The Death Flight of Larry Mcdonald

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Congress - New Members” of the Robert T

The original documents are located in Box 10, folder “Congress - New Members” of the Robert T. Hartmann Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Gerald Ford donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Some items in this folder were not digitized because it contains copyrighted materials. Please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library for access to these materials. Digitized from Box 10 of the Robert T. Hartmann Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library .., SENATE I RepuL~ans · Garn, E. J. Utah Laxalt, Paul Nevada Democrats Bumpers, Dale Arkansas Culver, John C. Iowa Ford, Wendell Kentucky Glenn, John H. Ohio Hart, Gary W. Colorado Leahy, Patrick J. Vermont Morgan, Robert B. North Carolina Stone, Richard Florida The New Hampshire race has not been decided. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES (REPUBLICANS) David F. Emery Maine Millicent Fenwick New Jersey William F. Goodling Pennsylvania Bill Gradison Ohio Charles E. Grassley Iowa Tom Hagedorn Minnesota George V. Hansen Idaho . Henry J. Hyde Illinois James M. -

Voter Betrayal! by Tom Gow

www.freedomfirstsociety.org August 2010 Voter Betrayal! by Tom Gow [T]he two parties should be almost is widespread and deep enough, a were elected to the House of identical, so that the American “revolution” of sorts occurs, and the Representatives. Unfortunately, these people can “throw the rascals out” party controlling Congress changes. freshmen quickly discovered that at any election without leading to Such a “revolution” occurred in keeping on course was not as easy as any profound or extensive shifts 1994 with the election of the 104th they had imagined. in policy. Congress. But Establishment Insiders In fact, before they even got to — [Establishment Insider] were too clever for angry, uninformed Washington most had allowed Carroll Quigley voters, and they made sure that the themselves to be tied by Establishment Tragedy and Hope (1966) “revolution” was in form only. In “conservative” and internationalist 2010, history threatens to repeat itself, Newt Gingrich to a flawed and even Periodically, voters become angry so let’s see what we can learn from dangerous “Contract with America.” over too much government coming history. Moreover, when the new unschooled from Washington. Many then support congressmen arrived in Washington, congressional candidates who promise A Lesson From History they found themselves outgunned they will work to bring Washington In 1994, a number of naive, but well by the more experienced staff of under control. If voter discontent intentioned Republican candidates established veterans. Long hours and Wikimedia: Scrumshus Freedom First Society What’s Missing congressman is supposed to go back The reason voters are consistently to Washington and work to achieve the disappointed when they send a “good” best deal possible for his constituents representative to Washington to or for the nation. -

Coddling, Fraternization, and Total War in Camp Crossville, Tennessee

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 5-2004 Making the Most of a Bad Situation: Coddling, Fraternization, and Total War in Camp Crossville, Tennessee Gregory J. Kupsky University of Tennessee, Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Kupsky, Gregory J., "Making the Most of a Bad Situation: Coddling, Fraternization, and Total War in Camp Crossville, Tennessee. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2004. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/4636 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Gregory J. Kupsky entitled "Making the Most of a Bad Situation: Coddling, Fraternization, and Total War in Camp Crossville, Tennessee." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in History. G. Kurt Piehler, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: George White, Vejas Liulevicius Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Gregory J. -

The Kentucky High School Athlete, January 1964 Kentucky High School Athletic Association

Eastern Kentucky University Encompass The Athlete Kentucky High School Athletic Association 1-1-1964 The Kentucky High School Athlete, January 1964 Kentucky High School Athletic Association Follow this and additional works at: http://encompass.eku.edu/athlete Recommended Citation Kentucky High School Athletic Association, "The Kentucky High School Athlete, January 1964" (1964). The Athlete. Book 97. http://encompass.eku.edu/athlete/97 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Kentucky High School Athletic Association at Encompass. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Athlete by an authorized administrator of Encompass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HiqhkhoolAthMe CLASS A STATE CHAMPION LYNCH EAST MAIN r.*24'f '10' \ .^. > > *'''*^ '^ * "» s =^'^«ii i® '^^ -^ .^ I ^ ! > Imi1 *^ \ fs»-i ^ \ isi/*- :ftr.?*"" rtt***®* «iKI»», (Left to Right) Front Row: Julius Hodges, Vern Jacltson, Lowell Flanary, Truman McGeorge, Rick Hagy, Gary Lewis, Lynn Pippin, Glenn Wood, Ron Graham, Dan Russell, Coach Ed Miracle. Second Row: Coach Morgan, Ray Zlamal, E. Amos, A. Garner, Joe Hall, P. Peeples, W. Freeman, Paul Hightower, Jr., Ron Johnson, J. French. Third Row: Coach Staley. John CaroU, Jim Estep, John Palko, L. Cornett, Mike O'BradoYich, Gerry Roberts, Wayne Robinson, D. Cuzzart, Dub Potter. Fourth Row: Coach Scott, Ben Thomas, R. Brown, John Crum, M. Snow, J. Hawkins, A. Gaines. Fifth Row: Ulis Price, Ed Massey, Ben Massey, Will Anderson, Len Clark, Frank King, W. C. Jordan. Sixth Row: Earl Smith, -

