ECCC, Case 002/01, Issue 20

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A History of the Anlong Veng Community a History Of

A HIstoRy Of Anlong Veng CommunIty A wedding in Anlong Veng in the early 1990s. (Cover photo) Aer Vietnamese forces entered Cambodia in 1979, many Khmer Rouge forces scaered to the jungles, mountains, and border areas. Mountain 1003 was a prominent Khmer Rouge military base located within the Dangrek Mountains along the Cambodian-Thai border, not far from Anlong Veng. From this military base, the Khmer Rouge re-organized and prepared for the long struggle against Vietnamese and the People’s Republic of Kampuchea government forces. Eventually, it was from this base, Khmer Rouge forces would re-conquer and sele Anlong Veng in early 1990 (and a number of other locations) until their re-integration into Cambodian society in late 1998. In many ways, life in Anlong Veng was as difficult and dangerous as it was in Mountain 1003. As one of the KR strongholds, Anlong Veng served as one of the key launching points for Khmer Rouge guerrilla operations in Cambodia, and it was subject to constant aacks by Cambodian government forces. Despite the perilous circumstances and harsh environment, the people who lived in Anlong Veng endeavored, whenever possible, to re-connect with and maintain their rich cultural heritage. Tossed from the seat of power in 1979, the Khmer Rouge were unable to sustain their rigid ideo- logical policies, particularly as it related to community and family life. During the Democratic Movement of the Khmer Rouge Final Stronghold Kampuchea regime, 1975–79, the Khmer Rouge prohibited the traditional Cambodian wedding ceremony. Weddings were arranged by Khmer Rouge leaders and cadre, who oen required mass ceremonies, with lile regard for tradition or individual distinction. -

Promoting Sustainable Agriculture in Samroung Commune, Prey Chhor District, Kampong Cham Province Through Network of RCE Greater Phnom Penh

Promoting Sustainable Agriculture in Samroung Commune, Prey Chhor District, Kampong Cham Province through Network of RCE Greater Phnom Penh Saruom RAN Cambodia Branch, Institute of Environment Rehabilitation and Conservation, Phnom Penh, Cambodia Email: [email protected] Kanako KOBAYASHI Extension Center, Institute of Environment Rehabilitation and Conservation, Tokyo, Japan Lalita SIRIWATTANANON Rajamangala University of Technology Thanyaburi, Pathum Thani, Thailand / Southeast Asia Office, Institute of Environment Rehabilitation and Conservation, Pathum Thani, Thailand Machito MIHARA Institute of Environment Rehabilitation and Conservation, Tokyo, Japan / Faculty of Regional Environment Science, Tokyo University of Agriculture, Tokyo, Japan Bunthan NGO Royal University of Agriculture, Phnom Penh, Cambodia / Institute of Environment Rehabilitation and Conservation, Tokyo, Japan Abstract: Agriculture is one of the important sectors in Cambodia, as more than 70 percent of populations are engaging in the agricultural sector. Phnom Penh is the capital of Cambodia having more than 1.3 million people. RCE Greater Phnom Penh (RCE GPP) was established in December 2009 to promote ESD in Cambodia. RCE Greater Phnom Penh covers not only Phnom Penh but also surrounding provinces, such as Kampong Cham, Kampong Chhnang, Kampong Speu, Kandal, Prey Veng and Takeo. Recently, in Kampong Cham province of Cambodia, subsistence agriculture tends to be converted to mono-culture. Also, more that 60 percent of farmers have been applying agricultural chemicals without understanding the impact on health and food safety. It is necessary to promote and enhance the understanding of sustainable agriculture among local people including farmers and elementary school students, as the students are the successors of local farmers. So, attention has been paid to Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) in the agricultural sector for achieving food safety, conserving environment and reducing expense for agricultural chemicals in Kampong Cham province. -

Social Safeguards Due Diligence Report (Kampong Cham)

