A Study of the Role of Intellectuals in the 1931 Uprising

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Download

}vkuprpêsq|isqhuzrlnhênlvnyhmzrlnhêky|{}h hpqh jpwly lrzr|ypqlêsq|isqhuzrlnhênlvnyhmzrlnhêky|{}h VODNIKI LJUBLJANSKEGA GEOGRAFSKEGA DRUŠTVA Azija CIPER MONIKA BENKOVIČ KRAŠOVEC VODNIKI LJUBLJANSKEGA GEOGRAFSKEGA DRUŠTVA Azija CIPER Monika Benkovič Krašovec ©2007, Ljubljansko geografsko društvo, založba zRC Urednik: Drago Kladnik Recenzenta: Blaž Repe, Aleš Smrekar Korektor: Drago Kladnik Oblikovanje in likovno-grafična ureditev: Milojka Žalik Huzjan Prelom: Brane Vidmar Kartografija: Boštjan Rogelj Fotografije: Andrej Kranjc Izdajatelj: Ljubljansko geografsko društvo Za izdajatelja: Katja Vintar Mally Založnik: založba zRC, zRC SAzU Za založnika: Oto Luthar Glavni urednik: Vojislav Likar Tisk: Present d. o. o. Naklada: 300 Fotografija na ovitku: Stiskalnica za pridelavo oljčnega olja v središču Akrotirija. CIP - Kataložni zapis o publikaciji Narodna in univerzitetna knjižnica, Ljubljana 913(564.3)(036) 908(564.3) BENKOVIČ Krašovec, Monika Ciper / Monika Benkovič Krašovec ; [kartografija Boštjan Rogelj ; fotografije Andrej Kranjc]. - Ljubljana : založba zRC, zRC SAzU, 2007. - (Vodniki Ljubljanskega geografskega društva. Azija, ISSN 1408-6409 ; 4) ISBN 978-961-6568-93-7 231627264 Digitalna različica (pdf) je pod pogoji licence CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 prosto dostopna: https://doi.org/10.3986/9789616568937 UVOD TEMELJNI PODATKI zA REPUBLIKO CIPER: Uradno ime: Republika Ciper Državna ureditev: predsedniška republika Površina: 5896 km2 Število prebivalcev (2006): 784.300 Gostota poselitve (2006): 133 prebivalcev/km2 Nikozija (grško Levkosía; 219.000 -

Cypriot Greek As a Heritage and Community Language in London: (Socio)Linguistic Aspects of a Non-Standard Variety in a Diasporic Context1

CYPRIOT GREEK AS A HERITAGE AND COMMUNITY LANGUAGE IN LONDON: (SOCIO)LINGUISTIC ASPECTS OF A NON-STANDARD VARIETY IN A DIASPORIC CONTEXT1 Petros Karatsareas University of Westminster Abstract Cypriot Greek has been spoken in the United Kingdom as a heritage and community language for over a century by a sizeable Greek Cypriot diaspora. In this chapter, I describe Cypriot Greek as it is spoken in London, presenting some of its key linguistic characteristics and discussing aspects of its sociolinguistic status in the wider UK context. In terms of linguistic characteristics, I present older, regional features that are currently being levelled in Cyprus but which survive in London’s Cypriot Greek; Standard Modern Greek features that are increasingly used in London even in informal instances of communication; and, phenomena that are attributed to language contact with English. In terms of sociolinguistic status, I focus on the intergenerational transmission of Cypriot Greek in London and identify three key factors that threaten its maintenance in the diaspora: its minority status with respect to English, its non- prestigious status with respect to Standard Modern Greek, and also its non-prestigious status with respect to Cypriot Greek as it is currently spoken in Cyprus. 1. London’s Greek Cypriot diaspora: a tile in the city’s multicultural and multilingual mosaic The United Kingdom has historically been the principal destination of Cypriot emigrants (Constantinou, 1990). Christodoulou places the onset of migration from Cyprus to the UK in 1902 (1959; cited in Constantinou, 1990: 151– 152). Migration remained low until the mid-1950s and only began to increase in 1955–1959, when violence on the island intensified during the anti-colonial struggles. -

