NYC School Segregation Report Card Still Last, Action Needed Now by Danielle Cohen, with a Foreword by Gary Orfield June 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

For Students on the Autism Spectrum

What YOU Can Do... A Message from Staten Island Borough President James P. Molinaro •Be well informed about your child and his or her needs. There are many resources in this guide that are available to help. Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) •Don’t wait if you have concerns. is the fastest-growing developmental Contact any of the agencies listed inside. disability in America today. While parents of children with ASD often learn early on what kind of treatment and •Know your child’s rights. services are needed, it can be difficult to gain access to them. It is crucial Reach out to your legislators and let them that effective services, treatment, and • education for children and adults with know how important services are for your ASD are accessed as quickly as possible. child or yourself. The earlier they receive appropriate services, the better the prognosis. Help raise autism awareness. • To help parents take action after their child has been The more we can educate our community, diagnosed with ASD, Staten Island’s autism services providers the easier it will be for our children. worked together to compile our Borough’s first-ever comprehensive resource guide to better support and inform local families and Find out where your elected officials stand on professionals. This handy booklet provides detailed contact • information for autism organizations on Staten Island that offer issues relating to autism. Don’t forget to VOTE. services to both children and adults. Finding the right place for autism treatment and services can be a difficult process, but we •Stay involved. -

Downloads.Php Enrollment Database)

UCLA K-12 Integration and Diversity Title NYC School Segregation Report Card: Still Last, Action Needed Now! Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5fx616qn Author Cohen, Danielle Publication Date 2021-06-10 Data Availability The data associated with this publication are available upon request. Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California NYC School Segregation Report Card Still Last, Action Needed Now By Danielle Cohen, with a foreword by Gary Orfield June 2021 Cover art by Taylor McGraw ©UCLA Civil Rights Project/Proyecto Derechos Civiles Table of Contents List of Figures ................................................................................................................................. ii List of Tables ................................................................................................................................. iii Foreword ......................................................................................................................................... 1 Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................ 9 Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 15 Harmful Effects of Segregation ................................................................................................ 16 History of Segregation in NYC Public Schools ........................................................................... -

CSI in the News

CSI in the News July 2012 csitoday.com/in-the-news Archive csitoday.com/publication/csi-in-the-news COLLEGE OF STATEN ISLAND The City University of New York Table of Contents Arts & Events . 3 Faculty & Staff . 6 Stories . 55 Students & Alumni . 85 Arts & Events Page 3 of 134 A Wider Spectrum By Stephen Greco 11 Jul 2012 When the New York Philharmonic plays its Concerts in the Parks, the entire city is invited. Stephen Greco reveals the inspirations and ambitions behind this long‐running cultural gift to New York City. Enjoying open‐air music with your neighbors is as old as civilization itself. New York leaders doubtless had this in mind back in the 19th century when, as part of a broader quality‐of‐life agenda, they endowed their growing metropolis with masses of magnificent public parks. These were places where culture and nature could come together, where urbanites could experience the richest kind of “cultural citizenship.” As such, the parks make a perfect setting for a New York cultural treasure that is, in fact, 15 years older than Central Park itself — the New York Philharmonic, which this July continues its tradition of playing free concerts throughout the boroughs of New York City. “I’ve always wanted the Orchestra to have a meaningful connection to the city,” says Philharmonic Music Director Alan Gilbert, a native New Yorker. “I want it to be a source of civic pride, to be a resource for the city, to be an obvious expression of what is great about the city.” Alan Gilbert and the New York Philharmonic in Central Park on July 14, This year’s return of the Philharmonic’s Concerts in the Parks 2009 features five free outdoor concerts, presented in some of the city’s photo by Chris Lee loveliest locales. -

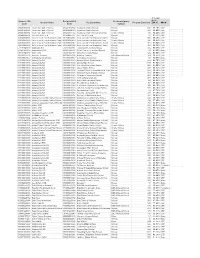

CEP May 1 Notification for USDA

40% and Sponsor LEA Recipient LEA Recipient Agency above Sponsor Name Recipient Name Program Enroll Cnt ISP % PROV Code Code Subtype 280201860934 Academy Charter School 280201860934 Academy Charter School School 435 61.15% CEP 280201860934 Academy Charter School 800000084303 Academy Charter School School 605 61.65% CEP 280201860934 Academy Charter School 280202861142 Academy Charter School-Uniondale Charter School 180 72.22% CEP 331400225751 Ach Tov V'Chesed 331400225751 Ach Tov V'Chesed School 91 90.11% CEP 333200860906 Achievement First Bushwick Charte 331300860902 Achievement First Endeavor Charter School 805 54.16% CEP 333200860906 Achievement First Bushwick Charte 800000086469 Achievement First University Prep Charter School 380 54.21% CEP 333200860906 Achievement First Bushwick Charte 332300860912 Achievement First Brownsville Charte Charter School 801 60.92% CEP 333200860906 Achievement First Bushwick Charte 333200860906 Achievement First Bushwick Charter School 393 62.34% CEP 570101040000 Addison CSD 570101040001 Tuscarora Elementary School School 455 46.37% CEP 410401060000 Adirondack CSD 410401060002 West Leyden Elementary School School 139 40.29% None 080101040000 Afton CSD 080101040002 Afton Elementary School School 545 41.65% CEP 332100227202 Ahi Ezer Yeshiva 332100227202 Ahi Ezer Yeshiva BJE Affiliated School 169 71.01% CEP 331500629812 Al Madrasa Al Islamiya 331500629812 Al Madrasa Al Islamiya School 140 68.57% None 010100010000 Albany City SD 010100010023 Albany School Of Humanities School 554 46.75% CEP 010100010000 Albany -

