Chapter - Viii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Civil Society in Uncivil Places: Soft State and Regime Change in Nepal

48 About this Issue Recent Series Publications: Policy Studies 48 Policy Studies Policy This monograph analyzes the role of civil Policy Studies 47 society in the massive political mobilization Supporting Peace in Aceh: Development and upheavals of 2006 in Nepal that swept Agencies and International Involvement away King Gyanendra’s direct rule and dra- Patrick Barron, World Bank Indonesia matically altered the structure and character Adam Burke, London University of the Nepali state and politics. Although the opposition had become successful due to a Policy Studies 46 strategic alliance between the seven parlia- Peace Accords in Northeast India: mentary parties and the Maoist rebels, civil Journey over Milestones Places in Uncivil Society Civil society was catapulted into prominence dur- Swarna Rajagopalan, Political Analyst, ing the historic protests as a result of nation- Chennai, India al and international activities in opposition to the king’s government. This process offers Policy Studies 45 new insights into the role of civil society in The Karen Revolution in Burma: Civil Society in the developing world. Diverse Voices, Uncertain Ends By focusing on the momentous events of Ardeth Maung Thawnghmung, University of the nineteen-day general strike from April Massachusetts, Lowell 6–24, 2006, that brought down the 400- Uncivil Places: year-old Nepali royal dynasty, the study high- Policy Studies 44 lights the implications of civil society action Economy of the Conflict Region within the larger political arena involving con- in Sri Lanka: From Embargo to Repression ventional actors such as political parties, trade Soft State and Regime Muttukrishna Sarvananthan, Point Pedro unions, armed rebels, and foreign actors. -

Nepal-Legal Education-Seminar Report-1993-Eng

t n m v s T L a r ? < j_ L eg a l E ducation In N epal Three Day, National Seminar (December 24 - 26,1992) Seminar Proceedings Report Published by : International Commission of Jurists Nepal Section Ramshah Path, P. O. Box : 4659 Kathmandu, Nepal (In Co-operation with International Commission of Jurists (ICJ) / Geneva) International Commission of Jurists Nepal Section Executive Council Mr. Madhu Prasad Sharma Chairman Mr. Moti Kazi Sthapit Vice-chairman Mr. Kusum Shrestha Secretary General Mr. Anup Raj Sharma Treasurer Mr. Krishna Prasad Pant Member Mrs. Silu Singh Member Mr. Daman Dhungana Member Mr. Mahadev Yadav Member Ms. Indira Rana Member M anager Krishna Man Pradhan L e g a l E ducation In N e p a l Three Day National Seminar (December 24 - 26,1992) Seminar Proceedings Report Published by : International Commission of Jurists Nepal Section Ramshah Path, P. O. Box : 4659 Kathmandu, Nepal (In Co-operation with International Commission of Jurists (ICJ) / Geneva) ACKN O WLED G EM ENT This present publication is the outcome of a three day National Seminar on Legal Education In Nepal held on Dec 24-26, 1992 in Kathmandu and organized by ICJ/Nepal Section in collaboration with ICJ/Geneva, Switzerland. I believe the seminar proved to be a successful forum for law teachers, law researchers, lawyers, education planners to come together and discuss issues, problems and priorities in elevating the standards of legal education in the country. Some 245 participants both from the valley and outside representing law campuses, legal profession, judiciary, government agencies contributed meaningfully to the seminar deliberations. -