Monuments.Pdf

© 2017 INTERPARLIAMENTARY ASSEMBLY ON ORTHODOXY ISBN 978-960-560 -139 -3 Front cover page photo Sacred Monastery of Mount Sinai, Egypt Back cover page photo Saint Sophia’s Cathedral, Kiev, Ukrania Cover design Aristotelis Patrikarakos Book artwork Panagiotis Zevgolis, Graphic Designer, HELLENIC PARLIAMENT | Publications & Printing Directorate Editing George Parissis, HELLENIC PARLIAMENT | International Affairs Directorate Maria Bakali, I.A.O. Secretariat Lily Vardanyan, I.A.O. Secretariat Printing - Bookbinding HELLENIC PARLIAMENT | Publications & Printing Directorate Οι πληροφορίες των κειμένων παρέχονται από τους ίδιους τους διαγωνιζόμενους και όχι από άλλες πηγές The information of texts is provided by contestants themselves and not from other sources ΠΡΟΛΟΓΟΣ Η προστασία της παγκόσμιας πολιτιστικής κληρονομιάς, υποδηλώνει την υψηλή ευθύνη της κάθε κρατικής οντότητας προς τον πολιτισμό αλλά και ενδυναμώνει τα χαρακτηριστικά της έννοιας “πολίτης του κόσμου” σε κάθε σύγχρονο άνθρωπο. Η προστασία των θρησκευτικών μνημείων, υποδηλώνει επί πλέον σεβασμό στον Θεό, μετοχή στον ανθρώ - πινο πόνο και ενθάρρυνση της ανθρώπινης χαράς και ελπίδας. Μέσα σε κάθε θρησκευτικό μνημείο, περι - τοιχίζεται η ανθρώπινη οδύνη αιώνων, ο φόβος, η προσευχή και η παράκληση των πονεμένων και αδικημένων της ιστορίας του κόσμου αλλά και ο ύμνος, η ευχαριστία και η δοξολογία προς τον Δημιουργό. Σεβασμός προς το θρησκευτικό μνημείο, υποδηλώνει σεβασμό προς τα συσσωρευμένα από αιώνες αν - θρώπινα συναισθήματα. Βασισμένη σε αυτές τις απλές σκέψεις προχώρησε η Διεθνής Γραμματεία της Διακοινοβουλευτικής Συνέ - λευσης Ορθοδοξίας (Δ.Σ.Ο.) μετά από απόφαση της Γενικής της Συνέλευσης στην προκήρυξη του δεύτερου φωτογραφικού διαγωνισμού, με θέμα: « Καταστροφή των μνημείων της Χριστιανικής Ανατολής ». Επι πλέον, η βούληση της Δ.Σ.Ο., εστιάζεται στην πρόθεσή της να παρουσιάσει στο παγκόσμιο κοινό, τον πολιτισμικό αυτό θησαυρό της Χριστιανικής Ανατολής και να επισημάνει την ανάγκη μεγαλύτερης και ου - σιαστικότερης προστασίας του. -