New York City FIRST Mega Celebration March 16 to 18, 2012 - Jacob K

New York City FIRST Mega Celebration March 16 to 18, 2012 - Jacob K. Javits Convention Center FIRST Robotics Competition Friday March 16-Sunday March 18 9:00 a.m.-5:00 p.m. FIRST Tech Challenge Championship Friday March 16-Saturday March 17 9:00 a.m.-5:00 p.m. FIRST LEGO League Championship Sunday March 18 9:30 a.m.-3:30 p.m. Junior FIRST LEGO League Expo Sunday March 18 9:30 a.m.-1:00 p.m. NYC FIRST Science and Technology College/Career Expo Friday March 16, Noon-4 p.m. Saturday, March 17, 11:00 a.m to 3:00 p.m. Sunday, March 18, 10:00 a.m to 3:00 p.m. All Photographs By Adriana M. Groisman/FIRST Welcome to the 12th Annual New York City FIRST Robotics Competition! The New York City FIRST (For the Inspiration and Recognition of Science and Technology) Robotics Competition proudly welcomes you to the 2012 New York City Regional mega celebration and competition here at the Jacob Javits Convention Center. Our mission is to inspire young people to be science and technology leaders by engaging them in exciting mentor-based programs that build science, engineering and technology skills that inspire innovation, cooperation, and gracious professionalism! FIRST Robotics has been going strong for over 20 years worldwide and we celebrate our 12th year in New York City. NYC FIRST programs engage thousands of elementary, intermediate and high school students as they build robots and compete on the playing field while actively using science and technology. -

Additional Ways to Graduate Quick Reference Guide

䄀搀搀椀琀椀漀渀愀氀 圀愀礀猀 吀漀 䜀爀愀搀甀愀琀攀 䠀椀最栀 匀挀栀漀漀氀 䐀椀瀀氀漀洀愀 ☀ 䔀焀甀椀瘀愀氀攀渀挀礀 倀爀漀最爀愀洀猀 ㈀ 㜀ⴀ㈀ 㠀 ADDITIONAL WAYS TO GRADUATE QUICK REFERENCE GUIDE YOUR OPTIONS: . Stay at your school. Depending on your age and school history (credit accumulation and Regents examinations) – staying in or returning to – your home school may be the best option for you. Enroll in a school or program that can help you get back on track to graduation. If staying in current school is not the best option, the schools and programs in this directory might be right for you. They include smaller classes, personalized learning environments, and connections to college and careers. General admissions criteria for schools and programs in this directory are listed below: TRANSFER SCHOOLS YOUNG ADULT BOROUGH CENTERS HIGH SCHOOL EQUIVALENCY . Ages 16-21 (varies by school) (YABCS) PROGRAMS . Must have completed one . Ages 17.5-21 . Ages 18-21 year of high school . Be in the fifth year of high . Attend a full-time or part-time . Number of credits required for school program entry varies by school but . Have, at least, 17 credits . Earn a high school equivalency could be as low as 0 credits . Part-time afternoon/evening diploma (formerly known as a . Full time, day school programs GED®) . Earn a high school diploma . Earn a high school diploma LEARNING TO WORK Many Transfer Schools and Young Adult Borough Centers are supported by the Learning to Work (LTW) initiative. LTW assists students overcome obstacles that impede their progress toward a high school diploma and leads them toward rewarding employment and educational experiences after graduation. -

