Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Des Pas Sur La Neige

19TH CENTURY MUSIC Mystères limpides: Time and Transformation in Debussy’s Des pas sur la neige Debussy est mystérieux, mais il est clair. —Vladimir Jankélévitch STEVEN RINGS Introduction: Secrets and Mysteries sive religious orders). Mysteries, by contrast, are fundamentally unknowable: they are mys- Vladimir Jankélévitch begins his 1949 mono- teries for all, and for all time. Death is the graph Debussy et le mystère by drawing a dis- ultimate mystery, its essence inaccessible to tinction between the secret and the mystery. the living. Jankélévitch proposes other myster- Secrets, per Jankélévitch, are knowable, but ies as well, some of them idiosyncratic: the they are known only to some. For those not “in mysteries of destiny, anguish, pleasure, God, on the secret,” the barrier to knowledge can love, space, innocence, and—in various forms— take many forms: a secret might be enclosed in time. (The latter will be of particular interest a riddle or a puzzle; it might be hidden by acts in this article.) Unlike the exclusionary secret, of dissembling; or it may be accessible only to the mystery, shared and experienced by all of privileged initiates (Jankélévitch cites exclu- humanity, is an agent of “sympathie fraternelle et . commune humilité.”1 An abbreviated version of this article was presented as part of the University of Wisconsin-Madison music collo- 1Vladimir Jankélévitch, Debussy et le mystère (Neuchâtel: quium series in November 2007. I am grateful for the Baconnière, 1949), pp. 9–12 (quote, p. 10). See also his later comments I received on that occasion from students and revision and expansion of the book, Debussy et le mystère faculty. -

Debussy Préludes

Debussy Préludes Books I & II RALPH VOTAPEK ~ Debussy 24 Préludes Préludes, Book I (1909-1910) 37:13 1 I. Danseuses de Delphes (Lent et grave) 2:59 2 II. Voiles (Modéré) 3:09 3 III. Le vent dans la plaine (Animé) 2:07 4 IV. Les sons et les parfums tournent dans l’air du soir (Modéré) 3:10 5 V. Les collines d’Anacapri (Très modéré) 2:57 6 VI. Des pas sur la neige (Triste it lent) 3:47 7 VII. Ce qu’a vu le vent d’Ouest (Animé et tumultueux) 3:23 8 VIII. La fille aux cheveux de lin (Très calme et doucement expressif) 2:29 9 IX. La sérénade interrompue (Modérément animé) 2:28 10 X. La cathédrale engloutie (Profondément calme) 5:54 11 XI. La danse de Puck (Capricieux et léger) 2:40 12 XII. Minstrels (Modéré) 2:10 Préludes, Book II (1912-1913) 36:04 13 I. Brouillards (Modéré) 2:38 14 II. Feuilles mortes (Lent et mélancolique) 2:55 15 III. La Puerta del Vino (Mouvement de Habanera) 3:19 16 IV. Les Fées sont d’exquises danseuses (Rapide et léger) 2:56 17 V. Bruyères (Calme) 2:42 18 VI. Général Lavine — eccentric (Dans le style et le mouvement d’un Cakewalk) 2:28 19 VII. La terrasse des audiences du clair de lune (Lent) 3:59 20 VIII. Ondine (Scherzando) 3:08 21 IX. Hommage à Samuel Pickwick, Esq., P.P.M.P.C. (Grave) 2:25 22 X. Canope (Très calme et doucement triste) 2:53 23 XI. -

Liner Notes (PDF)

