor explosion (BLEVE) 11 Why use steam? 56 Column collapse water hammer 11 What is steam used for? 59 Sub-cooled condensate induced 12 Where is steam used? water hammer 61 Flash steam explosion 13 A generic steam system 61 Overpressure in the distribution system 17 Types of industrial 61 Overpressure (inside a pressure vessel) -

THE STEAM BOILER, by Joseph HARRISON~Jr., Philadelphia

THE STEAM BOILER. 89 THE STEAM BOILER, By JosEPH HARRISON~Jr., Philadelphia. 0]~ all the elements that have been pressed into man's service, to increase his comforts and conveniences, water turned into steam holds a most important place. And strange as it may appear to the unin- formed, it might almost be said, that the steam-engine as matured by James Watt, came from his hands nearly perfect in principle, and, like Minerva from the brain of Jupiter, fully armed and ready to do battle in the varied fields in which it has since been employed. James Watt knew all, and actedwlth a knowledge of all, or nearly all, the principles that are now known. The main improvements in the steam- engine of our time, consist-in a better and simpler arrangement and proportions of parts, better material, better workmanship, and vastly increased size. Many of its better qualities are the result of improved means of manufacture in the use of the steam-hammer,--the planlng machine, slotting machine, etc., etc., which with equally improved quality of material, has enabled the steam-engine builder to do such work, as could not have been done under a less improved system, and for which Watt might have sighed in vain. Not so the steam-boiler. It, from the very ~irst application of steam as a ttseful agent, has been the constant trouble of the engine-builder, and the engine user, the great source of anxiety, danger and expense. The first patent regularly issued in England for a steam-boiler, dates about a century back, and from that time to this, patents for new de- signs or improvements, numbering thousands, have been issued in Eng- land,--on the continent of Europe, and in this country. -

CHARLESTOWN NAVY YARD, CHAIN FORGE (Smithery) (Building 105)

HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD CHARLESTOWN NAVY YARD, CHAIN FORGE (Smithery) (Building 105) HAER No. MA-90-3 Location: Charlestown Navy Yard, Boston, Suffolk County, Massachusetts Building 105 is located at latitude: 42.376258 and longitude: -71.052419. The coordinate represents the structure’s southwest corner. This coordinate was obtained on August 1, 2013, using Google Earth imagery dated April 9, 2013. Building 105 has no restriction on its release to the public. Present Owner: Boston Redevelopment Authority (BRA) owns Building 105, but the National Park Service owns the machines still in the building. Present Use: Not in use. Significance: The Charlestown Navy Yard’s Chain Forge is significant for its role as the leading manufacturer of anchor chain and anchors for the U.S. Navy in the twentieth century, as well as for the innovations in chain design and manufacture developed by its employees. In particular, the invention of Die-Lock chain by yard employees Albert M. Leahy, Carlton G. Lutts, and James Reid resulted in the designation of Die-Lock chain as the U.S. Navy’s standard and the Charlestown Navy Yard as the U.S. Navy’s supplier. Although production ceased in the 1970s with the closure of the navy yard, the forge retains a nearly complete inventory of the forges, hammers, presses, and other machinery necessary for production. In addition, there are a number of unique extant machines, such as the 1917 Tinius Olsen chain testing machine, one of only two built, and the nearly complete assembly plant for 4-3/4" Die-Lock chain. Historian: Justine Christianson, HAER Historian, 2013-2014 Project Information: The Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) is a long- range program that documents and interprets historically significant engineering sites and structures throughout the United States. -