Samaj Laghubitta Bittiya Sanstha Ltd. Demat Shareholder List S.N

SAMAJ LAGHUBITTA BITTIYA SANSTHA LTD. DEMAT SHAREHOLDER LIST S.N. BOID Name Father Name Grandfather Name Total Kitta Signature 1 1301010000002317 SHYAM KRISHNA NAPIT BHUYU LAL NAPIT BHU LAL NAPIT / LAXMI SHAKYA NAPIT 10 2 1301010000004732 TIKA BAHADUR SANJEL LILA NATHA SANJEL DUKU PD SANJEL / BIMALA SANJEL 10 3 1301010000006058 BINDU POKHAREL WASTI MOHAN POKHAREL PURUSOTTAM POKHAREL/YADAB PRASAD WASTI 10 4 1301010000006818 REJIKA SHAKYA DAMODAR SHAKYA CHANDRA BAHADUR SHAKYA 10 5 1301010000006856 NIRMALA SHRESTHA KHADGA BAHADUR SHRESTHA LAL BAHADUR SHRESTHA 10 6 1301010000007300 SARSWATI SHRESTHA DHUNDI BHAKTA RAJLAWAT HARI PRASAD RAJLAWAT/SAROJ SHRESTHA 10 7 1301010000010476 GITA UPADHAYA SHOVA KANTA GNAWALI NANDA RAM GNAWALI 10 8 1301010000011636 SHUBHASINNI DONGOL SURYAMAN CHAKRADHAR SABIN DONGOL/RUDRAMAN CHAKRADHAR 10 9 1301010000011898 HARI PRASAD ADHIKARI JANAKI DATTA ADHIKARI SOBITA ADHIKARI/SHREELAL ADHIKARI 10 10 1301010000014850 BISHAL CHANDRA GAUTAM ISHWAR CHANDRA GAUTAM SAMJHANA GAUTAM/ GOVINDA CHANDRA GAUTAM 10 11 1301010000018120 KOPILA DHUNGANA GHIMIRE LILAM BAHADUR DHUNGANA BADRI KUMAR GHIMIRE/ JAGAT BAHADUR DHUNGANA10 12 1301010000019274 PUNESHWORI CHAU PRADHAN RAM KRISHNA CHAU PRADHAN JAYA JANMA NAKARMI 10 13 1301010000020431 SARASWATI THAPA CHITRA BAHADUR THAPA BIRKHA BAHADUR THAPA 10 14 1301010000022650 RAJMAN SHRESTHA LAXMI RAJ SHRESTHA RINA SHRESTHA/ DHARMA RAJ SHRESTHA 10 15 1301010000022967 USHA PANDEY BHAWANI PANDEY SHYAM PRASAD PANDEY 10 16 1301010000023956 JANUKA ADHIKARI DEVI PRASAD NEPAL SUDARSHANA ADHIKARI -

A Study on Nepali Modernity in the First Half of Twentieth Century A

Pathak 1 Tribhuvan University Modernist Imagination in Nepal: A Study on Nepali Modernity in the First Half of Deepak Kumar Deepak Pathak 2017 Twentieth Century A thesis submitted to the Central Department of English for the partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Philosophy in English odernity in theCentury First in odernity Half – Twentieth of By Deepak Kumar Pathak Central Department of English Kirtipur, Kathmandu April 2017 Modernist Imagination in Nepal: Nepali A Study on M Pathak 2 Tribhuvan University Central Department of English Letter of Recommendation This is to certify that Mr. Deepak Kumar Pathak has completed this thesis entitled "Modernist Imagination in Nepal: A Study on Nepali Modernity in the First Half of 20th Century" under my supervision. He has prepared this thesis for the partial fulfillment of the requirement for the Master of Philosophy in Arts (English) from Tribhuvan University. I recommend this for viva voce. ____________________ Dr. Abhi Narayan Subedi, Professor Central Department of English Tribhuvan University Kathmandu, Nepal Pathak 3 Tribhuvan University Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Letter of Approval This thesis titled "Modernist Imagination in Nepal: A Study on Nepali Modernity in the First Half of Twentieth Century" submitted to the Central Department of English, Tribhuvan University, Mr. Deepak Kumar Pathak has been approved by undersigned members of the research committee. Members of Research Committee: Internal Examiner ____________________ Dr. Abhi Narayan Subedi, Professor External Examiner ____________________ Dr. Ananda Sharma, Professor Head of Department Central Department of English, TU ____________________ Dr. Ammaraj Joshi, Professor Pathak 4 Acknowledgements I would like to express my heartfelt gratitude to my Guru and supervisor Professor Dr. -