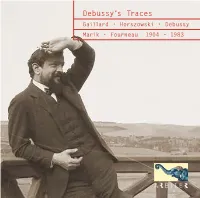

Debussy’s Traces Gaillard • Horszowski • Debussy Marik • Fourneau 1904 – 1983 Debussy’s Traces: Marius François Gaillard, CD II: Marik, Ranck, Horszowski, Garden, Debussy, Fourneau 1. Preludes, Book I: La Cathédrale engloutie 4:55 2. Preludes, Book I: Minstrels 1:57 CD I: 3. Preludes, Book II: La puerta del Vino 3:10 Marius-François Gaillard: 4. Preludes, Book II: Général Lavine 2:13 1. Valse Romantique 3:30 5. Preludes, Book II: Ondine 3:03 2. Arabesque no. 1 3:00 6. Preludes, Book II Homage à S. Pickwick, Esq. 2:39 3. Arabesque no. 2 2:34 7. Estampes: Pagodes 3:56 4. Ballade 5:20 8. Estampes: La soirée dans Grenade 4:49 5. Mazurka 2:52 Irén Marik: 6. Suite Bergamasque: Prélude 3:31 9. Preludes, Book I: Des pas sur la neige 3:10 7. Suite Bergamasque: Menuet 4:53 10. Preludes, Book II: Les fées sont d’exquises danseuses 8. Suite Bergamasque: Clair de lune 4:07 3:03 9. Pour le Piano: Prélude 3:47 Mieczysław Horszowski: Childrens Corner Suite: 10. Pour le Piano: Sarabande 5:08 11. Doctor Gradus ad Parnassum 2:48 11. Pour le Piano: Toccata 3:53 12. Jimbo’s lullaby 3:16 12. Masques 5:15 13 Serenade of the Doll 2:52 13. Estampes: Pagodes 3:49 14. The snow is dancing 3:01 14. Estampes: La soirée dans Grenade 3:53 15. The little Shepherd 2:16 15. Estampes: Jardins sous la pluie 3:27 16. Golliwog’s Cake walk 3:07 16. Images, Book I: Reflets dans l’eau 4:01 Mary Garden & Claude Debussy: Ariettes oubliées: 17. -

Orientalism As Represented in the Selected Piano Works by Claude Debussy

Chapter 4 ORIENTALISM AS REPRESENTED IN THE SELECTED PIANO WORKS BY CLAUDE DEBUSSY A prominent English scholar of French music, Roy Howat, claimed that, out of the many composers who were attracted by the Orient as subject matter, “Debussy is the one who made much of it his own language, even identity.”55 Debussy and Hahn, despite being in the same social circle, never pursued an amicable relationship.56 Even while keeping their distance, both composers were somewhat aware of the other’s career. Hahn, in a public statement from 1890, praised highly Debussy’s musical artistry in L'Apres- midi d'un faune.57 Debussy’s Exposure to Oriental Cultures Debussy’s first exposure to oriental art and philosophy began at Mallarmé’s Symbolist gatherings he frequented in 1887 upon his return to Paris from Rome.58 At the Universal Exposition of 1889, he had his first experience in the theater of Annam (Vietnam) and the Javanese Gamelan orchestra (Indonesia), which is said to be a catalyst 55Roy Howat, The Art of French Piano Music: Debussy, Ravel, Fauré, Chabrier (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2009), 110 56Gavoty, 142. 57Ibid., 146. 58François Lesure and Roy Howat. "Debussy, Claude." In Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online, http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/07353 (accessed April 4, 2011). 33 34 in his artistic direction. 59 In 1890, Debussy was acquainted with Edmond Bailly, esoteric and oriental scholar, who took part in publishing and selling some of Debussy’s music at his bookstore L’Art Indépendeant. 60 In 1902, Debussy met Louis Laloy, an ethnomusicologist and music critic who eventually became Debussy’s most trusted friend and encouraged his use of Oriental themes.61 After the Universal Exposition in 1889, Debussy had another opportunity to listen to a Gamelan orchestra 11 years later in 1900. -

