Lltest.Vp (Read Only)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Raya Dunayevskaya Papers

THE RAYA DUNAYEVSKAYA COLLECTION Marxist-Humanism: Its Origins and Development in America 1941 - 1969 2 1/2 linear feet Accession Number 363 L.C. Number ________ The papers of Raya Dunayevskaya were placed in the Archives of Labor History and Urban Affairs in J u l y of 1969 by Raya Dunayevskaya and were opened for research in May 1970. Raya Dunayevskaya has devoted her l i f e to the Marxist movement, and has devel- oped a revolutionary body of ideas: the theory of state-capitalism; and the continuity and dis-continuity of the Hegelian dialectic in Marx's global con- cept of philosophy and revolution. Born in Russia, she was Secretary to Leon Trotsky in exile in Mexico in 1937- 38, during the period of the Moscow Trials and the Dewey Commission of Inquiry into the charges made against Trotsky in those Trials. She broke politically with Trotsky in 1939, at the outset of World War II, in opposition to his defense of the Russian state, and began a comprehensive study of the i n i t i a l three Five-Year Plans, which led to her analysis that Russia is a state-capitalist society. She was co-founder of the political "State-Capitalist" Tendency within the Trotskyist movement in the 1940's, which was known as Johnson-Forest. Her translation into English of "Teaching of Economics in the Soviet Union" from Pod Znamenem Marxizma, together with her commentary, "A New Revision of Marxian Economics", appeared in the American Economic Review in 1944, and touched off an international debate among theoreticians. -

The Theory of the Cuban Revolution

THE RISING NEGRO STRUGGLE New Weapons in Freedom Now Arsenal By George Breitman ment. Unemployed struggles are nothing new in our year. By direct action and by mass action, they sought DETROIT — Every genuine mass movement, like history, nor are demonstrations and picket lines. But this to stop construction in order to gain serious attention every revolution, produces new things — new relation was an unemployed struggle under the banner of racial to their demands (jobs, admission to the building trade ships, new ways of looking at life, new methods, new equality, and that combination gave it a unique char unions, end of discrimination in the apprentice pro institutions — or new ways of doing old things. This acter and a new dimension. grams) . article concerns recent developments testifying to the As a young man, I was active in the unemployed I hold that this was something new; that it is an im profoundly creative and radical character of the Negro movements of the big depression in the Thirties. We portant addition to the weapons of struggle in the movement for equality. staged marches on Washington, we once occupied the arsenal of the unemployed; and that it w ill be adopted I am not dealing here with new methods and ideas seats of the state legislators in m y native state fo r ten and adapted to their own needs by the big unemployed introduced between 1960 and 1962, about which much days, we picketed City Hall, staged sitdowns in the wel movement or movements of white as well as black already has been written, such as the sit-ins, filling of fare offices, struck and shut down WPA projects, etc. -

Claude Mckay's a Long Way from Home

Through a Black Traveler's Eyes: Claude McKay's A Long Way from Home Tuire Valkeakari Yale University Abstract: This essay analyzes Jamaican-born Claude McKay's discussion of racism(s) and nationalism(~) in his travelogue/autobiography A Long Way from Home ( 1937), in which he chronicles his sojourn in Europe and North Africa and addresses his complex relationship to the United States. Much of McKay's social analysis draws, as this essay establishes, on his observation that racism and nationalism tend to be intertwined and feed 011 each othe1: While describing his travels, McKay presents himselfas a bordercrosser who is "a bad nationalist" and an "internationalist" - a cosmopolitan whose home cannot be defined by any fixed national labels or by nationalist or racialist identity politics. This essay's dialogue with McKay's memoir ultimately reconstructs his difficult and of1-frustrated quest for democracy - the political condition that Ralph Ellison once eloquently equated with "man~· being at home in. the world." Key words: Claude McKay - nationalism - transnationalism - cosmopolitanism - race - racism - travel The way home we seek is that condition of man's being at home in the world, which is called love, and which we tenn democracy. - Ralph Elli son, "Brave Words for a Startling Occasion" I said I was born in the West Indies and lived in the United States and that I was an American, even though I was a British subject, but 1 preferred to think of myself as an internationalist. The chaoL1Sh said he didn't understand what was an internationalist. J laughed and said that an internationalist was a bad nationalist. -