Pdf | 371.17 Kb

450000 E 500000 E 550000 E 600000 E 650000 32o 30' 33o 00' 33o 30' 34o 00' 34o 30' Cape Andreas 395000 N 395000 N HQ UNFICYP MEDITERRANEAN SEA ﺍﻧﺘﺸﺎﺭ ﻗﻮﺓ ﺍﻷﻣﻢ ﺍﳌﺘﺤﺪﺓ ﳊﻔﻆ ﺍﻟﺴﻼﻡ ﰲ ﻗﱪﺹ Rizokarpaso 联塞部队部署 HQ UNPOL UNFICYP DEPLOYMENT FMPU Multinational Ayia Trias DÉPLOIEMENT DE L’UNFICYP Yialousa o o Vathylakas 35 30' 35 30' ДИСЛОКАЦИЯ ВСООНК MFR UNITED KINGDOM Sector 2 Leonarisso DESPLIEGUE DE L A UNFICYP HQ ARGENTINA Ephtakomi UNITED KINGDOM Galatia Cape Kormakiti SLOVAKIA Akanthou Komi Kebir UNPOL 500 m HQ Sector 1 Ardhana Karavas KYRENIA 500 m Kormakiti Lapithos Ayios Amvrosios Temblos Boghaz ARGENTINA / PARAGUAY / BRAZIL Dhiorios Myrtou 500 m Bellapais Trypimeni Trikomo ARGENTINA / CHILE 500 m 500 m Famagusta SECTOR 1 Lefkoniko Bay Sector 4 UNPOL VE WE K. Dhikomo Chatos WE XE HQ 390000 N UNPOL Kythrea 390000 N UNPOL VD WD ari WD XD Skylloura m Geunyeli Bey Keuy K. Monastir SLOVAKIA Mansoura Morphou am SLOVAKIA K. Pyrgos Morphou Philia Dhenia M Kaimakli Angastina Strovilia Post Kokkina Bay P. Zodhia LP 0 Prastio 90 Northing 9 Northing Selemant Limnitis Avlona UNPOL Pomos NICOSIA UNPOL 500 m Karavostasi Xeros UNPA Tymbou (Ercan) FAMAGUSTA UNPOL s s Cape Arnauti ti it a Akaki SECTOR 2 o Lefka r Kondea Kalopsidha Varosha Yialia Ambelikou n e o Arsos m m r a Khrysokhou a ro te rg Dherinia s t s Athienou SECTOR 4 e Bay is s ri SLOVAKIA t Linou A e P ( ) Mavroli rio P Athna Akhna 500 m u Marki Prodhromi Polis ko Evrykhou 500 m Klirou Troulli 1000 m S Louroujina UNPOL o o Pyla 35 00' 35 00' Kakopetria 500 mKochati Lymbia 1000 m DHEKELIA Ayia Napa Cape 500 m Pedhoulas SLOVAKIA S.B.A. -

The Gordian Knot: American and British Policy Concerning the Cyprus Issue: 1952-1974

THE GORDIAN KNOT: AMERICAN AND BRITISH POLICY CONCERNING THE CYPRUS ISSUE: 1952-1974 Michael M. Carver A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of The requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2006 Committee: Dr. Douglas J. Forsyth, Advisor Dr. Gary R. Hess ii ABSTRACT Douglas J. Forsyth, Advisor This study examines the role of both the United States and Great Britain during a series of crises that plagued Cyprus from the mid 1950s until the 1974 invasion by Turkey that led to the takeover of approximately one-third of the island and its partition. Initially an ancient Greek colony, Cyprus was conquered by the Ottoman Empire in the late 16th century, which allowed the native peoples to take part in the island’s governance. But the idea of Cyprus’ reunification with the Greek mainland, known as enosis, remained a significant tenet to most Greek-Cypriots. The movement to make enosis a reality gained strength following the island’s occupation in 1878 by Great Britain. Cyprus was integrated into the British imperialist agenda until the end of the Second World War when American and Soviet hegemony supplanted European colonialism. Beginning in 1955, Cyprus became a battleground between British officials and terrorists of the pro-enosis EOKA group until 1959 when the independence of Cyprus was negotiated between Britain and the governments of Greece and Turkey. The United States remained largely absent during this period, but during the 1960s and 1970s came to play an increasingly assertive role whenever intercommunal fighting between the Greek and Turkish-Cypriot populations threatened to spill over into Greece and Turkey, and endanger the southeastern flank of NATO. -