Richard Goode, Piano

CAL PERFORMANCES PRESENTS PROGRAM Sunday, January 19, 2014, 3pm Claude Debussy (1862–1918) Préludes, Book I (1909–1910) Zellerbach Hall Danseuses de Delphes Voiles Le vent dans la plaine Richard Goode, piano Les sons et les parfums tournent dans l’air du soir Les collines d’Anacapri Des pas sur la neige Ce qu’a vu le vent d’Ouest PROGRAM La fille aux cheveux de lin La sérénade interrompue La Cathédrale engloutie La danse de Puck Leoš Janáček (1854–1928) From On an Overgrown Path (1901–1911) Minstrels Our Evenings A Blown-Away Leaf The program is subject to change. Come with Us! Good Night! Robert Schumann (1810–1856) Davidsbündlertänze, Op. 6 (1837) Lebhaft Innig Mit humor Ungeduldig Einfach Funded, in part, by the Koret Foundation, this performance is part of Cal Performances’ Sehr rasch 2013–2014 Koret Recital Series, which brings world-class artists to our community. Nicht schnell Frisch This concert is dedicated to the memory of Donald Glaser (1926–2013). Lebhaft Balladenmäßig — Sehr rasch Cal Performances’ 2013–2014 season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. Einfach Mit Humor Wild und lustig Zart und singend Frisch Mit gutem Humor Wie aus der Ferne Nicht schnell INTERMISSION 2 3 PROGRAM NOTES PROGRAM NOTES Leoš Janáček (1854–1928) birthday. “I would bind Jenůfa simply with the anguish”) and In Tears (“crying with a smile”). Linda Siegel described as vacillating between Selections from On an Overgrown Path black ribbon of the long illness, suffering and After On an Overgrown Path was published in “fits of depression with complete loss of reality laments of my daughter, Olga,” Janáček con- 1911, Janáček composed a second series of aph- and periods of seemingly placid adjustment to Composed in 1901–1902, 1908, and 1911. -

Debussy Préludes Children’S Corner Paavali Jumppanen

DEBUSSY PRÉLUDES CHILDREN’S CORNER PAAVALI JUMPPANEN 1 CLAUDE DEBUSSY (1862–1918) CD 1 Préludes I 1 I. Danseuses de Delphes 3:46 2 II. Voiles 3:50 3 III. Le vent dans la plaine 2:15 4 IV. « Les sons et les parfums tournent dans l’air du soir » 4:37 5 V. Les collines d’Anacapri 3:29 6 VI. Des pas sur la neige 4:16 7 VII. Ce qu’a vu le vent d’Ouest 3:40 8 VIII. La fille aux cheveux de lin 2:59 9 IX. La sérénade interrompue 2:42 10 X. La cathédrale engloutie 7:15 11 XI. La danse de Puck 2:50 12 XII. Minstrels 2:32 44:11 2 CD 2 Préludes II 1 I. Brouillards 3:17 2 II. Feuilles mortes 3:42 3 III. La puerta del Vino 3:26 4 IV. « Les fées sont d’exquises danseuses » 3:14 5 V. Bruyères 3:24 6 VI. « General Lavine » – eccentric – 2:35 7 VII. La terrasse des audiences du clair de lune 5:23 8 VIII. Ondine 3:37 9 IX. Hommage à S. Pickwick Esq. P.P.M.P.C. 2:37 10 X. Canope 3:50 11 XI. Les tierces alternées 2:32 12 XII. Feux d’artifice 4:49 Children’s Corner 13 I. Doctor Gradus ad Parnassum 2:20 14 II. Jimbo’s Lullaby 3:50 15 III. Serenade for the Doll 2:41 16 IV. The snow is dancing 2:48 17 V. The little Shepherd 3:31 18 VI. Golliwogg’s cake walk 3:02 60:38 PAAVALI JUMPPANEN, piano 3 CLAUDE DEBUSSY 4 Debussy’s Musical Imagery “I try to create something different–in a sense realities–and these imbeciles call it Impressionism” Claude Debussy Claude Debussy (1862–1918) cherished enigmatic statements and left behind conflicting remarks about the issue of musical imagery: on the one hand, he thought it was “more important to see a sunrise than to hear the Pastoral Symphony,” while on the other hand, as he wrote in a letter to the composer Edgar Varèse, he “liked images as much as music.” Debussy’s nuanced relationship with the worldly inspirations of his music links him with the artistic movement known as Symbolism. -