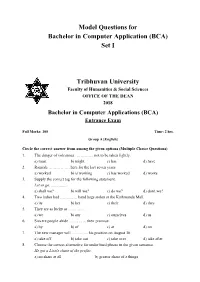

Model Questions for Bachelor in Computer Application (BCA) Set I

Model Questions for Bachelor in Computer Application (BCA) Set I Tribhuvan University Faculty of Humanities & Social Sciences OFFICE OF THE DEAN 2018 Bachelor in Computer Applications (BCA) Entrance Exam Full Marks: 100 Time: 2 hrs. Group A [English] Circle the correct answer from among the given options (Multiple Choice Questions) 1. The danger of volcanoes ………….. not to be taken lightly. a) must b) might c) has d) have 2. Ramesh ……………. here for the last seven years. a) worked b) is working c) has worked d) works 3. Supply the correct tag for the following statement. Let us go, ………….. a) shall we? b) will we? c) do we? d) don't we? 4. Two ladies had …………. hand bags stolen at the Kathmandu Mall. a) its b) her c) their d) they 5. They are as lucky as …………. a) we b) our c) ourselves d) us 6. Sincere people abide …………. their promise. a) by b) of c) at d) on 7. The new manager will ………… his position on August 30. a) take off b) take out c) take over d) take after 8. Choose the correct alternative for underlined phrase in the given sentence. He got a Lion's share of the profits. a) no share at all b) greater share of a things c) very small part d) little profit 9. There is someone in the room ………….. I certainly heard a great noise. a) and b) but c) for d) so 10. Neither of them ………… a problem. a) anticipate b) anticipates c) have anticipated d) are anticipating 11. Choose the correct passive voice for the following sentence. -

Language Politics and State Policy in Nepal: a Newar Perspective

Language Politics and State Policy in Nepal: A Newar Perspective A Dissertation Submitted to the University of Tsukuba In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in International Public Policy Suwarn VAJRACHARYA 2014 To my mother, who taught me the value in a mother tongue and my father, who shared the virtue of empathy. ii Map-1: Original Nepal (Constituted of 12 districts) and Present Nepal iii Map-2: Nepal Mandala (Original Nepal demarcated by Mandalas) iv Map-3: Gorkha Nepal Expansion (1795-1816) v Map-4: Present Nepal by Ecological Zones (Mountain, Hill and Tarai zones) vi Map-5: Nepal by Language Families vii TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents viii List of Maps and Tables xiv Acknowledgements xv Acronyms and Abbreviations xix INTRODUCTION Research Objectives 1 Research Background 2 Research Questions 5 Research Methodology 5 Significance of the Study 6 Organization of Study 7 PART I NATIONALISM AND LANGUAGE POLITICS: VICTIMS OF HISTORY 10 CHAPTER ONE NEPAL: A REFLECTION OF UNITY IN DIVERSITY 1.1. Topography: A Unique Variety 11 1.2. Cultural Pluralism 13 1.3. Religiousness of People and the State 16 1.4. Linguistic Reality, ‘Official’ and ‘National’ Languages 17 CHAPTER TWO THE NEWAR: AN ACCOUNT OF AUTHORS & VICTIMS OF THEIR HISTORY 2.1. The Newar as Authors of their history 24 2.1.1. Definition of Nepal and Newar 25 2.1.2. Nepal Mandala and Nepal 27 Territory of Nepal Mandala 28 viii 2.1.3. The Newar as a Nation: Conglomeration of Diverse People 29 2.1.4. -

Cultural Capital and Entrepreneurship in Nepal: the Readymade Garment Industry As a Case Study

Cultural Capital and Entrepreneurship in Nepal: The Readymade Garment Industry as a Case Study Mallika Shakya Development Studies Institute (DESTIN) February 2008 Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by the University of London UMI Number: U613401 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U613401 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 O^lJbraryofPeMic. find Economic Science Abstract This thesis is an ethnographic account of the modem readymade garment industry in Nepal which is at the forefront of Nepal’s modernisation and entry into the global trade system. This industry was established in Nepal in 1974 when the United States imposed country-specific quotas on more advanced countries and flourished with Nepal’s embrace of economic liberalisation in the 1990s. Post 2000 however, it faced two severe crises: the looming 2004 expiration of the US quota regime which would end the preferential treatment of Nepalese garments in international trade; and the local Maoist insurgency imposed serious labour and supply chain hurdles to its operations. -