Page 1 GE.20-08066(E) Human Rights Council Forty-Third Session

United Nations A/HRC/43/G/41 General Assembly Distr.: General 18 June 2020 Original: English Human Rights Council Forty-third session 24 February–20 March 2020 Agenda item 2 Annual report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights and reports of the Office of the High Commissioner and the Secretary-General Note verbale dated 18 March 2020 from the Permanent Mission of Turkey to the United Nations Office at Geneva addressed to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights The Permanent Mission of the Republic of Turkey to the United Nations Office at Geneva and other international organizations in Switzerland presents its compliments to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, and has the honour to convey a copy of a letter by the Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus Prof. Kudret Özersay (see annex), which reflects the Turkish Cypriot views on the report of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights on the question of human rights in Cyprus (A/HRC/43/22), submitted to the Human Rights Council at its forty-third session. The Permanent Mission of the Republic of Turkey would appreciate it if the present note and the annex thereto* could be duly circulated as a document of the forty-third session of the Human Rights Council. * Reproduced as received, in the language of submission only. GE.20-08066(E) A/HRC/43/G/41 Annex to the note verbale dated 18 March 2020 from the Permanent Mission of Turkey to the United Nations Office at Geneva addressed to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights Letter dated 13 March 2020 of H. -

HASDER'le 30 YIL 30

YTL. - Price: 6 € (+Postage) Ederi: 10 HASDER'le 30 YIL 30 2007 YILLIĞI SAYI:55 2007, Yıl: 21, Sayı: 55 Sahibi Halk Sanatları Vakfı (HASDER) adına Ali NEBİH Aziz ENER Tuncer BAĞIŞKAN HASDER Arşivi Grafik-Baskı HASDER Dervişpaşa sokak No:17 Arabahmet Lefkoşa - Kıbrıs. Tel:(0392) 227 08 26 Fax: (0392) 228 77 98 Web site: www.hasder.org E-mail: [email protected] "Halkbilimi" nin bu sayısının yayınlanmasına katkıda bulunan BELÇA LTD.'e teşekkür ederiz Halkbilimi 1 İÇİNDEKİLER Okurlara ..........................................................................2 Siyasal Dönüşüm: Sarayönü’nden Ekran Önüne..........60 Ali NEBİH Gürdal HÜDAOĞLU Short Summary Of Contents...........................................3 Engin Anıl KTÖS ve Eğitim ...........................................................78 Şener ELCİL Eski Kıbrıs Gelenekleri üzerine Kutlu Adalı’nın kitabı “Dağarcık”tan alıntı - Sellain T’api Kuzey Kıbrıs’ta Nüfus Olgusu......................................80 Kutlu Adalı Muharrem FAİZ 20. Yüzyılın İlk Yarısındaki Gazetelere Göre Müzik Derlemeleri........................................................93 Kıbrıs Türk Toplumunun Ekonomik Durumu ................9 Selçuk GARANTİ Ahmet AN Garutsalı Ahmet Efendi ve Yorgancı Dalevera Usta....99 İnönü Köyünde Şehidalarla İlgili İnanışlar...................14 Eren BAŞARAN Çağın ZORT Kıbrıs’ta “Göz Dutması”na Dayalı İnanç ve Yetmiş Dört Sonrası Genelde Kültür Ve Özde Karpaz .19 Uygulamalar................................................................105 Özkan YIKICI Tuncer BAĞIŞKAN Masal derlemeleri -

The Origins of Greek Cypriot National Identity

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 12-1998 The Origins of Greek Cypriot National Identity Elena Koumna Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Koumna, Elena, "The Origins of Greek Cypriot National Identity" (1998). Master's Theses. 3888. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/3888 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ORIGINS OF GREEK CYPRIOT NATIONAL IDENTITY by Elena Koumna A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillmentof the requirements forthe Degree of Master of Arts Department of Political Science Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan December 1998 Copyrightby Elena Koumna 1998 To all those who never stop seeking more knowledge ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This thesis could have never been written without the support of several people. First, I would like to thank my chair and mentor, Dr. Jim Butterfield, who patiently guided me through this challenging process. Without his initial encouragement and guidance to pursue the arguments examined here, this thesis would not have materialized. He helped me clarify and organize my thoughts at a time when my own determination to examine Greek Cypriot identity was coupled with many obstacles. His continuing support and most enlightening feedbackduring the writing of the thesis allowed me to deal with the emotional and content issues that surfaced repeatedly. -