Remote Option Ending, but Other Questions Remain

Conference: Securing A Win: Gray Fellows Movement Oct. 30, Live CSA Protects EA Transform Slow On In NYC Work, Salaries Schools School Safety 3 3 7 9 June 2021 Volume 56, Number 10 American Federation NEWS of School Administrators, COUNCIL OF SCHOOL SUPERVISORS AND ADMINISTRATORS AFL-CIO Local 1 Remote Option Family Leave Policy Ending, But Other One For All And Questions Remain All For Onesies ratitude continues to BY CHUCK WILBANKS has said all schools will be able to accom- pour in from members modate all students. CSA has already told Gwho’ve been able to On May 24, Mayor Bill de Blasio the mayor and the DOE that this isn’t the avail themselves of the family and Chancellor Meisha Ross Porter case, if current social distancing guide- leave benefit that CSA negoti- announced that there will be no remote lines remain in place. ated in 2020. learning option for the 2021-2022 school What would be the rules on school Anna Nelson, Assistant year, and, as a result, the COVID19- closures, were there to be another out- Principal, Bronx Latin School, based remote accommodations that were break? What of Covid testing of students said, “Luke (left, top) arrived granted to DOE employees this year will and staff? in March and I am really grate- officially sunset on June 30, 2021. Below is the letter Mr. Cannizzaro ful for the generous family The announcement came a week after sent to Mayor de Blasio. At press time, leave policy CSA negotiated. CSA President Mark Cannizzaro had sent CSA was continuing to press the DOE It’s allowed me to spend the the Mayor a letter urging him to provide to provide information on a range of time I needed with him. -

Extension Attached

F.; ATTACHED .r EXTENSION OMB No 1545-0047 Form 9 9 Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax Under section 501 (c), 527, or 4947(a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code (except black lung 2005 benefit trust or private foundation) Department of the Treasury Internal Revenue Service ► The organization may have to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements. A For the 2005 calendar year, or tax year beginning , and ending C Name of organization D Employer identification number B Check if applicable Please Address change use IRS The New York Communi ty Trust 13-3062214 label or Name change print or Number and street (or P 0 box if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/sui te E Telephone number type Initial return 909 Third Avenue 22nd Fl 212-686-0010 Specific City or town State or country ZIP + 4 F Accounting method : Cash []Accrual Final return Instruc- lions Amended return New York NY 10022-4752 (specify) ► Application pending • Section 501 (c)(3) organizations and 4947 (a)(1) nonexempt charitable H and I are not applicable to section 527 organizations trusts must attach a completed Schedule A (Form 990 or 990-EZ). H(a) Is this a group return for affiliates? q Yes No G Website : ► www.nycommunitytrust. org H(b) If 'Yes,' enter number of affiliates ► 2_ H(c) Are all affiliates included? Yes No J Organization type (check only one) ► E501 (c) ( 3 ) 4 (insert no) ^4947(a)(1) or 0527 (if 'No,* attach a list See instructions ) K Check here the organization's gross receipts are normally not more than $25,000 The H(d) Is this a separate return filed by an o an zatiion organization need not file a return with the IRS, but if the organization chooses to file a return, be covered by a group ruling? Yes a No sure to file a complete return Some states require a complete return . -

28Th Annual Book Awards Catalogue

Ezra Jack KE28th Annual Book AwardsAT Catalogue S Department of Education EZRA JACK KEATS AWARDS EXHIBITION SCHEDULE Central Branch of the Brooklyn Public Library 10 Grand Army Plaza Brooklyn, New York 11238 718. 230.1001 May 5 - May 23, 2014 Ezra Jack The New York City Department of Education gratefully acknowledges and thanks the Ezra Jack Keats Foundation and its Executive Director, Dr. Deborah Pope, for their generous sponsorship and support. KEATS 28th Annual Book Awards This catalogue was produced by the New York City Department of Education in collaboration with the Ezra Jack Keats Foundation. Front cover image: Aleksandra Stanisavljevic, In Praise of Plants: Part V, Stuyvesant High School, Manhattan Catalogue Back cover image: Joshue Socias, Tony Mapeke, The Dog who Saved the Day, PS 214X, The Lorraine Hansberry Academy, Bronx Editor: Kenneth Grebinar Original catalogue design by Pam Pollack Artwork photographed by Michael Ian No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microfilming, recording or otherwise without written permission from the publishers. Copyright 2014 New York City Department of Education All rights reserved Published 2014 Printed in the United States of America For information contact the Office of Arts and Special Projects, NYCDOE www.nyc.gov/schools/artseducation 4 The Annual Ezra Jack Keats Table of Contents Bookmaking Competition Elementary, middle and high schools throughout the LETTER FROM CARMEN FARIÑA ...........................................................................................................6 city enter this annual competition. Classes of students LETTER FROM DEBORAH POPE .............................................................................................................7 create books at their schools. A team at the school CITY-WIDE WINNER IN GRADES 3-5 determines which book is the school wide winner. -