Social Safeguards Due Diligence Report Project No. 50099 May 2018 CAM: Fourth Greater Mekong Subregion Corridor Towns Development Kampong Cham CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. KAMPONG CHAM SUBPROJECT DESCRIPTION AND COMPONENTS 1 III. OBJECTIVE OF DUE DILIGENCE AND METHODOLGY 3 A. Objective and Scope of Due Diligence 3 B. Methodology 4 IV. PROPOSED PROJECT IMPLEMENTATION ARRANGEMENTS 4 V. PHYSICAL WORKS 5 VI. DUE DILIGENCE FINDINGS 7 A. Land Acquisition and Impact Screening 7 B. Temporary Disturbance 11 C. Consultations 11 VII. GRIEVANCE REDRESS MECHANISM 11 VIII. VII.CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATION 12 APPENDIXES 1. Kampong Cham WWTP and Landfill Land Certificates 2. List of Persons Met and Photos FIGURES Figure 1 Location Map of the Participating Town Figure 2 Proposed Combined Sewer Service Area and Location of Wastewater Treatment Plant in Kampong Cham Figure 3 Location of the Proposed Kampong Cham Controlled Landfill Figure 4 Conceptual Layout of the Kampong Cham Wastewater Treatment Plant Figure 5 Conceptual Layout of the Proposed Kampong Cham Controlled Landfill Figure 6 Location map of the proposed Boeng Bassac Lagoon Figure 7 Photos of WWTP Site and the Pump House Figure 8 Photos of the Proposed Controlled Landfill Site in Kampong Cham I. INTRODUCTION 1. The Fourth Greater Mekong Subregion Corridor Towns Development Project (GMS- CTDP-4 or Project) will support the Governments of Cambodia and the Lao People’s Democratic Republic in enhancing the competitiveness of selected towns located along the Central Mekong Economic Corridor in the Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS). It is aligned with the Government of Cambodia’s Rectangular Strategy for national development. -

First Quarterly Report: January-March, 2012

mCÄmNÐlÉkßrkm<úCa Documentation Center of Cambodia Quarterly Report: January‐March, 2012 DC‐Cam Team Leaders and the Management Team Prepared and Compiled by Farina So Office Manager Edited by Norman (Sambath) Pentelovitch April, 2012 Sirik Savina, Outreach Coordinator, discusses with the villagers about the hearing process at Khmer Rouge Tribunal. Abbreviations CHRAC Cambodian Human Rights Action Committee CP Civil Party CTM Cambodia Tribunal Monitor DC‐Cam Documentation Center of Cambodia DK Democratic Kampuchea ECCC Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia ICC International Criminal Court ITP Sida Advanced International Training Programme KID Khmer Institute for Democracy KR Khmer Rouge MMMF Margaret McNamara Memorial Fund MRDC Mondul Kiri Resource and Documentation Centre OCP Office of Co‐Prosecutors OCIJ Office of Co‐Investigating Judges PTSD Post‐Traumatic Stress Disorder Sida Swedish International Development Agency TSL Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum UN United Nations UNDP United Nation for Development Program USAID United States Agency for International Development VOT Victims of Torture VPA Victims Participation Project VSS Victim Support Section YFP Youth for Peace YRDP Youth Resource Development Program 2 Table of Contents Executive Summary.............................................................................................................. 1 Results/Outcome................................................................................................................. 7 Raised Public Awareness on the Value of Documents............................................. -

The Khmer Rouge Tribunal: an Ambiguous Good News Story

perspectives The Khmer Rouge Tribunal: An Ambiguous Good News Story Milton Osborne A u g u s t 2 0 0 7 The Lowy Institute for International Policy is an independent international policy think tank based in Sydney, Australia. Its mandate ranges across all the dimensions of international policy debate in Australia – economic, political and strategic – and it is not limited to a particular geographic region. Its two core tasks are to: • produce distinctive research and fresh policy options for Australia’s international policy and to contribute to the wider international debate. • promote discussion of Australia’s role in the world by providing an accessible and high quality forum for discussion of Australian international relations through debates, seminars, lectures, dialogues and conferences. Lowy Institute Perspectives are occasional papers and speeches on international events and policy. The views expressed in this paper are the author’s own and not those of the Lowy Institute for International Policy. The Khmer Rouge Tribunal: an ambiguous good news story Milton Osborne It’s [the Khmer Rouge Tribunal] heavily symbolic and won’t have much to do with justice . It will produce verdicts which delineate the KR leadership as having been a small group and nothing to do with the present regime. Philip Short, author of Pol Pot: anatomy of a nightmare, London, 2004, quoted in Phnom Penh Post, 26 January8 February 2007. Some ten months after it was finally inaugurated in July 2006, and more than twentyeight years after the overthrow of the Democratic Kampuchean (DK) regime led by Pol Pot, the Extraordinary Chambers of the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC), more familiarly known as the Khmer Rouge Tribunal, has at last handed down its first indictment. -