The Abolition of Monarchy and Constitution Making in Nepal

THE KING VERSUS THE PEOPLE(BHANDARI) Article THE KING VERSUS THE PEOPLE: THE ABOLITION OF MONARCHY AND CONSTITUTION MAKING IN NEPAL Surendra BHANDARI Abstract The abolition of the institution of monarchy on May 28, 2008 marks a turning point in the political and constitutional history of Nepal. This saga of constitutional development exemplifies the systemic conflict between people’s’ aspirations for democracy and kings’ ambitions for unlimited power. With the abolition of the monarchy, the process of making a new constitution for the Republic of Nepal has started under the auspices of the Constituent Assembly of Nepal. This paper primarily examines the reasons or causes behind the abolition of monarchy in Nepal. It analyzes the three main reasons for the abolition of monarchy. First, it argues that frequent slights and attacks to constitutionalism by the Nepalese kings had brought the institution of the monarchy to its end. The continuous failures of the early democratic government and the Supreme Court of Nepal in bringing the monarchy within the constitutional framework emphatically weakened the fledgling democracy, but these failures eventually became fatal to the monarchical institution itself. Second, it analyzes the indirect but crucial role of India in the abolition of monarchy. Third, it explains the ten-year-long Maoist insurgency and how the people’s movement culminated with its final blow to the monarchy. Furthermore, this paper also analyzes why the peace and constitution writing process has yet to take concrete shape or make significant process, despite the abolition of the monarchy. Finally, it concludes by recapitulating the main arguments of the paper. -

Annual Report (2016/17)

MINISTRY OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL ANNUAL REPORT (2016/17) KATHMANDU, NEPAL AUGUST 2017 Nepal: Facts and figures Geographical location: Latitude: 26° 22' North to 30° 27' North Longitude: 80° 04' East to 88° 12' East Area: 147,181 sq. km Border: North—People's Republic of China East, West and South — India Capital: Kathmandu Population: 28431494 (2016 Projected) Country Name: Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal Head of State: Rt. Honourable President Head of Government: Rt. Honourable Prime Minister National Day: 3 Ashwin (20 September) Official Language: Nepali Major Religions: Hinduism, Buddhism Literacy (5 years above): 65.9 % (Census, 2011) Life Expectancy at Birth: 66.6 years (Census, 2011) GDP Per Capita: US $ 853 (2015/16) Monetary Unit: 1 Nepalese Rupee (= 100 Paisa) Main Exports: Carpets, Garments, Leather Goods, Handicrafts, Grains (Source: Nepal in Figures 2016, Central Bureau of Statistics, Kathmandu) Contents Message from Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Foreign Affairs Foreword 1. Year Overview 1 2. Neighbouring Countries and South Asia 13 3. North East Asia, South East Asia, the Pacific and Oceania 31 4. Central Asia, West Asia and Africa 41 5. Europe and Americas 48 6. Regional Cooperation 67 7. Multilateral Affairs 76 8. Policy, Planning, Development Diplomacy 85 9. Administration and Management 92 10. Protocol Matters 93 11. Passport Services 96 12. Consular Services 99 Appendices I. Joint Statement Issued on the State Visit of Prime Minister of Nepal, Rt. Hon’ble Mr. Pushpa Kamal Dahal ‘Prachanda’ to India 100 II. Treaties/Agreements/ MoUs Signed/Ratified in 2016/2017 107 III. Nepali Ambassadors and Consuls General Appointed in 2016/17 111 IV. -