CRPH106 URBANA 66 Oec410e.105 EMS PRICE MF $O,45 HC...$11,60 340P

N080....630 ERIC REPORT RESUME ED 013 040 9..02..66 24 (REV) THE THEORY OFEXPECATION APPLIEDTO MUSICAL COLWELL, RICHARD LISTENING GFF2I3O1 UNIVERSITYOF ILLINOIS, CRPH106 URBANA 66 OEC410e.105 EMS PRICE MF $O,45 HC...$11,60 340P. *MUSIC EDUCATION, *MUSIC TECHNIQUES,*LISTENING SKILLS, *TEACHING METHODS,FIFTH GRADES LISTENING, SURVEYS, ILLINFrLS,URSAMA THE PROJECT PURPOSES WERE TO IDENTIFY THEELEMENTS IN MUSICUSED BY EXPERT LISTENERS INDETERMINING THE ARTISTIC DISCOVER WHAT VALUE OF MUSICS TO MUSICAL SKILLS ANDKNOWLEDGES ARE NECESSARY/ LISTENER TO RECOGNIZE FOR THE THESE ELEMENTS, ANDTO USE THESE CMIPARiSON WITH A FINDINGS IN A SPECIFIC AESTHETICTHEORY. ATTEMPTSWERE PACE TO DETERMINE WHETHERTHESE VALUE ELEMENTSARE TEACHABLE, LEVELS AT WHICH IF SOS THE AGE THEY ARE TEACHABLE,THE CREATION OF EVALUATE RECOGNITION MEASUREMEN7S TO OF THESE ELEMENTS,AND THE SKILLS AND KNOWLEDGES USED* THE TWO PROBLEMSSTUDIED WERE (1) THE KNOWLEDGES A STUDENT SKIMAS AND WOULD NEED TO PARTICIPATEIN THE MUSICAL EXPERIENCE AS DESCRIBEDBY MEYER S THEORY WHETHER THESE OF EXPECTATIONAND (2) PROBLEMS COULD BETAUGHT WITHIN A 2 FIFTH GRADE CHILDREN* YEAR PERIOD TO THE TOTAL LIST OFSKILLS AND KNOWLEDGES (APPROPRIATE FORMUSICAL LISTENINGAND GATHERED FROM EXPERTS) WAS OBVIOUSLY THE MUSICAL MUCH TOO EXTENSIVEAND DIFFICULT TOUTILIZE IN A ONE YEARGRADE SCHOOLCOURSE. TWENTY SEVEN WERE USED IN FIF=TH GRADE CLASSES INTERPRETING THERESULTS OF THE STUDYAND DRAW FROM THEM*APPROXIMATELY 10 PERCENTOP THE TESTSMEW THESE CLASSESWERE HIGHLYCOMMENDABLE, WITH MELODIES, CONTRASTING CADENCES, PHASESS PARTS, TIMBRE, ANDCI IMAXES ALLCORRECTLY IDENTIFIED AND MARKED.TWO VIEWPOINTS RESULTED FROM THESTUDV...(1) DESIRABILITY OF ANEARO,Y START ININTENSIVE MUSICAL THE IMPRACTICABILII"E LEARNING AND (2) OF TEACHING ADEQUATEMUSICAL SKILLS AND KNOWLEDGES WITHINTHE EXISTING ELEMENTARY MUSICFRAMEWORK BECAUSE OF LIMITED TIME ALLOWED,(GC) U. -

La Cathédrale Engloutie from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