Ung Choeun, Known As Ta

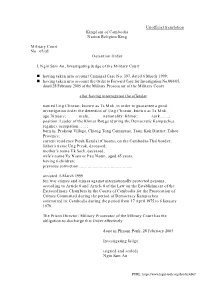

Unofficial translation Kingdom of Cambodia Nation Religion King Military Court No 07/05 Detention Order I, Ngin Sam An, Investigating Judge of the Military Court n having taken into account Criminal Case No. 397, dated 6 March 1999; n having taken into account the Order to Forward Case for Investigation No.004/05, dated 28 February 2005 of the Military Prosecutor of the Military Court after having interrogated the offender named Ung Choeun, known as Ta Mok, in order to guarantee a good investigation order the detention of Ung Choeun, known as Ta Mok, age 78 years; male; nationality: Khmer; rank…….; position: Leader of the Khmer Rouge (during the Democratic Kampuchea regime); occupation……; born in Prakeap Village, Chieng Tong Commune, Tram Kok District, Takeo Province; current residence Pteah Kandal (Choam), on the Cambodia-Thai border; father’s name Ung Preak, deceased; mother’s name Uk Soch, deceased; wife’s name Vy Naen or Pau Naem, aged 45 years; having 6 children; previous conviction:………………………………… arrested: 6 March 1999 for: war crimes and crimes against internationally protected persons, according to Article 6 and Article 8 of the Law on the Establishment of the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia for the Prosecution of Crimes Committed during the period of Democracy Kampuchea committed in: Cambodia during the period from 17 April 1975 to 6 January 1979. The Prison Director/Military Prosecutor of the Military Court has the obligation to discharge this Order effectively done in Phnom Penh, 28 February 2005 Investigating -

KRT TRIAL MONITOR Case 002 ! Issue No

KRT TRIAL MONITOR Case 002 ! Issue No. 32 ! Hearing on Evidence Week 27 ! 13-16 August 2012 Case of Nuon Chea, Khieu Samphan and Ieng Sary Asian International Justice Initiative (AIJI), a project of East-West Center and UC Berkeley War Crimes Studies Center …Let me apologize to the Cambodians who lost their children or parents. What I am saying here is the truth. And I personally lost some of my relatives, aunts and uncles. And for those brothers in their capacity as leaders, they also lost relatives and family members. - Witness Suong Sikoeun I. OVERVIEW* After the suspension of Monday’s hearing caused by Ieng Sary’s poor health, trial resumed on Tuesday with the conclusion of the testimony of Mr. Ong Thong Hoeung, an intellectual who returned to Cambodia during DK and found himself performing manual labor in re- education camps to “refashion” himself. Next, the Chamber called Mr. Suong Sikoeun, the director of information and propaganda of the Minister of Foreign Affairs (MFA), to resume his testimony. Suong Sikoeun expounded on the MFA, FUNK and GRUNK, and Pol Pot’s role in DK. Giving due consideration to his frail health, the Trial Chamber limited his examination to half-day sessions. To manage the time efficiently, reserve witness Ms. Sa Siek (TCW-609), a cadre who worked at the Ministry of Propaganda during the regime, commenced her testimony. Sa Siek focused on the evacuation of Phnom Penh, the structure of the Ministry of Propaganda, and DK radio broadcasts. Procedural issues arose during the hearing on Wednesday, when the Trial Chamber issued unclear rulings on the introduction of documents to witnesses. -

1 St Quarterly

Searching for the truth. Magazine of the Documentation Center of Cambodia Special English Edition, First Quarter 2004 Table of Contents EDITORIALS Denials and Genocide Education .................................1 Letters from Youk Chhang: Son Sen Two Important New Projects at DC-Cam ...................2 A Reply to Comrade Nuon Chea .................................5 DOCUMENTATION Tau Thy Pheak, Director of Office K-15 ...................6 Chou Chet, alias Sy, Western Zone Secretary ...........8 To Respected Office 870 (Telegram) .......................11 DC-Cam’s 2004 Work Plan .....................................12 Public Information Room ....................................23 Building the Case against Senior KR Leaders ........25 HISTORY The Cham Rebellion ...............................................26 Second “Open Letter” of Khieu Samphan ..............27 This is not Karma! ...................................................31 The Story of Prak Yoeun .........................................34 Khieu Samphan Mat Ly and His Struggle for the Cham Community....35 Live for the Children ..............................................37 Copyright © LEGAL Documentation Center of Cambodia 50 Legal Precedents in Yugoslav Court .......................39 All rights reserved. 50 50 PUBLIC DEBATE Licensed by the Ministry of Information of 50 Political Transition and Justice ................................43 the Royal Government of Cambodia, 100 Khieu Samphan ......................................................51 Prakas No.0291 P.M99, 100 Letter: -