Sylvia Pankhurst's Sedition of 1920

“Upheld by Force” Sylvia Pankhurst’s Sedition of 1920 Edward Crouse Undergraduate Thesis Department of History Columbia University April 4, 2018 Seminar Advisor: Elizabeth Blackmar Second Reader: Susan Pedersen With dim lights and tangled circumstance they tried to shape their thought and deed in noble agreement; but after all, to common eyes their struggles seemed mere inconsistency and formlessness; for these later-born Theresas were helped by no coherent social faith and order which could perform the function of knowledge for the ardently willing soul. Their ardor alternated between a vague ideal and the common yearning of womanhood; so that the one was disapproved as extravagance, and the other condemned as a lapse. – George Eliot, Middlemarch, 1872 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................... 2 Abbreviations ............................................................................................................................ 3 Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 4 The End of Edwardian England: Pankhurst’s Political Development ................................. 12 After the War: Pankhurst’s Collisions with Communism and the State .............................. 21 Appealing Sedition: Performativity of Communism and Suffrage ....................................... 33 Prison and Release: Attempted Constructions of Martyrology -

Bio-Bibliographical Sketch of George Breitman

Lubitz' TrotskyanaNet George Breitman Bio-Bibliographical Sketch Contents: • Basic biographical data • Biographical sketch • Selective bibliography • Sidelines, notes on archives Basic biographical data Name: George Breitman Other names (by-names, pseud. etc.): Alberts ; G.B. ; Philip Blake ; Drake ; Chester Hofla ; Anthony Massini ; Albert Parker ; John F. Petrone ; Sloan ; G. Sloane Date and place of birth: February 28, 1916, Newark, NJ (USA) Date and place of death: April 19, 1986, New York, NY (USA) Nationality: USA Occupations, careers, etc.: Writer, editor, printer, historian, party organizer, political leader Time of activity in Trotskyist movement: 1935 - 1986 (lifelong Trotskyist) Biographical sketch Note: This biographical sketch is primarily based on A tribute to George Breitman : writer, organizer, revolutionary / ed. by Naomi Allen and Sarah Lovell, New York, NY, 1987 (containing obituaries, reminiscences and appraisals of G. Breitman by some 50 individuals and some 14 organizations) and on other items listed below under the heading Selective bibliography: books and articles about Breitman. George Breitman was born on February 28, 1916 at Newark, New Jersey, as son of Benjamin Breit man, an iceman, and his wife Pauline (b. Trattler), a houseworker. George Breitman grew up in a Ne wark working class neighbourhood together with his brother Samuel and his elder sister Celia, who soon joined the ranks of the Young Communist League (YCL), the Communist Party’s youth organiza tion, and who had a strong influence on George. He began to read voraciously, one of his favourite hangouts being the Newark Public Library. In 1932, in midst the Great Depression, he graduated from Newark Central High School and like most of his classmates had to join the ranks of the unemployed youth. -

~ Marxism and the Negro Struggle

~ Marxism and The Negro struggle Harold Cruse George Breitman Clifton DeBerry Merit Publishers 873 Broadway New York, N. Y. 10003 First printing March, 1965 Second printing June, 1968 Printed in the United States of America ns Harold Cruse's two-part article, "Marxism and the Negro," appeared in the May and June 1964 issues of the monthly magazine Liberator and is reprinted here with its permission. A one-year subscription to Liberator costs $3 and may be ordered from Liberator, 244 East 46th Street, New York, N. Y. 10017. George Breitman's five-part series, "Marxism and the Negro Struggle," appeared during August and September 1964 in the weekly newspaper The Militant and is reprinted here with its permission. A one-year subscription to The Militant costs $3 and may be ordered from The Militant, 873 Broadway, New York, N. Y. 10003. Clifton DeBerry's article, "A Reply to Harold Cruse," is reprinted from the October 1964 issue of Liberator. Contents MARXISM AND THE NEGRO By Harold Cruse Part I 5 Part 11 11 MARXISM AND THE NEGRO STRUGGLE By George Breitman What Marxism Is and How It Develops 17 The Colonial Revolution in Today's World 23 The Role of the White Workers 29 The Need and Result of Independence 34 Relations Between White and Black Radicals 40 A REPLY TO HAROLD CRUSE By Clifton DeBerry 45 Marxism and the Negro By HAROLD CRUSE Part I When the Socialist Workers highest level of organizational Party (Trotskyist) announced in the scope and programmatic independ- New York Times, January 14, that ence in this century . -