HON. LARRY Mcdonald HOUSE of REPRESENTATIVES-Tuesday

4150 CO.NGKbSMONAL RECORD - HOUSE February 25, 1975 would be even during a period of unemploy THE DRAMATIC DECLINE IN U.S. "peace," the Soviet Union pursues only a ment. NAVAL STRENGTH rhetorical "detente" while pushing ahead in It is not the market economy (or "the (By Allan C. Brownfeld) all major weapons systems and armaments. capitalist system") which is responsible for WASHINGTON.-Wbile liberals in Washing Our deteriorating defense position is the this calamity but our own mistaken mone ton tell us that we are spending too much responsibility of both parties--of the Demo tary and financial policy. What we have done money for national defense, and conserva crats who say that, despite Soviet superiority, is to represent on a colossal scale what in tives assure us that under the current Re we spend "too much" on defense-and Re the past produced the recurring cycles of publican administration we have maintained publicans who assure us that, despite dra booms and depressions; to allow a long in• our national strength, the facts tell a far matic Soviet advances we are still "number fl-ationary boom to bring about a misdirec different--and far more depressing story. one." tion of labor and other resources into em Part of this story is described in some de The U.S. Navy has been cut almost in ployments in which they can be maintained tail in the 1974-75 edition of Jane's Fight half within the past six years. In addition, only so long as inflation exceeds expectations. ing Ships, the Brttish annual which has long states Captain Moore, the U.S. -

Treaty Termination and the Separation of Powers: the Constitutional Controversy Continues in Goldwater V

Denver Journal of International Law & Policy Volume 9 Number 2 Summer Article 6 May 2020 Treaty Termination and the Separation of Powers: The Constitutional Controversy Continues in Goldwater v. Carter, 100 S. Ct. 533 (1979) (Mem.) David A. Gottenborg Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/djilp Recommended Citation David A. Gottenborg, Treaty Termination and the Separation of Powers: The Constitutional Controversy Continues in Goldwater v. Carter, 100 S. Ct. 533 (1979) (Mem.), 9 Denv. J. Int'l L. & Pol'y 239 (1980). This Case Notes is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Denver Sturm College of Law at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Denver Journal of International Law & Policy by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],dig- [email protected]. CASE NOTE Treaty Termination and the Separation of Powers: The Constitutional Controversy Continues in Goldwater v. Carter, 100 S. Ct. 533 (1979) (Mem.) DAVID A. GOTrENBORG* I. INTRODUCTION Although the United States Constitution expressly provides how the President may make treaties,1 it is completely silent as to the process by which treaties should be terminated. In Goldwater v. Carter,2 a number of members of Congress sought to have the constitutional question re- garding the proper procedures required for the termination of treaties ju- dicially resolved.3 The suit was filed in response to President Carter's an- nouncement 4 that he was terminating the Mutual Defense Treaty of 1954 with the Republic of China.' Therefore, while the narrower issue was whether the President could unilaterally terminate the Mutual Defense Treaty without first consulting the Congress, the entire separation of powers question as to the extent of permissible congressional involvement in treaty terminations was opened for judicial review. -