232200 Steam and Condensate Piping and Pump Systems

CONSULTANT PROCEDURES & DESIGN GUIDELINES UNIVERSITY OF MISSOURI 232200 Steam and Condensate Piping and Pump Systems GENERAL: Steam and condensate piping and pump systems included in this document are for building systems starting at the pressure reducing station (PRV). DESIGN GUIDELINES: A. Design General 1. Definitions: 1.1 Low pressure steam is 15 psig or less. 1.2 High pressure steam is above 15 psig. 2. Campus Systems: 1.1. MU: The steam distribution system operates at 60 psig and 400 F degrees. All equipment using campus steam must be capable of using steam at a temperature of 350F degrees. Confirm this with the Project Manager. 1.2 Kansas City: Cooling Season: The steam distribution system operates as a single system at a common pressure of 10 to 15 psig. The system is supplied from one 300 hp boiler in Spencer Chemistry. Heating Season: The steam distribution system is decoupled at SMH 2. The distribution system east of SMH 2 is operated at 15 psig from one 600 hp boiler in Spencer Chemistry. The line to Flarsheim is supplied from Miller Nichols at 15 psig when ambient temperature is above 40 F and at 50 psig when ambient temperature is below 40 F. The lines west of Miller Nichols are supplied from Miller Nichols at 10 to 15 psig. 3. ALL steam used in heating systems will be used at a reduced pressure of 15 psig or less. Designer shall calculate the pressure required as indicated below. A working pressure of 5 to 8 psig is preferred. 4. High pressure steam may be used in a process heating application (autoclaves, cagewashers). -

Metal Forming Process

METAL FORMING PROCESS Unit 1:Introduction and concepts Manufacturing Processes can be classified as i) Casting ii) Welding iii) Machining iv)Mechanical working v) Powder Metallurgy vi)Plastic Technology etc., In Mechanical working Process the raw material is converted to a given shape by the application of external force. The metal is subjected to stress.It is a process of changing the shape and size of the material under the influence of external force or stress.Plastic Deformation occurs. Classification of Metal Working Processes 1. General classification i. Rolling ii. Forging iii. Extrusion iv. Wire Drawing v. Sheet Metal Forming 2. Based on Temperature of Working i. Hot Working ii. Cold Working iii. Warm Working 3. Based on the applied stress i. Direct Compressive Stress ii. Indirect Compressive Stress iii. Tensile Stress iv. Bending Stress v. Shear Stress Classification of Metal Working based on temperature. Hot working: It is defined as the mechanical working of metal at an elevated (higher) temperature above a particular temperature. This temperature is referred to RCT(Re Crystallization Temperature). Cold Working: It is defined as the mechanical working of metal below RCT. Warm Working: It is defined as the mechanical working of metal at a temperature between that of Hot working and Cold Working. Ingot is the starting raw metal for all metal working process. Molten metal from the furnace is taken and poured into metallic moulds and allowed to cool or solidify. The cooled solid metal mass is then taken out of the mould. This solid metal is referred to as Ingot.This Ingot is later on converted to other forms by mechanical working. -

Creusot Steam Hammer

CREUSOT STEAM HAMMER An International Historic Mechanical Engineering Landmark The American Society of Mechanical Engineers • September 16, 1981 Le Creusot, France Elsewhere in Le Creusot stands another monument, THE CREUSOT a statue of Eugene Schneider (1805-1875), STEAM HAMMER patriarch of the family that ruled the ironworks and Birth of a Giant much of the region Few engineering “firsts” are as clouded in controversy as the for 150 years. steam forging hammer. The international intrigue, the testimonies citing immaculate conception, and the accusations of piracy that have contested the birth of this singular technology will not be laid to rest with the dedication of this landmark. The towering Creusot hammer may be considered symbolic not only of the achieve- ments of the Creusot ironworks, but of the multi-national origins of the concept of the steam hammer, with credit spread among such French engineers as François Cavé, Eugène Schneider, and François Bourdon, and British engineers James Nasmyth, William Deverell, and James Watt. All appreciated the need for a steam-powered tool able to shape, strengthen, and hammer out impurities from iron objects that Ailleurs dans le Creusot, required forging. The capacities of existing water-powered trip, un autre monument, tilt, and lift hammers early in the nineteenth century were increas- la statue d’Eugène ingly found wanting in responding to the demands of manufactur- Schneider (1805-1875) ing many new classes of heavy machinery. Both the problem and partiarche régnant sur the solution grew more obvious as steam engines multiplied in l’usine et la plus grande partie de la région number, size, and power, their designs requiring ever-larger, il y a 150 ans. -