D. H. Lawrence and the Harlem Renaissance

‘You are white – yet a part of me’: D. H. Lawrence and the Harlem Renaissance A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2019 Laura E. Ryan School of Arts, Languages and Cultures 2 Contents Abstract ...................................................................................................................... 3 Declaration ................................................................................................................. 4 Copyright statement ................................................................................................... 5 Acknowledgements .................................................................................................... 6 Introduction ................................................................................................................ 7 Chapter 1: ‘[G]roping for a way out’: Claude McKay ................................................ 55 Chapter 2: Chaos in Short Fiction: Langston Hughes ............................................ 116 Chapter 3: The Broken Circle: Jean Toomer .......................................................... 171 Chapter 4: ‘Becoming [the superwoman] you are’: Zora Neale Hurston................. 223 Conclusion ............................................................................................................. 267 Bibliography ........................................................................................................... 271 Word Count: 79940 3 -

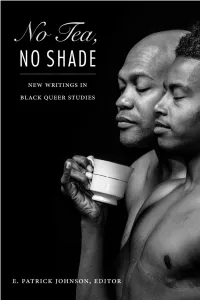

NO TEA, NO SHADE This Page Intentionally Left Blank No Tea, NO SHADE

NO TEA, NO SHADE This page intentionally left blank No Tea, NO SHADE New Writings in Black Queer Studies EDITED BY E. Patrick Johnson duke university press Durham & London 2016 © 2016 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of Amer i ca on acid- free paper ∞ Typeset in Adobe Caslon by Westchester Publishing Services Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Johnson, E. Patrick, [date] editor. Title: No tea, no shade : new writings in Black queer studies / edited by E. Patrick Johnson. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: lccn 2016022047 (print) lccn 2016023801 (ebook) isbn 9780822362227 (hardcover : alk. paper) isbn 9780822362425 (pbk. : alk. paper) isbn 9780822373711 (e- book) Subjects: lcsh: African American gays. | Gay and lesbian studies. | African Americans in popu lar culture. | Gays in popu lar culture. | Gender identity— Political aspects. | Sex in popu lar culture. Classification: lcc e185.625.n59 2016 (print) | lcc e185.625 (ebook) | ddc 306.76/608996073— dc23 lc rec ord available at https:// lccn . loc . gov / 2016022047 Cover art: Philip P. Thomas, Sharing Tea, 2016. © Philip P. Thomas. FOR ALL THE QUEER FOREMOTHERS AND FOREFATHERS This page intentionally left blank CONTENTS foreword Cathy J. Cohen xi acknowl edgments xv introduction E. Patrick Johnson 1 CHAPTER 1. Black/Queer Rhizomatics Train Up a Child in the Way Ze Should Grow . JAFARI S. ALLEN 27 CHAPTER 2. The Whiter the Bread, the Quicker You’re Dead Spectacular Absence and Post-Racialized Blackness in (White) Queer Theory ALISON REED 48 CHAPTER 3. Troubling the Waters Mobilizing a Trans* Analytic KAI M. -

One Million Copies

Page Four ’HE DAILY WORKER Workers (Communist) Party HARVESTER SHOP W. f>. ELECTION ‘ BULLETIN TELLS CAMPAIGN TOURS WORKERS PARTY ENTERS HERE’S ONE CASE! VATU IKE- UmS CONDUCTED "One fellow-worker In my shop said to me: "Well, maybe you guys WORKERS' NEEDS C. E. Ruthenberg i YO&C WORKEQS LEA6UE CANDIDATES IN STATE are all right for the time when there’ll be a revolution here like in General Secretary of the Workers (Communist) Russia. But there ain’t any revolution now—so what have you got to Third Edition Is Full of Party, is starting off his ELECTIONS THIS YEAR say. I guess nothing.’’ big election campaign tour with a Full Speed Ahead to Open National Youth "I showed him I gave Meaty Information meeting at Buffalo on October 14. The soon he was wrong. him a copy of the CON- * s'" In a number of states nominations have meeting will be held been filed by petition while In othere the GRESSIONAL PROGRAM OF THE PARTY proved to that at Workers' Hall, School End of October petition and him we campaion ia still in progress to By MARTIN ABERN. 36 AVest Huron street. Comrade Ruth- • ! place have something to say about every question that la of Interest to Workers (Communist) Party can- the enberg will speak Work- didates officially on ballots. The third issue of the Harvester on: “What a last day of October see the long-awaited opening of the workers. He read It and then the next day he said that he for The will the NA- Nominations officially filed: was us Bulletin, Issued by McCormick ers’ and Farmers’ Government Will and was going to vote us and try get the TIONAL TRAINING SCHOOL of the YOUNG WORKERS COMMUNIST for to others to vote for us. -