EXTENSIONS of REMARKS HON. LARRY Mcdonald

15958 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS July 15, 1981 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS WHICH DIRECTION-THE Now, just between ourselves (laughter), do cratic" and scratch out the word "Socialist" DEMOCRATIC PARTY?-II you know any administrative officer that and let the two platforms lay there, and then ever tried to stop Congress from appropriat study the record of the present administra ing money? Do you think there has been tion up to date. HON. LARRY McDONALD any desire on the part of Congress to curtail Af~er you have done that, make your OF GEORGIA appropriations? mind up to pick up the platform that more IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Why, not at all. The fact is, that Congress nearly squares with the record and you will is throwing them right amd left, don't even have your hand on the Socialist platform; Wednesday, July 15, 1981 tell what they are for. <Laughter.) you would not dare touch the Democratic e Mr. McDONALD. Mr. Speaker, yes As to the subsidy-never at any time in platform. terday I shared with my colleague and the history of this or any other country And incidentally, let me say that it is not were there so many subsidies granted to pri the first time in recorded history that a the American people, part I of Alfred vate groups and on such a large scale. E. Smith's remarks to the Liberty group of men have stolen the livery of the And the truth is that every administrative church to do the work of the devil. League dinner here in Washington, officer sought to get all he possibly could, to D.C., over 45 years ago in January of expand the activities of his own office, and If you study this whole situation you will throw the money of the people right and find that is at the bottom of all our trou 1936. -

Congress - 94Th Session (1)” of the Loen and Leppert Files at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 5, folder “Congress - 94th Session (1)” of the Loen and Leppert Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Gerald Ford donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Some items in this folder were not digitized because it contains copyrighted materials. Please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library for access to these materials. 94th CONGRESS 1? -New- GOP Members (Hot!~-~) i (1) ... DAVID F. EMERY Maine 25 yrs. old; single Moderate to conservative (2) MILLICENT FENWICK N. J. 64 yrs. old; married Liberal, pipe smoker· (3) WILLIAM F. GOODLING Pa. 46 yr s. old; married Should be conservative (4) BILL GRADIS ON Ohio 45 yrs. old Conservative to moderate (5) CHARLES E. GRASSLEY Iowa 41 yrs. old; married Conservative (6) TOM HAGEDORN Minn. 30 yrs. old; married; farmer Ultra -conservative (7) GEORGE V. HANSEN Idaho 44 yrs. old; married Ultra -conservative (8) HENRY J. HYDE Ill. 50 yrs. old; married Conservative (9) JAMES M. JEFFORDS Vt. -

LAWRENCE PATTON Mcdonald (19 35-I983)

AMERICAN OPINION Essay on Character: LAWRENCE PATTON McDONALD (19 35-i983) he following is based on whe n a ll men dou bt yo u ," extensive first -person in hauntingly appropriate. T terviews with Congress "But the mourners who as man Lawrence Patton Me sembled at Constitution Hall to Donald's family, friends, and honor McDonald were never congress ional staff, and on first among his doubters," Mr. Dart hand interviews by the author wrote. "[His doubtersI were lib with the Georgia Democrat dur eral s who dismissed his arch ing his nin e years in Congress. conservative and anti-Commu Origina lly intended as an ap nist views as anachro nisms pendix to the book, Day of the from the Cold War . The mour Cobra, the essay was omitted ners came as America's conser from the Thomas Nelson work vative phalanx, 3,700 strong , because of its length . It is pre filling the historic hall on a hot sented here on the occasion of the autumn afternoon to remember second anniversary of the KAL one of their own. To this gath 007 mid-air mas sacre and offers ering, Larry McDonald , the an assessment of the forces and Georgia congressman who was influences that -shaped Con ----- killed along with 268 other per gressman McDonald's chara cter sons on a Korean jetliner, has and career. already become a martyr." Because La w rence Patt on Mr. Dart did not know that the reading of Kipling's "If' was McDonald was the first elected a commentary on Congress man official in American history to be murdered by a foreign power - one he he came to hold his views can only be McDonald's character and chi ldhood. -