Township Keas8ey Water Meters Fail to Register Usage

RARITAN MOST PROGRESSIVE TOWNSHIP WITH THE SUBURBAN NEWSPAPER LARGEST IN GUARANTEED THIS AREA RDS CIRCULATION Voice of the Raritan Bay District" VOL. III. — No. 46. FORDS AND RARITAN TOWNSHIP FRIDAY MORNING, JANUARY 13, 1939. PRICE THREE CENTS DEATHS RISE To Be Honored Heads New Group RARITAN TOWNSHIP.—Ac- KEAS8EY WATER BAILEY REPORTS cording to the annual report of TOWNSHIP BOARD V. B. Skov, registrar of vital statistics, submited Tuesday Rumoured METERS FAIL TO LARGE INCREASE night to Director of Public Safe- NAMES TWO TO ty Victor Pedersen, township deaths, including those of the As We Rocsevelt hospital and the New Likelt!.., REGISTER USAGE IN RABID CASES Jersey Home for Disabled. Vet- ESTIMATE GROUP erans, rose approximately twen- ALSO ADOPTS TEMPORARY Well, the second week of the new year is fast drawing 4 HOUSES HOOKED UP TO 1 31 PERSONS GIVEN PAS- ty per cent last year. The re- to a close ... No suits, no threats, no errors . We did METER-SEVERAL MET- TEUR TREATMENT DUR- port revealed 163 recorded BUDGET OF $39,990 ERS JUMPED ING 1938 deaths as compared with 130 for PENDING FINAL SETUP however, receive several letters giving us some very good 1937. Deaths exceeded the 146 tips for use here . That's what we like . The more, KEASBEY.—As a result of a pre WOODBRIDGE.—"Rabies have births for 1938. The records al- RARITAN TOWNSHIP. — The the better ... Of the communications received, we feel lirninary survey made toy Michael been unusually prevalent during so show that seventy marriage township board of commissioners, Korczowski, newly appointed sup- the past year." So stated Health licenses were issued. -

A Very Special Place African Story Network, Inc. the ALS Association

A Very Special Place African Story Network, Inc. The ALS Association Greater New York Chapter All-Islands Kiwanis Alpha Beta Foundation Alzheimer's Foundation of Staten Island Amazing Grace Interfaith Ministry Amazing Kids Connection (Amazing Grace Interfaith Ministry) Amethyst House American Cancer Society American Parkinson Disease Association (APDA) AMVETS - Post 917 Annabella Gonzalez Dance Theater Art Lab, Inc. Assistance Center for Deaf and Deafblind Children Autism Speaks Athukorala, Praveen Athukorala, Shavini Himansi Baltic Street AEH, Inc. Bartel, Jenna Angela Black, David Jr. Black, Michaela Bloomfield Conservancy Blue Lives Matter Borough President's Office Boy Scouts of America-Boy Scout Troop 76 Boy Scouts of America Post 2122 Explorers Bright Point Health Brighton Kiwanis Foundation Brotherhood for the Fallen, Inc. Busy Beach Day Care Center, Inc California Fire Foundation Calvary Chapel of Staten Island Camelot Family Foundation, Inc Cami, Alba Camp Good Grief of Staten Island Inc. Camp Kesem Stony Brook Cancer Tamer Foundation, LTD Carmel Richmond Nursing Home, Inc. Carl V. Bini Foundation Catholic School Region of Staten Island Chiari & Syringomyelia Foundation Children at Play Early Intervention Center Chong, Kimberly Christ Church New Brighton Christopher's Reason (The Resource Training Center, Inc.) Church of Holy Child Church of St. Andrew- Hemsley Community Hall Church of St. Clare Church of St. Roch City Access New York College of Staten Island College of Staten Island Foundation, Inc. Columcille Irish Cultural -

2020 Nyc 2020 High School Admissions

2020 NYC HIGH SCHOOL ADMISSIONS GUIDE 2020 NYC HIGH SCHOOL ADMISSIONS GUIDE MySchools.nyc Explore. Choose. Apply. Visit MySchools ( MySchools.nyc) to explore your high school options from your computer or phone, choose programs for your personalized application, and apply—all in one place. Year-round, you can use MySchools to: 0 Search an interactive high school directory for programs by name, location, accessibility, interest areas, academic off erings, activities, sports, and more! 0 Explore programs across the city. During the high school application period, you can also use MySchools to: 0 Access your personalized high school application—your school counselor will tell you how. 0 Save your favorite schools and programs. 0 Schedule your specialized high schools admissions test (SHSAT) or LaGuardia High School audition by early October. 0 Add 12 programs to your high school application. Place them in your order of preference, with your fi rst choice at the top as #1. 0 Apply by the deadline, December 2, 2019. Be sure to click the “Submit Application” button. We’re here to help! If you need support with MySchools or have questions about high school admissions: 0 Talk to your school counselor. 0 Call us at 718-935-2009. 0 Visit a Family Welcome Center—locations are listed on the inside back cover of this guide. ABOUT THE COVER Student: Nova Stanley | Teacher: Carl Landegger | Principal: Manuel Ureña Each year, the NYC Department of Education and Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum partner on a cover design challenge for public high school students. This book’s cover was designed by Nova Stanley, a student at High School of Art and Design.