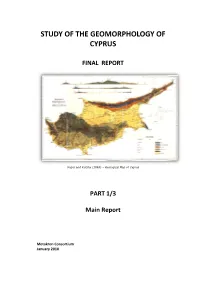

Study of the Geomorphology of Cyprus

STUDY OF THE GEOMORPHOLOGY OF CYPRUS FINAL REPORT Unger and Kotshy (1865) – Geological Map of Cyprus PART 1/3 Main Report Metakron Consortium January 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS PART 1/3 1 Introduction 1.1 Present Investigation 1-1 1.2 Previous Investigations 1-1 1.3 Project Approach and Scope of Work 1-15 1.4 Methodology 1-16 2 Physiographic Setting 2.1 Regions and Provinces 2-1 2.2 Ammochostos Region (Am) 2-3 2.3 Karpasia Region (Ka) 2-3 2.4 Keryneia Region (Ky) 2-4 2.5 Mesaoria Region (Me) 2-4 2.6 Troodos Region (Tr) 2-5 2.7 Pafos Region (Pa) 2-5 2.8 Lemesos Region (Le) 2-6 2.9 Larnaca Region (La) 2-6 3 Geological Framework 3.1 Introduction 3-1 3.2 Terranes 3-2 3.3 Stratigraphy 3-2 4 Environmental Setting 4.1 Paleoclimate 4-1 4.2 Hydrology 4-11 4.3 Discharge 4-30 5 Geomorphic Processes and Landforms 5.1 Introduction 5-1 6 Quaternary Geological Map Units 6.1 Introduction 6-1 6.2 Anthropogenic Units 6-4 6.3 Marine Units 6-6 6.4 Eolian Units 6-10 6.5 Fluvial Units 6-11 6.6 Gravitational Units 6-14 6.7 Mixed Units 6-15 6.8 Paludal Units 6-16 6.9 Residual Units 6-18 7. Geochronology 7.1 Outcomes and Results 7-1 7.2 Sidereal Methods 7-3 7.3 Isotopic Methods 7-3 7.4 Radiogenic Methods – Luminescence Geochronology 7-17 7.5 Chemical and Biological Methods 7-88 7.6 Geomorphic Methods 7-88 7.7 Correlational Methods 7-95 8 Quaternary History 8-1 9 Geoarchaeology 9.1 Introduction 9-1 9.2 Survey of Major Archaeological Sites 9-6 9.3 Landscapes of Major Archaeological Sites 9-10 10 Geomorphosites: Recognition and Legal Framework for their Protection 10.1 -

A Historical Perspective on Entrepreneurial Environment and Business-Government-Society Relationship in Cyprus

A Historical Perspective on Entrepreneurial Environment and Business-Government-Society Relationship in Cyprus Gizem ÖKSÜZOĞLU GÜVEN, PhD. Brunel Business School, Brunel University United Kingdom ABSTRACT This article studies the entrepreneurial environment and business-government-society relationship in Cyprus during the Ottoman Empire period (1571-1878) and during the British Colonial period (1878- 1960) with an emphasis on Cypriot Turks. These two periods have particular socio-cultural and economic importance in Cypriot history. Furthermore, these periods are significant in terms of setting out the basis of today’s entrepreneurial culture and practices in Cyprus. This article presents insights on the governance styles, significant figures and positions within society during those periods. It also discusses the connections between administrative officials and businesses. By doing so, it aims to shed light on the entrepreneurial environment in each of these periods. Extensive research of historical documents and relevant literature suggests quite similar structures in both periods, yet more complicated relationships during the British Colonial period. Keywords: Entrepreneurial environment, business-government-society relationship, Cyprus, business history, Ottoman Empire period, British colonial period, 1. Introduction This article aims to shed light on entrepreneurial practices and business-government-society relationship during two of the most recent and influential periods of Cyprus; the Ottoman Empire period and the British Colonial period. This article provides insights to current entrepreneurs and foreign investors to understand the antecedents of business culture, certain practices and structures that originate from those two periods in order to better adapt to the current entrepreneurial environment. The first section discusses each period, the way entrepreneurial practice and business-government- society relationship were shaped and the second section provides a discussion. -