La cathédrale engloutie From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia La cathédrale engloutie (The Sunken Cathedral) is a prelude written by the French composer Claude Debussy for solo piano. It was published in 1910 as the tenth prelude in Debussy’s first of two volumes of twelve piano preludes each. It is characteristic of Debussy in its form, harmony, and content. The "organ chords" feature parallel harmony. Contents 1 Musical impressionism 2 Legend of Ys 3 Musical analysis 3.1 Form 3.2 Thematic/motivic structure 3.3 Context 3.4 Parallelism 4 Secondary Parameters 5 Arrangements 6 Notes 7 External links Musical impressionism This prelude is an example of Debussy's musical impressionism in that it is a musical depiction, or allusion, of an image or idea. Debussy quite often named his pieces with the exact image that he was composing about, like La Mer, Des pas sur la neige, or Jardins sous la pluie. In the case of the two volumes of preludes, he places the title of the piece at the end of the piece, either to allow the pianist to respond intuitively and individually to the music before finding out what Debussy intended the music to sound like, or to apply more ambiguity to the music's allusion. [1] Because this piece is based on a legend, it can be considered program music. Legend of Ys This piece is based on an ancient Breton myth in which a cathedral, submerged underwater off the coast of the Island of Ys, rises up from the sea on clear mornings when the water is transparent. -

The Consecutive-Semitone Constraint on Scalar Structure: a Link Between Impressionism and Jazz1

The Consecutive-Semitone Constraint on Scalar Structure: A Link Between Impressionism and Jazz1 Dmitri Tymoczko The diatonic scale, considered as a subset of the twelve chromatic pitch classes, possesses some remarkable mathematical properties. It is, for example, a "deep scale," containing each of the six diatonic intervals a unique number of times; it represents a "maximally even" division of the octave into seven nearly-equal parts; it is capable of participating in a "maximally smooth" cycle of transpositions that differ only by the shift of a single pitch by a single semitone; and it has "Myhill's property," in the sense that every distinct two-note diatonic interval (e.g., a third) comes in exactly two distinct chromatic varieties (e.g., major and minor). Many theorists have used these properties to describe and even explain the role of the diatonic scale in traditional tonal music.2 Tonal music, however, is not exclusively diatonic, and the two nondiatonic minor scales possess none of the properties mentioned above. Thus, to the extent that we emphasize the mathematical uniqueness of the diatonic scale, we must downplay the musical significance of the other scales, for example by treating the melodic and harmonic minor scales merely as modifications of the natural minor. The difficulty is compounded when we consider the music of the late-nineteenth and twentieth centuries, in which composers expanded their musical vocabularies to include new scales (for instance, the whole-tone and the octatonic) which again shared few of the diatonic scale's interesting characteristics. This suggests that many of the features *I would like to thank David Lewin, John Thow, and Robert Wason for their assistance in preparing this article. -

THESIS for the Degree of MASTER of MUSIC by Mary Nan Hudgins, B. Mus. January, 1956

AX)a A DESCRIPTIVE ANALYSIS OF THE PRELUDES (BOOK I) OF CLAUDE DEBUSSY THESIS Presented. to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC By Mary Nan Hudgins, B. Mus. Denton, Texas January, 1956 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS . ....... ... iv Chapter I. HISTORY OF THEPRELUDE. .......... II. THE PRELUDES (BOOK I) OF DEBUSSY . 18 III. CONCLUSION. ... ... ...... .. 59 BIBLIOGRAPHY. 62 iii LIST OF ILLUST RAT IONS Figure Page 1. "Prelude," from the Ileboroh Tablature. 3 2. "Organ Prelude," from the Buxheim gan Book. 5 3. Intonazione by Andrea Gabrieli. 8 4. "Praeludium," Number 1, from The CopL. Works of Louis Couperin. 11 5. Measures 1-4 of Danseuses deDelhes. 24 6. Measures 4-5 of Danseuses deDelhes. 25 7. Measures 27-28 of Danseuses de 2Eheas. 25 8. Measures 1-2?of Voiles. 26 9. Measures 5-9 of Voiles. 27 10. Measures 23-24 of Voiles. 28 11. Measures 1-2 of Le Vent dans la plaine. 29 12. a) Measures 9-10, b) Measures 30-31 of Le Vent dans la plane . 30 13. Measures 38-39 of Te Vent dans 1,.plaine. 31 14. Measures 57-59 of Le Vent dans Ia plaine. 32 15. Measures 52-53 of Les sons et les parfums tournent dans 1'air du soir. 34 16. Measures 1-2 of Les collines d'Ana ri . 35 17. Measures 14-15 of Les collines d'Anacapri . 36 18. Measures 31-35 of Les collines d'Anacapri* 37 19. -