List of Interviewees

mCÄmNÐlÉkßrkm<úCa DOCUMENTATION CENTER OF CAMBODIA Phnom Penh, Cambodia LIST OF POTENTIAL INFORMANTS FROM MAPPING PROJECT 1995-2003 Banteay Meanchey: No. Name of informant Sex Age Address Year 1 Nut Vinh nut vij Male 61 Banteay Meanchey province, Mongkol Borei district 1997 2 Ol Vus Gul vus Male 40 Banteay Meanchey province, Mongkol Borei district 1997 3 Um Phorn G‘¿u Pn Male 50 Banteay Meanchey province, Mongkol Borei district 1997 4 Tol Phorn tul Pn ? 53 Banteay Meanchey province, Mongkol Borei district 1997 5 Khuon Say XYn say Male 58 Banteay Meanchey province, Mongkol Borei district 1997 6 Sroep Thlang Rswb føag Male 60 Banteay Meanchey province, Mongkol Borei district 1997 7 Kung Loeu Kg; elO Male ? Banteay Meanchey province, Phnom Srok district 1998 8 Chhum Ruom QuM rYm Male ? Banteay Meanchey province, Phnom Srok district 1998 9 Than fn Female ? Banteay Meanchey province, Phnom Srok district 1998 Documentation Center of Cambodia Searching for the Truth EsVgrkKrBit edIm, IK rcg©M nig yutþiFm‘’ DC-Cam 66 Preah Sihanouk Blvd. P.O.Box 1110 Phnom Penh Cambodia Tel: (855-23) 211-875 Fax: (855-23) 210-358 [email protected] www.dccam.org 10 Tann Minh tan; mij Male ? Banteay Meanchey province, Phnom Srok district 1998 11 Tatt Chhoeum tat; eQOm Male ? Banteay Meanchey province, Phnom Srok district 1998 12 Tum Soeun TMu esOn Male 45 Banteay Meanchey province, Preah Net Preah district 1997 13 Thlang Thong føag fug Male 49 Banteay Meanchey province, Preah Net Preah district 1997 14 San Mean san man Male 68 Banteay Meanchey province, -

Cambodia's Dirty Dozen

HUMAN RIGHTS CAMBODIA’S DIRTY DOZEN A Long History of Rights Abuses by Hun Sen’s Generals WATCH Cambodia’s Dirty Dozen A Long History of Rights Abuses by Hun Sen’s Generals Copyright © 2018 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-36222 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org JUNE 2018 ISBN: 978-1-6231-36222 Cambodia’s Dirty Dozen A Long History of Rights Abuses by Hun Sen’s Generals Map of Cambodia ............................................................................................................... 7 Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Khmer Rouge-era Abuses ......................................................................................................... -

Confidential Introductory Submission

INTRODUCTION 1. We, the Co-Prosecutors of the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC): (1) Having considered the Law on the Establishment of the ECCC; (2) Having considered the Internal Rules of the ECCC; (3) Having seen the Criminal Case File No. 004 dated 15 November 2008; and (4) Having conducted a preliminary investigation submit the following: 2. Beginning in early 1977, T A An led a group of cadre from the Southwest Zone who purged and replaced the existing cadre of the Central (old North) Zone. As a result of this purge, T A An became the Deputy Secretary of the Central Zone and the Secretary of Sector 41. Prior to leading the Central Zone purge, T A An had been a Member of the Sector 35 Standing Committee in the Southwest Zone and an elected representative RIWKH3HRSOH¶V5HSUHVHQWDWLYH$VVHPEO\ 3. In 1977 and 1978, another group of Southwest Zone cadre led by Ta Mok and T A Tith purged and replaced the existing cadre of the Northwest Zone. As a result of this purge, T A Tith became the Acting Secretary of the Northwest Zone and Secretary of Sector 1. Prior to leading the Northwest Zone purge, T A Tith had been the Secretary of the Kirivong District of the Southwest Zone in 1976 and 1977. 4. In June 1977, as part of the broader Northwest Zone purge led by Ta Mok and T A Tith, I M Chaem led a purge of Preah Net Preah District of Sector 5 of the Northwest Zone and became the Secretary of Preah Net Preah District. -

Conflicting Sites of Memory in Post-Genocide Cambodia

Brigitte Sion Conflicting Sites of Memory in Post-Genocide Cambodia A new road connects the towns of Siem Reap to Along Veng, in northern Cambodia; it now takes less then two hours from the temples of Angkor to reach the last bastion of the Khmer Rouge, in what used to be a dense jungle. It is enough time for my driver, thirty-one-year-old Vann, to tell me the story of his family. ‘‘Every Cambodian family has lost relatives under the Khmer Rouge,’’ he says. Vann’s mother lost her husband and children in the early years of Pol Pot’s murderous regime. She remarried and gave birth to a new set of children, including Vann. ‘‘A total of ten family members died,’’ he sums up. Later, when Vann was in school, he was required, along with all residents of his village outside Siem Reap, to excavate the killing fields and exhume the bodily remains for cremation. ‘‘The smell was horrible,’’ he recalls. ‘‘I see too many bones. It scares me.’’ For years, Vann avoided the former mass graves. ‘‘My children don’t know what happened.’’ A Khmer song is playing in the car. ‘‘Old music from the 1960s,’’ he says by means of introduction. ‘‘The singer was killed.’’ We pass Along Veng and continue through the lush countryside and rice fields toward the Thai border. It takes a number of stops and questions, and a few dollars, to find the cremation site of Pol Pot, who was burned hastily in 1998 on a pile of rubbish. It is hidden behind a house, amid high weeds, junk, and garbage.