Linguistic Practices in Cyprus and the Emergence of Cypriot Standard Greek*

San Diego Linguistic Papers 2 (2006) 1-24 LINGUISTIC PRACTICES IN CYPRUS AND THE EMERGENCE OF CYPRIOT STANDARD GREEK* Amalia Arvaniti University of California, San Diego ----------------------------------------------- In Cyprus today systematic changes affecting all levels of linguistic analysis are observed in the use of Standard Greek, giving rise to a distinct linguistic variety which can be called Cypriot Standard Greek. The changes can be attributed to the influence of English and Cypriot Greek (the local linguistic variety), and to the increasing use of the Standard in semi-formal occasions. Equally important is the reluctance to recognize the diglossic situation on the island (in which Standard Greek is the H variety and Cypriot Greek the L), for political and ideological reasons. This in turn means that the attention of the Cypriot speakers is not drawn to the differences between Standard Greek as spoken in Greece and their usage of it; thus the differences become gradually consolidated, while the users remain unaware of them. ----------------------------------------------- 1 Introduction The past two decades have seen a proliferation of scholarly work on the linguistic situation in Cyprus. This body of work is concerned with several topics, such as the speakers’ awareness of the linguistic varieties spoken on the island (e.g., Karyolemou & * This paper is a companion to Arvaniti (this volume b). Although the papers compliment each other, they are written in such a way that each can be read independently of the other; for this reason, some introductory sections (e.g. the historical background) show a degree of overlap. The bulk of the data in this article was gathered in Cyprus from 1996 to 2001, with additional data collected since then using a variety of web resources. -

Nitrogen and Phosphorus Fertilizing of Carrots

TECHNICAL BULLETIN 99 ISSN 0070-2315 NITROGEN AND PHOSPHORUS FERTILIZING OF CARROTS P.I. Orphanos and V. D. Krentos AGRICULTURAL RESEARCH INSTITUTE MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE AND NATURAL RESOURCES NITROGEN AND PHOSPHORUS FERTILIZING OF CARROTS P.I. Orphanos and V. D. Krentos SUMMARY Carrots have been an important export crop since the mid 1950s but the course of theindustly in production, price of the produce and exports has been rather enatic. The crop is sown in November and harvested in April through June. Before 1974 carrot growing was concentrated in the Argaki-Katokopia-Zodhia area. The eight experiments reported here were carried out in this area over the period 1968-71, and tested the combinations of four rates of N (0.63, 126. and 189 kgha) and four rates of P (0.23,46,and 69 kgiha). As a result of previous fertilizer P application. all experimental soils but one tested more than 8 ppm Olsen P. The test variety was Chantenay but in the last experiment Nantes was also included. In sir out of the eight experiments N increased yield significantly, and 63 to 1'26 kg Niha was required for maximum yield. By contrast only in one experiment in which the soil tested a mere 1 ppm Olsen P was yield increased by fertilizer P up to the rate of 46 kg Piha. The increase in yield due to N application was accompanied by a coincident increase in the percentage of exportable yield but at the highest N rate (189 kg Nha) percent exportable yield slightly declined. The dry matter content and the N,P and K contents of the roots were not influenced by either N or P fertilizing.