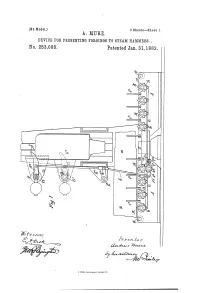

DEVICE for PRESENTING FORGINGS to STEAM HAMMERS, No

(No Model.) 3 Sheets-Sheet 1. A. MURE. DEVICE FOR PRESENTING FORGINGS TO STEAM HAMMERS, No. 253,088, Patented Jan. 31, 1882. N. PETERS. Fhcio.tithographer, Washington, D. C. (No Model.) 3. Sheets-Sheet 2. A, MURE, DEWICE FOR PRESENTING FORGINGS TO STEAM HAMMERS, No. 253,088, Patented Jan. 31, 1882, 1. L- al is sees - - - - - - - ----s - His 7% a zerrer N. peers, Photolithographer, Washington, D.C. (No Model.) 3 Sheets-Sheet 3. A, MURE, DEVICE FOR PRESENTING FORGINGS TO STEAM HAMMERS. No. 253,088, Patented Jan. 31, 1882, | 772 (z 6 de - Zzz z-e 2 z zo. 2 C4-ace (2a2zed 24-ce/ze y Are 4; 4. UNITED STATES PATENT OFFICE. ANDREW MURE, OF GLASGOW, COUNTY OF LANARK, SCOTLAND. DEVICE FOR PRESENTING FORGINGS TO STEAM - HAMMERS. SPECIFICATION forming part of Letters Patent No. 253,088, dated January 31, 1882. Application filed December 10, 1881. (No model.) Patented in England August 4, 1881. To all chon it may concern: engage the one or the other of its ends with Be it known that I, ANDREWMURE, of Glas the teeth of the wheel c, or to place it in a gow, in the county of Lanark, North Britain, neutral position. A spring catch-piece, f', have invented Improvements in Moving or formed with three V-notches, bears upon the 55 Traversing and Holding Forgings or Ingots un back of the pawlf, and upon the said back of der Steam-Hammers, or equivalent hammering the pawl is a corresponding projection to take apparatus, and in the means employed there into one or other of these V-notches in accord for, (for which I have received Letters Patent ance with the position which the pawl fis to of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and take. -

ANSI/ASME B31.1, "Power Piping" American National Standard

INDD B31.1 92 m 2595512 0078031 7T0 M ASME-B31.1 ADOPTION NOTICE ASME-B31.1, "Piping, Power," was adopted on October 3, 1994 for use by the Department of Defense (DoD). Proposed changes by DoD activities must be submitted to the DoD Adopting Activity: Commanding Officer, Naval Construction Battalion Center, Code 156, 1000 23rd Avenue, Port Hueneme, CA 93043-4301. DoD activities may obtain copies of this standard from the Standardization Document Order Desk, 700 Robbins Avenue, Building 4D, Philadelphia, PA 19111-5094. The private sector and other Government agencies may purchase copies from the American Society of Mechanical Engineers, 345 East 47th Street, New York, NY 10017. Custodians: Adopting Activity Army - ME Navy - YD-1 Navy - YD-1 Air Force - 99 FSC 4710 DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A. Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. COPYRIGXT American Society of Mechanical Engineers Lfensed by Information7Handling Services M1Il fill I 1 I I I tc)!@SI The American Society of Mechanical Engineers A N A M E R I C A N N A T I O N A L S T A N D A R D ASME CODE FOR PRESSURE PIPING, B31 ASME B31.1-2001 (Revision of ASME B31.1-1998) Rc~w5od By GLOBAL ENGEGDOCUMh COPYRIGHT American Society of ecchanical Engineers e UAPsfASt Licensed by Information Handling Services Date of Issuance: December 10, 2001 Mandatory Date: June 10, 2002 7his Edition was approved by the American National Standards Institute and designated ASME B31.1-2001 on July 2, 2001 The 2001 Edition of this Code is being issued with an automatic update service that includes Addenda, Interpretations, and Cases.