Commander Larry Mcdonald

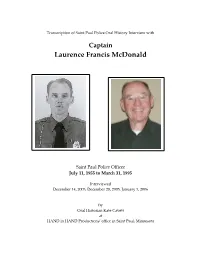

Transcription of Saint Paul Police Oral History Interview with Captain Laurence Francis McDonald Saint Paul Police Officer July 11, 1955 to March 31, 1995 Interviewed December 14, 2005, December 28, 2005, January 5, 2006 By Oral Historian Kate Cavett at HAND in HAND Productions’ office in Saint Paul, Minnesota This project was financed by: a grant from the State of Minnesota through the Minnesota Historical Society’s Grants-in-aid program a grant from the City of Saint Paul Star Grant Program Kate Cavett All photographs are from Commander McDonald’s personal photo collection or from the Saint Paul Police Department’s personnel files. © Saint Paul Police Department and HAND in HAND Productions 2006 Saint Paul Police Department Oral History Project 2 © HAND in HAND Productions and SPPD 2006 ORAL HISTORY Oral History is the spoken word in print. Oral histories are personal memories shared from the perspective of the narrator. By means of recorded interviews oral history documents collect spoken memories and personal commentaries of historical significance. These interviews are transcribed verbatim and minimally edited for accessibility. Greatest appreciation is gained when one can read an oral history aloud. Oral histories do not follow the standard language usage of the written word. Transcribed interviews are not edited to meet traditional writing standards; they are edited only for clarity and understanding. The hope of oral history is to capture the flavor of the narrator’s speech and convey the narrator’s feelings through the tenor and tempo of speech patterns. An oral history is more than a family tree with names of ancestors and their birth and death dates. -

The Kentucky High School Athlete, January 1969 Kentucky High School Athletic Association

Eastern Kentucky University Encompass The Athlete Kentucky High School Athletic Association 1-1-1969 The Kentucky High School Athlete, January 1969 Kentucky High School Athletic Association Follow this and additional works at: http://encompass.eku.edu/athlete Recommended Citation Kentucky High School Athletic Association, "The Kentucky High School Athlete, January 1969" (1969). The Athlete. Book 147. http://encompass.eku.edu/athlete/147 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Kentucky High School Athletic Association at Encompass. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Athlete by an authorized administrator of Encompass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HiqhkhoolAniMe CLASS A STATE CHAMPION LYNCH (Left to Right) Front Row: Tom Johnson, Roger Wilhoit, James Vicini, David Hollings- worth, Bobby Joe Golden, Mike Kirby, Joe Washington, Maceo Peeples, Terry Rodgers, Ron- nie Hampton, Ass't Coach Richard Smithson. Second Row: Ass't Coach Enoch Foutch, Ass't Coach Ray Jenkins, Ass't Coach John Staley, Danny Powell, Randy Adams, Millard Caldwell, Dennis Clark, Alan Wagers, David Sizemore, Mike Price, Charles Russell, Kenny Vicini, Thomas Roscoe, Darryl Washington, Gary Dye, Ass't Coach John Morgan, Coach Ed Miracle, Third Row: John Reasor, Roger Gibbons, Curtis Stewart, Ezell Smith, Mark Moran, Joe Gibson, Dwain Morrow, Ralph Price, Henry Rodgers, Tom Sheback, Jesse Mackey, Darryl Atkinson, Johnny Owens, Marc Merritt, Gary Standridge. Lynch 14-Old Ky. Home Lynch 19-Evarts 31 Lynch 25-Middlesboro -

1775 Water Place Marietta, Georgia 30339

1775 WATER PLACE MARIETTA, GEORGIA 30339 PROPERTY OVERVIEW The property is located at 1775 Water Place, Marietta, GA and is located in Cobb county. It has excellent access to Cobb Parkway, I-75 and I-285. Prior to be converted to a church, the property was originally used as a health club. The building totals approximately 141,170 SF with 47,991 SF on the upper level, 78,807 SF on the main level and 14,372 SF on the lower level. Approximately 67,000 SF of the total square footage is finished with the remaining square footage unfinished. In the finished area, there is a worship center as well as a chapel that each seat approximately 500-550 people. There are a number of classrooms of various sizes, a youth room, a large teen room, bookstore, multiple offices and a wellness center with showers, lockers and other amenities. PROPERTY FEATURES PRICING: $5,500,000 SF: 141,170+ Total SF (64,000+ finished SF) ACRES: 12.375 ± AC OI, Office Institutional District by the ZONING: City of Marietta PARKING: 272+ Spaces Water/Sewer by the city of Marietta and UTILITIES: Electricity by Georgia Power 1975, with partial renovations in 2004 YEAR BUILT: and 2008 FRONTAGE: Water Place and The Exchange Although all information is furnished regarding for sale, rental or financing is from sources we deem reliable, such information has not been verified and no express representation is made nor is any to be implied as to the accuracy thereof, and it is submitted subject to errors, omissions, changes of price, rental or other conditions, prior sale, lease or financing, or withdrawal without notice.