Programs Built on a Concept Programs That Include Newer Repertoire Conventional Programs with a Twist

Sample Solo Recital Programs of Classical Pianists Compiled by the Music Entrepreneurship & Career Center, Updated March 2016 We offer these programs, organized in the following three categories, to help rising pianists develop innovative programs of their own: Programs Built on a Concept Programs that Include Newer Repertoire Conventional Programs with a Twist Programs Built on a Concept Lara Downes The Story of a Steinway The Piano is Born Ludwig van Beethoven: "Hammerklavier" Sonata The Piano Soars Frédéric Chopin: Nocturne Op. 23 #1 The Piano Roars Sergei Prokofiev: Toccata Op. 11 The Piano Swings George Gershwin: I Got Rhythm The Piano Sings from The Billie Holiday Songbook, arr. Jed Distler The Piano Today Nico Muhly: Running Shao-Hsun Chang Govans Presbyterian Church, Baltimore; May 5, 2013 Feathered Friends: Great Composers Celebrate Birdsong Jean-Philippe Rameau Le rappel des oiseaux (Bird Calls) Jean-Philippe Rameau La poule (The Hen) Ludwig van Beethoven Sonata No. 25 in G Major, Op. 79, “Cuckoo” Franz Liszt from Deux Légendes, S. 175: -No. 1: La predication aux oiseaux (Sermon to the Birds) Olivier Messiaen Vingt regards sur l'enfant-Jésus -No. 8: Regard des Hauteurs (Contemplation of the Heights) Jenny Q Chai Spectrum NYC, New York City; May 7, 2013 Acqua Alta (High Water): A Program about Global Warming Domenico Scarlatti Sonatas György Kurtág Hommage à Domenico Scarlatti Orlando Gibbons Italian Ground (1613) Marco Stroppa Ninnananna from Miniature Estrose Claude Debussy Prelude: La cathédrale engloutie Maurice Ravel Une barque sur l’océan from Miroirs Franz Liszt La lugubre gondola Nils Vigeland I Turisti* Milica Paranosic Bubble* Michael Vincent Waller Acqua Santa* John Cage Water Walk * pieces written for Jenny Chai Sample Piano Programs, p. -

Parting the Veils of Debussy's Voiles Scottish Music Review

Parting the Veils of Debussy’s Voiles David Code Lecturer in Music, University of Glasgow Scottish Music Review Abstract Restricted to whole-tone and pentatonic scales, Debussy’s second piano prelude, Voiles, often serves merely to exemplify both his early modernist musical language and his musical ‘Impressionism’. Rejecting both arid theoretical schemes and vague painterly visions, this article reconsiders the piece as an outgrowth of the particular Mallarméan lessons first instantiated years earlier in the Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune. In developing a conjecture by Renato di Benedetto, and taking Mallarmé’s dance criticism as stimulus to interpretation, the analysis makes distinctive use of video-recorded performance to trace the piece’s choreography of hands and fingers on the keyboard’s music-historical stage. A contribution by example to recent debates about the promises and pitfalls of performative or ‘drastic’ analysis (to use the term Carolyn Abbate adopted from Vladimir Jankélévitch), the article ultimately adumbrates, against the background of writings by Dukas and Laloy, a new sense of Debussy’s pianistic engagement with the pressing questions of his moment in the history of modernism. I will try to glimpse, through musical works, the multiple movements that gave birth to them, as well as all that they contain of the inner life: is that not rather more interesting than the game that consists of taking them apart like curious watches? -Claude Debussy1 Clichés and Questions A favourite of the anthologies and survey texts, Debussy’s second piano prelude, Voiles (‘sails’ or ‘veils’), has attained near-iconic status as the most characteristic single exemplar of his style.