UCLA HISTORICAL JOURNAL Vol

''Cocktail Picket Party" The Hollywood Citizen—News Strike, The Newspaper Guild, and the Popularization of the "Democratic Front" in Los Angeles Michael Furmanovsky The ten-week strike of Hollywood Citizen-News editorial workers in the spring and summer of 1938 left an indelible mark on the history of Los Angeles labor. Almost unmatched in the city's history for the large size and glamorous composition of its picket lines, the strike's transformation into a local "cause celebre" owed much to the input of the Communist Party of Los Angeles (CPLA) and its widely diffused allies. While the Communists were not responsible for calling the walkout in May 1938, the subsequent development of the strike into a small-scale symbol of the potential inherent in liberal-labor-left unity was largely attributable to the CPLA's carefully planned strategy, which attempted to fulfill the goals set by the American Communist Party during the "Democratic Front" period (1938-39); namely, to mobilize the broadest possible network of pro- Roosevelt groups and individuals, integrated with the full complement of Party-led organizations. These would range during the Citizen-News strike from CIO unions and liberal assemblymen, to fellow-travelling Holly- wood celebrities and Communist affiliated anti-fascist organizations.' The Hollywood Citizen-News strike was far from an unqualified success either for the strikers or for the broader political movement envisaged by the Communist Party in 1938-39, nevertheless it became a rallying point for those on the Communist and non-Communist left who looked to the New Deal and the CIO as the twin vehicles for a real political transforma- tion and realignment in the United States. -

Some Important CEC Decisions

Some Important CEC Decisions Published in Official Bulletin of the Communist Party of America (Section of the Communist International [New York], no. 2 (circa Aug. 15, 1921), pp. 1-2. Some of the miscellaneous decisions of the Central Executive Committee during the past two months [June and July 1921] are as follows: Sub-committees have been elected to investigate and report on the question of participation in the coming elections, on the Irish question, on the Negro question. These sub-committees are now at work. Transfers to Russia. Until further notice no membership certificates will be issued for Soviet Russia, except in special cases (such as party couriers). Ex-Soldiers Organizations. Members are encouraged to join Ex-Soldiers organizations, par- ticularly those composed of privates, and to form nuclei within for conducting our propaganda. The formation of such nuclei should be reported through Party channels. Harry Wicks. The recommendation of an investigating committee that Harry Wicks shall not be admitted to the Party was approved. The informa- tion proves him to be absolutely undesirable within the Party ranks. International Delegates. Baldwin [Oscar Tyverovsky] was elected to represent the Ameri- can section on the Executive Committee of the CI. Marshall [Max Bedacht] has instructions to return immediately after the adjourn- ment of the Third Congress [June 22-July 12, 1921]. The others are to return after the conclusion of the Congress of the Red Trade Union International [July 3-19, 1921]. 1 CEC Organization. The Central Executive Committee has organized itself as follows: Executive Secretary ............. Carr [L.E. Kattterfeld] Assistant Secretary ............. -

PLANS ARE COMPLETED for ‘DAILY’ PICNIC in QUEENS SUNDAY Call Stresses Clta!L N S

Page Two LY Y ORKER. NEW YORK. FRIDAY. AUGUST 1934 PLANS ARE COMPLETED FOR ‘DAILY’ PICNIC IN QUEENS SUNDAY Call Stresses CLta!l N S. 14,000 at Sacco-Vanzetti Memorial L D Workers Urged Political A alue !J .f'|U. OfßigTurnout Pledge to Free Herndon and 9 Boys In Madison Sq. To Emulate Germans Districts Depend On Stormy Ovation Given THOUSANDS GREET HERNDON AT BRONX COLISEUM RALLY Demonstration on Dock In Thaelmann Outings for Funds Hero—Hathaway Is Tomorrow to Prepare Drive Principal Speaker for Youth Day Meet in Press Drive Many Signatures Already Collected in Committee's Bv CYRIL BRIGGS y. NEW YORK. Plans which c. L. CALLS NEW YORK.—In grim ; Campaign for Million Names in the splendid good time commem- NEW YORK.—The Young Com- guaranteed a oration of the legal murder of Sacco to the thousands who attend the j munist League yesterday issued a Demand for Leader’s Release and Vanzetti seven years ago, and young and Daily Worker picnic Sunday have revolutionary call to all workers a determination that j against all been completed, the Picnic Angelo Herndon and the Scott.?boro students to demonstrate NEW YORK.—Lauding the cour- the freedom of Thaelmann but will I war and fascism on International Committee announced yesterday. boys shall not suffer the same fate, ageous action of tens of thousands also be a help in the fight for the j Youth Day, Sept. 1. the day when Urging all mass organizations to 14,000 persons in a spirited demon- | of German workers who braved liberation of the writers, Ludwig,.