Layout Fisher 2011.Indd

The Mahesh Chandra Regmi Lecture 2011 Globalisation in Nepal Mahesh Chandra Regmi (1929-2003) Theory and Practice The Mahesh Chandra Regmi Lecture was instituted by the Social Science Baha in 2003 to acknowledge and honour historian Mahesh Chandra Regmi’s contribution to the social sciences in Nepal. The 2011 Mahesh Chandra Regmi Lecture was delivered by James F. Fisher. Prof Fisher was Professor of Anthropology and Asian Studies at Carleton College, Minnesota, where he taught for 38 years. His geographic interests lie in South Asia, and he has done fi eldwork in Nepal on and off for almost 50 years on economics and ecology among Magars in Dolpa, education and tourism among Sherpas near Mount Everest, and he wrote a person-centred James F. Fisher ethnography on Tanka Prasad Acharya, human rights activist and one-time prime minister of Nepal. As a visiting Fulbright Professor, he spent two years helping start a new Department of Sociology and Anthropology at Tribhuvan University, Nepal. Prof Fisher’s books include Living Martyrs: Individuals and evolution in Nepal (1997); Sherpas: Refl ections on Change in Himalayan Nepal (1990), Trans-Himalayan Traders: Economy, Society, and Culture in Northwest Nepal (1986); Himalayan Anthropology: the Indo-Tibetan Interface (1978); and Introductory Nepali (1965). 17 AUGUST 2011 SOCIAL SCIENCE BAHA 9 789937 842143 KATHMANDU, NEPAL The Mahesh Chandra Regmi Lecture 2011 Globalisation in Nepal Theory and Practice James F. Fisher GLOBALISATION IN NEPAL: THEORY AND PRACTICE i This is the full text of the Mahesh Chandra Lecture 2011 delivered by James F. Fisher on 17 August 2011, at The Shanker Hotel, Kathmandu, as part of the conference ‘Changing Dynamics of Nepali Society and Politics’ organised by the Social Science Baha with the Alliance for Social Dialogue and the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies. -

Nationalism and Regional Relations in Democratic Transitions: Comparing Nepal and Bhutan

Wright State University CORE Scholar Browse all Theses and Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2018 Nationalism and Regional Relations in Democratic Transitions: Comparing Nepal and Bhutan Deki Peldon Wright State University Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all Part of the International Relations Commons Repository Citation Peldon, Deki, "Nationalism and Regional Relations in Democratic Transitions: Comparing Nepal and Bhutan" (2018). Browse all Theses and Dissertations. 1981. https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all/1981 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Browse all Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NATIONALISM AND REGIONAL RELATIONS IN DEMOCRATIC TRANSITIONS: COMPARING NEPAL AND BHUTAN A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts By DEKI PELDON Bachelor of Arts, Asian University for Women, 2014 2018 Wright State University WRIGHT STATE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL [May 4, 2018] I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY DEKI PELDON ENTITLED NATIONALISM AND REGIONAL RELATIONS IN DEMOCRATIC TRANSITIONS: COMPARING NEPAL AND BHUTAN BE ACCEPTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS. Laura M. Luehrmann, Ph.D. Thesis Director Laura M. Luehrmann, Ph.D. Director, Master of Arts Program in International and Comparative Politics Committee on Final Examination: Laura M. Luehrmann, Ph.D. School of Public and International Affairs Pramod Kantha, Ph.D. School of Public and International Affairs Judson Murray, Ph.D. -

The Biography of a Magar Communist Anne De Sales

The Biography of a Magar Communist Anne de Sales To cite this version: Anne de Sales. The Biography of a Magar Communist. David Gellner. Varieties of Activist Ex- periences in South Asia, Sage, pp.18-45, 2010, Governance, Conflict, and Civic Action Series. hal- 00794601 HAL Id: hal-00794601 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00794601 Submitted on 10 Mar 2013 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Chapter 2 The Biography of a Magar Communist Anne de Sales Let us begin with the end of the story: Barman Budha Magar was elected a Member of Parliament in 1991, one year after the People’s Movement (jan andolan) that put an end to thirty years of the Partyless Panchayat ‘democracy’ in Nepal. He had stood for the Samyukta Jana Morcha or United People’s Front (UPF), the political wing of the revolutionary faction of the Communist Party of Nepal, or CPN (Unity Centre).1 To the surprise of the nation, the UPF won 9 seats and the status of third-largest party with more than 3 per cent of the national vote. However, following the directives of his party,2 Barman, despite being an MP, soon went underground until he retired from political life at the time of the People’s War in 1996.